On an Argument of David Deutsch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0010 147..160 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 147–160 Object Oriented Ontology and Its Critics Simon Weir* Living and Nonliving Occasionalism https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0010 received November 05, 2019; accepted February 14, 2020 Abstract: Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology has employed a variant of occasionalist causation since 2002, with sensual objects acting as the mediators of causation between real objects. While the mechanism for living beings creating sensual objects is clear, how nonliving objects generate sensual objects is not. This essay sets out an interpretation of occasionalism where the mediating agency of nonliving contact is the virtual particles of nominally empty space. Since living, conscious, real objects need to hold sensual objects as sub-components, but nonliving objects do not, this leads to an explanation of why consciousness, in Object-Oriented Ontology, might be described as doubly withdrawn: a sensual sub-component of a withdrawn real object. Keywords: Graham Harman, ontology, objects, Timothy Morton, vicarious, screening, virtual particle, consciousness 1 Introduction When approaching Graham Harman’s fourfold ontology, it is relatively easy to understand the first steps if you begin from an anthropocentric position of naive realism: there are real objects that have their real qualities. Then apart from real objects are the objects of our perception, which Harman calls sensual objects, which are reduced distortions or caricatures of the real objects we perceive; and these sensual objects have their own sensual qualities. It is common sense that when we perceive a steaming espresso, for example, that we, as the perceivers, create the image of that espresso in our minds – this image being what Harman calls a sensual object – and that we supply the energy to produce this sensual object. -

A Simple Proof That the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics Is Inconsistent

A simple proof that the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is inconsistent Shan Gao Research Center for Philosophy of Science and Technology, Shanxi University, Taiyuan 030006, P. R. China E-mail: [email protected]. December 25, 2018 Abstract The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is based on three key assumptions: (1) the completeness of the physical description by means of the wave function, (2) the linearity of the dynamics for the wave function, and (3) multiplicity. In this paper, I argue that the combination of these assumptions may lead to a contradiction. In order to avoid the contradiction, we must drop one of these key assumptions. The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics (MWI) assumes that the wave function of a physical system is a complete description of the system, and the wave function always evolves in accord with the linear Schr¨odingerequation. In order to solve the measurement problem, MWI further assumes that after a measurement with many possible results there appear many equally real worlds, in each of which there is a measuring device which obtains a definite result (Everett, 1957; DeWitt and Graham, 1973; Barrett, 1999; Wallace, 2012; Vaidman, 2014). In this paper, I will argue that MWI may give contradictory predictions for certain unitary time evolution. Consider a simple measurement situation, in which a measuring device M interacts with a measured system S. When the state of S is j0iS, the state of M does not change after the interaction: j0iS jreadyiM ! j0iS jreadyiM : (1) When the state of S is j1iS, the state of M changes and it obtains a mea- surement result: j1iS jreadyiM ! j1iS j1iM : (2) 1 The interaction can be represented by a unitary time evolution operator, U. -

Abstract for Non Ideal Measurements by David Albert (Philosophy, Columbia) and Barry Loewer (Philosophy, Rutgers)

Abstract for Non Ideal Measurements by David Albert (Philosophy, Columbia) and Barry Loewer (Philosophy, Rutgers) We have previously objected to "modal interpretations" of quantum theory by showing that these interpretations do not solve the measurement problem since they do not assign outcomes to non_ideal measurements. Bub and Healey replied to our objection by offering alternative accounts of non_ideal measurements. In this paper we argue first, that our account of non_ideal measurements is correct and second, that even if it is not it is very likely that interactions which we called non_ideal measurements actually occur and that such interactions possess outcomes. A defense of of the modal interpretation would either have to assign outcomes to these interactions, show that they don't have outcomes, or show that in fact they do not occur in nature. Bub and Healey show none of these. Key words: Foundations of Quantum Theory, The Measurement Problem, The Modal Interpretation, Non_ideal measurements. Non_Ideal Measurements Some time ago, we raised a number of rather serious objections to certain so_called "modal" interpretations of quantum theory (Albert and Loewer, 1990, 1991).1 Andrew Elby (1993) recently developed one of these objections (and added some of his own), and Richard Healey (1993) and Jeffrey Bub (1993) have recently published responses to us and Elby. It is the purpose of this note to explain why we think that their responses miss the point of our original objection. Since Elby's, Bub's, and Healey's papers contain excellent descriptions both of modal theories and of our objection to them, only the briefest review of these matters will be necessary here. -

