The Geotagging Counterpublic: the Case of Facebook Remote Check-Ins to Standing Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Analysis and Action Plan on a Social Media Strategy for Disaster Response: Risk Mitigation

__________________________ A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS AND ACTION PLAN ON A SOCIAL MEDIA STRATEGY FOR DISASTER RESPONSE: RISK MITIGATION Prepared by summer 2017 Masters students at the University of Southern California’s Sol Price School of Public Policy for Italy’s Dipartimento Protezione Civile. __________________________ Acknowledgments This report was written and compiled by Wenjing Dong, Maria de la Luz Garcia, Kalisi Kupu, Leyao Li, Hilary Olson, Xuepan Zeng, and Giovanni Zuniga. We want to thank Dr. Eric Heikkila, Ph.D., for his insight and supervision during this process. We would also like to thank Professors Veronica Vecchi and Raffaella Saporito from the SDA Bocconi School of Management for their coordination efforts and use of their facilities, as well as providing us with educational enrichment and guidance while in Milan, Italy. A final thanks to the Dipartimento Protezione Civile for being available to us and for answering all of our many questions. The Dipartimento Protezione Civile’s support and feedback were greatly appreciated and instrumental in the creation of this report. 1. Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATIONS ............................................................................. 3 CONSIDERATION 1. A PERSON-CENTRIC APPROACH .................................................. 3 CONSIDERATION 2. VULNERABLE SUBGROUPS ........................................................... 4 CONSIDERATION 3. DATA NEEDS ..................................................................................... 5 II. MOVING -

A Study of the Diffusion of Innovations and Hurricane Response Communication in the U.S

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Communication & Theatre Arts Theses Communication & Theatre Arts Summer 2019 A Study of the Diffusion of Innovations and Hurricane Response Communication in the U.S. Coast Guard Melissa L. Leake Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_etds Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Military and Veterans Studies Commons Recommended Citation Leake, Melissa L.. "A Study of the Diffusion of Innovations and Hurricane Response Communication in the U.S. Coast Guard" (2019). Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, Communication & Theatre Arts, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/cqhe-xy91 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_etds/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication & Theatre Arts at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication & Theatre Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS AND HURRICANE-RESPONSE COMMUNICATION IN THE U. S. COAST GUARD by Melissa L. Leake B.A. May 2018, Pennsylvania State University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS LIFESPAN & DIGITAL COMMUNICATION OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2019 Approved by: Thomas Socha (Director) Brenden O’Hallarn (Member) Katherine Hawkins (Member) ABSTRACT A STUDY OF THE DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS AND HURRICANE-RESPONSE COMMUNICATION IN THE U. S. COAST GUARD Melissa L. Leake Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. Thomas Socha Hurricane Harvey (HH) is considered to be the first natural disaster where social-network applications to request help surpassed already overloaded 911 systems (Seetharaman & Wells, 2017). -

Geotagging: an Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision

Geotagging: An Innovative Tool To Enhance Transparency and Supervision Transparency through Geotagging Noel Sta. Ines Geotagging Geotagging • Process of assigning a geographical reference, i.e, geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) + elevation - to an object. • This could be done by taking photos, nodes and tracks with recorded GPS coordinates. • This allows geo-tagged object or SP data to be easily and accurately located on a map. WhatThe is Use Geotagging and Implementation application in of the Geo Philippines?-Tagging • A revolutionary and inexpensive approach of using ICT + GPS applications for accurate visualization of sub-projects • Device required is only a GPS enabled android cellphone, and access to freely available apps • Easily replicable for mainstreaming to Government institutions & CSOs • Will help answer the question: Is the right activity implemented in the right place? – (asset verification tool) Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geotagging Example No. 1: Visualization of a farm-to-market road in a conflict area: showing specific location, ground distance, track / alignment, elevation profile, ground photos (with coordinates, date and time taken) of Farm-to-market Road, i.e. baseline information + Progress photos + 3D visualization Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geotagging Example No. 2: Location and Visualization of rehabilitation of a city road in Earthquake damaged-area in Tagbilaran, Bohol, Philippines by the auditors and the citizen volunteers Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geo-tagging Example No. 3 Visualization of a water supply project showing specific location, elevation profile from the source , distribution lines and faucets, and ground photos of community faucets Geotagging: An Innovative Tool to Enhance Transparency and Supervision Geo-tagging Example No. -

