Current Developments in Municipal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consent Decree: Safeway, Inc. (PDF)

1 2 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 4 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 5 6 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) 7 ) Plaintiff, ) Case No. 8 ) v. ) 9 ) SAFEWAY INC., ) 10 ) Defendant. ) 11 ) 12 13 14 CONSENT DECREE 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Consent Decree 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 I. JURISDICTION, VENUE, AND NOTICE .............................................................2 4 II. APPLICABILITY....................................................................................................2 5 III. OBJECTIVES ..........................................................................................................3 6 IV. DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................3 7 V. CIVIL PENALTIES.................................................................................................6 8 9 VI. COMPLIANCE REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................6 10 A. Refrigerant Compliance Management System ............................................6 11 B. Corporate-Wide Leak Rate Reduction .........................................................7 12 C. Emissions Reductions at Highest-Emission Stores......................................8 13 VII. PARTICIPATION IN RECOGNITION PROGRAMS .........................................10 14 VIII. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS .........................................................................10 15 IX. STIPULATED PENALTIES .................................................................................12 -

Western Weekly Reports

WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS Reports of Cases Decided in the Courts of Western Canada and Certain Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada 2013-VOLUME 12 (Cited [2013] 12 W.W.R.) All cases of value from the courts of Western Canada and appeals therefrom to the Supreme Court of Canada SELECTION EDITOR Walter J. Watson, B.A., LL.B. ASSOCIATE EDITORS (Alberta) E. Mirth, Q.C. (British Columbia) Darrell E. Burns, LL.B., LL.M. (Manitoba) E. Arthur Braid, Q.C. (Saskatchewan) G.L. Gerrand, Q.C. CARSWELL EDITORIAL STAFF Cheryl L. McPherson, B.A.(HONS.) Director, Primary Content Operations Audrey Wineberg, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Product Development Manager Nicole Ross, B.A., LL.B. Supervisor, Legal Writing Andrea Andrulis, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. (Acting) Supervisor, Legal Writing Andrew Pignataro, B.A.(HONS.) Content Editor WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS is published 48 times per year. Subscrip- Western Weekly Reports est publi´e 48 fois par ann´ee. L’abonnement est de tion rate $409.00 per bound volume including parts. Indexed: Carswell’s In- 409 $ par volume reli´e incluant les fascicules. Indexation: Index a` la docu- dex to Canadian Legal Literature. mentation juridique au Canada de Carswell. Editorial Offices are also located at the following address: 430 rue St. Pierre, Le bureau de la r´edaction est situ´e a` Montr´eal — 430, rue St. Pierre, Mon- Montr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. tr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. ________ ________ © 2013 Thomson Reuters Canada Limited © 2013 Thomson Reuters Canada Limit´ee NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER: All rights reserved. -

Design of a Molecular Support for Cryo-EM Structure Determination

Design of a molecular support for cryo-EM structure determination Thomas G. Martina, Tanmay A. M. Bharata,b, Andreas C. Joergera,c, Xiao-chen Baia, Florian Praetoriusd, Alan R. Fershta, Hendrik Dietzd,1, and Sjors H. W. Scheresa,1 aMedical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0QH, United Kingdom; bSir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3RE, United Kingdom; cGerman Cancer Consortium (DKTK), Institute of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; and dPhysik Department, Walter Schottky Institute, Technische Universität München, 85748 Garching near Munich, Germany Edited by Fred J. Sigworth, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved October 13, 2016 (received for review August 2, 2016) Despite the recent rapid progress in cryo-electron microscopy angles are, therefore, determined a posteriori by image-pro- (cryo-EM), there still exist ample opportunities for improvement cessing algorithms that match the experimental projection of in sample preparation. Macromolecular complexes may disassociate every individual particle with projections of a 3D model (7). or adopt nonrandom orientations against the extended air–water However, the projection-matching procedure is ultimately ham- interface that exists for a short time before the sample is frozen. We pered by radiation damage. Because the electrons that are used designed a hollow support structure using 3D DNA origami to pro- for imaging destroy the very structures of interest (see ref. 8 for a tect complexes from the detrimental effects of cryo-EM sample recent review), one needs to limit carefully the number of elec- preparation. For a first proof-of-principle, we concentrated on the trons used for imaging. -

Drb Final Resolution

COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION STANDARD SPECIFICATION SECTION 105 DISPUTE REVIEW BOARD Brannan Sand and Gravel Co. v. Colorado Department of Transportation DRB FINAL RESOLUTION BACKGROUND Colorado Project No. STA 0404-044 15821R, “Removing Asphalt Mat on West Colfax Avenue and Replacing with a new Hot Mix Asphalt Overlay”, was awarded to Brannan Sand and Gravel Company on August 11, 2008, for $1,089,047.93. The contract incorporated all Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Standard Specifications and Project Special Conditions, including, Standard Specification 109.06: Standard Specification 109.06 Partial Payments. CDOT will make partial payments to the Contractor once each month as the work progresses, when the Contractor is performing satisfactorily under the Contract. Payments will be based upon progress estimates prepared by the Engineer, of the value of work performed, materials placed in accordance with the Contract, and the value of the materials on hand in accordance with the Contract. Revision of Section 109. In September 2006, CDOT, CCA (Colorado Contractors Associations), and CAPA (Colorado Asphalt Pavement Association) formed a joint Task Force at the request of CAPA to evaluate the need for an asphalt cement cost adjustment specification that would be similar to the Fuel Cost Adjustment that was currently being used by CDOT. The result of the Task Force effort was the revision of Standard Specification 109.06 to include the Asphalt Cement Cost Adjustments Subsection. Subsection 109.06, Revision of Section 109, “Asphalt Cement Cost Adjustment When Asphalt Cement is Included in the Bid Price for HMA”, states: _____________________________________________________________ DRB Final Resolution Brannan Sand & Gravel v. -

