Alice's Adventures and Bleak House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasy Favourites from Abarat to Oz!

Fantasy Favourites From Abarat To Oz! Fans of hobbits and Harry Potter have had a magical SS TED PRE TED A I C effect on the world of O SS fantasy fiction. We take A you inside this exploding J.R.R. Tolkien genre where the impossible is possible! BY DAVID MARC FISCHER J.K. Rowling © Pierre Vinet/New Line Productions Vinet/New © Pierre © 2009 Scholastic Canada Ltd. V001 Flights of Fantasy 1 of 12 eroes and heroines. Fantasy books have lightning-bolt scar and a Dungeons and dragons. frequently dominated the knack for riding broomsticks. H Swords, sorcerers, U.S. Young Adult Library When J.K. Rowling’s first witches, and warlocks. It’s the Services Association poll of Harry Potter book hit U.S. stuff of fantasy fiction, and it young readers’ favourites. bookstores in 1998, no one has cast a powerful spell on Books on the Top Ten list could have predicted its teen readers everywhere. have included Cornelia impact. Harry Potter and the “Fantasy fiction has helped Funke’s The Thief Lord, Garth Sorcerer’s Stone (“Philosopher’s sculpt the person I am today,” Nix’s Abhorsen, and Holly Stone” in Canada) topped says 17-year-old Nick Feitel, who Black’s Title: the best-seller lists, where it enjoys fantasy sagas from J.R.R. A Modern Faerie Tale. was quickly followed by every Tol k ien’s The Lord of the Rings to other book in the series. Tamora Pierce’s Circle of Magic. POTTER POWER The boy wizard you grew up “I think I became a lot more Why is fantasy so popular with continued to set sales creative as a result of reading among young readers? records. -

Gothic Visions of Classical Architecture in Hablot Knight Browne's 'Dark' Illustrations for the Novels of Charles Dickens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Janes, Dark illustrations, revised version, p. 1 Gothic Visions of Classical Architecture in Hablot Knight Browne’s ‘Dark’ Illustrations for the Novels of Charles Dickens Figs. 1. A. W. N. Pugin, detail, ‘Contrasted Residences for the Poor’, Contrasts (1836). 2. H. K. Browne, ‘The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold’, Bleak House (1853). 3. H. K. Browne, ‘Little Dorrit’s Party’, Little Dorrit (1856). 4. H. K. Browne, ‘Damocles’, Little Dorrit (1857). 5. H. K. Browne, ‘The Birds in the Cage’, Little Dorrit (1855). 6. H. K. Brown, working sketch, ‘The River’, David Copperfield, Elkins Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia (1850). 7. H. K. Browne, ‘The River’, David Copperfield (1850). Early Victorian London was expanding at a furious pace. Much of the new suburban housing consisted of cheap copies of Georgian neo-classicism. At the same time a large part of the city’s centre, a substantial proportion of which had been rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666, had fallen into decay. The alarming pace of change in the built environment was mirrored by that in the political realm. The threat of revolution, it was widely believed, could only be ended by a significant programme of reform but there was no consensus as to whether that should be essentially institutional, financial or moral. In these circumstances the past, and its material evidences, came to play a prominent role in the public imagination, as either a source of vital tradition or of dangerous vice and complacency. -

Fiyj-W-MULLER

* fiyJ-w-MULLER .. Jarndyce still insisted that she must called the study. It was not a grim be nor taken by surprise, Growlery, though John Jarndyce pro- not hurried, to re- tested that it had been a quite fero- and that she must have time cious place before Dame Durden became consider before she bound her youth to an occupant of It. He declared that be- his age. So nothing was said to any fore then the wind had been east with one in Bleak House or out, and thlnge Dickens' women are not his surprising constancy. Esther only good even way till4>n® laughed, for she had learned very early went on in their quiet, "strongest" characters. Madeline Bray remembrance tokens of affectionate that whenever John met of news shook and Kate Nickleby In "Nicholas Nickle- Jarndyce some morning a startling piece that It made her feel almost ashamed or trouble that he could by;" Mary Graham In "Martin Chuzzle- disappointment them. have done so little and have won so not hide from everybody he hid himself wlt;" Rose Maylle in “Oliver Twist;'' to The news was that Mr. Tulklnghorn behind the excuse that the wind must Florence Dombey In "Dombey and Son;’’ much. had been found dead In his room, and be east. the Emma Haredale In "Barnaby Rudge;" When these six years had passed, a that he had been shot through She had so much reason to be happy, Little Dorrit in the novel of that name; heart. letter came from the lawyer saying she had such reason to be grateful, even Lizzie Hexam in "Our Mutual Her mother’s dread of the man. -