IEEE 2015 Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC)

Using Open-source Hardware to Support Disadvantaged Communications Andrew Weinert, Hongyi Hu, Chad Spensky, and Benjamin Bullough MIT Lincoln Laboratory 244 Wood Street Lexington, MA 02420-9108 {andrew.weinert,hongyi.hu,chad.spensky,ben.bullough}@ll.mit.edu Abstract—During a disaster, conventional communications have transformed response [2]. However, there is frequently infrastructures are often compromised, which prevents local a disconnect between the realities the information systems populations from contacting family, friends, and colleagues. The at the affected location and those in the ubiquitous cloud. lack of communication also impedes responder efforts to gather, Internet enabled web technologies such as crowdsourcing [3] organize, and disseminate information. This problem is made and social media [4] have helped facilitate interaction across worse by the unique cost and operational constraints typically these actors, but fail when communications at the affected associated with the humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) space. In response, we present a low-cost, scalable system region are either degraded or nonexistent due to either natural that creates a wide-area, best-effort, ad-hoc wireless network for or human actions. For example, an estimated three million emergency information. The Communication Assistance Technol- people were without cellular service immediately following ogy over Ad-Hoc Networks (CATAN) system embraces the maker the Haiti Earthquake (2010) [5]. Similarly, cellphone networks and do it yourself (DIY) communities by leveraging open-source were overwhelmed in the moments after the 2013 Boston and hobbyist technologies to create cheap, lightweight, battery- Marathon bombings [6]. This effectively disconnects the peo- powered nodes that can be deployed quickly for a variety of ple in the affected region from the rest of the world (e.g., their operations. -

Geotagging Photos to Share Field Trips with the World During the Past Few

Geotagging photos to share field trips with the world During the past few years, numerous new online tools for collaboration and community building have emerged, providing web-users with a tremendous capability to connect with and share a variety of resources. Coupled with this new technology is the ability to ‘geo-tag’ photos, i.e. give a digital photo a unique spatial location anywhere on the surface of the earth. More precisely geo-tagging is the process of adding geo-spatial identification or ‘metadata’ to various media such as websites, RSS feeds, or images. This data usually consists of latitude and longitude coordinates, though it can also include altitude and place names as well. Therefore adding geo-tags to photographs means adding details as to where as well as when they were taken. Geo-tagging didn’t really used to be an easy thing to do, but now even adding GPS data to Google Earth is fairly straightforward. The basics Creating geo-tagged images is quite straightforward and there are various types of software or websites that will help you ‘tag’ the photos (this is discussed later in the article). In essence, all you need to do is select a photo or group of photos, choose the "Place on map" command (or similar). Most programs will then prompt for an address or postcode. Alternatively a GPS device can be used to store ‘way points’ which represent coordinates of where images were taken. Some of the newest phones (Nokia N96 and i- Phone for instance) have automatic geo-tagging capabilities. These devices automatically add latitude and longitude metadata to the existing EXIF file which is already holds information about the picture such as camera, date, aperture settings etc. -

Geotag Propagation in Social Networks Based on User Trust Model

1 Geotag Propagation in Social Networks Based on User Trust Model Ivan Ivanov, Peter Vajda, Jong-Seok Lee, Lutz Goldmann, Touradj Ebrahimi Multimedia Signal Processing Group Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Motivation 2 We introduce users in our system for geotagging in order to simulate a real social network GPS coordinates to derive geographical annotation, which are not available for the majority of web images and photos A GPS sensor in a camera provides only the location of the photographer instead of that of the captured landmark Sometimes GPS and Wi-Fi geotagging determine wrong location due to noise http: //www.pl acecas t.net Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Motivation 3 Tag – short textual annotation (free-form keyword)usedto) used to describe photo in order to provide meaningful information about it User-provided tags may sometimes be spam annotations given on purpose or wrong tags given by mistake User can be “an algorithm” http://code.google.com/p/spamcloud http://www.flickr.com/photos/scriptingnews/2229171225 Multimedia Signal Processing Group Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Goal 4 Consider user trust information derived from users’ tagging behavior for the tag propagation Build up an automatic tag propagation system in order to: Decrease the anno ta tion time, and Increase the accuracy of the system http://www.costadevault.com/blog/2010/03/listening-to-strangers Multimedia -

