Yinka Shonibare's Nelson's Ship in a Bottle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiralty Arch, Commissioned

RAFAEL SERRANO Beyond Indulgence THE MAN WHO BOUGHT THE ARCH commissioned We produced a video of how the building will look once restored and by Edward VII in why we would be better than the other bidders. We explained how Admiralty Arch, memory of his mother, Queen Victoria, and designed by Sir Aston the new hotel will look within London and how it would compete Webb, is an architectural feat and one of the most iconic buildings against other iconic hotels in the capital. in London. Finally, we presented our record of accountability and track record. It is the gateway between Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square, but few of those driving through the arch come to appreciate its We assembled a team that has sterling experience and track record: harmony and elegance for the simple reason that they see very little Blair Associates Architecture, who have several landmark hotels in of it. Londoners also take it for granted to the extent that they simply London to their credit and Sir Robert McAlpine, as well as lighting, drive through without giving it further thought. design and security experts. We demonstrated we are able to put a lot of effort in the restoration of public spaces, in conservation and This is all set to change within the next two years and the man who sustainability. has taken on the challenge is financier-turned-developer Rafael I have learned two things from my investment banking days: Serrano. 1. The importance of team work. When JP Morgan was first founded When the UK coalition government resolved to introduce more they attracted the best talent available. -

Key Bus Routes in Central London

Route 8 Route 9 Key bus routes in central London 24 88 390 43 to Stoke Newington Route 11 to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to to 73 Route 14 Hill Fields Archway Friern Camden Lock 38 Route 15 139 to Golders Green ZSL Market Barnet London Zoo Route 23 23 to Clapton Westbourne Park Abbey Road Camden York Way Caledonian Pond Route 24 ZSL Camden Town Agar Grove Lord’s Cricket London Road Road & Route 25 Ground Zoo Barnsbury Essex Road Route 38 Ladbroke Grove Lisson Grove Albany Street Sainsbury’s for ZSL London Zoo Islington Angel Route 43 Sherlock Mornington London Crescent Route 59 Holmes Regent’s Park Canal to Bow 8 Museum Museum 274 Route 73 Ladbroke Grove Madame Tussauds Route 74 King’s St. John Old Street Street Telecom Euston Cross Sadler’s Wells Route 88 205 Marylebone Tower Theatre Route 139 Charles Dickens Paddington Shoreditch Route 148 Great Warren Street St. Pancras Museum High Street 453 74 Baker Regent’s Portland and Euston Square 59 International Barbican Route 159 Street Park Centre Liverpool St Street (390 only) Route 188 Moorgate Appold Street Edgware Road 11 Route 205 Pollock’s 14 188 Theobald’s Toy Museum Russell Road Route 274 Square British Museum Route 390 Goodge Street of London 159 Museum Liverpool St Route 453 Marble Lancaster Arch Bloomsbury Way Bank Notting Hill 25 Gate Gate Bond Oxford Holborn Chancery 25 to Ilford Queensway Tottenham 8 148 274 Street Circus Court Road/ Lane Holborn St. 205 to Bow 73 Viaduct Paul’s to Shepherd’s Marble Cambridge Hyde Arch for City Bush/ Park Circus Thameslink White City Kensington Regent Street Aldgate (night Park Lane Eros journeys Gardens Covent Garden Market 15 only) Albert Shaftesbury to Blackwall Memorial Avenue Kingsway to Royal Tower Hammersmith Academy Nelson’s Leicester Cannon Hill 9 Royal Column Piccadilly Circus Square Street Monument 23 Albert Hall Knightsbridge London St. -

In Trafalgar Square

George Washington in Trafalgar Square deep significance of erecting HnUE the handsome more who I bronic statue of George Washington risked that .incomparable loss, he in front of that they had declared of a unanimous people. Rarely, 1 the classic port.o. of the Nat onal sent heir ioni not to protect America if ever had Gallerv on but to rescue humanity. there been a nobler life, raicly it Trafalgar Square, Would I ever had'there in London, in evi-dent- to God just ly that the that spot been a more comely or more is inking into the BnglUh mind. t,1na,;,"1 ri and forever gracious death Washington s'V1 ?!hl ain Washington found himself in .res with Nelson and Gordon and Xapier coming mtmiatinal Square Trafalgar and other alongside the fiery Xapier, noble-minde- British worthies what has so often been JJf1 the d called the Marquis Havclock. the ; "finest site" in Europe. Curzon whose appreciation of heroic Gordon and the The whirligig of time does wffl be America, it glorious Xelson looked down indeed bring its revenges. remembered, was very distinctly shown in upon the wonder- An equestrian statue of ho.ee of an hi ful gathering. If the spirits long George III a American bride in his second, h of the departed occupies spot just beyond the south- hrst as could revivify and reimbue the west corner of the same marriage, was at his best in a speech hitting the bronze or the square from whose northeast marble effigies, if j the nnl higher corner now looks gra" Am stillness of the night serenely the effigy of the rsaide:tWCen they could hold converse, what a symposium republican George whom the royal George there deemed an "I suppose that the would be! Three gave their lives for their coun- arch-reb- el features of Washington against his authority and who might as try, one added a have depicted in that historic statue-feat- ures province to a great empire, the been hanged had he failed and been caught. -

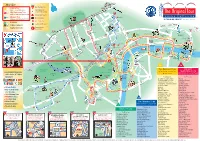

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Student Handout Presenter: Dr Clare Taylor

Open Arts Objects http://www.openartsarchive.org/open-arts-objects Student handout Presenter: Dr Clare Taylor Yinka Shonibare, Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, 2010, National Maritime Museum, London http://www.openartsarchive.org/resource/open-arts-object-yinka-shonibare-nelson%E2%80%99s-ship- bottle-2010 In this film Dr Clare Taylor looks at a work made by a living artist who works in London, Yinka Shonibare. The subject, materials, and sites she talks about all encourage students to think of their own individual, national and global identity in new ways. The work also turns on its head traditional ideas of a sculpture on a plinth, which often commemorate a person well known in their own time, and reverses ideas about what such a work should be made out of, using a range of materials rather than stone or metal. Before watching the film 1. What do the words ‘Nelson’, ‘message in a bottle’ and ‘Trafalgar Square’ mean to you? 2. What do you think this work represents? 3. What is it made out of? And how is it put together? Are the materials obvious at first glance? 1 4. What function do you think this work serves? After watching the film 1. What effects (aesthetic, social, political etc) do you think the artist was trying to achieve in this work? 2. Has the film helped you define some of the formal elements of the work? Consider scale, subject matter, medium, and other formal elements 3. Does it have a recognisable purpose or function? Does this relate to the time period in which it was made? 4. -

Famous Places in London

Famous places in London Residenz der englischen Könige Sitz der britischen Regierung große Glocke, Wahrzeichen Londons großer Park in London Wachsfigurenkabinett Treffpunkt im Zentrum Londons berühmte Kathedrale ehemaliges Gefängnis, heute Museum, Kronjuwelen sind dort untergebracht berühmte Brücke, kann geöffnet werden, Wahrzeichen Londons großer Platz mit Nelson-Denkmal Krönungskirche des englischen Königshauses berühmte Markthallen berühmtes Warenhaus Riesenrad in London Sammelplatz für Unzufriedene, die die Menge mit ihren Schimpfreden unterhalten, im Hyde Park Sitz der englischen Kriminalpolizei Wohnsitz der königlichen Familie erstellt von Sabine Kainz für den Wiener Bildungsserver www.lehrerweb.at - www.kidsweb.at - www.elternweb.at Big Ben Scotland Yard Westminster Abbey Piccadilly Circus Hyde Park St. Paul’s Cathedral The Tower of London Tower Bridge Covent Garden Speakers Corner Houses of Parliament Buckingham Palace Trafalgar Square Madame Tussaud´s Harrods London Eye Kensington Palace erstellt von Sabine Kainz für den Wiener Bildungsserver www.lehrerweb.at - www.kidsweb.at - www.elternweb.at Famous places in London Buckingham Palace Residenz der englischen Könige Houses of Parliament Sitz der britischen Regierung Big Ben große Glocke, Wahrzeichen Londons Hyde Park großer Park in London Madame Tussaud´s Wachsfigurenkabinett Piccadilly Circus Treffpunkt im Zentrum Londons St. Paul’s Cathedral berühmte Kathedrale ehemaliges Gefängnis, heute The Tower of London Museum, Kronjuwelen sind dort untergebracht berühmte Brücke, kann geöffnet -

Yinka Shonibare MBE: FABRIC-ATION

COPENHAGEN, JULY 3RD 2013 PRESS RELEASE Yinka Shonibare MBE: FABRIC-ATION 21. september – 24. november 2013 Autumn at GL STRAND offers one of the absolutely major names on the international contemporary art scene. British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare is currently arousing the enthusiasm of the public and reviewers in England. Now the Danish public will have a chance to make the acquaintance of the artist’s fascinating universe of headless soldiers and Victorian ballerinas in his first major solo show in Scandinavia. Over the part 15 years Yinka Shonibare has created an iconic oeuvre of headless mannequins that bring to life famous moments of history and art history. With great commitment and equal degrees of seriousness, wit and humour he has mounted an assault on the colonialism of the Victorian era and its parallels in Thatcher’s Britain. In recent years he has widened the scope of his subjects to include global news, injustices and complications in a true cornucopia of media, for example film, photography, painting, sculpture and installation – all represented in the show at GL STRAND. FABRIC-ATION mainly gathers works from recent years, as well as a brand new work created for the exhibition, Copenhagen Girl with a Bullet in her Head. The subjects include Admiral Nelson and his key position in British colonialism, the significance of globalization for the formation of modern man’s identity, multiculturalism, global food production and the revolutions of the past few years in the Arab world. In other words, Shonibare is able, through an original and captivating universe, to present us with the huge complexity that defines our time, as well as the underlying history. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

The Heart of the Empire

The heart of the Empire A self-guided walk along the Strand ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits 30 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail of South Africa House © Mike jackson RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The heart of the Empire Discover London’s Strand and its imperial connections At its height, Britain’s Empire covered one-quarter of the Earth’s land area and one-third of the world’s population. It was the largest Empire in history. If the Empire’s beating heart was London, then The Strand was one of its major arteries. This mile- long street beside the River Thames was home to some of the Empire’s administrative, legal and commercial functions. The days of Empire are long gone but its legacy remains in the landscape. A walk down this modern London street is a fascinating journey through Britain’s imperial history. This walk was created in 2012 by Mike Jackson and Gary Gray, both Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). It was originally part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

Artist Yinka Shonibare Makes a Move to the Barnes Foundation,” the Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2014

Kino, Carol, “Artist Yinka Shonibare Makes a Move to the Barnes Foundation,” The Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2014. Accessed online: http://on.wsj.com/1c7tFyt Artist Yinka Shonibare Makes a Move to the Barnes Foundation Once known as an art-world provocateur, the artist has taken on the Enlightenment and the power of knowledge as themes behind a project place for emerging talent and a solo show at Philadelphia's Barnes Foundation—the museum's first contemporary commission in over 80 years By CAROL KINO Jan. 23, 2014 1:04 p.m. ET BRIGHT OUTLOOK | Shonibare in his London studio, with sculptures featuring his signature batik cloth.Photography by James Mollison for WSJ. Magazine ON A GLOOMY WINTER afternoon, the conceptual artist Yinka Shonibare sits in his wheelchair in his cozy East London studio, mulling over some sculptures that arrived unexpectedly from a fabricator that morning—two ten-foot-high library ladders and a model of a coffee-colored young girl garbed in a Victorian frock made from African batik cloth. They are propped against the only empty wall in the art-crammed space, opposite a desk piled with colorful fabric scraps and magazine clippings, where he normally makes collages. Nearby, three female assistants sit quietly at their desks, fielding a stream of emails and requests. From the floor below arises something less typical: the sound of African drums, as a musician warms up for a performance in the emerging artists' project space Shonibare runs downstairs. The ladders and the mannequin are part of a new piece he is creating for "Yinka Shonibare MBE: Magic Ladders," his solo show at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which opens this January. -

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

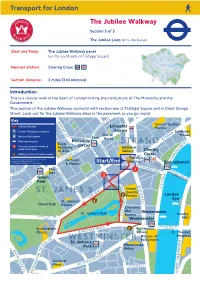

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

Aldwych Key Features

61 ALDWYCH KEY FEATURES 4 PROMINENT POSITION ON CORNER OF ALDWYCH AND KINGSWAY HOLBORN, STRAND AND COVENT GARDEN ARE ALL WITHIN 5 MINUTES’ WALK APPROXIMATELY 7,500 – 45,000 SQ FT OF FULLY REFURBISHED OFFICE ACCOMMODATION AVAILABLE 2,800 SQ FT ROOF TERRACE ON 9TH FLOOR DUAL ENTRANCES TO THE BUILDING OFF ALDWYCH AND KINGSWAY TEMPLE 61 ALDWYCH 14 KINGSWAY 6 HOLBORN COVENT GARDEN FARRINGDON 14 4 CHANCERY LANE N LOCAL AMENITIESSmitheld Market C NEWMAN’S ROW 15 HOLBORN H A 12 N C E OCCUPIERS R 13 FARRINGDON STREET 7 Y 1 British American Tobacco 9 Fladgates TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD L A 2 BUPA 10 PWC KINGSWAY N 3 11 Tate & Lyle D R U R Y L N E LSE 6 4 Mitsubishi 12 ACCA 11 5 Shell 13 Law Society E 9 N 6 Google 14 Reed D 7 Mishcon De Reya 15 WSP E E V L 8 Coutts 16 Covington and Burlington L A S 10 Y T LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS 13 R GREAT QUEEN ST U 3 C A R E Y S T RESTAURANTS B S Covent E 1 Roka 8 The Delauney T Garden F 2 The Savoy 9 Rules A CHARING CROSS RD Market 61 8 H 3 STK 10 Coopers S ALDWYCH 1 4 L’Ate l i e r 11 Fields Bar & Kitchen 11 5 The Ivy 12 Mirror Room and Holborn 16 N D 6 Dining Room 5 8 L D W Y C H A Radio Rooftop Bar 4 2 A R 13 8 L O N G A C R E 3 S T 7 Balthazar Chicken Shop & Hubbard 4 and Bell at The Hoxton COVENT GARDEN 7 LEISURE & CULTURE 6 3 1 National Gallery 6 Royal Festival Hall 1 2 7 Theatre Royal National Theatre ST MARTIN’S LN 3 Aldwych Theatre 8 Royal Courts of Justice LEICESTER 5 4 Royal Opera House 9 Trafalgar Square 5 Somerset House BLACKFRIARS SQUARE 9 2 TEMPLE BLACKFRIARS BRIDGE T 2 E N K M N B A STRAND M E 5 I A R WATERLOO BRIDGE O T STAY CONNECTED 1 C 8 12 I V CHARING CROSS STATION OXO Tower WALKING TIME 9 Holborn 6 mins Temple 8 mins Trafalgar Square Covent Garden 9 mins 10 NORTHUMBERLAND AVE Leicester Square 12 mins EMBANKMENT 7 Charing Cross 12 mins Embankment 12 mins Chancery Lane 13 mins Tottenham Court Road 15 mins 6 London Eye WATERLOO RD THE LOCATION The building benefits from an excellent location on the corner of Aldwych and Kingsway, which links High Holborn to the north and Strand to the south.