1 Does Consciousness Really Collapse the Wave Function?

Does consciousness really collapse the wave function?: A possible objective biophysical resolution of the measurement problem Fred H. Thaheld* 99 Cable Circle #20 Folsom, Calif. 95630 USA Abstract An analysis has been performed of the theories and postulates advanced by von Neumann, London and Bauer, and Wigner, concerning the role that consciousness might play in the collapse of the wave function, which has become known as the measurement problem. This reveals that an error may have been made by them in the area of biology and its interface with quantum mechanics when they called for the reduction of any superposition states in the brain through the mind or consciousness. Many years later Wigner changed his mind to reflect a simpler and more realistic objective position, expanded upon by Shimony, which appears to offer a way to resolve this issue. The argument is therefore made that the wave function of any superposed photon state or states is always objectively changed within the complex architecture of the eye in a continuous linear process initially for most of the superposed photons, followed by a discontinuous nonlinear collapse process later for any remaining superposed photons, thereby guaranteeing that only final, measured information is presented to the brain, mind or consciousness. An experiment to be conducted in the near future may enable us to simultaneously resolve the measurement problem and also determine if the linear nature of quantum mechanics is violated by the perceptual process. Keywords: Consciousness; Euglena; Linear; Measurement problem; Nonlinear; Objective; Retina; Rhodopsin molecule; Subjective; Wave function collapse. * e-mail address: [email protected] 1 1. -

Collapse Theories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilSci Archive Collapse Theories Peter J. Lewis The collapse postulate in quantum mechanics is problematic. In standard presentations of the theory, the state of a system prior to a measurement is a sum of terms, with one term representing each possible outcome of the measurement. According to the collapse postulate, a measurement precipitates a discontinuous jump to one of these terms; the others disappear. The reason this is problematic is that there are good reasons to think that measurement per se cannot initiate a new kind of physical process. This is the measurement problem, discussed in section 1 below. The problem here lies not with collapse, but with the appeal to measurement. That is, a theory that could underwrite the collapse process just described without ineliminable reference to measurement would constitute a solution to the measurement problem. This is the strategy pursued by dynamical (or spontaneous) collapse theories, which differ from standard presentations in that they replace the measurement-based collapse postulate with a dynamical mechanism formulated in terms of universal physical laws. Various dynamical collapse theories of quantum mechanics have been proposed; they are discussed in section 2. But dynamical collapse theories face a number of challenges. First, they make different empirical predictions from standard quantum mechanics, and hence are potentially empirically refutable. Of course, testability is a virtue, but since we have no empirical reason to think that systems ever undergo collapse, dynamical collapse theories are inherently empirically risky. Second, there are difficulties reconciling the dynamical collapse mechanism with special relativity. -

Stochastic Quantum Potential Noise and Quantum Measurement

Chapter 7 Stochastic Quantum Potential Noise and Quantum Measurement Wei Wen Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.74253 Abstract Quantum measurement is the greatest problem in quantum theory. In fact, different views for the quantum measurement cause different schools of thought in quantum theory. The quandaries of quantum measurement are mainly concentrated in “stochastic measurement space”, “instantaneous measurement process” and “basis-preferred measurement space.” These quandaries are incompatible with classical physical laws and discussed many years but still unsolved. In this chapter, we introduce a new theory that provided a new scope to interpret the quantum measurement. This theory tells us the quandaries of quantum mea- surement are due to the nonlocal correlation and stochastic quantum potential noise. The quantum collapse had been completed by the noised world before we looked, and the moon is here independent of our observations. Keywords: quantum measurement, quantum collapse, quantum potential noise, Feynman path integral 1. Introduction Schrödinger cat was born from the thought experiment of Schrödinger in 1935. However, after more than 80 years, we still do not know whether it is dead or alive in its sealed box. According to the modern quantum mechanics, based on Copenhagen interpretation, the fate of this cat is entangled with the Geiger counter monitor in its box, and the cat is in a “mixed state”—both dead and alive—if we do not open the box to look at it. It is a miserable and mystical cat, which seems its fate depends on our look. -

