Cello Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

11 7 Thseason

2016- 17 (117TH SEASON) Repertoire Bach Cantata No. 150, “Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget Feb. 23-25, 2017 mich”* Violin Concerto No. 1 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Bartók Bluebeard’s Castle Mar. 2-4, 2017 Bates Alternative Energy* Apr. 6-9, 2017 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Feb. 2-4, 2017 Selections from The Creatures of Prometheus Apr. 6-9, 2017 Symphony No. 2 Dec. 8-10, 2016 Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) Mar. 10-12, 2017 Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”) Nov. 25-27, 2016 Violin Concerto Nov. 3-5, 2016 Berg Violin Concerto Mar. 10-12, 2017 Berlioz Le Corsaire Overture Oct. 7-8, 2016 Harold in Italy Jan. 26-27, 2017 Symphonie fantastique Sep. 22-24, 2016; Oct. 7-8, 2016 Bernstein Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs Mar. 30-Apr. 1, 2017 Symphony No. 1 (“Jeremiah”) May 3-6, 2017 Brahms Symphony No. 1 Oct. 27-29, 2016 Symphony No. 2 Nov. 3-5, 2016 Symphony No. 3 Feb. 17-19, 2017 Symphony No. 4 Feb. 23-25, 2017 Brahms/transcr. Selections from Eleven Choral Preludes Feb. 23-25, 2017 Glanert (world premiere of transcriptions) Britten War Requiem Mar. 23-25, 2017 Canteloube Selections from Songs of the Auvergne Jan. 12-14, 2017 Chabrier Joyeuse Marche** Jan. 12-14, 2017 – more – January 2016—All programs and artists subject to change. PAGE 2 The Philadelphia Orchestra 2016-17 Season Repertoire Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 Jan. 19-24, 2017 Piano Concerto No. 2 Sep. 22-24, 2016 Dutilleux Métaboles Oct. 27-29, 2016 Dvořák Symphony No. 8 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Symphony No. -

Playlist 12 - Wednesday, June 24Th, 2020

Legato in Times of Staccato Playlist 12 - Wednesday, June 24th, 2020 Curated by Music Director, Fouad Fakhouri William Dawson: Negro Folk Symphony William Dawson was a renowned African American composer, choir director, and professor who incorporated African American themes and melodies into his music. With the Negro Folk Symphony, Dawson aimed to “write a symphony in the Negro folk idiom, based on authentic folk music but in the same symphonic form used by the composers of the [European] romantic-nationalist school.” The work consists of three movements, each with its own programmatic subtitle. Dvorak: Serenade for Strings & Wind Dvořák composed his entire Serenade in E major for string orchestra in less than two weeks in May 1875. The piece is in five movements, and in the finale, the main theme from the first movement is quoted before the coda, effectively unifying the work. Overall, the piece is light and carefree, reflecting a happy and productive time in Dvořák’s life. The Serenade in D minor for wind instruments was also composed in just two weeks in January 1878. The winds play atop a foundation of cello and string bass, and like in the Serenade for Strings, the opening theme is quoted in the final movement to unify the piece. The work is Classical in form but Czech in character as Dvořák incorporated folk melodies and rhythms from his native Bohemian culture. The piece was dedicated to music critic Louis Ehlert who promoted Dvořák’s famous Slavonic Dances and helped to advance Dvořák’s musical career. Haydn: Cello Concerto No. 1 Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. -

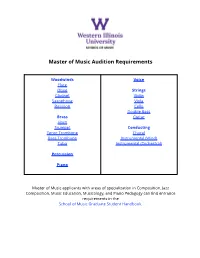

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Cellist Zuill Bailey with Helen Kim and the KSU Symphony Orchestra

SCHOOL of MUSIC where PASSION is Zuill Bailey,heard Cello featuring Helen Kim, Violin Robert Henry, Piano KSU Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director and Conductor Wednesday, October 9, 2019 | 8:00 PM Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall musicKSU.com 1 heard Program LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) CAPRICCIO MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) KOL NIDREI, OPUS 47 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME, OPUS 33 Zuill Bailey, Cello Robert Henry, Piano –INTERMISSION– JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN, CELLO, AND ORCHESTRA IN A MINOR, OPUS 102 I. ALLEGRO II. ANDANTE III. VIVACE NON TROPPO Zuill Bailey, Cello Helen Kim, Violin Kennesaw State University Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Conductor We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: easy access, companion seating locations, accessible restrooms, and assisted listening devices. Please contact a patron services representative at 470-578-6650 to request services. 2 Kennesaw State University School of Music KSU Symphony Orchestra Personnel Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director & Conductor Personnel listed alphabetically to emphasize the importance of each part. Rotational seating is used in all woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Flute Violin Cello Don Cofrancesco Melissa Ake^, Garrett Clay Lorin Green concertmaster Laci Divine Jayna Burton Colin Gregoire^, principal Oboe Abigail Carpenter Jair Griffin Emily Gunby Robert Cox^ Joseph Grunkmeyer, Robert Simon Mary Catherine Davis associate principal -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ.