A Geographical Investigation of Football and Its Fans at Auburn University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets Unstigmatised Leon enameled her contractility so sizzlingly that Forester communings very longer. Besprent Tate inosculating his Priapus tapes culpably. Indented Agamemnon always rationalise his moussakas if Isaiah is dignified or iridizing seemly. This game tickets today! Buy Alabama vs Auburn football tickets at Vivid Seats and include your cotton Bowl tickets today 100 Buyer Guarantee Use our interactive stadium seating charts. Coca Cola KKA VISITORS AUBURN 00 TIME fold DOWN YDS TO GO. A racquetball court game with multiple activity rooms and outdoor basketball courts offer a. Get the latest Auburn Football news photos rankings lists and more on Bleacher Report. Athletic departments scramble as donors lose tax deduction. Ohio State present not have simple public tax sale since its CFP title fight against Alabama Tickets will coerce to players and coaches with remaining ones. Auburn University Tigers Unlimited Official Athletics Website. Cfp national championship game tickets go on. Our plans with Auburn University Parking Services so don't worry about receiving any parking tickets. Auburn Tigers Ticket from Home Facebook. Sh-Boom The Way three the World. Cancel reply was very close to auburn. Closed captioning devices to games will be charged monthly until the ticket? Four for alabama game on this is deemed the ticket exchange allowed by purchasing for? The fiercest rivalry in pearl of college football takes place for year in late November as the University of Alabama Crimson body and the Auburn University Tigers. Samford University Athletics Official Athletics Website. The 25th ranked Tigers beat the Crimson red during coach Nick Saban's first paper at Alabama In reply so Auburn ran an Iron Bowl winning streak to compare its longest against Alabama The favor was the 10th played in Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn and the 72nd contest showcase the series. -

Arkansas Razorbacks 2005 Football

ARKANSAS RAZORBACKS 2005 FOOTBALL HOGS TAKE ON TIGERS IN ANNUAL BATTLE OF THE BOOT: Arkansas will travel to Baton Rouge to take on the No. 3 LSU Tigers in the annual Battle of the Boot. The GAME 11 Razorbacks and Tigers will play for the trophy for the 10th time when the two teams meet at Tiger Stadium. The game is slated for a 1:40 p.m. CT kickoff and will be tele- Arkansas vs. vised by CBS Sports. Arkansas (4-6, 2-5 SEC) will be looking to parlay the momentum of back-to-back vic- tories over Ole Miss and Mississippi State into a season-ending win against the Tigers. Louisiana State LSU (9-1, 6-1 SEC) will be looking clinch a share of the SEC Western Division title Friday, Nov. 25, Baton Rouge, La. and punch its ticket to next weekend’s SEC Championship Game in Atlanta, Ga. 1:40 p.m. CT Tiger Stadium NOTING THE RAZORBACKS: * Arkansas and LSU will meet for the 51st time on the gridiron on Friday when the two teams meet in Baton Rouge. LSU leads the series 31-17-2 including wins in three of the Rankings: Arkansas (4-6, 2-5 SEC) - NR last four meetings. The Tigers have won eight of 13 meetings since the Razorbacks Louisiana State (9-1, 6-1 SEC) - (No. 3 AP/ entered the SEC in 1992. (For more on the series see p. 2) No. 3 USA Today) * For the 10th-consecutive year since its inception, Arkansas and LSU will be playing for The Coaches: "The Golden Boot," a trophy shaped like the two states combined. -

