Narrative and Number in Busby Berkeley's Footlight Parade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Boxoffice Records: Season 1937-1938 (1938)

' zm. v<W SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL JANET DOUGLAS PAULETTE GAYNOR FAIRBANKS, JR. GODDARD in "THE YOUNG IN HEART” with Roland Young ' Billie Burke and introducing Richard Carlson and Minnie Dupree Screen Play by Paul Osborn Adaptation by Charles Bennett Directed by Richard Wallace CAROLE LOMBARD and JAMES STEWART in "MADE FOR EACH OTHER ” Story and Screen Play by Jo Swerling Directed by John Cromwell IN PREPARATION: “GONE WITH THE WIND ” Screen Play by Sidney Howard Director, George Cukor Producer DAVID O. SELZNICK /x/HAT price personality? That question is everlastingly applied in the evaluation of the prime fac- tors in the making of motion pictures. It is applied to the star, the producer, the director, the writer and the other human ingredients that combine in the production of a motion picture. • And for all alike there is a common denominator—the boxoffice. • It has often been stated that each per- sonality is as good as his or her last picture. But it is unfair to make an evaluation on such a basis. The average for a season, based on intakes at the boxoffices throughout the land, is the more reliable measuring stick. • To render a service heretofore lacking, the publishers of BOXOFFICE have surveyed the field of the motion picture theatre and herein present BOXOFFICE RECORDS that tell their own important story. BEN SHLYEN, Publisher MAURICE KANN, Editor Records is published annually by Associated Publica- tions at Ninth and Van Brunt, Kansas City, Mo. PRICE TWO DOLLARS Hollywood Office: 6404 Hollywood Blvd., Ivan Spear, Manager. New York Office: 9 Rockefeller Plaza, J. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

The American Film Musical and the Place(Less)Ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’S “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis

humanities Article The American Film Musical and the Place(less)ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’s “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis Florian Zitzelsberger English and American Literary Studies, Universität Passau, 94032 Passau, Germany; fl[email protected] Received: 20 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 19 May 2019 Abstract: This article looks at cosmopolitanism in the American film musical through the lens of the genre’s self-reflexivity. By incorporating musical numbers into its narrative, the musical mirrors the entertainment industry mise en abyme, and establishes an intrinsic link to America through the act of (cultural) performance. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and its recent application to the genre of the musical, I read the implicitly spatial backstage/stage duality overlaying narrative and number—the musical’s dual registers—as a means of challenging representations of Americanness, nationhood, and belonging. The incongruities arising from the segmentation into dual registers, realms complying with their own rules, destabilize the narrative structure of the musical and, as such, put the semantic differences between narrative and number into critical focus. A close reading of the 1972 film Cabaret, whose narrative is set in 1931 Berlin, shows that the cosmopolitanism of the American film musical lies in this juxtaposition of non-American and American (at least connotatively) spaces and the self-reflexive interweaving of their associated registers and narrative levels. If metalepsis designates the transgression of (onto)logically separate syntactic units of film, then it also symbolically constitutes a transgression and rejection of national boundaries. In the case of Cabaret, such incongruities and transgressions eventually undermine the notion of a stable American identity, exposing the American Dream as an illusion produced by the inherent heteronormativity of the entertainment industry. -

The Conqueror Hollywood Fallout

A WILLIAM NUNEZ DOCUMENTARY THE CONQUEROR HOLLYWOOD FALLOUT THE CONQUEROR 1 DISCLAIMER: The information provided is for information purposes only. The content is not, and should not be deemed to be an offer of, or invitation to engage in any investment activity. This should not be construed as advice, or a personal recommendation by Red Rock Entertainment Ltd. Red Rock Entertainment Ltd is not authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The content of this promotion is not authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Reliance on the promotion for the purpose of engaging in any investment activity may expose an individual to a significant risk of losing all of the investment. UK residents wishing to participate in this promotion must fall into the category of sophisticated investor or high net worth individual as outlined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). THE CONQUEROR A WILLIAM NUNEZ DOCUMENTARY CONTENTS 4 History 5 Synopsis 7 Downwinders 8 Themes| Research - Interview Subjects - Visual 9 Narrator 10 Director’s Statement 11 Writer | Director 12 | 13 Production Companies 15 Executive Producers 16 Post- Production Company 17 Equity 18 | 19 EIS 20 | 21 Perk & Benefits 22 Press and Reference Links THE HISTORY “IT HAS GONE INTO OUR DNA. I’VE LOST COUNT OF THE FRIENDS I’VE BURIED. I’M NOT PATRIOTIC. MY GOVERNMENT LIED TO ME!” - ST. GEORGE UTAH RESIDENT, 2015 The story of a failed Hollywood epic and the devasting repercussions it had, not only on some of Hollywood’s most iconic stars, but the residents of a desert town in Utah where the film was shot. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

The Museum of Modern Art Announces Holiday Hours and Special Programming for the Holiday Season

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ANNOUNCES HOLIDAY HOURS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMMING FOR THE HOLIDAY SEASON MoMA Will Open One Hour Early December 26–December 31 Lantern Slide Shows on November 30 & December 1 Joan Blondell Film Retrospective, December 19–31 New York, November 27, 2007—The Museum of Modern Art announces special holiday hours and programming this holiday season, including longer hours during Christmas week and a new information desk specifically geared to families with younger visitors. The Museum presents a special showing of a Victorian-era entertainment with a lantern-slide shows for adults and children on November 30 and December 1, as well as daily screenings of classic Hollywood films featuring Joan Blondell from December 19 through 31. Special exhibitions featuring the rarely exhibited drawings of Georges Seurat and the contemporary sculpture of Martin Puryear are on view through the holiday season, and a major exhibition of the etchings of British artist Lucian Freud opens on December 16. MoMA is located in midtown Manhattan, just steps from Fifth Avenue, Rockefeller Center, and Radio City Music Hall. HOLIDAY HOURS AND ADMISSION To accommodate holiday visitors, The Museum of Modern Art will be open one hour earlier than usual—at 9:30 a.m.—from December 26 through January 1. In addition, the museum will be open on New Year’s Day, Tuesday, January 1. Holiday Hours: December 24, 10:30 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Closed December 25. December 26 and 27: 9:30 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. December 28: 9:30 a.m. - 8:00 p.m. -

Radioclassics (Siriusxm Ch. 148) Gregbellmedia

SHOW TIME RadioClassics (SiriusXM Ch. 148) gregbellmedia.com June 21st - June 27th, 2021 SHOW TIME PT ET MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY PT ET 9pm 12mid Mary Livingstone B-Day Fibber McGee & Molly I Was A Communist More Peter Lorre B-Day Frontier Town 10/24/52 Dimension X Family Theatre 7/8/53 9pm 12mid Prev Jack Benny Prgm 2/23/47 From October 10th, 1944 For The FBI 5/7/52 on Fred Allen Show 1/3/43 The Cisco Kid 3/31/53 "The Embassy" 6/3/50 CBS Radio Workshp 8/17/56 Prev Night Night Jack Benny Prgm 9/21/52 Burns & Allen Show 5/18/43 Gangbusters 8/16/52 on Duffy's Tavern 10/19/43 Broadway's My Beat 4/21/50 X-Minus One 8/29/57 Broadway Is My Beat Dragnet Big Guilt 11/23/52 Black Museum 11/25/52 Casey, Crime Photog 1/8/48 Inner Sanctum 3/7/43 Calling All Cars 9/7/37 Burns & Allen 3/27/47 From Dec. 31st, 1949 Big Town 6/18/42 Suspense 6/14/45 Sherlock Holmes 3/31/47 Suspense 7/20/44 Great Gildersleeve 3/1/50 Gunsmoke Belle's Back 9/9/56 11pm 2am Phil Harris Birthday (1) Phil Harris Birthday (2) Mr District Attorney 11/30/52 Paul Frees Birthday (1) Yours Truly, Johnny Boston Blackie 77th Annv Lux Radio's (9/26/38) 11pm 2am Prev Harris & Faye 12/11/53 From Harris & Faye Show Sam Spade 8/2/48 The Whistler 5/22/49 Dollar Marathon Jan 1956 w/ Chester Morris 7/28/44 Seven Keys To Baldpate Prev Night Night Harris & Faye 10/19/52 11/13/49 & 1/13/52 Dimension X 7/12/51 EscapeHouseUsher 10/22/47 The Flight Six Matter w/ Dick Kollmar 1/29/46 with Jack & Mary Benny Harris & Faye 1/15/50 On Suspense 5/10/51 X Minus One 4/24/57 -

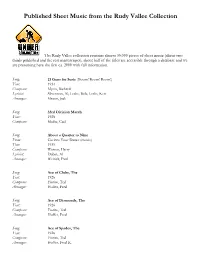

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) -

Mervyn Leroy GOLD DIGGERS of 1933 (1933), 97 Min

January 30, 2018 (XXXVI:1) Mervyn LeRoy GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933 (1933), 97 min. (The online version of this handout has hot urls.) National Film Registry, 2003 Directed by Mervyn LeRoy Numbers created and directed by Busby Berkeley Writing by Erwin S. Gelsey & James Seymour, David Boehm & Ben Markson (dialogue), Avery Hopwood (based on a play by) Produced by Robert Lord, Jack L. Warner, Raymond Griffith (uncredited) Cinematography Sol Polito Film Editing George Amy Art Direction Anton Grot Costume Design Orry-Kelly Warren William…J. Lawrence Bradford him a major director. Some of the other 65 films he directed were Joan Blondell…Carol King Mary, Mary (1963), Gypsy (1962), The FBI Story (1959), No Aline MacMahon…Trixie Lorraine Time for Sergeants (1958), The Bad Seed (1956), Mister Roberts Ruby Keeler…Polly Parker (1955), Rose Marie (1954), Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), Quo Dick Powell…Brad Roberts Vadis? (1951), Any Number Can Play (1949), Little Women Guy Kibbee…Faneul H. Peabody (1949), The House I Live In (1945), Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo Ned Sparks…Barney Hopkins (1944), Madame Curie (1943), They Won't Forget (1937) [a Ginger Rogers…Fay Fortune great social issue film, also notable for the first sweatered film Billy Bart…The Baby appearance by his discovery Judy Turner, whose name he Etta Moten..soloist in “Remember My Forgotten Man” changed to Lana], I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), and Two Seconds (1931). He produced 28 films, one of which MERVYN LE ROY (b. October 15, 1900 in San Francisco, was The Wizard of Oz (1939) hence the inscription on his CA—d.