The Civic Plunge Revisited March 24Th 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

Municipal Clerks and Phone Numbers

MUNICIPAL CLERKS/ADMINISTRATORS MUNICIPALITY NAME PHONE ADDRESS: HOME and/or HALL * NMD (No Mail Delivery) Town of Bangor Louisa Peterson 608-461-0554 W1250 County Rd U, Bangor WI 54614 (home) Town of Barre Ann Schlimgen 608-786-4382 N3290 Russlan Coulee Rd, La Crosse WI (home) 54601 (home) W3541 County Rd M, La Crosse WI 54601 (hall) Town of Burns Melissa Hart- 608-385-5436 W2295 E. Olson Rd, Bangor WI 54614 Pollock (home) 608-486-4272 W1313 Jewett Rd, Bangor WI 54614 (hall) (hall) Town of Cassie Hanan 608-783-0050 2219 Bainbridge St, La Crosse WI 54603 Campbell (hall) Town Hall Hours (M-F: 8-5) Town of Crystal Sbraggia 608-780-4778 PO Box 115 Mindoro, WI 54644 Farmington (cell) 608-857-3913 N8309 State Rd 108, Mindoro WI * NMD (hall) Town of Jill Murphy 608-787-0400 N1800 Town Hall Rd, La Crosse WI 54601 Greenfield (hall) (hall) 608-769-4138 (cell) Town of Sara Schultz 608-786-1516 W3501 Pleasant Valley Rd, West Salem WI Hamilton (home) 54669 608-786-0989 (hall) N5105 N Leonard St, West Salem WI 54669 (hall) Town of Marilyn Pedretti 608-526-3354 W7937 County Rd MH, Holmen WI 54636 Holland (hall) 608-317-9698 Town Hall Hours (M & Th: 8-1, W: 3-6) (cell) Town of Diane Elsen 608-781-2275 N3393 Smith Valley Rd, La Crosse WI 54601 Medary (hall) Town Hall Hours (T 8-11; Th 3-6; Fri 8-11) Town of Mary Rinehart 608-783-4958 N5589 Commerce Rd, Onalaska WI 54650 Onalaska (hall) Town Hall Hours (M-Th 8-12; 1-5; F 8-12) Town of Shelby Fortune Weaver 608-788-1032 2800 Ward Ave, La Crosse WI 54601 (hall) Town Hall Hours(M-F: 8-4) Town of Barb 608-486-2297 -

Barking and Dagenham Is Supporting Our Children and Young People Like

this Barking and Dagenham Working with a range of is supporting our children organisations, we’re running and young people like exciting FREE holiday clubs never before! for children and young people right across the borough who are eligible. To find out more about each programme, and to book your place, visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/free-summer-activities. Each activity includes a healthy lunch. For free activities in the borough for all families visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/newme-healthy-lifestyle This provision is funded through the Department for Education’s Holiday Activities and Food Programme. #HAF2021. Take part in a summer to remember for Barking and Dagenham! Location Venue Dates Age Group 8 to 11 years IG11 7LX Everyone Active at Abbey Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years 4 to 7 years RM10 7FH Everyone Active at Becontree Heath Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 8 to 11 years 12 to 16 years 8 to 11 years RM8 2JR Everyone Active at Jim Peters Stadium Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years IG11 8PY Al Madina Summer Fun Programme at Al Madina Mosque Monday 2 August to Thursday 26 August 5 to 12 years RM8 3AR Ballerz at Valence Primary School Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 5 to 11 years RM8 2UT Subwize at The Vibe Tuesday 3 August to Saturday 28 August 7 to 16 years Under 16 RM10 9SA Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Park Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 6 August years Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Greatfields Under 16 IG11 0HZ Monday 9 August to Friday 20 -

