View Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

24 August 2021

24 August 2021 12:01 AM Bruno Bjelinski (1909-1992) Concerto da primavera (1978) Tonko Ninic (violin), Zagreb Soloists HRHRTR 12:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Piano Sonata in C major K.545 Young-Lan Han (piano) KRKBS 12:21 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 3 Songs for chorus, Op 42 Danish National Radio Choir, Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 12:32 AM Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824) Serenade for 2 violins in A major, Op 23 no 1 Angel Stankov (violin), Yossif Radionov (violin) BGBNR 12:41 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809),Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757-1831), Harold Perry (arranger) Divertimento 'Feldpartita' in B flat major, Hob.2.46 Academic Wind Quintet BGBNR 12:50 AM Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) Seguida Espanola Henry-David Varema (cello), Heiki Matlik (guitar) EEER 12:59 AM Toivo Kuula (1883-1918) 3 Satukuvaa (Fairy-tale pictures) for piano (Op.19) Juhani Lagerspetz (piano) FIYLE 01:15 AM Edmund Rubbra (1901-1986) Trio in one movement, Op 68 Hertz Trio CACBC 01:35 AM Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Peer Gynt - Suite No 1 Op 46 Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Ole Kristian Ruud (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:28 AM Max Bruch (1838-1920) Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26 James Ehnes (violin), Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, Giordano Bellincampi (conductor) NZRNZ 02:52 AM Eugene Ysaye (1858-1931) Sonata for Solo Violin in D minor, op. 27/3 James Ehnes (violin) NZRNZ 02:59 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Symphony No. -

"If There Were More Cynthia Phelpses Around, There Might Be More Viola Recitals…She Is a Master of Her Instrument -- Rema

"If there were more Cynthia Phelpses around, there might be more viola recitals…she is a master of her instrument -- remarkable technique and warm, full sound." – THE WALL STREET JOURNAL "Not only does CYNTHIA PHELPS produce one of the richest, deepest viola timbres in the world, she is a superb musician" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). Principal Violist of the New York Philharmonic, Ms. Phelps has distinguished herself both here and abroad as one of the leading instrumentalists of our time. The recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the Pro Musicis International Award and first prize at both the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition and the Washington International String Competition, she has captivated audiences with her compelling solo and chamber music performances. She is "a performer of top rank...the sounds she drew were not only completely unproblematical --technically faultless, generously nuanced-- but sensuously breathtaking" (The Boston Globe). Ms. Phelps performs throughout the world as soloist with orchestras, including the Minnesota Orchestra, Shanghai, San Diego, Santa Barbara, Eastern Music Festival and Vermont Symphonies, Orquesta Sinfonica de Bilbao, and Rochester and Hong Kong Philharmonic among others. World-wide, her electrifying solo appearances with the New York Philharmonic garner raves; they have included Berlioz's Harold in Italy, the Bartok Viola Concerto, Strauss's Don Quixote, the Benjamin Lees Concerto for String Quartet, the premiere of a concerto written for her by Sofia Gubaidulina and most recently, the premiere of a new concerto by the young composer Julia Adolphe written for her. She has appeared as soloist with the orchestra across the globe, including Vienna’s Musikverein, London’s Royal Festival Hall, and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam among others. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Music Director Stéphane Denève Announce Fall Programming for the 2021/2022 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [June , ] Contacts: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra: Eric Dundon [email protected], C'D-*FG-D'CD National/International: NiKKi Scandalios [email protected], L(D-CD(-D(MD THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA AND MUSIC DIRECTOR STÉPHANE DENÈVE ANNOUNCE FALL PROGRAMMING FOR THE 2021/2022 SEASON Highlights of offerings from September 17-December 5, 2021, include: • The return of full orchestral performances led by Music Director Stéphane Denève at Powell Hall featuring repertoire spanning genre and time that celebrates the resilience of the human spirit. • Denève opens the classical season with two programs at Powell Hall. The season opener includes the first SLSO performances of Jessie Montgomery’s Banner and Anna Clyne’s Dance alongside Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4. In his second weeK, Denève leads the SLSO in the string orchestra version of Caroline Shaw’s Entr’acte, Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question, Christopher Rouse’s Rapture, and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with pianist Yefim Bronfman. • The SLSO and Denève continue their deep commitment to music and composers of today, performing works by Thomas Adès, Karim Al-Zand, William Bolcom, Jake Heggie, James Lee III, Jessie Montgomery, Caroline Shaw, Carlos Simon, Outi Tarkiainen, Joan Tower, and the U.S. premiere of Anna Clyne’s PIVOT. • Other highlights of Denève’s fall programs include performances of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Dmitri ShostaKovich’s Symphony No. 5, and collaborations with pianist VíKingur Ólafsson in his first SLSO appearance and violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider. • The highly anticipated return of the free Forest Park concert, which welcomes thousands of St. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Chamber Music Handbook 2019–20 2 Office Staff

