Head Coach's Authority to Hire Assistant Coaches and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

Sun Devil Legends

SUN DEVIL LEGENDS over North Carolina. Local sports historians point to that game as the introduction of Arizona State Frank Kush football to the national scene. Five years later, the Sun Devils again capped an undefeated season by ASU Coach, 1958-1979 downing Nebraska, 17-14. The win gave ASU a No. In 1955, Hall of Fame coach Dan Devine hired 2 national ranking for the year, and ushered ASU Frank Kush as one of his assistants at Arizona into the elite of college football programs. State. It was his first coaching job. Just three years • The success of Arizona State University football later, Kush succeeded Devine as head coach. On under Frank Kush led to increased exposure for the December 12, 1995 he joined his mentor and friend university through national and regional television in the College Football Hall of Fame. appearances. Evidence of this can be traced to the Before he went on to become a top coach, Frank fact that Arizona State’s enrollment increased from Kush was an outstanding player. He was a guard, 10,000 in 1958 (Kush’s first season) to 37,122 playing both ways for Clarence “Biggie” Munn at in 1979 (Kush’s final season), an increase of over Michigan State. He was small for a guard; 5-9, 175, 300%. but he played big. State went 26-1 during Kush’s Recollections of Frank Kush: • One hundred twenty-eight ASU football student- college days and in 1952 he was named to the “The first three years that I was a head coach, athletes coached by Kush were drafted by teams in Look Magazine All-America team. -

Download Book < Articles on Butler Bulldogs Men's

V8URSFQAU5UW Kindle Articles On Butler Bulldogs Men's Basketball Coaches, including: Tony Hinkle, Harlan Page,... A rticles On Butler Bulldogs Men's Basketball Coach es, including: Tony Hinkle, Harlan Page, Th ad Matta, Jay Joh n, Edgar W ingard, Todd Lickliter, Barry Collier (basketball Coach ), Brad Stevens, Jeff Mey Filesize: 2.22 MB Reviews Very useful to all category of individuals. It is one of the most amazing publication i have got read through. You will not feel monotony at anytime of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for about when you question me). (Mr. Johnathon Dach) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 8WQO8JUMCQDB \\ PDF ~ Articles On Butler Bulldogs Men's Basketball Coaches, including: Tony Hinkle, Harlan Page,... ARTICLES ON BUTLER BULLDOGS MEN'S BASKETBALL COACHES, INCLUDING: TONY HINKLE, HARLAN PAGE, THAD MATTA, JAY JOHN, EDGAR WINGARD, TODD LICKLITER, BARRY COLLIER (BASKETBALL COACH), BRAD STEVENS, JEFF MEY To read Articles On Butler Bulldogs Men's Basketball Coaches, including: Tony Hinkle, Harlan Page, Thad Matta, Jay John, Edgar Wingard, Todd Lickliter, Barry Collier (basketball Coach), Brad Stevens, Je Mey eBook, remember to follow the web link below and save the file or have access to additional information that are related to ARTICLES ON BUTLER BULLDOGS MEN'S BASKETBALL COACHES, INCLUDING: TONY HINKLE, HARLAN PAGE, THAD MATTA, JAY JOHN, EDGAR WINGARD, TODD LICKLITER, BARRY COLLIER (BASKETBALL COACH), BRAD STEVENS, JEFF MEY book. Hephaestus Books, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication -

2010-11 NCAA Men's Basketball Records

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............... 2 Division I Coaching Records ..................... 3 Division II Coaching Records .................... 24 Division III Coaching Records ................... 26 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS All-Divisions Coaching Records Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section have been Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee on Infractions to forfeit 44. Don Meyer (Northern Colo. 1967) Hamline 1973-75, or vacate particular regular-season games or vacate particular NCAA tourna- Lipscomb 76-99, Northern St. 2000-10 ........................... 38 923 324 .740 ment games. The adjusted records for these coaches are listed at the end of 45. Al McGuire (St. John’s [NY] 1951) Belmont Abbey the longevity records in this section. 1958-64, Marquette 65-77 .................................................... 20 405 143 .739 46. Jim Boeheim (Syracuse 1966) Syracuse 1977-2010* ..... 34 829 293 .739 47. David Macedo (Wilkes 1996) Va. Wesleyan 2001-10* ... 10 215 76 .739 48. Phog Allen (Kansas 1906) Baker 1906-08, Haskell 1909, Coaches by Winning Percentage Central Mo. 13-19, Kansas 08-09, 20-56 .......................... 48 746 264 .739 49. Emmett D. Angell (Wisconsin) Wisconsin 1905-08, (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching seasons at NCAA Oregon St. 09-10, Milwaukee 11-14 ................................. 10 113 40 .739 schools regardless of classification.) 50. Everett Case (Wisconsin 1923) North Carolina St. 1947-65 ................................................... 19 377 134 .738 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. * active; # Keogan’s winning percentage includes three ties. 1. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, Long Island 32-43, 46-51 ...................................................... -

2016 SUMMER NC Ccach.Pdf

North Carolina Coaches Association N.C. COACH Volume 21, Number 2, summer 2016 From the Clinic Desk by Mac Morris n the spirit of trying to react to the you can enlighten us, we certainly can suggestion said that if you didn’t without attending a session, the lines will criticism leveled in the survey, I will address these in future newsletters. The attend the sessions with the be long. It was suggested that we have try not to be an old man moaning suggestion that we include a section of coaches speaking, you couldn’t sessions on topics other that X’s and O’s. andI groaning and being negative. As I frequently-asked questions is a good one Aattend the rules session. It is a little We have tried this in the past and no one have written numerous times, the title and we probably should try to imple- discouraging to see 200 coaches in a ses- showed up for these sessions. I remember “coach” is very important to me. Any ad- ment this. sion and then 750 in the rules session, a session about teaching the learning- vice I could give to continue this legacy but I’m afraid we couldn’t police that. disabled athlete where 500 coaches were was the purpose of the columns. I can’t oncerns about the Clinic were Another survey responder suggested in the previous session and fewer than 20 help being an old man, but I will try not that the sound system in the Pa- we ask coaches for speaker suggestions; stayed for this topic. -

Texas A&M Men's Basketball

Texas A&M Men's Basketball Game #24: Feb. 11 at Florida (Exactech Arena) Texas A&M Media Relations • www. 12thMan.com Men's Basketball Contact: Adam Quisenberry / E-Mail: [email protected] / O: (979) 862-5453/ C: (713) 582-5135 Media Coverage #17 TELEVISION ..................................................................ESPN2 Florida Texas A&M Tom Hart ................................................................ Play-by-Play Gators Aggies Kara Lawson Barling ..........................................Commentary RADIO..........................................................WTAW 1620 AM Dave South ............................................................ Play-by-Play Mike Caruso ..........................................................Commentary Record ..................................................19-5 (9-2 SEC) Record ............................................13-10 (5-6 SEC) Ranking...................................... No. 17 (AP & USAT) Ranking.......................................................................NR SATELLITE RADIO .................Sirius Ch. 136 / XM Ch. 190 Streak ................................................................... Won 5 Streak ................................................................Win 2 LIVE AUDIO/STATS ............................... 12thMan.com/Live Last 5 / Last 10 ..............................................5-0 / 8-2 Last 5 / Last 10 ..........................................3-2 / 5-5 At Home (In SEC Play) ................................6-1 (5-1) On the -

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 A.M

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 a.m. ET ............Al Skinner, Boston College 10:40 a.m. ET ............Oliver Purnell, Clemson 10:50 a.m. ET ............Mike Krzyzewski, Duke 11:00 a.m. ET ............Leonard Hamilton, Florida State 11:10 a.m. ET ............Paul Hewitt, Georgia Tech 11:20 a.m. ET ............Gary Williams, Maryland 11:30 a.m. ET ............Frank Haith, Miami 11:40 a.m. ET ............Roy Williams, North Carolina 11:50 a.m. ET ............Sidney Lowe, N.C. State 12:00 p.m. ET ............Tony Bennett, Virginia 12:10 p.m. ET ............Seth Greenberg, Virginia Tech 12:20 p.m. ET ............Dino Gaudio, Wake Forest ATLANTIC 10 CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 15) 10:10 a.m. ET ............Bobby Lutz, Charlotte 10:17 a.m. ET ............Chris Mooney, Richmond 10:24 a.m. ET ............Chris Mack, Xavier 10:31 a.m. ET ............Mark Schmidt, St. Bonaventure 10:38 a.m. ET ............Brian Gregory, Dayton 10:45 a.m. ET ............John Giannini, La Salle 10:52 a.m. ET ............Fran Dunphy, Temple 10:59 a.m. ET ............Derek Kellogg, Massachusetts 11:06 a.m. ET ............Karl Hobbs, George Washington 11:13 a.m. ET ............Ron Everhart, Duquesne 11:20 a.m. ET ............Rick Majerus, Saint Louis 11:27 a.m. ET ............Jared Grasso, Fordham 11:34 a.m. ET ............Jim Baron, Rhode Island 11:41 a.m. ET ............Phil Martelli, Saint Joseph’s BIG EAST CONFERENCE Thursday (Jan. 7, Jan. 21, Feb. 4, Feb. 18) 11:00 a.m. ET ............Jay Wright, Villanova 11:08 a.m. -

The BG News October 22, 1982

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-22-1982 The BG News October 22, 1982 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 22, 1982" (1982). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4053. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4053 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■ Tfie Wither Partly cloudy today. High in the mid 40s. Clear and good cold tonight. Low in the morning BG News mid 20s. Friday, Bowling Green State University October 22, 1982 Harshman residents suffering peer harrassment by Judy Roach added. rassment involved destruction of made in the investigation. women's rooms were vandalized, a Wednesday, Oct.20. and "Things have reporter According to freshman Karen Ce- property. On Oct. 11, shampoo and "It is now a matter of a process of 24-hour guard was posted in the hall- been pretty quiet," Cecora added. cora, the harassment has been di- lotion were splashed over the wom- elimination," Bess said. way, Cecora said. Margie Potapchuck, Chapman Hall A complaint of apparent ha- rected toward four women on the en's desks and bookshelves in their Bess would not comment on how when asked who posted the guard in manager, refused to comment on any rassment involving four Chapman floor. -

Mega Conferences

Non-revenue sports Football, of course, provides the impetus for any conference realignment. In men's basketball, coaches will lose the built-in recruiting tool of playing near home during conference play and then at Madison Square Garden for the Big East Tournament. But what about the rest of the sports? Here's a look at the potential Missouri Pittsburgh Syracuse Nebraska Ohio State Northwestern Minnesota Michigan St. Wisconsin Purdue State Penn Michigan Iowa Indiana Illinois future of the non-revenue sports at Rutgers if it joins the Big Ten: BASEBALL Now: Under longtime head coach Fred Hill Sr., the Scarlet Knights made the Rutgers NCAA Tournament four times last decade. The Big East Conference’s national clout was hurt by the defection of Miami in 2004. The last conference team to make the College World Series was Louisville in 2007. After: Rutgers could emerge as the class of the conference. You find the best baseball either down South or out West. The power conferences are the ACC, Pac-10 and SEC. A Big Ten team has not made the CWS since Michigan in 1984. MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY Now: At the Big East championships in October, Rutgers finished 12th out of 14 teams. Syracuse won the Big East title and finished 14th at nationals. Four other Big East schools made the Top 25. After: The conferences are similar. Wisconsin won the conference title and took seventh at nationals. Two other schools made the Top 25. MEN’S GOLF Now: The Scarlet Knights have made the NCAA Tournament twice since 1983. -

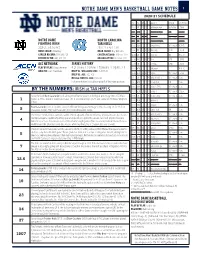

Notre Dame Men's Basketball Game Notes 1 2020-21 Schedule

NOTRE DAME MEN'S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES 1 2020-21 SCHEDULE Date Day AP C Opponent Network Time/Result 11/28 SAT 13 12 at Michigan State Big Ten Net L, 70-80 12/2 WED Western Michigan RSN canceled 12/4 FRI 13 14 Tennessee ACC Network canceled NOTRE DAME NORTH CAROLINA 12/5 SAT Purdue Fort Wayne canceled FIGHTING IRISH TAR HEELS 12/6 SUN Detroit Mercy ACC Network W, 78-70 2020-21: 3-5, 0-2 ACC 2020-21: 5-4, 0-2 ACC HEAD COACH: Mike Brey HEAD COACH: Roy Williams 12/8 TUE 22 20 & Ohio State ESPN2 L, 85-90 CAREER RECORD: 539-290 / 26 CAREER RECORD: 890-257 / 33 12/12 SAT Kentucky CBS W, 64-63 RECORD AT ND: 440-238 / 21 RECORD AT UNC: 472-156 / 18 12/16 THU 21 23 * Duke ESPN L, 65-75 ACC NETWORK SERIES HISTORY 12/19 SAT ^ vs. Purdue ESPN2 L, 78-88 PLAY BY PLAY: Doug Sherman 8-25 | Home: 3-5 | Away: 1-7 | Neutral: 4-13 | ACC: 3-8 12/23 WED Bellarmine W, 81-70 ANALYST: Cory Alexander BREY VS. WILLIAMS/UNC: 4-10/4-10 BREY VS. ACC: 102-106 12/30 WED 23 24 * Virginia ACC Network L, 57-66 ND ALL-TIME VS. ACC: 169-212 1/2 SAT * at North Carolina ACC Network 4 p.m. Full series history available on page 5 of this notes package 1/6 WED * Georgia Tech RSN 7 p.m. 1/10 SUN 24 * at Virginia Tech ACC Network 6 p.m. -

Nevada Men's Basketball

NEVADA MEN’S BASKETBALL VS. NEVADA FLORIDA WOLF PACK GATORS 29-4 19-15 2018-19 NEVADA RADIO/TV ROSTER — GAME NOTES #0 • TRE’SHAWN THURMAN #1 • JALEN HARRIS #2 • COREY HENSON #5 • NISRÉ ZOUZOUA #10 • CALEB MARTIN Forward • 6-8 • 225 • Senior • Transfer Guard • 6-5 • 195 • Junior • Transfer Guard • 6-3 • 175 • Senior • Transfer Guard • 6-3 • 195 • Junior • Transfer Guard • 6-7 • 200 • Senior • 1L #11 • CODY MARTIN #12 • JOJO ANDERSON #14 • LINDSEY DREW #15 • TREY PORTER #20 • DAVID CUNNINGHAM Guard• 6-7 • 200 • Senior • 1L Guard • 6-3 • 185 • Junior • Transfer Guard • 6-4 • 180 • Senior • 2L Forward • 6-11 • 230 • Senior • Transfer Guard • 6-4 • 195 • Senior • SQ #21 • JORDAN BROWN #22 • JAZZ JOHNSON #23 • JALEN TOWNSELL #24 • JORDAN CAROLINE #42 • K.J. HYMES Forward • 6-11 • 210 • Freshman Guard • 5-10 • 180 • Junior • Transfer Guard • 6-7 • 235 • Freshman • HS Forward • 6-7 • 235 • Senior • 2L Forward • 6-10 • 210 • Freshman ERIC MUSSELMAN ANTHONY RUTA GUS ARGENAL BRANDON DUNSON REX WALTERS Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Special Assistant NEVADA WOLF PACK 2018-19 MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES 8 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES 21 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS 14 NBA DRAFT PICKS | 5 ALL-AMERICANS TRACK THE PACK VS. FLORIDA - THURSDAY, MARCH 21 - 3:50 P.M. PT | TNT TNT • Kevin Harlan (Play-By-Play) • Reggie Miller (Analyst) • Dan Bonner (Analyst) • Dana Jacobson (Sideline) ON RADIO Wolf Pack Radio Network - 94.5 FM, 630 AM Pregame starts 30 minutes prior to tip-off • John Ramey (Play-By-Play) • Len Stevens (Analyst) NO. 20 NEVADA WOLF PACK FLORIDA GATORS NCAA West Region Record: ..................29-4 (15-3 MW) Record: ..................19-15 (9-9 SEC) March 21 & 23 Westwood One Last game: ..........................L, 65-56 Last game: ........................ -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31).