ISDS Vol 2 Descriptive Document

Hornsey Town Hall ISDS Volume 2 Descriptive Document November 2015 │ Hornsey Town Hall | ISDS Vol 2 Descriptive Document Contents Foreword _________________________________________________________ 04 Introduction ______________________________________________________ 06 Context __________________________________________________________ 08 Background ______________________________________________________ 09 The site ___________________________________________________________ 10 The development context _________________________________________ 12 The opportunity ___________________________________________________ 14 The proposed delivery structure ____________________________________ 15 Key development deliverables ____________________________________ 16 Timetable and process ____________________________________________ 18 Appendices Red line plan _______________________________________________________ I Schedule of community groups _____________________________________ II 3 Foreword Hornsey Town Hall is one of north London’s most iconic landmarks. Sitting in the heart of Haringey’s vibrant Crouch End, the fabulous art deco building is steeped in local history – having served as the civic heart of the former borough of Hornsey and played a leading role as a much-loved arts and culture hub. Opened in 1935 and built to designs by renowned architect RH Uren, Hornsey Town Hall was given its much-deserved Grade II* listed status in 1981. This is a building rich in architectural heritage, boasting a wealth of intricate period features. It is -

Dirección General De Bibliotecas, Archivos Y Museos

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS DEPARTAMENTO DE PATRIMONIO BIBLIOGRÁFICO Y DOCUMENTAL ARCHIVO DE VILLA THE ARCHIVO DE VILLA (TOWN ARCHIVE) OF MADRID The Archivo de Villa of Madrid contains, throughout its more than 18,500 running metres of shelves, documents created and received at the Madrid City Council since 1152. This archive was first mentioned in a Royal Provision of Charles V –Charles I of the Spanish empire– (1525), although the so-called 'ark of the three keys', a medieval deposit for the parchments of Madrid, is repeatedly mentioned in the books of resolutions since the 15th century. The Archive was finally set up in the 18th century. In 1748, the first professional archivist was appointed. The first regulations and operation instructions for the archive were approved in 1753 and it became a "Public Office" with the right to issue official certificates by virtue of a Royal Decree in 1781. This Institution was opened for research in 1844. It has changed its headquarters several times: Tower of the San Salvador church and Monastery of Santo Domingo (15th to 17th century), First Town Hall of Madrid (17th century-1868), Second Town Hall “Casa Panadería” in Plaza Mayor (1868-1987), Conde Duque barracks (1987-), but the custody of the materials it contains was never interrupted, not even during the Peninsular War (1808-1814), or during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). COLLECTIONS Except for two small acquisitions of private archives, the collections come from the Madrid City Council itself and from the City Councils that were annexed to Madrid during the fifties, in the past century. -

Baxters Conservation Plan 2004

HORNSEY TOWN HALL CONSERVATION PLAN Prepared for LONDON BOROUGH OF HARINGEY ALAN BAXTER & ASSOCIATES JANUARY 2004 CONTENTS CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction and Summary Findings ................................................... 2 2.0 Heritage Designations ........................................................................ 7 3.0 Understanding ................................................................................. 11 4.0 The Cultural Significance of the Town Hall and Associated Buildings .................................................................. 45 5.0 Issues and Opportunities .................................................................. 50 6.0 Policies and Guiding Principles for the Reuse of the Town Hall ........ 55 7.0 Sources ............................................................................................ 61 Appendices Appendix 1: Listed Building Descriptions .............................................. 62 Appendix 2: Crouch End and Hornsey Conservation Area Policy Document .................................. 64 Appendix 3: Extracts from Urban Design Study (2003) by Jon Rowland Urban Design ............................................... 67 Prepared by: Chris Miele, Catharine Kidd & Zoë Aspinall Reviewed by: Alan Baxter and William Filmer-Sankey First Draft issued: 18 November 2003 Consultation Draft issued: 24 November 2003 Second Draft issued: 10 December 2003 Conservation Plan issued: 28 January 2004 This report is the copyright of Alan Baxter & Associates and is for the sole use of the person/organisation -

