Career Paths of Power Five Athletic Directors: a Social Network Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-12 USBWA Directory

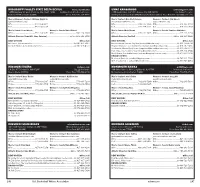

MISSISSIPPI VALLEY STATE DELTA DEVILS mvsu.edu/athletics UMKC KANGAROOS umkckangaroos.com 14000 Highway 82 West, Itta Bena, MS 38941-1400 Southwestern Athletic Conference 5100 Rockhill Rd., SRC 201, Kansas City, MO 64110 The Summit League Harrison HPER Complex (6,000) Press Row: 662-254-6641 Swinney Recreation Center(1,504)/Municipal Auditorium (9,827) Press Row: 816-235-6903/513-5217 Men’s/Women’s Contact: William Bright Jr. Men’s Contact: Rob McCutcheon Women’s Contact: Nik Busch [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Offi ce .........................................662-254-3011 Offi ce .........................................816-235-1034 Offi ce .........................................816-235-6618 Cell ............................................662-299-5534 Cell ............................................816-284-9251 Cell ............................................ 816-529-7694 Men’s Coach: Sean Woods Women’s Coach: Nate Kilbert Men’s Coach: Matt Brown Women’s Coach: Candace Whitaker Offi ce .........................................662-254-3561 Offi ce .........................................601-254-3549 Offi ce .........................................816-235-1036 Offi ce .........................................816-235-1264 Athletic Director: Donald R. Sims (Interim) .............................................Offi ce: 662-254-3550 Athletic Director: Tim Hall .........................................................................Offi ce: 816-235-1020 BEAT WRITERS Offi ce/Cell BEAT WRITERS Offi ce/Cell Bill Burris, -

2017 Opponents

2017 Opponents PortlaNnIKd ES tIantveit Taotiuornnaal ment Northwestern State Seton Hall Oklahoma Aug. 25, 3:30 p.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 9 a.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 6 p.m., Norman, Okla. Location ..............................Natchitoches, La. Location ...........................South Orange, N.J. Location ..................................Norman, Okla. Founded .................................................1884 Founded .................................................1856 Founded .................................................1890 Enrollment .............................................9,819 Enrollment .............................................9,700 Enrollment ...........................................31,250 Nickname .................................Lady Demons Nickname ............................................Pirates Nickname ..........................................Sooners Colors .........................Purple, White, Orange Colors ....................................Blue and White Colors ............................Crimson and Cream Conference ....................................Southland Conference .......................................Big East Conference ..........................................Big 12 Arena (Capacity) ....Prather Coliseum (3,900) Arena (Capacity) ..Walsh Gymnasium (2,600) Arena (Capacity) ......McCasland Field House President .............................Dr. Chris Maggio President ...................Mary Meehan (interim) (5,000) Athletics Director .........................Greg Burke Director -

June 5, 2020 Commissioner Kevin Warren Big Ten Conference 5440

June 5, 2020 Commissioner Kevin Warren Big Ten Conference 5440 Park Place Rosemont, IL 60018 Dear Commissioner Warren, We are a consortium of advocates for women and girls in sports. Access to and participation in sports improves the lives of all students, and that is particularly true for girls and women. During this time of COVID-19, we are writing to remind you of your institutional obligation to uphold Title IX.1 We understand that these are trying times for collegiate institutions, including athletics departments. In response to financial pressures, we have become aware that some universities are considering program cuts to their athletic programs.2 As the commissioner of the 1 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688. 2 Sallee, Barrett. “Group of Five Commissioners Ask NCAA to Relax Rules That Could Allow More Sports to Be Cut.” CBS Sports, April 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/group-of-five- commissioners-ask-ncaa-to-relax-rules-that-could-allow-more-sports-to-be-cut/. (Five Conferences—American Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA, Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mountain West Conference, and the Sun Belt Conference—formally requested the NCAA to lower the minimum team requirements for Division 1 membership. The NCAA subsequently denied their request.) See also: ⬧ Hawkins, Stephen. “Slashed St. Ed's: Reeling School Cuts Teams, Breaks Hearts.” ABC News. ABC News Network, May 7, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/slashed-st-eds-reeling-school- cuts-teams-breaks-70563956. (Saint Edward's University cuts six varsity teams.); ⬧ Keith, Braden. “After Cuts, Sonoma State Says It Will Add Roster Spots to Comply with Title IX.” SwimSwam, May 1, 2020. -

2019 Annual Meeting Program

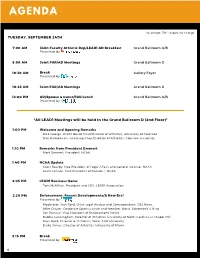

AGENDA *As of Sept. 17th - Subject to Change TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24TH 7:00 AM Joint Faculty Athletic Rep/LEAD1 AD Breakfast Grand Ballroom A/B Presented by 8:00 AM Joint FAR/AD Meetings Grand Ballroom D 10:30 AM Break Gallery Foyer Presented by 10:45 AM Joint FAR/AD Meetings Grand Ballroom D 12:00 PM AD/Spouse & Guest/FAR Lunch Grand Ballroom A/B Presented by *All LEAD1 Meetings will be held in the Grand Ballroom D (2nd Floor)* 1:00 PM Welcome and Opening Remarks Rick George, LEAD1 Board Chair/Director of Athletics, University of Colorado Dan Radakovich, Incoming Chair/Director of Athletics, Clemson University 1:10 PM Remarks from President Emmert Mark Emmert, President, NCAA 1:40 PM NCAA Update Scott Bearby, Vice President of Legal Affairs and General Counsel, NCAA Kevin Lennon, Vice President of Division I, NCAA 2:05 PM LEAD1 Business Items Tom McMillen, President and CEO, LEAD1 Association 2:20 PM Enforcement: Recent Developments/A New Era? Presented by Moderator: Jack Ford, Chief Legal Analyst and Correspondent, CBS News Mike Glazier, Corporate Sports Lawyer and Member, Bond, Schoeneck & King Jon Duncan, Vice President of Enforcement, NCAA Bubba Cunningham, Director of Athletics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Ross Bjork, Director of Athletics, Texas A&M University Blake James, Director of Athletics, University of Miami 3:15 PM Break Presented by 4 AGENDA *As of Sept. 17th - Subject to Change TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24TH FAR/AD Breakfast Panel 3:30 PM AD Accountability/Attestation - What Now? Presented by Moderator: Chris Del -

Big Ten Conference Handbook

BIG TEN CONFERENCE HANDBOOK 2017-2018 University of Illinois Indiana University University of Iowa University of Maryland University of Michigan Michigan State University University of Minnesota University of Nebraska Northwestern University Ohio State University Penn State University Purdue University Rutgers University University of Wisconsin The Big Ten Conference 5440 Park Place Rosemont, Illinois 60018 (847) 696-1010 Home Page: http://www.bigten.org The Big Ten Conference, Inc., and the Big Ten Conference logo are registered trademarks of the Conference and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Conference. TABLE OF CONTENTS DIRECTORY AND CALENDAR INFORMATION Members of the Big Ten Conference & Joint Group Governance Groups ............................................ 1 2017-18 Standing Committees and Conference Commissions .............................................................. 3 2017-18 Conference Calendar – Governing Body Meetings ................................................................. 5 Institutional Calendars for 2017-18 Academic Year ............................................................................. 7 Institutional Calendars for 2018-19 Academic Year ............................................................................. 9 Statement of Guiding Principles (PPG) ............................................................................................... 11 Delegation and Communications Guidelines ...................................................................................... -

TABLE of CONTENTS the BIG TEN CONFERENCE CONTENTS Headquarters and Conference Center Media Information

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE BIG TEN CONFERENCE CONTENTS Headquarters and Conference Center Media Information .........................................................................................................2 5440 Park Place • Rosemont, Illinois 60018 • Phone: 847-696-1010 Big Ten Conference History ........................................................................................3 New York City Office 900 Third Avenue, 36th Floor • New York, N.Y., 10022 • Phone: 212-243-3290 Commissioner James E. Delany .................................................................................4 Website: bigten.org Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten .........................................................................................5 Facebook: /BigTenConference Twitter: @B1GMBBall, @BigTen 2018-19 Composite Schedule .................................................................................. 6-9 BIG TEN STAFF – ROSEMONT Commissioner: James E. Delany 2018-19 TEAM CAPSULES ................................................................................... 10-23 Deputy Commissioner, COO: Brad Traviolia Illinois Fighting Illini ..................................................................................10 Deputy Commissioner, Public Affairs: Diane Dietz Indiana Hoosiers ......................................................................................11 Senior Associate Commissioner, Television Administration: Mark Rudner Iowa Hawkeyes........................................................................................12 Associate -

2014 Revised Landfall Tradition Media Kit.Indd

2014 Landfall Tradition October 24-26, 2014 Pete Dye Course Country Club of Landfall Wilmington, N.C. Hosted by UNCW Tournament Field UNCW Notre Dame Alabama Ohio State Arizona Oklahoma State UCF Penn State Duke Purdue Florida South Carolina Michigan State Tennessee N.C. State Virginia North Carolina Wake Forest Tournament Schedule Course Yardage Thursday, Oct. 23, 2014 Pete Dye Course/CCL 7:30 a.m. Practice Rounds College Teams 12:30 p.m. College-Am Tournament Pete Dye Course Hole Par Yardage 6:00 p.m. Reception Nicklaus Cubhouse 1 4 354 6:45 p.m. Dinner of Champions Nicklaus Clubhouse 2 3 120 Friday, Oct. 24, 2014 3 4 345 8:21 a.m. Tee Times on #1 and #10 Tees Pete Dye Course 4 5 485 5 4 361 Saturday, Oct. 25, 2014 6 5 496 8:21 a.m. Tee Times on #1 and #10 Tees Pete Dye Course 7 4 384 8 3 149 Sunday, Oct. 26, 2014 9 4 392 8:45 a.m. Tee Times (Shotgun Start) Pete Dye Course Out ` 36 3086 2:45 p.m. Awards Presentation Hole Par Yardage 10 4 360 11 4 338 12 5 490 13 3 167 14 4 383 15 4 335 16 3 158 17 4 375 18 5 467 In 36 3073 Total 72 6159 UNCW “Seahawks” Alabama “Crimson Tide” School: University of North Carolina Wilmington School: University of Alabama Founded: 1947 Founded: 1831 Enrollment: 14,500 Enrollment: 36,155 Colors: Teal, Navy and Gold Colors: Crimson and White Conference: Colonial Athletic Association Conference: Southeastern Conference Chancellor: Dr. -

2017-18 Pac-12 Women's Basketball Prospectus

NOTES 2017-18 PAC-12 BASKETBALL // PROSPECTUS 2017-18 PAC-12 WOMEN'S BASKETBALL QUICK REFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS Quick Reference ........................................1 ARIZONA UCLA 106 McKale Center • Tucson, AZ 85721-0096 Morgan Center • 325 Westwood Plaza TEAM INFORMATION .......................2-13 Office: (520) 621-4163 / Fax: (520) 621-2681 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1639 Arizona Wildcats ........................................2 http://www.arizonawildcats.com Office: (310) 206-6831 / Fax: (310) 825-8664 Arizona State Sun Devils .............................3 Head Coach: http://www.uclabruins.com Adia Barns (Arizona 1998) ......................Second Year Head Coach: California Golden Bears ..............................4 Record at Arizona/Years .................................14-16/1 Cori Close (UC Santa Barbara 1993) ...... Seventh Year Colorado Buffaloes .....................................5 Career Record/Years ......................................14-16/1 Record at UCLA/Years ..................................123-78/6 Oregon Ducks ............................................6 Women’s Basketball SID: Career Record/Years ....................................123-78/6 Oregon State Beavers .................................7 Adam Gonzales, Asst. Dir. .......................................... Women’s Basketball SID: ............................. [email protected] Ryan Finney, Assoc. Dir. [email protected] Stanford Cardinal .......................................8 UCLA Bruins ..............................................9 -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

BIG TEN CONFERENCE Anti-Hate and Anti-Racism Coalition

BIG TEN CONFERENCE Anti-Hate and Anti-Racism Coalition PAGE 1 PAGE 1 BIG TEN CONFERENCE Anti-Hate and Anti-Racism Coalition UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS RA’VON BONNER KENNEDY COLLINS DR. STEPHON FUQUA Student-Athlete Student-Athlete Assistant Director of Athletics, Football Volleyball Academic Services Senior Sophomore LISA LAWRENCE DERRYL MYLES KENNEDI MYLES Assistant Director of Academic Services, Assistant Director of Athletics, Student-Athlete Illini Way Student-Athlete Development Video Services Women’s Basketball Sophomore TYRA PERRY MANNY POLLARD DR. CHRISTOPHER SPAN Head Coach Head Coach Faculty Athletics Representative Softball Women’s Diving PAGE 2 BIG TEN CONFERENCE Anti-Hate and Anti-Racism Coalition INDIANA UNIVERSITY STEVE AIRD SCOTT DOLSON ANGEL ESCOBEDO Head Coach Deputy Director of Athletics Head Coach Volleyball Wrestling SAVANNA SPEARS ANTHONY THOMPSON RACE THOMPSON Student-Athlete Senior Associate Athletic Director for Student-Athlete Women’s Swimming & Diving Engagement and Sports Performance Men’s Basketball Junior Junior MATTIE WHITE C. KURT ZORN Senior Associate Athletic Director Faculty Athletics Representative for Academic Services & Excellence, Senior Woman Administrator PAGE 2 PAGE 3 BIG TEN CONFERENCE Anti-Hate and Anti-Racism Coalition UNIVERSITY OF IOWA GARY BARTA JULIUS BRENTS VICKI BROWN ABIR CHAUDHRY Director of Athletics Student-Athlete Head Coach Executive Assistant Football Volleyball Football Sophomore BARBARA BURKE ROZ ELLIS LIZ HOLLINGWORTH CHERYL HARRISON Deputy Director of Athletics, Assistant Coach -

PREVIEW MEDIA Amari Gainer Emmett Rice Hamsah Nasirildeen Tamorrion Terry RECEIVING TACKLES D.J

FLORIDA STATE FOOTBALL TEAM BREAKDOWN MEDIA Basic Offense: Multiple | Basic Defense: 4-3 LETTERWINNERS STARTERS RETURNING (17) STARTERS LOST (7) Returning 41 Offense (6) Offense (5) PREVIEW Offense 17 QB James Blackman RB Cam Akers Defense 21 WR Tamorrion Terry WR Keith Gavin Special Teams 3 WR D.J. Matthews TE Tre’ McKitty Lost 27 OL Brady Scott OL Abdul Bello Offense 15 PREVIEW OL Baveon Johnson OL Ryan Roberts Defense 10 OL Dontae Lucas Special Teams 2 Defense (1) Defense (10) DB Stanford Samuels III STARTERS DT Marvin Wilson Returning 17 NG Robert Cooper Special Teams (1) DT Cory Durden Offense 6 PK Ricky Aguayo TEAM Defense 10 DE Janarius Robinson Special Teams 1 LB Amari Gainer Lost 7 LB Leonard Warner III Offense 5 LB Emmett Rice Defense 1 DB Asante Samuel Jr. Special Teams 1 DB Hamsah Nasirildeen DB Akeem Dent Special Teams (1) COACHES P Tommy Martin RETURNING STATISTICAL LEADERS RUSHING G ATT YDS AVG TD LG YPG Jordan Travis 4 23 228 9.9 3 66 57.0 PASSING G PE C-A-INT PCT. YARDS TDS YPG James Blackman 12 141.98 184-292-11 63.0 2339 17 194.9 REVIEW RECEIVING G REC YDS AVG TD LG YPG Tamorrion Terry 13 60 1188 19.8 9 91 91.4 D.J. Matthews 12 36 355 9.9 3 60 29.6 TACKLES TOTAL (UA-A) TFL SACKS INT PBU FF-FR Hamsah Nasirildeen 101 (61-40) 2.0-8 1.0-7 2 3 3-1 Emmett Rice 72 (40-32) 4.5-16 1.0-10 0 1 0-1 HONORS Amari Gainer 69 (31-38) 7.0-35 3.5-27 0 0 2-1 PLAYERS BY STATE/HOMETOWN Florida (63) Tallahassee: Amari Gainer, Grant Glennon, Marshall Tennessee (3) Boynton Beach: Bryan Robinson; Clearwater: Hilaman; Tampa: Isaiah Bolden, DeCalon -

Acc/School Information

ACC/SCHOOL INFORMATION SHIPPING/MAILING 4512 Weybridge Lane Greensboro, NC 27407 Phone: 336-854-8787 EMAIL All staff member email address: (first initial and last [email protected]) Exceptions: Andy Fledderjohann ([email protected]) TC Gammons ([email protected]) FAX NUMBERS Administrative/Communications/Football.... 336-854-8797 Championships (Olympic Sports) .................. 336-369-1203 Compliance/Student-Athlete Welfare ............ 336-369-0065 Finance/Administration .................................. 336-316-6097 Office of the Commissioner ........................... 336-547-6268 theACC.com TWITTER: @theACC FACEBOOK: facebook.com/theACC INSTAGRAM/SNAPCHAT: @ACCsports BOSTON COLLEGE NC STATE BCEagles.com GoPack.com Twitter: @BCEagles Twitter: @PackAthletics CLEMSON NOTRE DAME ClemsonTigers.com und.com Twitter: @ClemsonTigers Twitter: @FightingIrish DUKE PITT GoDuke.com PittsburghPanthers.com Twitter: @DukeATHLETICS Twitter: @Pitt_ATHLETICS FLORIDA STATE SYRACUSE Seminoles.com Cuse.com Twitter: @Seminoles Twitter: @Cuse GEORGIA TECH VIRGINIA RamblinWreck.com VirginiaSports.com Twitter: @GTAthletics Twitter: @VirginiaSports LOUISVILLE VIRGINIA TECH GoCards.com HokieSports.com Twitter: @GoCards Twitter: @hokiesports MIAMI WAKE FOREST HurricaneSports.com GoDeacs.com Twitter: @MiamiHurricanes Twitter: @DemonDeacons NORTH CAROLINA GoHeels.com Twitter: @GoHeels 2019-20 Atlantic Coast Conference Officers President: Joe Tront, Virginia Tech Vice-President: Peter Brubaker, Wake Forest Secretary-Treasurer: Tricia Bellia, Notre Dame 2019-20