Field Guide to the Turtles of Lake George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing Generic Concepts for Blanding's, Pacific and European

Zootaxa 2791: 41–53 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Competing generic concepts for Blanding’s, Pacific and European pond turtles (Emydoidea, Actinemys and Emys)—Which is best? UWE FRITZ1,3, CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT1 & CARL H. ERNST2 1Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Dresden, A. B. Meyer Building, D-01109 Dresden, Germany 2Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We review competing taxonomic classifications and hypotheses for the phylogeny of emydine turtles. The formerly rec- ognized genus Clemmys sensu lato clearly is paraphyletic. Two of its former species, now Glyptemys insculpta and G. muhlenbergii, constitute a well-supported basal clade within the Emydinae. However, the phylogenetic position of the oth- er two species traditionally placed in Clemmys remains controversial. Mitochondrial data suggest a clade embracing Actinemys (formerly Clemmys) marmorata, Emydoidea and Emys and as its sister either another clade (Clemmys guttata + Terrapene) or Terrapene alone. In contrast, nuclear genomic data yield conflicting results, depending on which genes are used. Either Clemmys guttata is revealed as sister to ((Emydoidea + Emys) + Actinemys) + Terrapene or Clemmys gut- tata is sister to Actinemys marmorata and these two species together are the sister group of (Emydoidea + Emys); Terra- pene appears then as sister to (Actinemys marmorata + Clemmys guttata) + (Emydoidea + Emys). The contradictory branching patterns depending from the selected loci are suggestive of lineage sorting problems. Ignoring the unclear phy- logenetic position of Actinemys marmorata, one recently proposed classification scheme placed Actinemys marmorata, Emydoidea blandingii, Emys orbicularis, and Emys trinacris in one genus (Emys), while another classification scheme treats Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys as distinct genera. -

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta)

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Family: Emydidae Characteristics: The most widespread native turtle of North America. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The adult painted turtle female is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long; the male is smaller. The turtle's top shell is dark and smooth, without a ridge. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities. The subspecies can be distinguished by their shells: the eastern has straight-aligned top shell segments; the midland has a large gray mark on the bottom shell; the southern has a red line on the top shell; the western has a red pattern on the bottom shell (Washington Nature Mapping Program). Behavior: Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators. Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud at the bottom of water bodies. Reproduction: The turtles mate in spring and autumn. Females dig nests on land and lay eggs between late spring and mid- summer. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Diet: Wild: aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish Zoo: Algae, duck food Conservation: While habitat loss and road killings have reduced the turtle's population, its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. -

Spotted Turtle,Clemmys Guttata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Spotted Turtle Clemmys guttata in Canada ENDANGERED 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Spotted Turtle Clemmys guttata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiv + 74 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2004. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the spotted turtle Clemmys guttata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 27 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Oldham, M.J. 1991. COSEWIC status report on the spotted turtle Clemmys guttata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 93 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Teresa Piraino for writing the status report on the Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen by Jim Bogart, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Tortue ponctuée (Clemmys guttata) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Spotted Turtle — Photo provided by author. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014. -

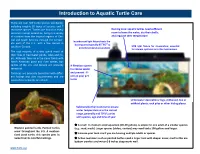

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Spotted Turtle (Clemmys Guttata) in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) in Canada Spotted Turtle 2016 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. viii + 54 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Joe Crowley Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la tortue ponctuée (Clemmys guttata) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2016. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 www.registrelep.gc.ca/default_e.cfm Recovery Strategy for the Spotted Turtle 2016 Preface The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry. -

Effectiveness of Nest Site Restoration for the Endangered Northern Map Turtle

MD-16- SHA-TU-1-03 Larry Hogan, Governor Pete K. Rahn, Secretary Boyd K. Rutherford, Lt. Governor Gregory C. Johnson, P. E., Administrator Maryland Department of Transportation STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION RESEARCH REPORT Effectiveness of Nest Site Restoration for the Endangered Northern Map Turtle Report 2: Use of Artificial Nesting Sites and Wildlife Exclusion Fence to Enhance Nesting Success Research Team Richard A. Seigel, Kaite Anderson, Brian Durkin, Jenna Cole, Sarah Cooke, and Teal Richards-Dimitrie TOWSON UNIVERSITY FINAL REPORT October 2016 The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Maryland Department of Transportation’s State Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. MD-15- SHA-TU-1-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Effectiveness of Nest Site Restoration for the Endangered Northern Map October, 2016 Turtle 6. Performing Organization Code Report 2: Use of Artificial Nesting Sites and Wildlife Exclusion Fence to Enhance Nesting Success 7. Author/s 8. Performing Organization Report No. Richard A Seigel, Kaite Anderson, Brian Durkin, Jenna Cole, Sarah Cooke, and Teal Richards-Dimitrie 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Towson University 8000 York Road 11. Contract or Grant No. Towson, MD 21252 SP509B4M 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Maryland State Highway Administration Final Report Office of Policy & Research 14. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