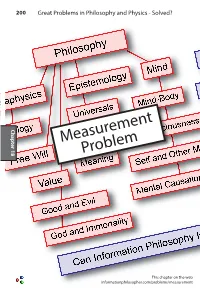

Measurement Problem

200 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 18 Chapter Measurement Problem This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/measurement Measurement 201 The Measurement Problem The “problem of measurement” in quantum mechanics has been defined in various ways, originally by scientists, and more recently by philosophers of science who question the “founda- tions” of quantum mechanics. Measurements are described with diverse concepts in quantum physics such as: • wave functions (probability amplitudes) evolving unitarily and deterministically (preserving information) according to the linear Schrödinger equation, • superposition of states, i.e., linear combinations of wave func- tions with complex coefficients that carry phase information and produce interference effects (the principle of superposition), • quantum jumps between states accompanied by the “collapse of the wave function” that can destroy or create information (Paul Dirac’s projection postulate, John von Neumann’s Process 1), • probabilities of collapses and jumps given by the square of the absolute value of the wave function for a given state, 18 Chapter • values for possible measurements given by the eigenvalues associated with the eigenstates of the combined measuring appa- ratus and measured system (the axiom of measurement), • the indeterminacy or uncertainty principle. The original measurement problem, said to be a consequence of Niels Bohr’s “Copenhagen Interpretation” of quantum mechan- ics, was to explain how our measuring instruments, which are usually macroscopic objects and treatable with classical physics, can give us information about the microscopic world of atoms and subatomic particles like electrons and photons. Bohr’s idea of “complementarity” insisted that a specific experi- ment could reveal only partial information - for example, a parti- cle’s position or its momentum. -

Empty Waves, Wavefunction Collapse and Protective Measurement in Quantum Theory

The roads not taken: empty waves, wavefunction collapse and protective measurement in quantum theory Peter Holland Green Templeton College University of Oxford Oxford OX2 6HG England Email: [email protected] Two roads diverged in a wood, and I– I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. Robert Frost (1916) 1 The explanatory role of empty waves in quantum theory In this contribution we shall be concerned with two classes of interpretations of quantum mechanics: the epistemological (the historically dominant view) and the ontological. The first views the wavefunction as just a repository of (statistical) information on a physical system. The other treats the wavefunction primarily as an element of physical reality, whilst generally retaining the statistical interpretation as a secondary property. There is as yet only theoretical justification for the programme of modelling quantum matter in terms of an objective spacetime process; that some way of imagining how the quantum world works between measurements is surely better than none. Indeed, a benefit of such an approach can be that ‘measurements’ lose their talismanic aspect and become just typical processes described by the theory. In the quest to model quantum systems one notes that, whilst the formalism makes reference to ‘particle’ properties such as mass, the linearly evolving wavefunction ψ (x) does not generally exhibit any feature that could be put into correspondence with a localized particle structure. To turn quantum mechanics into a theory of matter and motion, with real atoms and molecules comprising particles structured by potentials and forces, it is necessary to bring in independent physical elements not represented in the basic formalism. -

Observables and Measurements in Quantum Mechanics

Chapter 13 Observables and Measurements in Quantum Mechanics ill now, almost all attention has been focussed on discussing the state of a quantum system. T As we have seen, this is most succinctly done by treating the package of information that defines a state as if it were a vector in an abstract Hilbert space. Doing so provides the mathemat- ical machinery that is needed to capture the physically observed properties of quantum systems. A method by which the state space of a physical system can be set up was described in Section 8.4.2 wherein an essential step was to associate a set of basis states of the system with the ex- haustive collection of results obtained when measuring some physical property, or observable, of the system. This linking of particular states with particular measured results provides a way that the observable properties of a quantum system can be described in quantum mechanics, that is in terms of Hermitean operators. It is the way in which this is done that is the main subject of this Chapter. 13.1 Measurements in Quantum Mechanics One of the most difficult and controversial problems in quantum mechanics is the so-called measurement Quantum System problem. Opinions on the significance of this prob- S lem vary widely. At one extreme the attitude is that there is in fact no problem at all, while at the other extreme the view is that the measurement problem Measuring is one of the great unsolved puzzles of quantum me- Apparatus chanics. The issue is that quantum mechanics only M ff provides probabilities for the di erent possible out- Surrounding Environment comes in an experiment – it provides no mechanism E by which the actual, finally observed result, comes Figure 13.1: System interacting with about. -