Procedural Items for the Cmfa Summary and Recommendations ______

PROCEDURAL ITEMS FOR THE CMFA SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS _____________________________________________________________ Items: A1, A2, A3 Action: Pursuant to the by-laws and procedures of CMFA, each meeting starts with the call to order and roll call (A1) and proceeds to a review and approval of the minutes from the prior meeting (A2). After the minutes have been reviewed and approved, time is set aside to allow for comments from the public (A3). _____________________________________________________________ NEW ROADS SCHOOL SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS _____________________________________________________________ Applicant: New Roads School Action: Final Resolution Amount: $3,250,000 Purpose: Finance and Refinance the Acquisition, Construction, Improvement, Renovation and Equipping of Educational Facilities, Located in the City of Santa Monica, California. Activity: Private School Meeting: June 7, 2013 Background: New Roads School (“New Roads”) was established in 1995 as a model for education in an ethnically, racially, culturally, and socio-economically diverse community. New Roads began as a middle school program with 70 students and has grown in both directions each year thereafter. New Roads now serves over 600 students representing the kaleidoscope of communities that make up Los Angeles. Unique among independent schools, no less that 40% of the New Roads School tuition budget is devoted to need-based financial aid every year, enabling them to provide financial assistance to more than 50% of their families. Over the past 15 years, New Roads has dedicated approximately $60 million to financial aid. New Roads School seeks to spark enduring curiosity, to promote personal, social, political, cultural and moral understanding, to instill respect for the life and ecology of the earth, and to foster the sensitivity to embrace life’s deep joys and mysteries. -

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel Armed Conflicts Report Israel-Palestine (1948 - first combat deaths) Update: February 2009 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2008 The situation in the Gaza strip escalated throughout 2008 to reflect an increasing humanitarian crisis. The death toll reached approximately 1800 deaths by the end of January 2009, with increased conflict taking place after December 19th. The first six months of 2008 saw increased fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas rebels. A six month ceasefire was agreed upon in June of 2008, and the summer months saw increased factional violence between opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah. Israel shut down the border crossings between the Gaza strip and Israel and shut off fuel to the power plant mid-January 2008. The fuel was eventually turned on although blackouts occurred sporadically throughout the year. The blockade was opened periodically throughout the year to allow a minimum amount of humanitarian aid to pass through. However, for the majority of the year, the 1.5 million Gaza Strip inhabitants, including those needing medical aid, were trapped with few resources. At the end of January 2009, Israel agreed to the principles of a ceasefire proposal, but it is unknown whether or not both sides can come to agreeable terms and create long lasting peace in 2009. 2007 A November 2006 ceasefire was broken when opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah renewed fighting in April and May of 2007. In June, Hamas led a coup on the Gaza headquarters of Fatah giving them control of the Gaza Strip. -

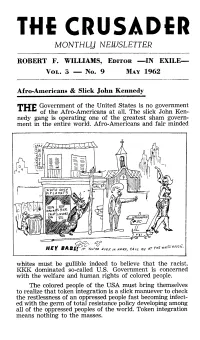

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

3/14/06 - Tuesday, March 14, 2006 EAU CLAIRE CITY COUNCIL AGENDA TUESDAY, MARCH 14, 2006 CITY HALL COUNCIL CHAMBER, 4:00 P.M. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE AND ROLL CALL CONSENT AGENDA The following matters may be acted upon by the City Council utilizing a single vote. Individual items, which any member wishes to address in greater detail or as a separate item on the regular agenda, may be removed from the Consent Agenda upon the request of any Council Member. COMMENDATIONS AND PROCLAMATIONS 1. Consideration of Commendations and Proclamations. MINUTES 2. Resolution approving Minutes of Regular Meeting of February 28, 2006. LICENSES 3. Resolution granting bartender licenses. GRANT APPLICATIONS 4. Resolution authorizing the Police Department to apply for a 2006 Bulletproof Vest Program Grant from the Wisconsin Bureau of Justice Assistance. 5. Resolution authorizing the Police Department to apply for a Pedestrian Safety Enforcement Project Grant through the Wisconsin Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Safety. 6. Resolution authorizing the Police Department to apply for a Click It or Ticket Mobilization Grant through the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Safety. 7. Resolution authorizing the Fire Department to apply for FIRE Act monies from the Department of Homeland Security to purchase water rescue equipment. TREE REMOVAL 8. Final Resolution granting petition and waivers for tree removal at five locations beginning with 1616 Rust Street, Parcel No. 03-0405. PRELIMINARY RESOLUTION - STREET, UTILITY & SIDEWALK IMPROVEMENTS 9. Preliminary Resolution declaring the City's intention to exercise its special assessment powers under Section 66.0703, Wisconsin Statutes, for street improvements on Truax Boulevard, N. -

