Non-Tropical Northern Hemisphere Owls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCIENCE 93 Least Were Found Partly Buried in Loose Soil

JANUAkRY 24, 1919] SCIENCE 93 least were found partly buried in loose soil. the birds of the Americas, is included in the One, weighing 61 pounds, was found about six introductory mnatter. The present part com- inches in sandy soil where it had fallen and prises 1,265 species and subspecies, represent- broken into several pieces as it struck. Som-le ing 232 genera of the following families: pieces show secondary fusion surfaces, and Bubonidce, Tytonidoe, Psittacida, Steator- some appear to show tertiary fusion surfaces. nit-hidae, Alcedinidae, TodidT., Molnotide, The stone is brittle and most of the pieces are Nyctibiidoe, Caprimulgide, " Cypselidae " (lege broken; however, one fine boloid of twenty Micropodide) and Trochilidie. pounds has beeni founid and several of about Of the higher groups niothing but the names ten pounds weight. is given, but for each genus there are added The writer is preparing a detailed descrip- the authority, the original reference, and a tion of the mieteorite and the phenomena of its citation of the type. 'For each species and fall and would appreciate any data that may subspecies there appear the full technical com- have been gathered by other observers or bination; the common rname; reference to the collectors. original description; the type locality; such TERENCE T. QUIRaE essential synonymy at references (usually DEPARTMENT or GEOLOGY AND MINERAXLOGY, not over half a dozen) to Mr. Ridgway's UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, " Birds of North and AIiddle America," " The MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. Catalogue of Birds of the tritish MAuseum," original descriptionis, revisions of groups, and on March 27, 2016 SCIENTIFIC BOOKS other important papers; a brief statement of geoglaphic range; and a list of specimens Catalogue of Birds of the Americas. -

Parallel Variation in North and Middle American Screech-Owls

MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN FOUNDATION OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY JULY 1967 PARALLEL VARIATION IN NORTH AND MIDDLE AMERICAN SCREECH-OWLS BY JOE T. MARSHALL, J MONOGRAPHS OF THE WESTERN FOUNDATION OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY NO. 1 JULY 1967 PARALLEL VARIATION IN NORTH AND MIDDLE AMERICAN SCREECH-OWLS BY JOE T. MARSHALL, WESTERN FOUNDi,710' 1 OF VERTEBRATE ZOO! OGY 1100 GLENDON AVENUE • GRANITE 7-2001 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90024 BOARD OF TRUSTEES ED N. HARRISON ...... PRESIDENT FRANCES F. ROBERTS . EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT C. V. DUFF . VICE PRESIDENT J. C. VON BLOEKER, JR .. VICE PRESIDENT SIDNEY B. PEYTON SECRETARY BETTY T. HARRISON TREASURER MAURICE A. MACHRIS ....... ... .. TRUSTEE J. R. PEMBERTON ......... PRESIDENT EMERITUS WILLIAM J. SHEFFLER ..... VICE PRESIDENT EMERITUS JEAN T. DELACOUR ........ ... DIRECTOR EDITOR JACK C. VON BLOEKER, JR. A NON-PROFIT CORPORATION DEDICATED TO. THE STUDY OF ORNITHOLGY, OOLOGY, AND MAMMALOGY Date of Publication: 10 August 1967 Joe T. Marshall, Jr. Male Otus asio aikeni in its natural setting of velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina). The compressed plumage and fierce expression are due to belligerence aroused from hearing his own song played on a tape recorder in his own territory. Photographed in the field in Arizona. PARALLEL VARIATION IN NORTH AND MIDDLE AMERICAN SCREECH-OWLS JOE T. MARSHALL, JR. My objective in this paper is to provide for the first time a delineation of species of North and Middle American Otus based on acquaintance with their biological traits in the field. Next I wish to show their racial convergence in concealing color patterns. Finally, I attempt to portray the dramatic geographic variation in those evanescent colors and patterns of fresh autumn plumage, in recently collected specimens (largely taken by myself). -