INSTRUMENTAL CHAMBER MUSIC HANDBOOK 2019–20 2 OFFICE STAFF David Geber, Artistic Advisor to Chamber Music Katharine Dryden, Managing Director of Instrumental Ensembles [email protected] 917 493-4547 Office: Room 211 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 Who is required to take chamber music? 5 Semester overview 6 Chamber music class policies 7 Beginning-of-semester checklist 9 End-of-semester checklist 10 How to make future group requests 11 Chamber music competitions at MSM 13 Chamber music calendar for 2019-20 14 Chamber music faculty 17 Table of chamber music credit requirements 18 3 INTRODUCTION Chamber music is a vital part of study and performance at Manhattan School of Music. Almost every classical instrumentalist is required to take part in chamber music at some point in each degree program. Over 100 chamber ensembles of varying size and instrumentation are formed each semester. The chamber music faculty includes many of the School’s most experienced chamber musicians, including current or former members of the American, Brentano, Juilliard, Mendelssohn, Orion and Tokyo string quartets, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, among others. Our resident ensembles, American String Quartet and Windscape, also coach and give seasonal performances. Masterclasses given by distinguished artists are available to chamber groups by audition or nomination from the chamber music faculty. In addition to more traditional ensembles, Baroque Aria Ensemble is offered in fulfillment of one semester of instrumental chamber music. Pianists may earn chamber music credit from participation in standard chamber groups or two-piano teams. Other options for pianists include participation in the following chamber music classes: the Instrumental Accompanying Class (IAC), vocal accompanying classes including Russian Romances and Ballads and Songs of the Romantic Period, and Approaches to Chamber Music for Piano and Strings. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

Chamber Music Festival of Lexington Merges with Lexington Chamber Orchestra Distinct Offerings and Programs Will Continue Under Shared Governance and Administration

PRESS RELEASE - For Immediate Release Contact: Gregory Pettit – President [email protected] | 917-450-6267 Chamber Music Festival of Lexington Merges with Lexington Chamber Orchestra Distinct Offerings and Programs will Continue Under Shared Governance and Administration May 21, 2019- LEXINGTON, KY – The Chamber Music Festival of Lexington and the Lexington Chamber Orchestra today announced the merger of the two non-profit performing arts organizations that serve Lexington and Cen- tral Kentucky. Going forward, both organizations will be governed by a new Board of Directors comprising exist- ing Chamber Festival board members and musicians of the Chamber Festival of Lexington. Both organizations will continue to operate as two distinct performing arts organizations with their own seasons, musicians and artistic direction, but with shared governance, management and with a common 501(c)(3) designation. Nathan Cole and Jan Pellant will continue their roles as musical directors of the Chamber Music Festival of Lexington and of the Lexington Chamber Orchestra, respectively. Gregory Pettit, President of the Chamber Music Festival of Lexington, observed, “These two organizations have distinct brands and roles in our musical community. For over a dozen years, The Chamber Music Festival of Lex- ington has brought world class musicians to the Bluegrass for 10 days in August for formal concerts and infor- mal, free performances for the public and thousands of schoolchildren. The Lexington Chamber Orchestra has for the last four years produced a year-round season performed by local musicians, with a “name your ticket price” admissions policy. They will both continue their respective seasons as before. However, we share a commitment to excellence and accessibility for the chamber music genre. -

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

CONCERT #5 - Released February 17, 2021 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Sonata No. 6 for Violin and Piano in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1 Allegro Adagio molto espressivo Allegretto con variazioni Amy Schwartz Moretti violin / Orion Weiss piano WOLFgang AMADEUS MOZART Quartet for Piano and Strings in G minor, K. 478 Allegro Andante Rondo Benjamin Bowman violin /Jonathan Vinocour viola / Edward Arron cello / Jeewon Park piano LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN frequently alternates between excited episodes and (1770-1827) moments of quiet reflection. The main theme is built Sonata No. 6 for Violin and Piano in A Major, from a series of rising intervals. A brief coda ends it Op. 30, No. 1 (1802) peacefully. Most recent SCMS performance: Summer 2011 In triple meter the Adagio, molto espressivo opens Enjoying early fame as both pianist and composer, with a floating violin line over gently coaxing the year 1802 threatened Beethoven’s prospects for rhythmic thrusts on the piano. As if to stress the ongoing success. Attempts to secure a court position importance of the violin the piano supports the failed to materialize. Worst of all, his deepening bowed instrument’s expressive long-breathed deafness and attendant despair began to isolate him melodies with understated prodding alternating from the world around him. with simple arpeggios. It is the piano, however, that has the final, albeit softly spoken, word at the In October came his famous lament, the movement’s end. Heiligenstadt Testament, a letter he wrote but never sent to his brothers wherein he expressed In its initial form, Beethoven provided an energetic his terrible anguish and doubt, and admitted to and virtuosic finale before replacing it with an thoughts of suicide. -