N.C. Turtles Checklist

Checklist of Turtles Historically Encountered In Coastal North Carolina by John Hairr, Keith Rittmaster and Ben Wunderly North Carolina Maritime Museums Compiled June 1, 2016 Suborder Family Common Name Scientific Name Conservation Status Testudines Cheloniidae loggerhead Caretta caretta Threatened green turtle Chelonia mydas Threatened hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata Endangered Kemp’s ridley Lepidochelys kempii Endangered Dermochelyidae leatherback Dermochelys coriacea Endangered Chelydridae common snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina Emydidae eastern painted turtle Chrysemys picta spotted turtle Clemmys guttata eastern chicken turtle Deirochelys reticularia diamondback terrapin Malaclemys terrapin Special concern river cooter Pseudemys concinna redbelly turtle Pseudemys rubriventris eastern box turtle Terrapene carolina yellowbelly slider Trachemys scripta Kinosternidae striped mud turtle Kinosternon baurii eastern mud turtle Kinosternon subrubrum common musk turtle Sternotherus odoratus Trionychidae spiny softshell Apalone spinifera Special concern NOTE: This checklist was compiled and updated from several sources, both in the scientific and popular literature. For scientific names, we have relied on: Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [van Dijk, P.P., Iverson, J.B., Rhodin, A.G.J., Shaffer, H.B., and Bour, R.]. 2014. Turtles of the world, 7th edition: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution with maps, and conservation status. In: Rhodin, A.G.J., Pritchard, P.C.H., van Dijk, P.P., Saumure, R.A., Buhlmann, K.A., Iverson, J.B., and Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs 5(7):000.329–479, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v7.2014; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. -

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina Rylen Nakama FISH 423: Olden 12/5/14 Figure 1. The Common Snapping Turtle, one of the most widespread reptiles in North America. Photo taken in Quebec, Canada. Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/yorthopia/7626614760/. Classification Order: Testudines Family: Chelydridae Genus: Chelydra Species: serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) Previous research on Chelydra serpentina (Phillips et al., 1996) acknowledged four subspecies, C. s. serpentina (Northern U.S. and Figure 2. Side profile of Chelydra serpentina. Note Canada), C. s. osceola (Southeastern U.S.), C. s. the serrated posterior end of the carapace and the rossignonii (Central America), and C. s. tail’s raised central ridge. Photo from http://pelotes.jea.com/AnimalFact/Reptile/snapturt.ht acutirostris (South America). Recent IUCN m. reclassification of chelonians based on genetic analyses (Rhodin et al., 2010) elevated C. s. rossignonii and C. s. acutirostris to species level and established C. s. osceola as a synonym for C. s. serpentina, thus eliminating subspecies within C. serpentina. Antiquated distinctions between the two formerly recognized North American subspecies were based on negligible morphometric variations between the two populations. Interbreeding in the overlapping range of the two populations was well documented, further discrediting the validity of the subspecies distinction (Feuer, 1971; Aresco and Gunzburger, 2007). Therefore, any emphasis of subspecies differentiation in the ensuing literature should be disregarded. Figure 3. Front-view of a captured Chelydra Continued usage of invalid subspecies names is serpentina. Different skin textures and the distinctive pink mouth are visible from this angle. Photo from still prevalent in the exotic pet trade for C. -

Movement and Habitat Use of Two Aquatic Turtles (Graptemys Geographica and Trachemys Scripta) in an Urban Landscape

Urban Ecosyst DOI 10.1007/s11252-008-0049-8 Movement and habitat use of two aquatic turtles (Graptemys geographica and Trachemys scripta) in an urban landscape Travis J. Ryan & Christopher A. Conner & Brooke A. Douthitt & Sean C. Sterrett & Carmen M. Salsbury # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract Our study focuses on the spatial ecology and seasonal habitat use of two aquatic turtles in order to understand the manner in which upland habitat use by humans shapes the aquatic activity, movement, and habitat selection of these species in an urban setting. We used radiotelemetry to follow 15 female Graptemys geographica (common map turtle) and each of ten male and female Trachemys scripta (red-eared slider) living in a man-made canal within a highly urbanized region of Indianapolis, IN, USA. During the active season (between May and September) of 2002, we located 33 of the 35 individuals a total of 934 times and determined the total range of activity, mean movement, and daily movement for each individuals. We also analyzed turtle locations relative to the upland habitat types (commercial, residential, river, road, woodlot, and open) surrounding the canal and determined that the turtles spent a disproportionate amount of time in woodland and commercial habitats and avoided the road-associated portions of the canal. We also located 21 of the turtles during hibernation (February 2003), and determined that an even greater proportion of individuals hibernated in woodland-bordered portions of the canal. Our results clearly indicate that turtle habitat selection is influenced by human activities; sound conservation and management of turtle populations in urban habitats will require the incorporation of spatial ecology and habitat use data. -

Those Other Turtles (Spotted, Wood)

Those Other Turtles by Rob Criswell photos by the author Spotted turtle www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater, September-October 2003 49 Wood turtle neck. The plastron (lower shell), on the other hand, is yellow with a few dark or black markings. The largest member of this small genus is the wood turtle. Wood turtles typically range from 6.5 to 7 inches in carapace length, with males normally exceeding females by a half-inch or so. The species record is a 9- inch-plus whopper. Although wood turtles do not flaunt the “bright on black” of their smaller cousin, their scientific species name, insculpta, which translates to “engraved,” or “sculptured,” is descriptive and appropriate. The strik- ingly distinctive scutes of the upper shell resemble individually chiseled pyramids. Each of these raised plates is embedded with a series of concentric growth rings, or “annuli,” similar to those found in the cross section of a tree trunk or limb. This phenomenon, coupled with the similarity of the rough, brownish carapace to a piece of carved wood, may account for this tortoise’s common name, although some argue it’s based on its habit of frequenting forested areas. Attempting to age a wood turtle by counting its “rings,” however, is not as nearly precise as when dealing with trees. Although a fairly accurate determination may be made for younger “woodies,” such counts for turtles approaching 20 years or older are unreliable. Although the subdued color scheme of the upper shell is overshadowed by its “sculptures,” the plastron is a study in contrast, with large, black blotches displayed on a light- yellow background. -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location.