Are You Alice?: V. 1 Free Ebook

FREEARE YOU ALICE?: V. 1 EBOOK Ikumi Katagiri | 192 pages | 28 May 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316250955 | English | New York, United States Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International - Wikipedia Build up your Halloween Watchlist with our list of the most popular horror titles on Netflix in October. See the list. Everything you know about Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is about to be turned upside down in this modern-day mini-series. The first thing that must be said is that this is not the original Alice in Wonderland. Honestly, anybody who thinks it is They Are You Alice?: v. 1 it in the very first commercials that this was "different" so from the Are You Alice?: v. 1 go you shouldn't expect Carrol's book. This is a completely different take on Wonderland and Looking Glass - and it's good! It presents us with a headstrong and kind of reckless Alice who is capable of taking care of herself. And Hatter is just awesome, he really is. The Queen makes me want to punchasize her face which is a good thing, it means Bates played her role well and the White Knight Ah, what can I say about the White Knight besides, "Most awesome old guy ever? I expected it from Sci-fi or Syfy, whatever. But that doesn't stop this from being a good miniseries. It was well acted, well written, and fun! I must reiterate: This wasn't meant to be the children's story, it was meant to be a different take on the story and aim it towards a different audience! A good miniseries and well worth watching if you can accept that this really Are You Alice?: v. -

Takes Alice to a Very Different Wonderland November 4, 2009 | 5:43 Am

Hero Complex For your inner fanboy 'Looking Glass Wars' takes Alice to a very different Wonderland November 4, 2009 | 5:43 am The rabbit hole is getting crowded again. It’s been 144 years since Lewis Carroll introduced the world to an inquisitive girl named Alice, but her surreal adventures still resonate – Tim Burton’s “Alice in Wonderland” arrives in theaters in March and next month on SyFy it's “Alice,” a modern-day reworking of the familiar mythology with a cast led by Kathy Bates and Tim Curry. And then there’s “The Looking Glass Wars,” the series of bestselling novels by Frank Beddor that takes the classic 19th century children’s tale off into a truly unexpected literary territory – the battlefields of epic fantasy. The series began in 2006 and Beddor’s third “Looking Glass Wars” novel, “ArchEnemy,” just hit stores in October, as did a tie-in graphic novel called “Hatter M: Mad with Wonder.” Beddor said it’s intriguing to see other creators at play in the same literary playground. “It’s amazing how many directions it’s been taken in,” Beddor said of Carroll’s enduring creations. “There’s something so rich and magical and whimsical about the original story and the characters and then there’s all those dark under-themes. Artists get inspired and they keep redefining it for a contemporary audience.” Indeed, creative minds as diverse as Walt Disney, the Jefferson Airplane, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Tom Petty, the Wachowski Brothers, Tom Waits and American McGee have adapted Carroll’s tale or borrowed memorably from its imagery. -

Alphabetical List Updated 11/15/2013

Alphabetical List Updated 11/15/2013 Movie Name Movie ID Movie Name Movie ID 255 Avengers, The 493 1408 1 Baby Mama 337 15 Minutes 240 Back to the Future 614 2 Fast 2 Furious 2 Bad Boys II 387 2001: A Space Odyssey 598 Bad Education 471 21 Jump Street 487 Bad Teacher 386 24: Season 1 680 Bandits 15 24: Season 2 681 Barbershop 16 24: Season 3 682 Basic 17 27 Dresses 509 Batman Begins 543 28 Days Later 677 Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker 18 3 Idiots 570 Battlestar Galactica: Season 1 649 3:10 to Yuma 3 Battlestar Galactica: Season 2.0 650 300 4 Battlestar Galactica: Season 2.5 651 40-Year Old Virgin, The 590 Battlestar Galactica: The Miniseries 640 50/50 406 Be Cool 20 A View to a Kill 561 Beasts of the Southern Wild 544 A-Team, The 243 Beautiful Thing 403 Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 514 Beauty Shop 19 Adjustment Bureau, The 494 Bee Movie 21 Aguirre, Wrath of God 524 Before Midnight 690 Air Force One 685 Before Sunrise 22 Albert Nobbs 470 Beowulf 23 Alice in Wonderland 6 Best in Show 24 All Good Things 504 Best Man, The 348 Almost Famous 7 Bicentennial Man, The 601 Amazing Spiderman, The 525 Big Fish 701 American Beauty 241 Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure 25 American Gangster 8 Black Dynamite 415 American History X 242 Black Hawk Down 26 American Violet 464 Black Snake Moan 27 Amores Perros 9 Black Swan 325 Amour 695 Blades of Glory 28 An American in Paris 388 Blair Witch Project, The 29 Anastasia 592 Blind Side, The 244 Anger Management 10 Blood Diamond 30 Animal House 239 Bourne Identity, The 31 Animatrix 390 Bourne Legacy, The -

Representation of Angel-In-The-House in Bleak House by Charles Dickens

THEORY, HISTORY AND LITERARY CRITICISM Representation of Angel-in-the-House in Bleak house by Charles Dickens Shaghayegh Moghari Abstract: This article intends to examine the female characters of Esther Summerson and Ada Clare in Bleak House, written by Charles Dickens in Victorian period. In fact, the author has tried to revisit this novel as a case in point to discuss how female characters in Victorian society, who were depicted typically in this Victorian novel, were labeled as “angel in the house”. This work will actually analyze the concept of “angel in the house,” hegemonic patriarchy, Esther Summerson, Ada Care, and Lady Dedlock as Esther’s foil. At the end, this article will discuss how in the Victorian male-dominated society women were easily manipulated by their male counterparts both in society and at home under the label of “angel in the house”. Keywords: “angel in the house”, Esther Summerson, Ada Clare, Victorian society, Bleak house, patriarchy, women 1. INTRODUCTION Esther Summerson, as a Victorian model of woman, is marvelously perfect in numerous ways. The qualities which she possesses in the novel include prettiness, humbleness, modesty, quietness, assiduousness, and thankfulness. She is a good caretaker, and homemaker who usually has a habit of working only for the benefit of others. These qualities are what the society of her time desired from her as a woman and she did stick to these criteria as a woman. Charles Dickens in his book informs us about Esther. The Victorian society advocated ‘Submission, self-denial, diligent work’ since these qualities were considered as the preparations that the society expected from women in order to regard them as qualified for a marriage. -

I “Attached to Life Again” Esther Summerson's Struggle for Identity and Acceptance in Bleak House

“Attached to life again” Esther Summerson’s Struggle for Identity and Acceptance in Bleak House i Contents Acknowledgements Page iii Introduction Pages 1 - 2 Chapter One: Critical Views of Esther’s Narrative Pages 3 - 12 Chapter Two: Dickens as Depth Psychologist Pages 13 - 17 Chapter Three: Structure and Theme in Esther’s Narrative Pages 18 - 23 Chapter Four: “Set Apart”: Esther’s Psychological Development and “Attachment Theory” Pages 24 - 33 Chapter Five: Esther’s Dream Life Pages 34 - 42 Chapter Six: Conclusion Pages 43 - 45 Appendix Pages 46 - 48 Works Cited Pages 49 - 51 ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the following people for assisting me in this work, and in my studies. The late Dr. Charles Hart, Assistant Dean of Arts and Sciences at Loyola University, first introduced me to the Victorian novel, and encouraged me to continue my undergraduate studies in English Literature. Dr. Nancy Carr, some twenty-five years later, rekindled my interest in the Victorian novel, and in Bleak House in particular. Thanks also to Dr. Daniel Born who has guided me through the process of selecting a topic for this paper, writing and editing the work, and providing counsel along the way, including speculation on the identity of the omniscient narrator, which I have used in the Appendix to this paper. Thanks also to Dr. Jennifer Brody, who agreed to act as a second reader for the paper despite the fact that she has relocated and has many demands on her time. iii Introduction In the preface to Bleak House, Charles Dickens wrote that he “purposely dwelt upon the romantic side of familiar things” (xxxv). -

Phiz - the Man Who Drew Dickens

Phiz - the Man who drew Dickens Of the many colourful characters in the Bicknell ancestry, Phiz is possibly the most appealing. His story is also more credibly documented than the pre-Victorians whose courage in battle or other achievements seem now to have been embellished by the now-notorious Sydney Algernon Bicknell, our Victorian family archivist. Phiz, or Hablot Knight Browne to give him his proper name, is the subject of a wonderful book published in late 2004 by his great-great-granddaughter Valerie Browne Lester. For over 23 years he worked with Charles Dickens and Phiz 's drawings brought to life a galaxy of much-loved characters, from Mr Pickwick, Nicholas Nickleby and Mr Micawber to Little Nell and David Copperfield. Phiz lived a life as rich as any novel and Valerie's rendition of life in Victorian London is enchanting. Of great interest to his family, which includes the Bicknells, is the mystery of his birth, which Valerie has researched in great detail for the first time. Phiz came from an old Huguenot Spitalfields family, ostensibly the fourteenth child of debt-ridden parents, William Loder Browne and Katherine Hunter. Now it turns out that the eldest daughter Kate had an affair in France with Captain Nicholas Hablot of Napoleon's Imperial Guard; a month before Hablot's birth the true father was killed at the battle of Waterloo. Kate's parents "adopted" Kate's illegitimate son and falsified the birth papers of both Hablot and their own son Decimus born embarrassingly close. Lucinda, Kate's younger sister was 14 at the time. -