Older People's Week 2019 Monday 30 September to Friday 4 October

Tweet your pics using #LBBDOPW #LBBDOPW Young at Heart Young at Heart 3 9 74 Older People’s Week 2019 Monday 30 September to Friday 4 October MC8700 SEP19 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Barking and Dagenham Council along with partners from across the borough are hosting a week of events for Older People’s Week running from 30 September to 4 October to celebrate our older residents and the contribution they make to our community. This year, we are celebrating the theme ‘The Journey to Age Equality’ and all the events have Older People’s Week 2019 been designed to encourage people of all ages to get together, have fun and age well. Date Activity Venue Time Event contact Monday Movie Showcase – Come along for a fun film screening of ‘The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel’. Pick a seat and enjoy! Barking Learning Centre Conference 4.30pm to 7pm Pennu Charity 07825 637097 30 September Centre, Barking, IG11 7NB Tuesday Dementia Friends Training Sessions – Training sessions for professionals including health and care providers. Learn more about Dementia by becoming BLC Conference Centre, Barking, 2 sessions – 12pm to 1pm Alzheimers Society - 020 8227 2828 1 October a Dementia Friend. Booking required. IG11 7NB and 1pm to 2pm [email protected] Close Encounters’ – Enjoy a Heritage exhibition at Valence House Museum where you will be able to touch and handle the artefacts of the borough. Valence House, Dagenham, RM8 3HT 2pm to 4pm LBBD Heritage Service - 020 8227 2034 [email protected] Young at Heart – Join us at Kingsley Hall for a celebration with a showcase of activities, groups and classes available for residents in the borough. -

Appendix 4 – Internal Consultees

APPENDIX 4 – INTERNAL CONSULTEES INTERNAL COMMENT OFFICER CONSULTEE RESPONSE LBH Waste Further to your request concerning the above planning application I have the following comments to make: Comments Management Noted. Waste - Wheelie bins or bulk waste containers must be provided for household issues are collections. addressed in - Bulk waste containers must be located no further than 10 metres from the point of collection. Section 6 of - Route from waste storage points to collection point must be as straight as possible with no kerbs or the report. steps. Gradients should be no greater than 1:20 and surfaces should be smooth and sound, concrete rather than flexible. Dropped kerbs should be installed as necessary. - If waste containers are housed, housings must be big enough to fit as many containers as are necessary to facilitate once per week collection and be high enough for lids to be open and closed where lidded containers are installed. Internal housing layouts must allow all containers to be accessed by users. Applicants can seek further advice about housings from Waste Management if required. - Waste container housings may need to be lit so as to be safe for residents and collectors to use and service during darkness hours. - All doors and pathways need to be 200mm wider than any bins that are required to pass through or over them. - If access through security gates/doors is required for household waste collection, codes, keys, transponders or any other type of access equipment must be provided to the council. No charges will be accepted by the council for equipment required to gain access. -

The Design of New Buildings in Historical Urban Context: Formal Interpretation As a Way of Transforming Architectural Elements of the Past

THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ELİF BEKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE SEPTEMBER 2018 Approval of the thesis: THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST submitted by ELİF BEKAR in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar _________________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Cânâ Bilsel _________________ Head of Department, Architecture Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Supervisor, Architecture Dept., METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc.Prof. Dr. Haluk Zelef _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Esin Boyacıoğlu _________________ Department of Architecture, Gazi University Date: 07.09.2018 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Elif Bekar Signature : ____________________ iv ABSTRACT THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST Bekar, Elif M.Arch., Department of Architecture Supervisor: Prof. -

Moving to Secondary School Information for Parents About Children Moving to Secondary-Phase Schools in 2019

Education Information for parents about children moving to secondary-phase schools in 2019 Moving to Secondary School Information for parents about children moving to secondary-phase schools in 2019 2 2 The closing date for all If your child was born between applications is 1 September 2007 and 31 August 2008, 31 October they will be moving to a secondary-phase school in 2018 September 2019. This move is not an automatic process and you will need to apply for the secondary-phase schools you would like your child to go to. If you would like information about applying for a place at secondary-phase school, please come to our information meeting. Speeches begin at 7pm and admission officers will be available afterwards to answer any questions you may have about the admissions process. We look forward to seeing you at 7pm on 11 September 2018 at the Broadway Theatre in Barking. Need help to apply online? Help sessions are available at Dagenham Library on Tuesdays and Barking Learning Centreon Thursdays from 11 September until 30 October 2018. Each session starts at 9am and ends at 4.30pm. Apply If you try to apply online and you cannot see your exact address in the list presented, or theschools you want to apply for are not listed, you must contact the School Admissions Team by 5pm on 31 October 2018. The closing date for your online application and the other information we ask for is 31 October 2018 Apply online for a secondary-phase school place now: www.lbbd.gov.uk/admissions Apply online for a secondary-phase school place: www.lbbd.gov.uk/admissions Introduction Moving from primary or junior To apply, you must use the Applications we receive after school to secondary-phase school common application form provided this date are late, and we will not is not an automatic process and by the borough you live in. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13Ra FEBRUARY 1959 1081

