State of the St. George Estuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine

Environmental Assessment Finding of No Significant Impact, and Section 404(b)(1) Evaluation for Maintenance Dredging DRAFT Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine US ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS New England District March 2016 Draft Environmental Assessment: Saco River FNP DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Section 404(b)(1) Evaluation Saco River Saco & Biddeford, Maine FEDERAL NAVIGATION PROJECT MAINTENANCE DREDGING March 2016 New England District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 696 Virginia Rd Concord, Massachusetts 01742-2751 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT HISTORY, NEED, AND AUTHORITY .......................................... 1 3.0 PROPOSED PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................... 3 4.0 ALTERNATIVES ............................................................................................ 6 4.1 No Action Alternative ..................................................................................... 6 4.2 Maintaining Channel at Authorized Dimensions............................................. 6 4.3 Alternative Dredging Methods ........................................................................ 6 4.3.1 Hydraulic Cutterhead Dredge....................................................................... 7 4.3.2 Hopper Dredge ........................................................................................... 7 4.3.3 Mechanical Dredge .................................................................................... -

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

Physicsof Estuariesand Coastal Seas

1 August 12-16 2012 n New York City The Physics of Estuaries and Coastal Seas Symposium 2 3 Assessing Suspended Sediment Dynamics in the San Francisco Bay-Delta System: Coupling Landsat Satellite Imagery, in situ Data and a Numerical Model Fernanda Achete1, Mick van der Wegen1, Dave Schoellhamer2, Bruce E. Jaffe2 1 UNESCO-IHE, Delft, Netherlands 2 U.S. Geological Survey Rivers draining the Central Valley and Sierras of California, including the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, meet in the Delta before discharging into the northeastern end of the San Francisco Estuary. The Bay-Delta system is an important region for a) economic activities (ports, agriculture, and industry), b) human settling (the San Francisco Bay area hosts 7.15 million inhabitants) and c) ecosystems (the Delta area hosts several endemic species and is an important regional breeding and feeding environment). Human activities, including hydraulic mining and agriculture development have affected the Bay-Delta system over the past 150 years. Other examples of anthropogenic influence on the system are damming of rivers, channels dredging, land reclamation and levee construction. Suspended sediment concentration (SSC) has varied considerably as a result of these activities. The change in SSC has a high impact on ecosystems by influencing light penetration that is closely related to primary production, contaminants distribution and marshland development. Better understanding of the spatial distribution and temporal variation of SSC opens the way to improved understanding ecosystem dynamics in the Bay-Delta system and to assess the impact of future developments such as water export, sea level rise and decreasing SSC levels. -

EARTH Title Description ENTITIES ATTRIBUTES DYNAMIC ASPECTS

EARTH Title Description ENTITIES ATTRIBUTES DYNAMIC ASPECTS DIMENSIONS ACCESSORY TERMS <EFFECTS AND SINGLE EVENTS> <STRUCTURE AND MORPHOLOGY> ACTIVITIES COMPOSITION CONDITIONS GENERAL TERMS IMMATERIAL ENTITIES MATERIAL ENTITIES PROCESSES PROPERTIES TIME <ABIOTIC ENVIRONMENT PROCESSES> <BIOECOLOGICAL PROCESSES> <COGNITIVE PROCESSES> <COMPLEX> <MENTAL CONSTRUCTS> <PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROCESSES> <PHYSICAL OPERATIONS> <POLICY ACTIVITIES> <PROCESSES OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS (BY GENERAL TYPE)> <PROCESSES RELATED TO MATERIALS AND PRODUCTS> <PRODUCTIVE SECTORS> <SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES> <SOCIAL, CULTURAL AND POLICY PROCESSES> INDUSTRY LIVING ENTITIES NON LIVING ENTITIES <ABSTRACT CONCEPTS AND PRINCIPLES> <DISPOSAL AND RESTORATION> <KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS> <MANIPULATION, PRODUCTION, CONSUMPTION> <MEASURES> <METHODS AND TECHNIQUES> <PARAMETERS, CRITERIA AND FACTORS> <REPRESENTATION AND ELABORATION SYSTEMS> ARTIFICIAL ENTITIES BIOECOLOGICAL ENTITIES DATA NATURAL ENTITIES NATURAL SPACES BY GENERAL TYPES SOCIAL ENTITIES <ABIOTIC ENVIRONMENT> <BUILT ENVIRONMENT> <EARTH CONSTITUENTS AND MATERIALS> <MATERIALS AND PRODUCTS> <OPEN SPACES, CULTURAL LANDSCAPES> <PARTS> <PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS> <WHOLE> EQUIPMENT AND TECHNOLOGICAL SYSTEMS symbiotic organisms technological systems <ATMOSPHERE ENVIRONMENT> <ECOSYSTEM ABIOTIC COMPONENTS> <EXTRATERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT> <GEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS AND CLIMATIC ZONES> <TERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT> <WATER ENVIRONMENT> <CONTINENTAL WATER ENVIRONMENT> <OCEANIC WATER ENVIRONMENT> <TERRESTRIAL AREAS AND LANDFORMS> geological -