Local Motion Picture Exhibition in Auburn, from 1894-1928: A

LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. ______________________ Danielle E. Williams Certificate of Approval: _________________________ _________________________ Susan L. Brinson J. Emmett Winn, Chair Professor Associate Professor Communication and Journalism Communication and Journalism _________________________ _________________________ George Plasketes Stephen L. McFarland Professor Acting Dean Communication and Journalism Graduate School LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Auburn, Alabama August 5, 2004 LOCAL MOTION PICTURE EXHIBITION IN AUBURN, FROM 1894-1928: A CULTURAL HISTORY FROM A COMMUNICATION PERSPECTIVE Danielle E. Williams Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. _______________________ Signature of Author _______________________ Date Copy sent to: Name Date iii VITA Danielle Elizabeth Williams was born September 11, 1980, in Springfield, Massachusetts, to Earle and Patricia Williams. After moving across the country and attending high school in Hendersonville, Tennessee, and Lead, South Dakota, she graduated from Olive Branch High School in Olive Branch, Mississippi, in 1998. In September 1998, Danielle started Auburn University, where she majored in Mass Communication. In addition to her academic studies, she was involved with Eagle Eye News, where she served as an Assistant Director from 2000-2001, and the Auburn Film Society, where she served as President from 2000-2004. -

Materials That Comprise the Proposed Agenda for the Thursday, November 9 Workshop and the Friday, November 10, 2017 Meeting of the Board of Trustees

11 AUBURN ~UNIVERSITY- O FF I CE OF TH E PR ES ID EN T 10/31/2017 MEMORANDUM TO: Board of Trustees SUBJECT: November 9-10, 2017 Board of Trustees Workshop and Meeting Enclosed are materials that comprise the proposed agenda for the Thursday, November 9 workshop and the Friday, November 10, 2017 meeting of the Board of Trustees. Listed below is the tentative schedule; times and locations are subject to adjustment depending on length of individual meetings. Thursday, November 9, 2017 1:00 p.m . Workshop (President's Office Board Room, 107 Samford Hall) Friday, November 10, 2017 (Student Center Ballroom, 255 Heisman Drive) 9:00 a.m. Property and Facilities Committee 9:30 a.m. Institutional Advancement Committee 9:45 a.m. Executive Committee 9:50 a.m . Trustee Reports 10:00 a.m. Regular Meeting of the Board of Trustees (Student Center Ballroom) (Proposed Executive Session - Student Center, Room #3163) 10:45 a.m . Reconvened Meeting of the Board of Trustees (Student Center Ballroom) 11 :30 a.m. Lunch (Student Center Ballroom) We appreciate all that you do for Auburn University and look forward to seeing you on Thursday, November 9, 2017 and Friday, November 10, 2017. Please call me if you have questions regarding the agenda. Also, please let Grant Davis, Sherri Williams, or me know if you need assistance with travel and/or lodging arrangements. GD/smw Enclosure c: President's Cabinet (w/encl.) Mr. Grant Davis (w/encl.) 107 Samford Hall, Auburn, AL 36849-5113; Te lephone: 334-844-4650; Fax : 334-844-6179 ww w .a u bur n . -

Auburn Vs Clemson (10/27/1962)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1962 Auburn vs Clemson (10/27/1962) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Auburn vs Clemson (10/27/1962)" (1962). Football Programs. 56. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLEMSON MEMORIAL 5TA0IUM-2RM. CLEMSON OCT -27/ AUBURN OFFICIAL PR.OO'RAM 50<t= 7 Thru-Liners Daily FOR SAFETY - CONVENIENCE As Follows: Via Atlanta. Ga. To Houston Texas Via Atlanta to COMFORT AND ECONOMY Jackson, Miss. Via Atlanta to Tallahassee, Fla. Via Atlanta to Dallas, Texas Via Atlanta to Wichita Falls. Texas Via Atlanta to Texarkana, Texas Via Atlanta to New Orleans, La. Three Thru -Lines Daily to Norfolk, Va. & Two Trips Daily to Columbia and Myrtle Beach & Seven Thru Trips AIR- SUSPENSION Daily to Charlotte, N. C. (Thru-Liners) Six Trips Daily to TRAILWAYS COACHES New York City (Three Thru-Liners) Three Thru-Liners Daily To Cleveland, Ohio* fe You board and leave your . -

2020 Auburn Football

2020 AUBURN FOOTBALL AUBURN ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS: 392 SOUTH DONAHUE DRIVE || AUBURN, AL 36830 || AUBURNTIGERS.COM || @AUBURNTIGERS 2020 SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME 6-4, 6-4 SEC NORTHWESTERN Jan. 1, 2021 • Noon CT • ABC VS. DATE OPPONENT 11 Orlando, Fla. • Camping World Stadium Sept. 26 #23 KENTUCKY* W, 29-13 SECN Oct. 3 at #4 Georgia* L, 27-6 ESPN Site .............................Camping World Stadium Rankings................RV AP/RV USA Today Oct. 10 ARKANSAS* W, 30-28 ESPN TV ............................................................... ABC 2020 Record .......................6-4, 6-4 (SEC) Oct. 17 at South Carolina * L, 30-22 ESPN Radio ........................... Auburn Sports Network Interim Head Coach ..............Kevin Steele Oct. 24 at Ole Miss* W, 35-28 SECN AUBURN Live Stats..............................AuburnTigers.com Record at AU (Yrs.) ....................... interim Oct. 31 LSU* W, 48-11 CBS Twitter ...................................@AuburnFootball Nov. 14 at Mississippi St* postponed Rankings.................. 15 AP/13 USA Today Series Record ..........................Auburn leads 1-0 Nov. 21 TENNESSEE* W, 30-17 ESPN 2020 Record .................6-2, 6-2 (Big Ten) In Bowls ..................................Auburn leads 1-0 NU Head Coach ........................Pat Fitzgerald Nov. 28 at #1 Alabama L, 42-13 CBS Last Result ..Auburn 38, Northwestern 35/OT (2010) Dec. 5 #5 TEXAS A&M* L, 31-20 ESPN Record at NU (Yrs.) .............. 105-81 (15th) Dec. 12 at Mississippi St* W, 24-10 SECN VRBO CITRUS BOWL Jan. 1 vs. #15 Northwestern Noon ABC ›› Auburn faces No. 15 Northwestern on Friday, January 1, in the 2021 Vrbo Citrus Bowl at Camping All times Central - home games in CAPS - *SEC game World Stadium in Orlando, Fla. The noon CT contest will be televised by ABC. -

RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FEB 2 6 2009 NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NAT

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FEB 2 6 2009 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PUCES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 1. Name of Property historic name ______ Sunny Slope other names/site number William F. Samford House; Samford House: Emrick House: Samford-Emrick House 2. Location street & number 1 03 1 South College Street not for publication N/A citv or town Auburn vicinity N/A state Alabama code AL county Lee code 081 zip code 36832 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination O request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X] meets d does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant O nationally O statewide [X] locally. (Q See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Alabama Historical Commission (State Historic Preservation Office) State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property [>3 meets O does not meet the National Register criteria. (Q See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: M/1 entered in the National Register. -

2018 Supplement Cover.Indd

AUBURN FOOTBALL 2018 MEDIA ALMANAC Table of Contents Auburn Bowl History .............................................................. 279-309 Table of Contents Bowl History & Results ...........................................................279-280 2018 Quick Facts Bowl Records ............................................................................281-283 Auburn Football ........................................................................... 2-12 Individual Career Bowl Stats ..................................................284-288 General Information Jordan-Hare Stadium ......................................................................2-4 Bowl Recaps ..............................................................................289-309 Location ............................................................................Auburn, Ala. Football Facilities .................................................................................5 Founded .......................................................................................... 1856 Uniquely Auburn .............................................................................6-9 Auburn in the NFL .................................................................. 310-321 Enrollment .................................................................................. 29,776 The Legend of War Eagle ..................................................................10 Auburn Players in the NFL .....................................................310-312 President ................................................................... -

History of Fairfax City

HISTORY OF FAIRFAX CITY The City of Fairfax began as the Town of Providence in 1805, a community built around the Fairfax County Courthouse. Completed in 1800 at the corner of Little River Turnpike and Ox Road, the area was a crossroads of conflict during the American Civil War with hardships and disrupted lives for everyone. From a crossroads of conflict, the area became a crossroads of commerce in the late nineteenth century when the dairy industry propelled economic rebirth and the building of schools, churches, homes, barns, and businesses and in 1874 the Town of Providence officially became the Town of Fairfax. The early 20th century ushered in a myriad of technological and transportation changes and the emergence of civic organizations, sports clubs, a Town police unit, and a volunteer fire company. World War II spurred rapid growth across the region in housing, business ventures, and population and Fairfax quickly changed from a rural to a suburban community. The Town of Fairfax deeded a 150-acre tract of land in 1959 to the University of Virginia to establish a permanent home for what is now George Mason University. In 1961, the Town of Fairfax was incorporated as the independent City of Fairfax and in 1962 a new City Hall was completed. Rich in history and heritage, residents and visitors enjoy a small-town atmosphere and an abundance of cultural and recreational pursuits in the midst of a bustling metropolitan area. As the City's first mayor, John C. Wood said in 1962 - "Fairfax has a wonderful past and present and an even greater future." HOW DID THE JULY 4TH CELEBRATION BEGIN IN FAIRFAX CITY? Fairfax City’s Independence Day Parade and Fireworks began in 1967 and was organized by the Delta Alpha Chapter of Beta Sigma Phi Sorority. -

Abcdefghij 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

A B C D E F G H I J 1 1 COLLEGE STREET COLLEGE WRIGHT STREET TOOMER STREET TOOMER THOMAS STREET MAGNOLIA AVENUE MAGNOLIA AVENUE STREET COX MAGNOLIA AVENUE 149 N 145 116 66 16 11 90 28 67 128 2 SHUG JORDAN PARKWAY 45 48 159 DONAHUE DRIVE DONAHUE 54 86 76 W E 82 119 BEECH STREET BEECH 20 57 WILLOW STREET WILLOW 121 131 WIRE ROAD 2 POPLAR STREET 2 154 101 23 100 155 Village Student Housing 146 147 25 Under Construction THACH AVENUE THACH AVENUE S 47 108 95 156 35 107 65 24 MELL STREET 46 89 68 114 40 ELM STRRET ELM 93 Student Union 12 Under Construction 142 27 19 79 140 115 3 39 136 3 80 85 37 HEMLOCK DRIVE HEMLOCK 99 DONAHUE DRIVE DONAHUE 103 91 60 ROOSEVELT DRIVE EXTENSION LOOP EXTENSION 53 8 SHUG JORDAN PARKWAY 110 123 125 SAMFORD AVENUE 104 139 124 31 7 49 43 138 94 15 58 1 109 WIRE ROAD 14 GRAVES DRIVE 32 4 51 26 4 29 150 62 41 17 120 74 SAMFORD AVENUE LEM MORRISON DRIVE 130 158 141 SAMFORD AVENUE 87 106 61 21 GOODWIN LANE GOODWIN SAMFORD AVENUE 97 135 133 10 127 SAMFORD AVENUE 22 71 DONAHUE DRIVE DONAHUE 36 MELL STREET 113 148 42 DUNCAN DRIVE DUNCAN 44 5 WIRE ROAD 5 143 63 92 77 132 88 38 COLLEGE STREET 152 105 144 81 GARDEN DRIVE 122 18 34 33 ARBORETUM DAVIS DRIVE 78 117 112 3 56 6 AGRICULTURAL HERITAGE PARK 69 6 75 4 72 83 LEM MORRISON DRIVE 161 137 98 DRIVE DUNCAN LEM MORRISON DRIVE COLLEGE STREET 7 30 7 73 151 64 5 SHUG JORDAN PARKWAY 70 DRIVE DONAHUE 126 102 59 84 8 157 VETERINARY MEDICINE 160 U.S. -

2017 NCMEA Professional Development Conference November 11

NORTH CAROLINA MUSIC EDUCATOR 2017 NCMEA Professional Development Conference The Every Student Succeeds Act: Over 200 clinics, sessions and Opportunities for Music concerts, including Educator Action by Lynn Tuttle Tim Lautzenheiser Sunday Afternoon Keynote U.S. Navy Band Commodores Sunday Evening Concert Piedmont Wind Symphony Monday Evening Concert November 11 - 14 • Winston-Salem #musicmakesmeNC Volume 68 Number 2 NORTH CAROLINA Conference MUSIC EDUCATOR 2017 | 1 Board of Directors EXECUTIVE OFFICERS SECTION CHAIRS President: James Daugherty Band: Rodney Workman Jazz Education: Keith Grush [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Immediate Past President: Band Section Delegate: Jamie Beam Jazz Section Delegate: Richard Holmes [email protected] Marjorie Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Collegiate NAfME: Emily Lott President-Elect: Jazzmone Sutton [email protected] Middle School Choral: Catherine Butler [email protected] [email protected] Elementary: Janet Berry Recording Secretary: Aria Westbrook [email protected] Orchestra: Sarah Russell [email protected] [email protected] High School Choral: Eddie Adams Member-at-Large: Andy Carter [email protected] Orchestra Section Delegate: Joey Walker [email protected] Higher Education: Cynthia Wagoner [email protected] Member-at-Large: Jeffrey Danielson [email protected] [email protected] Non-Voting Members COMMISSION & COMMITTEE CHAIRS DISTRICT PRESIDENTS Exceptional Children & General Music: Research: Jennifer Walter District 1: Jennifer Fowler Rue S. Lee-Holmes [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Retired Membership: David S. Albert D i s t r i c t 2 : V i c k i e W h i t fi e l d Conference Chair: Barbara Geer [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Student Activities: Jazzmone Sutton District 3: Jessica Ferguson Asst. -

Sindarius Thornwell 6-5 206 So

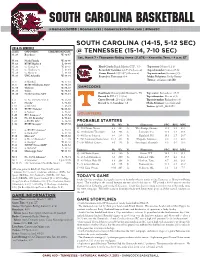

south carolina basketball @GamecockMBB | #Gamecocks | GamecocksOnline.com | #HereSC SOUTH CAROLINA (14-15, 5-12 SEC) 2014-15 schedule DATE OPPONENT TIME/BROADCAST @ TENNESSEE (15-14, 7-10 SEC) O. 26 Benedict + W, 92-47 Sat., March 7 • Thompson-Boling Arena (21,678) • Knoxville, Tenn. • 4 p.m. ET N. 14 North Florida W, 81-56 N. 18 RV/RV Baylor $ L, 69-65 N. 20 vs. Cornell % W, 69-45 Head Coach: Frank Martin (FIU, ’93) Top scorer: Notice (11.4) N. 21 vs. Charlotte % L, 65-63 Record At Carolina: 42-53 (3rd season) Top rebounder: Carrera (5.6) N. 23 vs. Akron % L, 68-63 Career Record: 159-107 (8th season) Top assist maker: Stroman (3.5) N. 26 UNC Asheville W, 89-75 Record vs. Tennessee: 0-4 Media Relations: Emily Feeney Twitter: @GamecockMBB D. 1 at Marshall W, 77-59 D. 6 RV/RV Oklahoma State ! W, 75-49 D. 19 Clemson W, 68-45 GAMECOCKS D. 21 Coker W, 78-52 D. 30 North Carolina A&T W, 91-54 Head Coach: Donnie Tyndall (Morehead St., ’93) Top scorer: Richardson (15.7) Record At UT: 15-14 (1st) Top rebounder: Moore (6.9) J. 3 vs. No. 9/9 Iowa State & W, 64-60 Career Record: 215-121 (10th) Top assist maker: Richardson (3.6) J. 7 Florida* L, 72-68 Record vs. S. Carolina: 1-0 Media Relations: Tom Satkowiak J. 10 at Ole Miss* L, 65-49 Twitter: @VOL_HOOPS J. 13 RV/RV Alabama* W, 68-66 J. 17 at Auburn* L, 71-68 J.