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13ra FEBRUARY 1959 1081 Government, Whitehall, London S.W.I, object to the thence northwards and northwestwards along .the confirmation of the Order. centre of North Road, North Hill and Great North Road to the borough boundary. SCHEDULE (NOTE. The area includes all properties: That part of the Metropolitan Borough of Hammer- (a) In Bishopswood Road, Broadlands Road smith comprising Angel Walk, Aspen Gardens, Blacks Compton Avenue, Courtenay Avenue, Denewood Road, Bridge Avenue (including Bridge Avenue Road, Gaskell Road, Grange Road, Kenwood Road, Mansions), Bridge View, Butterwick, Butterswick North Grove, Sheldon Avenue, Storey Road, Cottages, Colet Gardens, Chancellors Road (even Stormont Road, View Road and Yeatman Road; numbers), Chancellors Street, Crisp Road, Down (b) In those parts of Aylmer Road, Bancroft Place, Edith Road (Nos. 2 to 20 even), Elric Street, Avenue, Hampstead Lane and The Grove, and of Foreman Court, Fulham Palace Road (Nos. 1 to 89 the south-west side of Great North Road which odd—"Nos 14 to 66 even) (including Guinness Build- are within the Borough of Hornsey ; and ings and Peabody Estate), Great West Road (from (c) On the west side of North Road and the Eastern Borough Boundary to Nigel Playfair Avenue), south-west side of North Hill.) Hammersmith Bridge Road (including Digby Man- sions), Hammersmith Broadway (Nos. 1 to 30 odd), Dated this 13th day of February 1959. Hammersmith Road (Nos. 157 to 267 odd), Holcombe H. Bedale, Town Clerk. Street, King Street (Nos. 1 to 191 odd), 'Lower Mall, Town Hall, Lurgan Street, Macbeth Street, Mall Road, Mall Crouch End, London N.8. -

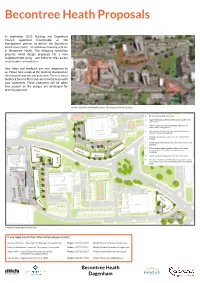

Becontree Heath Proposals

Becontree Heath Proposals In September 2015, Barking and Dagenham Council appointed Countryside as the development partner to deliver the Becontree Heath masterplan - an ambitious housing scheme in Becontree Heath. The following exhibition presents initial design proposals for a new neighbourhood along and Althorne Way across several under-utilised sites. Your ideas and feedback are very important to us. Please take a look at the material displayed on these boards and ask any questions. There is also a feedback form to fll in and return to the team with your comments. These comments will be taken into account as the designs are developed for planning approval. Aerial view of the existing Becontree Heath area showing the sites. 1. Terrace houses line the street. 2. Apartment blocks defne street corners and frame open space. 3. Mews streets are well overlooked with second ‘front doors’ into gardens. 4. The existing pharmacy is relocated on the ground 6 foor of the apartment block. 5. Communal amenity space is secure and well over looked. 6. Landscaped parking areas are retained to serve local demand 4 8 2 7. The style and colour palette of the Civic Centre Block A Block C1 3 are echoed in the architecture of the new buildings. Block D Block C2 Block B 8. Landscaped parking areas serve the new homes. 1 9. A new bus terminus will be built in the leisure centre 5 car park to replace the existing bus facility on Wood Lane. 8 Replacement Bus Terminus (Indicative Layout) 7 8 Block G1 1 3 9 Block E Block G2 5 2 8 Block F 6 Car Park Proposed landscaped masterplan If you need any further information please contact: Sheean McKeever - Development Manager at Countryside Phone: 01277 237 952 Email: [email protected] Mahbub Khandoker - Associate Director at Countryside Phone: 01277 237 951 Email: [email protected] Angela Wint - Senior Project Manager at Newlon Phone: 020 7613 6897 Email: [email protected] (affordable housing provider) Alex Jeremy - Regeneration Offcer at LBBD Phone: 020 8227 5243 Email: [email protected] Becontree Heath Dagenham.