Machine Learning Framework for Control Inclassical and Quantum

ESANN 2020 proceedings, European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, Computational Intelligence and Machine Learning. Online event, 2-4 October 2020, i6doc.com publ., ISBN 978-2-87587-074-2. Available from http://www.i6doc.com/en/. Machine learning framework for control in classical and quantum domains Archismita Dalal, Eduardo J. P´aez,Seyed Shakib Vedaie and Barry C. Sanders Institute for Quantum Science and Technology, University of Calgary, Alberta T2N 1N4, Canada Abstract. Our aim is to construct a framework that relates learning and control for both classical and quantum domains. We claim to enhance the control toolkit and help un-confuse the interdisciplinary field of machine learning for control. Our framework highlights new research directions in areas connecting learning and control. The novelty of our work lies in unifying quantum and classical control and learning theories, aided by pictorial representations of current knowledge of these disparate areas. As an application of our proposed framework, we cast the quantum-control problem of adaptive phase estimation as a learning problem. 1 Introduction The fields of classical control (C C) [1] and quantum control (QC) [2] have been treated separately and have evolved independently. Some techniques from C C theory have been successfully employed in QC, but lack of a formalised structure impedes progress of these techniques. Classical machine learning (ML) [3] and its emergent quantum counterpart [4] are prolific research fields with connections to the control field. Although these four research areas are well studied individ- ually, we require a unified framework to un-confuse the community and enable researchers to see new tools. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Applications of Near-Term Quantum Computers Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2fg3x6h7 Author Huggins, William James Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Applications of Near-Term Quantum Computers by William Huggins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor K. Birgitta Whaley, Chair Professor Martin Head-Gordon Professor Joel Moore Summer 2020 Applications of Near-Term Quantum Computers Copyright 2020 by William Huggins 1 Abstract Applications of Near-Term Quantum Computers by William Huggins Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry University of California, Berkeley Professor K. Birgitta Whaley, Chair Quantum computers exist today that are capable of performing calculations that challenge the largest classical supercomputers. Now the great challenge is to make use of these devices, or their successors, to perform calculations of independent interest. This thesis focuses on a family of algorithms that aim to accomplish this goal, known as variational quantum algorithms, and the challenges that they face. We frame these challenges in terms of two kinds of resources, the number of operations that we can afford to perform in a single quantum circuit, and the overall number of circuit repetitions required. Before turning to our specific contributions, we provide a review of the electronic structure problem, which serves as a central example for our work. We also provide a self-contained introduction to the field of quantum computing and the notion of a variational quantum algorithm. -

Chapter 11 Observables and Measurements in Quantum Mechanics 159 Story

Chapter 11 Observables and Measurements in Quantum Mechanics Till now, almost all attention has been focussed on discussing the state of a quantum sys- tem. As we have seen, this is most succinctly done by treating the package of information that defines a state as if it were a vector in an abstract Hilbert space. Doing so provides the mathematical machinery that is needed to capture the physically observed properties of quantum systems. A method by which the state space of a physical system can be set up was described in Section 8.4 wherein an essential step was to associate a set of basis states of the system with the exhaustive collection of results obtained when mea- suring some physical property, or observable, of the system. This linking of particular states with particular measured results provides a way that the observable properties of a quantum system can be described in quantum mechanics, that is in terms of Hermitean operators. It is the way in which this is done that is the main subject of this Chapter. 11.1 Measurements in Quantum Mechanics One of the most difficult and controversial problems in quantum mechanics is the so- called measurement problem. Opinions on the significance of this problem vary widely. At one extreme the attitude is that there is in fact no problem at all, while at the other extreme the view is that the measurement problem is one of the great unsolved puzzles of quantum mechanics. The issue is that quantum mechanics only provides probabili- ties for the different possible outcomes in an experiment – it provides no mechanism by which the actual, finally observed result, comes about.