Preparing for Tomorrow's High Tide

Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment for the State of Delaware July 2012 Other Documents in the Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Series A Progress Report of the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee (November 2011) A Mapping Appendix to the Delaware Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment (July 2012) Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment for the State of Delaware Prepared for the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee by the Delaware Coastal Programs of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control i About This Document This Vulnerability Assessment was developed by members of Delaware’s Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee and by staff of the Delaware Coastal Programs section of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. It contains background information about sea level rise, methods used to determine vulnerability and a comprehensive accounting of the extent and impacts that sea level rise will have on 79 resources in the state. The information contained within this document and its appendices will be used by the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee and other stakeholders to guide development of sea level rise adaptation strategies. Users of this document should carefully read the introductory materials and methods to understand the assumptions and trade-offs that have been made in order to describe and depict vulnerability information at a statewide scale. The Delaware Coastal Programs makes no warranty and promotes no other use of this document other than as a preliminary planning tool. This project was funded by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, in part, through a grant from the Delaware Coastal Programs with funding from the Offi ce of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrations, under award number NA11NOS4190109. -

The Maine Area Were Assigned to the Various Forts

The Friendship Sloop "Pemaquid" in Fiberglass LOA - 25' LWL - 21' Beam - 8' 8" DEDICATION Draft - 4' 2" Your editor would like to take it upon himself to dedicate this year's booklet without consulting the POWERS THAT BE. He's sure you have Disp. - 7000 Ibs. noticed the ever increasing quality of this program as years go by. This Keel - 2000 Ibs. is due to the number of contributors of material who have come forward in late years. Instead of writing 90% of the "stuff you read here, he S.A. - 432' now only has to write 10 percent. So to those of you who lend a helping hand — Many thanks! Keep it up! — Don't quit now! — See you next year! and thanks again! President's Message Some time ago some one said, "The only thing that is permanent is This Sloop sleeps four with Galley, Head, Volvo Diesel, Wheel Steering, change." However change for changes sake alone is wrong. Bronze Hardware, Lignum Vitae Blocks and Deadeyes, All Teak Being a member and participating in the activities of the Friendship Woodwork, Native Spruce Spars, and Dacron Sails. Sloop Society is a wonderful experience. The success of the Society is mostly because of the hard work of those who have done so much to HULL AND DECK MOLDING — JARVIS NEWMAN keep up the interest by constantly making changes that are positive im- Southwest Harbor, Maine — (207) 244-3860 provements in the many facets of the Society's activities. As usual these workers are a small percentage of the total member- COMPLETION AND FINISHING — TOMAS D. -

Nonpoint Source Priority Watersheds List MARINE WATERS

Maine Department of Environmental Protection February 2019 Nonpoint Source Priority Watersheds List MARINE WATERS Impaired* Marine Waters Priority List (34 marine waters) Marine Water Area/Town Priority List Reasoning Anthoine Creek & Cove South Portland Negative Water Quality Indicators (FOCB) Broad Cove Cushing DMR/NPS Threat Bunganuc Creek Brunswick CBEP Priority Water Cape Neddick River York MS4 Priority Water Churches Rock So. Thomaston DMR/NPS Threat Egypt Bay Hancock/Franklin DMR/NPS Threat Goosefare Bay Kennebunkport MHB Priority Water, MS4 Priority Water Harpswell Cove Brunswick CBEP Priority Water Harraseeket River Freeport DMR/NPS Threat Hutchins Cove Bagaduce River / DMR/NPS Threat Northern Bay (Penobscot) Hyler Cove Cushing DMR/NPS Threat Kennebunk River Kennebunk MHB Priority Water Little River and Bay Freeport CBEP Priority Water Littlefield Cove Bagaduce River / DMR/NPS Threat Northern Bay (Penobscot) Maquoit Bay Brunswick CBEP Priority Water Martin Cove Lamoine DMR/NPS Threat Medomak River Estuary Waldoboro DMR/NPS Threat Mill Cove South Portland Negative Water Quality Indicators Mill Pond/Parker Head Phippsburg DMR/NPS Threat Mussell Cove Falmouth CBEP Priority Water, DMR/NPS Threat North Fogg Point Freeport CBEP Priority Water Northeast Creek Bar Harbor DMR/NPS Threat Oakhurst Island Harpswell CBEP Priority Water Ogunquit River Estuary Ogunquit MHB Priority Water, DMR/NPS Threat Pemaquid River Bristol DMR/NPS Threat Salt Pond Blue Hill/Sedgwick DMR/NPS Threat, MERI Scarborough River Estuary Scarborough DMR/NPS Threat Spinney Creek Eliot MS4 Priority Water, Negative Water Quality Indicators Spruce Creek Kittery MS4 Priority Water, Negative Water Quality Indicators Page 1 of 2 MDEP NPS Priority Watersheds List – MARINE WATERS February 2019 Marine Water Area/Town Priority List Reasoning Spurwink River Scarborough MHB Priority Water, DMR/NPS Threat St. -

Maine Guide Training

Maine Guide Training 2021 History of Maine Guides ● First hired guides in Maine were Abenaki people who led European explorers, military officials, traders, priests and lumbermen. ● Guiding industry emerged in late 1900s as people in more urban and industrialized regions sought wilderness for recreation ● Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby was first guide licensed in 1897; 1700 others were licensed that year. Maine’s Legal Definition of “Guide” Any person who receives any form of remuneration for his services in accompanying or assisting any person in the fields, forests or on the waters or ice within the jurisdiction of the State while hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, snowmobiling or camping at a primitive camping area. Sea Kayaking Guide Specialization Guides can lead paddlesports trips on the State's territorial seas and tributaries of the State up to the head of tide and out to the three mile limit. This classification includes overnight camping trips in conjunction with those sea-kayaking and paddlesports. Testing Process 1. Criminal Background Check 2. Oral Examination ■ Chart and compass work ■ Catastrophic scenario 3. Written Examination (minimum score of 70 to pass) What Maine Sea Kayak Guides CAn Do ● Lead commercial sea kayaking and SUP trips on Maine’s coastal waters ● Lead overnight camping trips associated with these trips (new as of 2005) ● Lead trips with up to 12 people per guide What Sea Kayak Guides CAN’T Do ● Lead paddling trips on inland waters (by kayak, canoe, SUP or raft) ● Take clients fishing or hunting ● Lead trips that require another type of guide license What are the qualities that you most appreciated in guides you’ve encountered? ● Wilderness Guide Association’s Definition of a Guide A trained and experienced professional with a high level of nature awareness. -

1 | Page Chief, Endangered Species Division April 5, 2020 National

Midwest Biodiversity Institute, Inc. P.O. Box 21561 Columbus, OH 43221-0561 Chief, Endangered Species Division April 5, 2020 National Marine Fisheries Service, F/PR3 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 Re: Application for an Individual Incidental Take Permit (ITP) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 – Lower Kennebec River Fish Assemblage Assessment – REVISED July 1, 2020 III. Contact Information Chris O. Yoder, Research Director Midwest Biodiversity Institute (MBI) 4673 Northwest Parkway Hilliard, OH 43026 (614) 457-6000 x1102 [Main] (614) 403-9592 [Cell] https://midwestbiodiversityinst.org/ Fed. Tax ID #31-1559845 Fish sampling in the Lower Kennebec River drainage by MBI has been conducted annually at seven (7) sites in the Lower Kennebec River mainstem since 2002 and at three (3) sites in the Lower Sebasticook River since 2008. MBI conducted the majority of this work as a grantee or contractor to U.S. EPA and the project was covered by 5-year ITPs issued under Section 7 of the ESA since 2010, the most recent of which expired in 2019. The respective Biological Opinions included annual take limits for Atlantic Sturgeon, Shortnose Sturgeon, and Atlantic Salmon and Terms and Conditions based on Reasonable and Prudent Measures for minimizing harm to individual fish and for reporting any incidental takes to NOAA. The history of incidental takes are included with the descriptions of each of the three ESA listed fish species that are known to occur in the Lower Kennebec River system. IV. Species descriptions: Three ESA listed fish species occur in an approximate 17.5 mile reach of the Lower Kennebec River between the Lockwood Dam and Hydropower Project (operated by Brookfield Inc.) in Waterville, ME to the former Edwards Dam site in Augusta, ME and a 3.5 mile reach of the Lower Sebasticook River downstream from the Benton Falls Dam and Hydropower Project (owned by Benton Falls Associates) to its confluence with the Kennebec River in Winslow, ME. -

Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service V.53

'I', . FISRES OF '!'RE GULF OF MAINE. 101 Description.-The hickory shad differs rather Bay, though it is found in practically all of them. noticeably from the sea herring in that the point This opens the interesting possibility that the of origin of its dorsal fin is considerably in front of "green" fish found in Chesapeake Bay, leave the the mid-length of its trunk; in its deep belly (a Bay, perhaps to spawn in salt water.65 hickory shad 13~ in. long is about 4 in. deep but a General range.-Atlantic coast of North America herring of that length is only 3 in. deep) ; in the fact from the Bay of Fundy to Florida. that its outline tapers toward both snout and tail Occurrence in the Gulf oj Maine.-The hickory in side view (fig. 15); and in that its lower jaw shad is a southern fish, with the Gulf of Maine as projects farther beyond the upper when its mouth the extreme northern limit to its range. It is is closed; also, by the saw-toothed edge of its belly. recorded in scientific literature only at North Also, it lacks the cluster of teeth on the roof of the· Truro; at Provincetown; at Brewster; in Boston mouth that is characteristic of the herring. One Harbor; off Portland; in Casco Ba3T; and from the is more likely to confuse a hickory shad with a shad mouth of the Bay of Fundy (Huntsman doubts or with the alewives, which it resembles in the this record), and it usually is so uncommon within position of its dorsal fin, in the great depth of its our limits that we have seen none in the Gulf body, in its saw-toothed belly and in the lack of ourselves. -

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] Or [email protected]

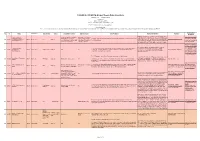

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] or [email protected] ESCAP Statistics Division: [email protected] Acknowledgments The author is thankful for the pre-research done by Michael Bordt (Global Ocean Accounts Partnership co-chair) and Yilun Luo (ESCAP), the contribution from Feixue Li (Nanjing University) and suggestions from Teerapong Praphotjanaporn (ESCAP). Introduction No. ID Name Component Data format Status Acquisition method Data resolution Data Available Further information Website Document CMECS is designed for use within all waters ranging from the Includes the physical, biological, Not limited to specific gear https://iocm.noaa.gov/c Coastal and Marine head of tide to the limits of the exclusive economic zone, and and chemical data that are types or to observations A comprehensive national framework for organizing information about coasts and oceans and mecs/documents/CME 001 SU-001 Ecological Classification Single Spatial units N/A Ongoing from the spray zone to the deep ocean. It is compatible with https://iocm.noaa.gov/cmecs/ collectively used to define coastal made at specific spatial or their living systems. CS_One_Page_Descrip Standard(CMECS) many existing upland and wetland classification standards and and marine ecosystems temporal resolutions tion-20160518.pdf can be used with most if not all data collection technologies. https://www.researchga te.net/publication/32889 The Combined Biotope Classification Scheme (CBiCS) 1619_Combined_Bioto Combined Biotope It is a hierarchical classification of marine biotopes, including aquatic setting, biogeographic combines the core elements of the CMECS habitat pe_Classification_Sche 002 SU-002 Classification Single Spatial units Onlline viewer Ongoing N/A N/A setting, water column component, substrate component, geoform component, biotic http://www.cbics.org/about/ classification scheme and the JNCC/EUNIS biotope me_CBiCS_A_New_M Scheme(SBiCS) component, morphospecies component.