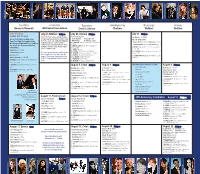

Calendarmailerfinal:Layout 1

Jon Manasse Boston Cello Quartet Julian Schwarz Jon Nakamatsu Martin Beaver Amit Peled Cypress String Quartet Stephanie Chase Yeesun Kim Curtis on Tour Emerson String Quartet Natasha Paremski Noreen Polera Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Dennis & Yarmouth Wellfleet & Provincetown Cotuit & Orleans Chatham Wellfleet Wellfleet Cape Cod Gala July 21, Wellfleet 7:30pm July 29, Orleans 7:30pm July 31 7:30pm Sunday, July 27 ~ 6pm Curtis On Tour features a string chamber Boston Cello Quartet Jon Manasse, CLARINET Blaise Déjardin Adam Esbensen Join us for a festive evening at our orchestra performing Antonio Vivaldi’s iconic Emerson String Quartet Cape Cod Gala! Featuring music by The Four Seasons paired with Ástor Piazzolla’s Mihail Jojatu Alexandre Lecarme tango masterpieces Cuatro Estaciones W.A. MOZART Overture to The Abduction from the Eugene Drucker, VIOLIN Philip Setzer, VIOLIN the Manasse/Nakamatsu Duo. Cocktails Seraglio Porteñas (The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires) Lawrence Dutton, VIOLA Paul Watkins, CELLO at 6, music at 6:45 followed by a full F. MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from A Midsummer buffet dinner. featuring celebrated Curtis alumna violinist Night’s Dream J. HAYDN String Quartet in G Minor; Opus 20 No. Elissa Lee Koljonen (’94). C. DEBUSSY Reverie 3, Hob. III.33 Jon Manasse, CLARINET D. POPPER Suite for Two Cellos, Opus 16 W. A. MOZART Quintet in A Major for Clarinet and The proceeds from this concert will help fund Jon Nakamatsu, PIANO E. CHABRIER España, rapsodie pour orchestra Strings, K. 581 Luis Ortiz, PIANO the restoration of the late 18th-early 19th J. WILLIAMS Theme from Angela’s Ashes century “Church Bass” that has been in the L. -

Artist Series: David Shifrin Program Notes on the Program

ARTIST SERIES: DAVID SHIFRIN PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Quintet in A major for Clarinet, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, K. 581 (1789) Allegro Larghetto Menuetto Allegretto con variazioni David Shifrin, clarinet • Danbi Um, violin • Bella Hristova, violin • Mark Holloway, viola • Dmitri Atapine, cello LUIGI BASSI (1833-1871) Concert Fantasia on Themes from Verdi’s Rigoletto for Clarinet and Piano David Shifrin, clarinet • Gloria Chien, piano DUKE ELLINGTON (1899-1974) Clarinet Lament for Clarinet and Piano (1936) (arr. David Schiff) David Shifrin, clarinet • Gloria Chien, piano NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Quintet in A major for Clarinet, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, K. 581 (1789) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Salzburg, 1756 – Vienna, 1791) Mozart wrote this quintet for Vienna’s Society of Musicians (Tonkünstler-Societät) in 1789. The society raised money to provide pensions to widows and orphans of Viennese musicians. Its concerts were regular occurrences on the Viennese social calendar and Mozart composed and performed for them, even though he was not a member, something he would regret right before his death at the age of 35. This quintet premiered at a society concert on December 22, 1789, in between two halves of a cantata by Vincenzo Righini. The clarinetist was Anton Stadler, one of the first virtuosos on the instrument and Mozart’s close personal friend. Mozart wrote all of his major clarinet works— this one, the Kegelstatt Trio, and the Clarinet Concerto—with Stadler’s playing in mind. Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center The clarinet was a relatively new instrument in Mozart’s day yet he expertly tapped into the instrument’s unique singing quality.