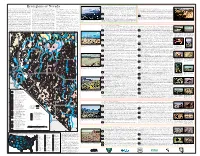

Obsidian Studies in the Truckee Meadows, Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

HISTORY of the TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST a Compilation

HISTORY OF THE TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST A Compilation Posting the Toiyabe National Forest Boundary, 1924 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bridgeport and Carson Ranger District Centennial .................................................................... 126 Forest Histories ........................................................................................................................... 127 Toiyabe National Reserve: March 1, 1907 to Present ............................................................ 127 Toquima National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ....................................................... 128 Monitor National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ........................................................ 128 Vegas National Forest: December 12, 1907 – July 2, 1908 .................................................... 128 Mount Charleston Forest Reserve: November 5, 1906 – July 2, 1908 ................................... 128 Moapa National Forest: July 2, 1908 – 1915 .......................................................................... 128 Nevada National Forest: February 10, 1909 – August 9, 1957 .............................................. 128 Ruby Mountain Forest Reserve: March 3, 1908 – June 19, 1916 .......................................... -

Watershed Ed

Spring 2019 WATERSHED ED Promoting watershed education and stewardship in Nevada STEM Education in Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak’s top priority is education, and the State’s STEM Advisory Council’s vision is that “every student in Nevada will have access and opportunities to experience a high-quality science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education, with the ultimate objective that students are prepared to thrive in the New Nevada economy…” All schools are encouraged to adopt practices that engage and expose students to real-world problem solving, creative design, innovation, critical thinking, and career opportunities through STEM-focused formal and informal education. Schools in Nevada that meet the highest standards of STEM instruction are identified and recognized as STEM schools, as outlined in the Governor’s Designated STEM School Action Guide. Look Inside The Governor and his wife recently visited and 1 Stem Education in Nevada participated in Bordewich Bray Elementary School’s Family Science Night presented by Sierra Nevada 2 2019 Golden Pinecone Awards Journeys in Carson City. He spoke about how important education is to Nevada and how he was 3 Featured Watershed committed to supporting teachers, educators, students and families around the State. 4 NDOW Aquatic Fauna—Beaver It’s not just the schools that must recognize and 6 Science Career Highlight participate in the STEM experience. Families, businesses, industry and the community at large are 8 Opportunities/Events also encouraged to help drive STEM curriculum and experiences. 9 Resources/Contact (Continued on page 5) FEATURED Science Career Learn what it’s like to be a water quality scientist (see page 6). -

Committee for the Review and Oversight of the TRPA and the Marlette Lake Water System

STATE OF NEVADA Department of Conservation & Natural Resources Steve Sisolak, Governor Bradley Crowell, Director Charles Donohue, Administrator MEMORANDUM DATE: December 11, 2019 TO: Committee for the Review and Oversight of the TRPA and the Marlette Lake Water System THROUGH: Charles Donohue, Administrator FROM: Meredith Gosejohan, Tahoe Program Manger SUBJECT: California spotted owls in Nevada The following information on the California spotted owl in Nevada is in response to questions from the Committee during the meeting held on November 19, 2019. Currently, there is only one known nesting pair of spotted owls in the State of Nevada. The pair were discovered in Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park in 2015 and have occupied the same territory every year since. The territory is monitored annually by the Nevada Tahoe Resource Team’s (NTRT) biologist from the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). The pair has successfully fledged one juvenile from the nest in three different years: 2015, 2017, and 2018. There have also been five documented incidental spotted owl sightings in other parts of the Carson Range since 2015. These spotted owls are a subspecies called the California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis occidentalis). There are two other subspecies in the western United States (Northern and Mexican), both of which are federally listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The California spotted owl was recently petitioned for federal listing as well, but the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced in November 2019, that listing was not warranted at this time. (Click here to read the decisions summary) Spotted owls are native to the Tahoe Basin, though they have been relatively rare on the Nevada side and are typically observed on the California side or other parts of the Sierra Nevada. -

Field Trip Summary Report for Sierra Nevadas, California: Chico NE, SE

\ FIElD TRIP SUMMARY FOR SIERRA NEVADAS, CALIFORNIA CHICO NE, SE AND SACRAMENTO NE I. INTRODUCTION Field reconnaissance of the work area is an integral part for the accurate interpretation of aerial photography. Photographic signatures are compared to the actual wetland's appearance in the field by observing vegetation, soil and topo~raphy. This information is weighted with seasonality and conditIOns at both dates of photography and ground truthing. The project study area was located in northern California's Sierra Nevada Mountains. Ground truthing covered the area of each 1:100,000: Chico NE, Chico SE, and Sacramento NE. This field summary describes the data we were able to collect on the various wetland sites and the plant communities observed. II. FIELD MEMBERS Barbara Schuster Martel Laboratories, Inc. Dennis Peters U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service III. FIELD DATES July 27 - August 2, 1988 IV. AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY Type: Color Infrared Transparencies Scale: 1:58,000 V. COLLATERAL DATA U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangles Soil Survey of HI Dorado Area. California, 1974. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey of Nevada County Area. California, 1975. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. 1 Soil Survey of Sierra Valley Area. California. Parts of Sierra. Plumas. and Lassen Counties, 1975. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey - Tahoe Basin Area. California and Nevada, 1974. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey - Amador Area. California, 1965. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. -

Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan O the Sky Highway T

Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Highway to the Sky CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE & VISION PURPOSE & VISION 1 PLAN PURPOSE 2 CORRIDOR SETTING 3 VISION & GOALS 6 STAKEHOLDER & PUBLIC OUTREACH 7 CHAPTER 2: MOUNT ROSE SCENIC BYWAY’S INTRINSIC VALUES INTRINSIC VALUES 19 TERRAIN 20 OWNERSHIP 22 LAND USE & COMMUNITY RESOURCES 24 VISUAL QUALITY 26 CULTURAL RESOURCES 30 RECREATIONAL RESOURCES 34 HYDROLOGY 40 VEGETATION COMMUNITIES & WILDLIFE 42 FUEL MANAGEMENT & FIRES 44 CHAPTER 3: THE HIGHWAY AS A TRANSPORTATION FACILITY TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES 47 EXISTING ROADWAY CONFIGURATION 48 EXISTING TRAFFIC VOLUMES & TRENDS 49 EXISTING TRANSIT SERVICES 50 EXISTING BICYCLE & PEDESTRIAN FACILITIES 50 EXISTING TRAFFIC SAFETY 50 EXISTING PARKING AREAS 55 PLANNED ROADWAY IMPROVEMENTS 55 CHAPTER 4: ENHANCING THE BYWAY FOR VISITING, LIVING & DRIVING CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES & ACTION ITEMS 57 PRESERVE THE SCENIC QUALITY & NATURAL RESOURCES 59 BALANCE RECREATION ACCESS WITH TRANSPORTATION 68 & SAFETY NEEDS CONNECT PEOPLE WITH THE CORRIDOR 86 PROMOTE TOURISM 94 CHAPTER 5: CORRIDOR STEWARDSHIP CORRIDOR STEWARDSHIP 99 MANAGING PARTNERS 100 CURRENT RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTS 102 | i This Plan was funded by an On Our Way grant from the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency and a Federal Scenic Byway Grant from the Nevada Department of Transportation. ii | Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan CHAPTER ONE 1 PURPOSE & VISION Chapter One | 1 The Corridor PLAN PURPOSE The Mount Rose Scenic Byway is officially named the “Highway to the Management Sky” and offers travelers an exciting ascent over the Sierra Nevada from Plan identifies the sage-covered slopes of the eastern Sierra west to Lake Tahoe. Not only goals, objectives does the highway connect travelers to a variety of recreation destinations and cultural and natural resources along the Byway, it also serves as a and potential minor arterial connecting both tourists and commuters from Reno to Lake enhancements to Tahoe. -

Truckee River 2007

NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE STATEWIDE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT FEDERAL AID JOB PROGRESS REPORT F-20-54 2018 TRUCKEE RIVER WESTERN REGION NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE, FISHERIES DIVISION ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT Table of Contents SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................. 1 OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 3 PROCEDURES ............................................................................................................... 3 FINDINGS ................................................................................................................... 5 MANAGEMENT REVIEW ............................................................................................. 17 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................. 18 NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE, FISHERIES DIVISION ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT State: Nevada Project Title: Statewide Fisheries Program Job Title: Truckee River Period Covered: January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018 SUMMARY On April 1, 2018, the designated end of the snow-measuring season, the snowpack in the Truckee River Basin stood at 75% of the median for that date and the amount of precipitation for the year stood at 90% of average. While the 2017/18 winter was slightly -

Conservation Plan

CONSERVATION PLAN ACKNOWLEDGMENTS City Council Robert Cashell, Mayor Pierre Hascheff, At-Large Dan Gustin, Ward One Sharon Zadra, Ward Two Jessica Sferrazza, Ward Three Dwight Dortch, Ward Four David Aiazzi, Ward Five Office of the City Manager Charles McNeely, City Manager Mary Hill, Assistant City Manager Susan Schlerf, Assistant City Manager Donna Dreska, Chief of Staff Planning Commission Jim Newberg, Chair Kevin Weiske, Vice Chair Doug Coffman Lisa Foster Dennis Romeo Jason Woosley Community Development Department John B. Hester, AICP, Community Development Director John Toth, P.E., Assistant Community Development Director Claudia Hanson, AICP, Deputy Community Development Director - Planning Nathan Gilbert, Associate Planner Amended by City Council October 22, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Plan Organization ............................................................................................1 Boundary .........................................................................................................1 Time Frame .....................................................................................................1 Relationship to Other Plans .............................................................................1 Need for Conservation Plan.............................................................................1 Truckee River...................................................................................................2 Development Constraints............................................................................4 -

Section 1: Introduction

Carson Range Fuel Reduction and Wildfire Prevention Strategy Section 1: Introduction Purpose of this Plan This comprehensive fuels reduction and wildfire prevention plan is a unified, multi-jurisdictional strategic synopsis of the planning efforts of local, county, state, tribal, and federal entities. The proposed projects in this plan provide a 10-year strategy to reduce the risk of large and destructive wildfire in the Carson Range planning area. The plan’s outcome is to 1) propose projects that create “community defensible space”, 2) comprehensively display all proposed fuel reduction treatments, and 3) facilitate communication and cooperation among those responsible for plan implementation. If implemented, this plan will provide greater protection to the people, infrastructure, and resources in the planning area. This plan was developed to comply with the White Pine County Conservation, Recreation, and Development Act of 2006 (Public Law 109-432 [H.R.6111]), which amended the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act of 1998 (Public Law 105-263) to include the following language: “development and implementation of comprehensive, cost-effective, multi- jurisdictional hazardous fuels reduction and wildfire prevention plans (including sustainable biomass and biofuels energy development and production activities) for the Lake Tahoe Basin (to be developed in conjunction with the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency), the Carson Range in Douglas and Washoe Counties and Carson City in the State, and the Spring Mountains in the State, that are-- (I) subject to approval by the Secretary; and (II) not more than 10 years in duration” This comprehensive plan is supported by 15 partners who each have a role in wildland fuels or fire management in the planning area (see “Agencies Involved” below). -

Board of Fire Commissioners, Truckee Meadows Fire

BOARD OF FIRE COMMISSIONERS TRUCKEE MEADOWS FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT TUESDAY 9:00 A.M. NOVEMBER 10, 2020 PRESENT: Bob Lucey, Chair Marsha Berkbigler, Vice Chair* Kitty Jung, Commissioner (via telephone) Vaughn Hartung, Commissioner Jeanne Herman, Commissioner Janis Galassini, County Clerk Charles Moore, Fire Chief David Watts-Vial, Deputy District Attorney (via Zoom) The Board convened at 9:00 a.m. in regular session in the Commission Chambers of the Washoe County Administration Complex, 1001 East Ninth Street, Reno, Nevada. Following the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of our Country, the Clerk called the roll and the Board conducted the following business: 20-153F AGENDA ITEM 3 Public Comment. There was no response to the call for public comment. 20-154F AGENDA ITEM 4 Announcements/Reports. Truckee Meadows Fire Protection District Chief Charles Moore said green waste pile burning was slated to begin in December and would continue through January or February 2021. An announcement would soon be released regarding whether owners with large properties would be allowed to burn green waste on their land. Commissioner Hartung expressed appreciation for a letter of support for an advanced signal warning system to be installed near the intersection of Pyramid Highway and Calle de la Plata. An update was expected from the Nevada Department of Transportation regarding the possibility of installing systems along the entire Pyramid Highway corridor, as well as in the Mount Rose Highway area. Commissioner Hartung expressed a desire to work proactively on any potential safety issues. Commissioner Jung wondered whether a permit would be required for the open burning mentioned by Chief Moore and what the minimum acreage required for property owners to burn green waste on-site would need to be. -

Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan

Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan PREPARED BY SUSTAIN ENVIRONMENTAL INC FOR THE California Department of Fish and Game North Central Region December 2009 SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY INITIATIVE rptfic'iii Printed on sustainable paper products COVER: Appleton Utopia Forest Stewardship Council certified by Smartwood (a Rainforest Alliance program), ISO 14001 Registered Environmental Management System, EPA SmartWay Transport Partner Interior pages: Navigator Hybrid 85%-100% recycled post consumer waste blended with virgin fiber, Forest Stewarship Council certified chain of custody, ISO 14001 Registered Environmental Management System, 80% energy from renewable resources Divider pages (main body): Domtar Colors Sustainable Forest Initiative fiber sourcing certified, 30% post consumer waste Divider pages (appendices): Hammermill Fore MP 30% post consumer waste PDF VERSION DESIGNED FOR DUPLEX PRINTING State of California The Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan Sierra and Lassen Counties, California UPDATED: DECEMBER 2009 PREPARED FOR: California Department of Fish and Game North Central Region Headquarters 1701 Nimbus Road, Suite A Rancho Cordova, California 95670 Attention: Terri Weist 530.644.5980 PREPARED BY: Sustain Environmental Inc. 3104 "O" Street #164 Sacramento, California 95816 916.457.1856 APPRnvFn RY- Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Land Management Plan Table of Contents................................................................................................................................................i