Tc & Forward & Owls-I-IX

USDA Forest Service 1997 General Technical Report NC-190 Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere Second International Symposium February 5-9, 1997 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Editors: James R. Duncan, Zoologist, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Department of Natural Resources Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB CANADA R3J 3W3 <[email protected]> David H. Johnson, Wildlife Ecologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA, USA 98501-1091 <[email protected]> Thomas H. Nicholls, retired formerly Project Leader and Research Plant Pathologist and Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN, USA 55108-6148 <[email protected]> I 2nd Owl Symposium SPONSORS: (Listing of all symposium and publication sponsors, e.g., those donating $$) 1987 International Owl Symposium Fund; Jack Israel Schrieber Memorial Trust c/o Zoological Society of Manitoba; Lady Grayl Fund; Manitoba Hydro; Manitoba Natural Resources; Manitoba Naturalists Society; Manitoba Critical Wildlife Habitat Program; Metro Propane Ltd.; Pine Falls Paper Company; Raptor Research Foundation; Raptor Education Group, Inc.; Raptor Research Center of Boise State University, Boise, Idaho; Repap Manitoba; Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada; USDI Bureau of Land Management; USDI Fish and Wildlife Service; USDA Forest Service, including the North Central Forest Experiment Station; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; The Wildlife Society - Washington Chapter; Wildlife Habitat Canada; Robert Bateman; Lawrence Blus; Nancy Claflin; Richard Clark; James Duncan; Bob Gehlert; Marge Gibson; Mary Houston; Stuart Houston; Edgar Jones; Katherine McKeever; Robert Nero; Glenn Proudfoot; Catherine Rich; Spencer Sealy; Mark Sobchuk; Tom Sproat; Peter Stacey; and Catherine Thexton. -

Unusual Results from Pellet Analysis of the American Barn Owl, Tyto Alba Pratincola (Bonaparte) Kenneth N

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 33 Article 38 1979 Unusual Results from Pellet Analysis of the American Barn Owl, Tyto alba pratincola (Bonaparte) Kenneth N. Paige Arkansas State University Chris T. McAllister Arkansas State University C. Renn Tumlison Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Paige, Kenneth N.; McAllister, Chris T.; and Tumlison, C. Renn (1979) "Unusual Results from Pellet Analysis of the American Barn Owl, Tyto alba pratincola (Bonaparte)," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 33 , Article 38. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol33/iss1/38 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This General Note is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 33 [1979], Art. 38 Arkansas Academy of Science Table 2. Teacher evaluations of college courses. had course 5 B3 General Bio] >f-y 1.53 17 91 General Boti iy 1.214 15 63 General Zool >gy i.00 6 33 Cell Bl 1 .'V 1.33 11 78 Genetic 1.29 9 50 General Boo] '*y 1.51 13 72 General Phyi ol igy 1.15 13 72 Human Ana tony 1 ,07 11 61 Human Physiology 1.18 1 5 Human Sexuality i. -

Eastern Screech-Owl (Otus Asio)

Wild Things in Your Woodlands Eastern Screech-Owl (Otus asio) The Eastern Screech-Owl is a small, nocturnal, predatory bird, about 8.5 inches in size. The robin-sized owl has short, rounded wings, bright yellow eyes, and a rounded head with visible “ear tufts.” The ear tufts, which the bird raises when alarmed, are otherwise inconspicuous. The facial disc is lightly mottled and has a prominent dark rim along the sides. The tail and the flight feathers of the wings are barred. The eastern screech-owl occurs in two color morphs, red and gray. The red color morph is more common near the coast, and the grey color morph is more common in the interior of the state. Male and female screech owls look alike. In the fall, light and temperature conditions mimic those of spring, and birds and amphibians sometimes begin calling again, a behavior called autumnal recrudescence. At this time, the screech owl’s tremulous call can be heard in a variety of habitats including open woodlands, deciduous forests, parks, farms, riparian areas, swamps, old orchards, small woodlots, and suburban areas. This small owl is an often common, nocturnal bird in much of New York State, though it is uncommon in heavily forested regions, at high elevations, and on Long Island. The screech owl is a year-round resident, spending both the breeding and non-breeding seasons in the same area. The screech owl nests in natural hollows or cavities in trees, old woodpecker holes, nesting boxes, and occasionally crevices in the sides of buildings. Screech owl pairs may roost together in the same tree cavity during the day throughout the breeding season. -

