Johnson Et Al. V. Zuffa, LLC Et

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

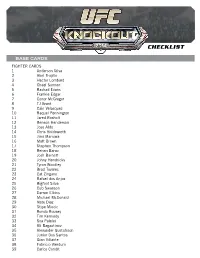

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Absolute Championship Berkut History+Geography

ABSOLUTE CHAMPIONSHIP BERKUT HISTORY+GEOGRAPHY The MMA league Absolute Championship Berkut was founded in early 2014 on the basis of the fight club “Berkut”. The first tournament was held by the organization on March 2 and it marked the beginning of Grand Prix in two weight divisions. In less than two years the ACB company was able to become one of three largest Russian MMA organizations. Also, a reputable independent website fightmatrix.com named ACB the number 1 promotion in our country. 1 GEOGRAPHY BELGIUM The geography of the tournaments covered GEORGIA more than 10 Russian cities, as well as Tajikistan, Poland, Georgia and Scotland. 50 MMA tournaments, 8 kickboxing ones HOLLAND POLAND and 3 Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments will be held by the promotion by the end of 2016 ROMANIA TAJIKISTAN SCOTLAND RUSSIA 2 OUR CLIENT’S PORTRAIT AGE • 18-55 YEARS OLD TARGET AGE • 23-29 YEARS OLD 9\1 • MEN\WOMEN Income: average and above average 3 TV BROADCAST Tournaments are broadcast on TV channels Match!Fighter and BoxTV as well as online. Average audience coverage per tournament: - On TV - 500,000 viewers; - Online - 150,000 viewers. 4 Media coverage Interviews with participants of the tournament are regularly published in newspapers and on websites of leading Russian media: SPORTBOX.RU, R- SPORT.RU, CHAMPIONAT.COM, MMABOXING.RU, ALLFIGHT.RU , etc. Foremost radio stations, Our Radio, Rock FM, Sport FM, etc. also broadcast the interviews. 5 INFORMATION SUPPORT Our promotion is also already well known outside Russia. Tournament broadcasts and the main news of the league regularly appear on major international websites: 6 Social networks coverage THOUSAND 400 SUBSCRIBERS 4,63 MILLION VIEWS 7 COMPANY MANAGEMENT The founder of the ACB league is one of the most respected citizens of the Chechen Republic – Mairbek Khasiev. -

Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 Of

Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 2 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 3 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 4 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 5 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 6 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 7 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 8 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 9 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 10 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 11 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 12 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 13 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 14 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 15 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 16 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 17 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 18 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 19 of 502 1 CYCLE CENTER H/D 1-ELEVEN INDUSTRIES 100 PERCENT 107 YEARICKS BLVD 3384 WHITE CAP DR 9630 AERO DR CENTRE HALL PA 16828 LAKE HAVASU CITY AZ 86406 SAN DIEGO CA 92123 100% SPPEDLAB LLC 120 INDUSTRIES 1520 MOTORSPORTS 9630 AERO DR GERALD DUFF 1520 L AVE SAN DIEGO CA 92123 30465 REMINGTON RD CAYCE SC 29033 CASTAIC CA 91384 1ST AMERICAN FIRE PROTECTION 1ST AYD CO 2 CLEAN P O BOX 2123 1325 GATEWAY DR PO BOX 161 MANSFIELD TX 76063-2123 ELGIN IN 60123 HEISSON WA 98622 2 WHEELS HEAVENLLC 2 X MOTORSPORTS 241 PRAXAIR DISTRIBUTION INC 2555 N FORSYTH RD STE A 1059 S COUNTRY CLUB DRRIVE DEPT LA 21511 ORLANDO FL 32807 MESA AZ -

Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking

Kimberly Owczarski Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking In June 2005, Warner Bros. Pictures announced Are Marshall (2006), and Trick ‘r’ Treat (2006)2— a multi-film co-financing and co-production not a single one grossed more than $75 million agreement with Legendary Pictures, a new total worldwide at the box office. In 2007, though, company backed by $500 million in private 300 was a surprise hit at the box office and secured equity funding from corporate investors including Legendary’s footing in Hollywood (see Table 1 divisions of Bank of America and AIG.1 Slate for a breakdown of Legendary’s performance at financing, which involves an investment in a the box office). Since then, Legendary has been a specified number of studio films ranging from a partner on several high-profile Warner Bros. films mere handful to dozens of pictures, was hardly a including The Dark Knight, Inception, Watchmen, new phenomenon in Hollywood as several studios Clash of the Titans, and The Hangoverand its sequel. had these types of deals in place by 2005. But In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, the sheer size of the Legendary deal—twenty five Legendary founder Thomas Tull likened his films—was certainly ambitious for a nascent firm. company’s involvement in film production to The first film released as part of this deal wasBatman an entrepreneurial endeavor, stating: “We treat Begins (2005), a rebooting of Warner Bros.’ film each film like a start-up.”3 Tull’s equation of franchise. Although Batman Begins had a strong filmmaking with Wall Street investment is performance at the box office ($205 million in particularly apt, as each film poses the potential domestic theaters and $167 million in international for a great windfall or loss just as investing in a theaters), it was not until two years later that the new business enterprise does for stockholders. -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

The Licking Valley Courier Thursday, March 27, 2008 Page One-B

TheThe LickingLicking ValleyValley CourierCourier Morgan County’s HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER Speaking Of and For Morgan, the Bluegrass County of the Mountains Since 1910 (USPS 312-040) Morgan County Courthouse - Built 1907 Per $22.50 Year In County Volume 97 — No. 32 WEST LIBERTY, KENTUCKY 41472, THURSDAY, MARCH 27, 2008 ¢ $25.00 Year In Kentucky 50 Copy $27.00 Year Outside Kentucky City Council Court adopts tax again tables amendment package, avoids to dog law By Miranda Cantrell James takeover by state The West Liberty City Coun- cil at its regular March 24 meet- Measures pass 3-2 with one abstention ing voted again to table for fur- Ordinances imposing a one county’s long-standing budget ther discussion a proposed half of one percent county pay- problems. amendment of the city’s dog law roll tax and increasing the The new taxes are expected to ordinance to impose higher fines county’s insurance premium tax generate approximately for violations. by 2.5 percent — from 2.5 to 4.5 $575,000 annually, which will Mayor Bob Nickell expressed percent — got their second read- allow the magistrates to escape a desire to repeal and update the ings Monday and were adopted incurring a deficit in the county’s current ordinance, which requires by the fiscal court on a vote of 3 current budget and allow work to police officers to impound stray to 2 with one abstention. begin on preparation of a new dogs. The two revenue-enhancing budget for 2008-2009. “This is a liability issue,” measures, which received their Judge Executive Tim Conley Nickell said. -

Hit Show Dana White's Contender Series

HIT SHOW DANA WHITE’S CONTENDER SERIES CONTINUES ITS FOURTH SEASON WITH EPISODE 7 AIRING LIVE TUESDAY FROM UFC APEX IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas – The fourth season of the hit show Dana White’s Contender Series continues with Episode 7, featuring a lineup of rising athletes looking to make their dreams come true by impressing UFC President Dana White and earning a spot on the UFC roster. The seventh episode of season four takes place on Tuesday, September 15 at 8 p.m. ET / 5 p.m. PT, with all five bouts streaming exclusively on ESPN+ in the US. ESPN+ is available through the ESPN.com, ESPNPlus.com or the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Fans can sign up for $4.99 per month or $49.99 per year, with no contract required. To support your coverage, please find the download link to the season four sizzle reels here and here. In addition, please find the download link for the season four athlete feature here, which highlights some of the participating athletes, their backgrounds and what competing on Dana White’s Contender Series means to them. Season 4, Episode 7 – Confirmed Bouts: Middleweight Gregory Rodrigues vs. Jordan Williams Featherweight Muhammad Naimov vs. Collin Anglin Welterweight Korey Kuppe vs. Michael Lombardo Women’s featherweight Danyelle Wolf vs. Taneisha Tennant Featherweight Dinis Paiva vs. Kyle Driscoll Visit the UFC.com for information and additional content to support your UFC coverage. -