UC Berkeley International Conference on Giscience Short Paper Proceedings

UC Berkeley International Conference on GIScience Short Paper Proceedings Title Tweet Geolocation Error Estimation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0wf6w9p9 Journal International Conference on GIScience Short Paper Proceedings, 1(1) Authors Holbrook, Erik Kaur, Gupreet Bond, Jared et al. Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.21433/B3110wf6w9p9 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California GIScience 2016 Short Paper Proceedings Tweet Geolocation Error Estimation E. Holbrook1, G. Kaur1, J. Bond1, J. Imbriani1, C. E. Grant1, and E. O. Nsoesie2 1University of Oklahoma, School of Computer Science Email: {erik; cgrant; gkaur; jared.t.bond-1; joshimbriani}@ou.edu 2University of Washington, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Email: [email protected] Abstract Tweet location is important for researchers who study real-time human activity. However, few studies have examined the reliability of social media user-supplied location and description in- formation, and most who do use highly disparate measurements of accuracy. We examined the accuracy of predicting Tweet origin locations based on these features, and found an average ac- curacy of 1941 km. We created a machine learning regressor to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the textual content of these fields, and obtained an average accuracy of 256 km. In a dataset of 325788 tweets over eight days, we obtained city-level accuracy for approximately 29% of users based only on their location field. We describe a new method of measuring location accuracy. 1. Introduction With the rise of micro-blogging services and publicly available social media posts, the problem of location identification has become increasingly important. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

Asia-Pacific Issue Paper on Social Media

___________________________________________________________________________ 2017/TEL56/DSG/009 Agenda Item: 3.2.2 Asia-Pacific Issue Paper on Social Media Purpose: Information Submitted by: ISOC ICT Development Steering Group Meeting Bangkok, Thailand 14 December 2017 Issue Paper: Asia-Pacific Bureau Social Media November 2017 The Issues Social media is a key driver for people to go online, but there is a huge disparity in its use among Asia-Pacific countries, from a 5% penetration in Papua New Guinea to 82% in the Republic of Korea (see Figure 1) Studies have shown that social media is a Figure 1. Social media penetration rates in the Asia-Pacific region key driver for people to go online.1 It is one of the top activities on the Internet, particularly in developing countries, and is often people's first experience with the Internet.2 These platforms have surged in popularity, in parallel with the growth of mobile technology and tend to be optimised for mobile use. Social media sites have mainly been used for communication, but they are also creating new business models and incorporating multiple services (e.g., shopping, e-payment and banking, and 3 arranging transportation). Source: We Are Social, "Digital in APAC 2016," 5 September 2016 For governments, these platforms provide an opportunity to better engage with citizens: 77% of national government portals in the Asia-Pacific region have social media networking tools.4 Businesses, entrepreneurs and others are using them for marketing and branding, selling their products and services, and customer service and feedback. 1 GSMA, "Accelerating Digital Literacy: Empowering Women to Use the Mobile Internet," 2015, http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp- content/uploads/2015/06/DigitalLiteracy_v6_WEB_Singles.pdf; and World Economic Forum, "The Impact of Digital Content: Opportunities and Risks of Creating and Sharing Information Online," January 2016. -

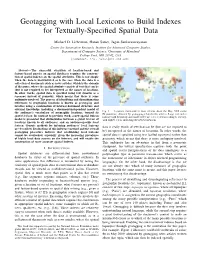

Geotagging with Local Lexicons to Build Indexes for Textually-Specified Spatial Data