Official Proceedings of the Meetings of the Board Of

OFFICIAL PROCEEDINGS OF THE MEETINGS OF THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF PORTAGE COUNTY, WISCONSIN January 18, 2005 February 15, 2005 March 15, 2005 April 19, 2005 May 17, 2005 June 29, 2005 July 19, 2005 August 16,2005 September 21,2005 October 18, 2005 November 8, 2005 December 20, 2005 O. Philip Idsvoog, Chair Richard Purcell, First Vice-Chair Dwight Stevens, Second Vice-Chair Roger Wrycza, County Clerk ATTACHED IS THE PORTAGE COUNTY BOARD PROCEEDINGS FOR 2005 WHICH INCLUDE MINUTES AND RESOLUTIONS ATTACHMENTS THAT ARE LISTED FOR RESOLUTIONS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE COUNTY CLERK’S OFFICE RESOLUTION NO RESOLUTION TITLE JANUARY 18, 2005 77-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, CRUEGER PROPERTY 78-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, TURNER PROPERTY 79-2004-2006 HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES NEW POSITION REQUEST FOR 2005-NON TAX LEVY FUNDED-PUBLIC HEALTH PLANNER (ADDITIONAL 20 HOURS/WEEK) 80-2004-2006 DIRECT LEGISLATION REFERENDUM ON CREATING THE OFFICE OF COUNTY EXECUTIVE 81-2004-2006 ADVISORY REFERENDUM QUESTIONS DEALING WITH FULL STATE FUNDING FOR MANDATED STATE PROGRAMS REQUESTED BY WISCONSIN COUNTIES ASSOCIATION 82-2004-2006 SUBCOMMITTEE TO REVIEW AMBULANCE SERVICE AMENDED AGREEMENT ISSUES 83-2004-2006 MANAGEMENT REVIEW PROCESS TO IDENTIFY THE FUTURE DIRECTION TECHNICAL FOR THE MANAGEMENT AND SUPERVISION OF PORTAGE COUNTY AMENDMENT GOVERNMENT 84-2004-2006 FINAL RESOLUTION FEBRUARY 15, 2005 85-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, WANTA PROPERTY 86-2004-2006 AUTHORIZING, APPROVING AND RATIFYING A SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT INCLUDING GROUND -

Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court Of

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com AT 15' Fl LEMUEL SHAW I EMUEL SHAW CHIFF jl STIC h OF THE SUPREME Jli>I«'RL <.OlRT OF MAS Wlf .SfcTTb i a 30- 1 {'('• o BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY tHASH BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 1 9 1 8 LEMUEL SHAW CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT OF MASSACHUSETTS 1830-1860 BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (Sbe Slibttfibe $rrtf Cambribgc 1918 COPYRIGHT, I9lS, BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published March iqiS 279304 PREFACE It is doubtful if the country has ever seen a more brilliant group of lawyers than was found in Boston during the first half of the last century. None but a man of grand proportions could have emerged into prominence to stand with them. Webster, Choate, Story, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jeremiah Mason, the Hoars, Dana, Otis, and Caleb Cushing were among them. Of the lives and careers of all of these, full and adequate records have been written. But of him who was first their associate, and later their judge, the greatest legal figure of them all, only meagre accounts survive. It is in the hope of sup plying this deficiency, to some extent, that the following pages are presented. It may be thought that too great space has been given to a description of Shaw's forbears and early surroundings; but it is suggested that much in his character and later life is thus explained. -

Former Westfield HS Teacher Accused of Sexual Advances Todisco

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, June 7, 2018 OUR 128th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 23-2018 Periodical – Postage Paid at Rahway, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] ONE DOLLAR Former Westfield HS Teacher Accused of Sexual Advances By LAUREN S. BARR the Telluride website. to public Facebook posts that have Specially Written for The Westfield Leader More than a dozen people told The since been removed from public view WESTFIELD – At least three Westfield Leader that they had heard by two other women, identified as women have come forward to say that rumors about Mr. Silbergeld being A.M. and M.O., who were WHS gradu- former Westfield High School (WHS) romantically involved with students ates from the classes of ’02 and ’04. English teacher Marc Silbergeld en- during his time at WHS, but none of The posts called Mr. Silbergeld out as gaged in inappropriate behavior with them knew any specific information. a “predator” and pleaded for more them while they were his students. Last fall The Westfield Leader was women to come forward. Mr. Silbergeld is a 1987 graduate of contacted by Zoe Kaidariades, WHS M.O.’s post stated that she has e- WHS who graduated from the Univer- ’05, who, after watching the news cov- mails from Mr. Silbergeld where he sity of Michigan and returned to teach erage and witnessing the #MeToo admitted to his behavior and he admits from 1996 to 2013. He also served as movement unfurl, felt the need to come that his actions were wrong.