Montana Owl Workshop April 19-24, 2019 © 2018

MONTANA OWL WORKSHOP APRIL 19-24, 2019 © 2018 High, wide, and handsome, Montana is the country’s fourth largest state, encompassing 145,392 square miles (376,564 square kilometers), and has one of the lowest human densities of all states; about six to seven people per square mile. Its biological diversity and variable climate reflects its immensity. Among its alpine tundra, coniferous forests, plains, intermountain valleys, mountains, marshes, and river breaks, Montana lists 433 species of birds, 109 species of mammals, 13 species of amphibians, and 18 species of reptiles. Montana also maintains about 2,080 species of native plants. Join researchers for four full days of learning how to survey, locate, and observe owls in the field. Montana boasts the largest number of breeding owl species in any state within the United States. Fifteen species of owls occur in Montana, of which 14 species breed: American Barn Owl, Flammulated Owl, Eastern Screech Owl, Western Screech Owl, Great Horned Owl, Barred Owl, Great Gray Owl, Northern Hawk Owl, Northern Pygmy Owl, Burrowing Owl, Boreal Owl, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Long-eared Owl, and Short-eared Owl. Snowy Owls are winter visitors only. Although all species will not be seen, chances are good for five to seven species, and with some luck, eight species are possible. Highlights can include Great Gray Owl, Northern Pygmy Owl, Boreal Owl, and Northern Saw-whet Owl. It’s not often the public has an opportunity to follow wildlife researchers on projects. During this educational workshop, we will meet and observe field researchers of the Owl Research Institute (ORI) who have been conducting long-term studies on several species of owls. -

Comparison of Food Habits of the Northern Saw-Whet Owl (Aegolius Acadicus) and the Western Screech-Owl (Otus Kennicottii) in Southwestern Idaho

Comparison of Food Habits of the Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) and the Western Screech-owl (Otus kennicottii) in Southwestern Idaho Charlotte (Charley) Rains1 Abstract.—I compared the breeding-season diets of Northern Saw- whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) and Western Screech-owls (Otus kennicottii). Prey items were obtained from regurgitated pellets collected from saw-whet owl and screech-owl nests found in nest boxes in the Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area in southwestern Idaho. A total of 2,250 prey items of saw-whet owls and 702 prey items of screech-owls were identified. Saw-whet owl diet was analyzed for the years 1990-1993; screech-owl diet was analyzed for 1992 only. The most frequently found prey items in the saw-whet owls diet were: Peromyscus, Mus, Microtus and Reithrodontomys; there were no significant differences among years. When saw-whet owl prey frequency data were pooled across years and compared to the 1992 screech-owl data, significant differences in diet were found. However, a comparison of the 1992 saw-whet prey frequency data with the screech-owl data showed no significant differences. In addition, the among year saw-whet owl prey biomass was analyzed, and again there were no significant differences. Micro- tus, followed by Mus, accounted for the largest proportion of prey biomass (by percent) in the diets of saw-whet owls for all years. When saw-whet owl prey biomass data were pooled across years and compared to the 1992 screech-owl prey biomass, significant differ- ences in diet were found. The 1992 saw-whet prey biomass com- pared to the 1992 screech-owl prey biomass also was significantly different. -

OWLS of OHIO C D G U I D E B O O K DIVISION of WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O