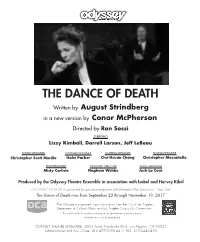

THE DANCE of DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a New Version by Conor Mcpherson Directed by Ron Sossi

THE DANCE OF DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a new version by Conor McPherson Directed by Ron Sossi STARRING Lizzy Kimball, Darrell Larson, Jeff LeBeau SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Christopher Scott Murillo Halei Parker Chu-Hsuan Chang Christopher Moscatiello PROP DESIGNER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR STAGE MANAGER Misty Carlisle Nagham Wehbe Josh La Cour Produced by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in association with Isabel and Harvey Kibel THE DANCE OF DEATH is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service Inc., New York The Dance of Death runs from September 23 through November 19, 2017 The Odyssey is supported in part by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs, and Los Angeles County Arts Commission The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE: 2055 South Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025 Administration and Box Office: 310-477-2055 ext 2 FAX: 310-444-0455 CAST (in order of appearance) THE CAPTAIN .................................................................Darrell Larson ALICE .............................................................................Lizzy Kimball KURT .................................................................................Jeff LeBeau SETTING An Island Fortress near a port in Sweden, Early 20th Century Running time: Two hours There will be one fifteen-minute intermission. This production is dedicated to Sam Shepard. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Dance of Death has amazing significance to the whole world of contemporary drama. The "trapped" nature of its characters feels like Sartre's No Exit (and its classic line "Hell is other people"). And its foreshadow- ing of Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is uncannily prescient, almost as if Albee "channeled" Strindberg in cooking up his own mixture of raucous verbal battle and deadly humor. -

Encountering Charles Dickens: the Lawyer's Muse1

Athens Journal of Law 2021, 7: 1-9 https://doi.org/10.30958/ajl.X-Y-Z Encountering Charles Dickens: The Lawyer’s Muse1 By Michael P. Malloy* This article explores the themes of the practical impact of law in society, the life of the law, and the character of the lawyer (in both senses of the term), as reflected in the works of Charles Dickens. I argue that, in creating memorable scenes and images of the life of the law, Charles Dickens is indeed the lawyer’s muse. Dickens – who had worked as a junior clerk in Gray’s Inn and a court reporter early in his career – outpaces other well-known writers of “legal thrillers” when it comes to assimilating the life of the law into his literary works. The centrepiece in this regard is an extended study and analysis of Bleak House. The novel is shaped throughout by a challenged and long-running estate case in Chancery Court, and it is largely about the impact of controversy on the many lawyers involved in the case. It has all the earmarks of a true “law and literature” text - a terrible running joke about chancery practice, serious professional responsibility issues, and a murdered lawyer.1 Keywords: Charles Dickens; Law and Literature; the Life of the Law. Introduction In a seminar focused on the Law and Literature movement,2 it is almost impossible to ignore Charles Dickens. He is in many respects the chronicler of law and lawyers. So many iconic images of the life of the law are of his devising. -

Are You Alice?: V. 1 Free

FREE ARE YOU ALICE?: V. 1 PDF Ikumi Katagiri | 192 pages | 28 May 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316250955 | English | New York, United States Alice – Tell Stories. Build Games. Learn to Program. Build up your Halloween Watchlist with our list of the most popular Are You Alice?: v. 1 titles on Netflix in October. See the list. Everything you know about Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is about to be turned upside down in this modern-day mini-series. The first thing that must be said is that this is not the original Alice in Wonderland. Honestly, anybody who thinks it is They said Are You Alice?: v. 1 in the very first commercials that this was "different" so from the get go you shouldn't expect Carrol's book. This is a completely different take on Wonderland and Looking Glass - and it's good! It presents us with a headstrong and kind of reckless Alice who is capable of taking care of herself. And Hatter is just awesome, he really is. The Queen makes me want to punchasize her face which is a good thing, it means Bates played her role well and the White Knight Ah, what can I say about the White Knight besides, "Most awesome old guy ever? I expected it from Sci-fi or Syfy, whatever. But that doesn't stop this from being a good miniseries. It was well acted, well written, and fun! I must reiterate: This wasn't meant to be the children's story, it was meant to be a different take on the story and aim it towards a different audience! A good miniseries and well worth watching if you can accept that this really is "a different kind of Alice.