Geotagging with Local Lexicons to Build Indexes for Textually-Specified Spatial Data Michael D. Lieberman, Hanan Samet, Jagan Sankaranarayanan Center for Automation Research, Institute for Advanced Computer Studies, Department of Computer Science, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742, USA {codepoet, hjs, jagan}@cs.umd.edu Abstract— The successful execution of location-based and feature-based queries on spatial databases requires the construc- tion of spatial indexes on the spatial attributes. This is not simple when the data is unstructured as is the case when the data is a collection of documents such as news articles, which is the domain of discourse, where the spatial attribute consists of text that can be (but is not required to be) interpreted as the names of locations. In other words, spatial data is specified using text (known as a toponym) instead of geometry, which means that there is some ambiguity involved. The process of identifying and disambiguating references to geographic locations is known as geotagging and involves using a combination of internal document structure and external knowledge, including a document-independent model of the audience’s vocabulary of geographic locations, termed its Fig. 1. Locations mentioned in news articles about the May 2009 swine flu pandemic, obtained by geotagging related news articles. Large red circles spatial lexicon. In contrast to previous work, a new spatial lexicon indicate high frequency, and small circles are color coded according to recency, model is presented that distinguishes between a global lexicon of with lighter colors indicating the newest mentions. locations known to all audiences, and an audience-specific local lexicon. -

Geotagging Tweets Using Their Content

Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference Geotagging Tweets Using Their Content Sharon Paradesi Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract Harnessing rich, but unstructured information on social networks in real-time and showing it to relevant audi- ence based on its geographic location is a major chal- lenge. The system developed, TwitterTagger, geotags tweets and shows them to users based on their current physical location. Experimental validation shows a per- formance improvement of three orders by TwitterTag- ger compared to that of the baseline model. Introduction People use popular social networking websites such as Face- book and Twitter to share their interests and opinions with their friends and the online community. Harnessing this in- formation in real-time and showing it to the relevant audi- ence based on its geographic location is a major challenge. Figure 1: Architecture of TwitterTagger The microblogging social medium, Twitter, is used because of its relevance to users in real-time. The goal of this research is to identify the locations refer- Pipe POS tagger1. The noun phrases are then compared with enced in a tweet and show relevant tweets to a user based on the USGS database2 of locations. Common noun phrases, that user’s location. For example, a user traveling to a new such as ‘Love’ and ‘Need’, are also place names and would place would would not necessarily know all the events hap- be geotagged. To avoid this, the system uses a greedy ap- pening in that place unless they appear in the mainstream proach of phrase chunking. -

Social Media Crisis Communication During Hurricane Matthew

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL CRISIS AND RISK Nicholson School of COMMUNICATION RESEARCH Communication and Media 2018, VOL. 1, NO 2, 279302 University of Central Florida https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.1.2.5 www.jicrcr.com Revisiting STREMII: Social Media Crisis Communication During Hurricane Matthew Margaret C. Stewart a and Cory Youngb aDepartment of Communication, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, Florida, USA; bDepartment of Strategic Communication, Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York, USA ABSTRACT Social media platforms in uence the ow of information and technologically mediated com- munication during a storm. In 2015, Stewart and Wilson introduced the STREMII (pronounced STREAM-ee) as a six-phase model for social media crisis communication in an e ort to assist institutions and organizations during unanticipated events, using the crisis of Hurricane Sandy as an applied example. Since the inception of the model, several advancements in social media strategy have revealed the opportunity for further development. This current work presents a revision of the original model, emphasizing the need for ongoing social listening and engage- ment with target audiences. These aspects of the revised model are discussed in interpersonal and organizational contexts related to examples of social media use during the October 2016 Atlantic Hurricane Matthew. KEYWORDS: Social media; crisis management; situational crisis communication theory; STREMII model; Hurricane Matthew The events of Hurricane Matthew in October 2016 resulted in a dev- astating crisis which was fully depicted via social media to engaged audiences. This hurricane event occurred during a time of innovative developments among several social media outlets, including Facebook Live, safe check-ins, and SnapChat stories.