Brandon Vera, Et Al. V. Zuffa, LLC, D/B/A Ultimate

Case5:14-cv-05621 Document1 Filed12/24/14 Page1 of 63 1 Joseph R. Saveri (State Bar No. 130064) Joshua P. Davis (State Bar No. 193254) 2 Andrew M. Purdy (State Bar No. 261912) Kevin E. Rayhill (State Bar No. 267496) 3 JOSEPH SAVERI LAW FIRM, INC. 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 625 4 San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: (415) 500-6800 5 Facsimile: (415) 395-9940 [email protected] 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 [email protected] 8 Benjamin D. Brown (State Bar No. 202545) Hiba Hafiz (pro hac vice pending) 9 COHEN MILSTEIN SELLERS & TOLL, PLLC 1100 New York Ave., N.W., Suite 500, East Tower 10 Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 408-4600 11 Facsimile: (202) 408 4699 [email protected] 12 [email protected] 13 Eric L. Cramer (pro hac vice pending) Michael Dell’Angelo (pro hac vice pending) 14 BERGER & MONTAGUE, P.C. 1622 Locust Street 15 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Telephone: (215) 875-3000 16 Facsimile: (215) 875-4604 [email protected] 17 [email protected] 18 Attorneys for Individual and Representative Plaintiffs Brandon Vera and Pablo Garza 19 [Additional Counsel Listed on Signature Page] 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 21 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION 22 Brandon Vera and Pablo Garza, on behalf of Case No. 23 themselves and all others similarly situated, 24 Plaintiffs, ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 25 v. 26 Zuffa, LLC, d/b/a Ultimate Fighting DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Championship and UFC, 27 Defendant. 28 30 Case No. 31 ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 32 Case5:14-cv-05621 Document1 Filed12/24/14 Page2 of 63 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 3 I. -

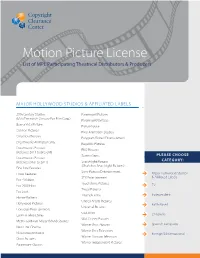

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Brooks, UFC, Mars Giving Las Vegas Big Back-To- Back Weekends by Richard N

Brooks, UFC, Mars giving Las Vegas big back-to- back weekends By Richard N. Velotta Las Vegas Review-Journal July 8, 2021 - 11:14 pm Normally, there’s a tourism lull the week after a three-day weekend. But as everyone knows, 2021 is far from normal, and the weekend after the three-day Fourth of July holiday has the makings of a blockbuster for Las Vegas. Credit a supercluster of blockbuster entertainment coming up in the city this weekend. The UFC 264 event at T-Mobile Arena, featuring Conor McGregor-Dustin Poirier. Garth Brooks at Allegiant Stadium. Bruno Mars at Park MGM. On top of that, former President Donald Trump is planning to attend the big fight, UFC President Dana White confirmed Thursday. The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority doesn’t have any historical data to calculate an estimate of how many people will venture to Las Vegas this weekend, but most observers think more than 300,000 people were in the city over the Fourth of July three-day holiday. Will 300,000 more be here this weekend? Testing transportation If nothing else, the existing transportation grid will be put to the test with three major events — the Garth Brooks concert, the UFC fights and Bruno Mars — occurring at venues within a half-mile of each other at right around the same time that night. But health officials have expressed concern that big crowds have the potential to create superspreader events. Nevada on Thursday reported 697 new coronavirus cases and two deaths as the state’s test positivity rate continued to climb. -

UFC) Started in 1993 As a Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) Tournament on Pay‐Per‐View to Determine the World’S Greatest Martial Arts Style

Mainstream Expansion and Strategic Analysis Ram Kandasamy Victor Li David Ye Contents 1 Introduction 2 Market Analysis 2.1 Overview 2.2 Buyers 2.3 Fighters 2.4 Substitutes 2.5 Complements 3 Competitive Analysis 3.1 Entry 3.2 Strengths 3.3 Weaknesses 3.4 Competitors 4 Strategy Analysis 4.1 Response to Competitors 4.2 Gymnasiums 4.3 International Expansion 4.4 Star Promotion 4.5 National Television 5 Conclusion 6 References 1 1. Introduction The Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) started in 1993 as a mixed martial arts (MMA) tournament on pay‐per‐view to determine the world’s greatest martial arts style. Its main draw was its lack of rules. Weight classes did not exist and rounds continued until one of the competitors got knocked out or submitted to his opponent. Although the UFC initially achieved underground success, it was regarded more as a spectacle than a sport and never attained mainstream popularity. The perceived brutality of the event led to political scrutiny and pressure. Attacks from critics caused the UFC to establish a set of unified rules with greater emphasis placed on the safety. The UFC also successfully petitioned to become sanctioned by the Nevada State Athletic Commission. However, these changes occurred too late to have an impact and by 2001, the parent organization of the UFC was on the verge of bankruptcy. The brand was sold to Zuffa LLC, marking the beginning of the UFC’s dramatic rise in popularity. Over the next eight years, the UFC evolved from its underground roots into the premier organization of a rapidly growing sport.