OWLS OF OHIO c d g u i d e b o o k DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O Owls have longowls evoked curiosity in In the winter of of 2002, a snowy ohio owl and stygian owl are known from one people, due to their secretive and often frequented an area near Wilmington and two Texas records, respectively. nocturnal habits, fierce predatory in Clinton County, and became quite Another, the Oriental scops-owl, is behavior, and interesting appearance. a celebrity. She was visited by scores of known from two Alaska records). On Many people might be surprised by people – many whom had never seen a global scale, there are 27 genera of how common owls are; it just takes a one of these Arctic visitors – and was owls in two families, comprising a total bit of knowledge and searching to find featured in many newspapers and TV of 215 species. them. The effort is worthwhile, as news shows. A massive invasion of In Ohio and abroad, there is great owls are among our most fascinating northern owls – boreal, great gray, and variation among owls. The largest birds, both to watch and to hear. Owls Northern hawk owl – into Minnesota species in the world is the great gray are also among our most charismatic during the winter of 2004-05 became owl of North America. It is nearly three birds, and reading about species with a major source of ecotourism for the feet long with a wingspan of almost 4 names like fearful owl, barking owl, North Star State. -

Barn Owls in the Vineyards

VITICULTURE Barn Owls in the Vineyards Natural Born Killers Story and photos by Christopher Sawyer re you sick of pocket gophers and swoop and strike quickly before the prey can other rodents gnawing away on your react. vines and other costly investments on your property? Well, the answer to this PUTTING BARN OWLS TO WORK Adilemma could be as easy as purchasing a small These impressive attributes caught the atten- box and befriending a feathery creature tion of Mark Browning, a professional 2 with golden wings and a heart animal trainer and field researcher shaped face. for the Pittsburgh Zoo. Brown- Welcome to the kingdom ing’s knowledge of barn owls of the barn owl, the most inspired him to develop a widespread land bird in way to put the predatory the world. bird to work in rodent- Known for its vora- plagued vineyards and cious appetite, mag- farms: the Barn Owl nificent plumage and Box (see sidebar). Con- amazing flying skills, the barn owl is a mem- ber of the Tytonidae family. Highly success- ful in natural breeding Barn owl boxes can and longevity, the mul- help growers reduce tiple subspecies of this populations of gophers Vineyard & Winery Management • May/Jun 2009 www.vwm-online.com bird have spread around the and other rodents in globe. Currently, the two best- vineyards. (Photo by Mark known races are the barn owl of Browning.) Europe, Tyto alba alba, and the North American barn owl, Tyto alba pratincola. At a Glance In terms of living conditions, the barn owl is a hole nester that lives in closed quarters or Rodents like pocket gophers can wreak dark cavities found inside hollow trees, barns, havoc in vineyards, and are difficult to sheds and other outbuildings. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

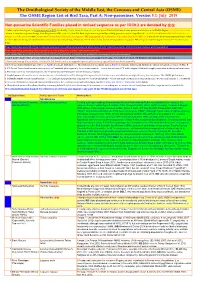

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Djibouti & Somaliland Rep 10

DJIBOUTI & SOMALILAND 4 – 25 SEPTEMBER 2010 TOUR REPORT LEADER: NIK BORROW assisted by ABDI JAMA Warlords, pirates, chaos and lawlessness are all associated with Somalia. What isn’t always appreciated is that what was once British Somaliland has, since 1991, been the Republic of Somaliland, and this peaceful enclave doesn’t take kindly to being associated with the eastern half of the country’s descent into anarchy. The tiny country of Djibouti is also quite stable forming as it does an important port to the Horn of Africa at the narrowest part of the Red Sea and at the mouth of the Rift Valley. Our adventurous group set off on this pioneering tour to these countries in order to look for some of the endemics and specialties of the region that had until recently been considered unattainable. Little ornithological work has been carried out in the country since the late 1980’s but there had already been a small number of intrepid birders set foot within the country’s borders this year. However, our tour was aiming to be the most thorough and exhaustive yet and we succeeded remarkably well in finding some long lost species and making some significant ornithological discoveries. We amassed a total of 324 species of birds of which all but two were seen and 23 species of mammals. The mouth-watering endemics and near-endemics that were tracked down and all seen well were Archer’s Buzzard, Djibouti Francolin, Little Brown Bustard, Somali Pigeon, Somali Lark, Lesser Hoopoe-lark, Somali Wheatear, Somali Thrush, Somali Starling, Somali Golden-winged Grosbeak and Warsangli Linnet. -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt.