Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL UCLA FOOTBALL AWARDS Henry R

2005 UCLA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE NON-PUBLISHED SUPPLEMENT UCLA CAREER LEADERS RUSHING PASSING Years TCB TYG YL NYG Avg Years Att Comp TD Yds Pct 1. Gaston Green 1984-87 708 3,884 153 3,731 5.27 1. Cade McNown 1995-98 1,250 694 68 10,708 .555 2. Freeman McNeil 1977-80 605 3,297 102 3,195 5.28 2. Tom Ramsey 1979-82 751 441 50 6,168 .587 3. DeShaun Foster 1998-01 722 3,454 260 3,194 4.42 3. Cory Paus 1999-02 816 439 42 6,877 .538 4. Karim Abdul-Jabbar 1992-95 608 3,341 159 3,182 5.23 4. Drew Olson 2002- 770 422 33 5,334 .548 5. Wendell Tyler 1973-76 526 3,240 59 3,181 6.04 5. Troy Aikman 1987-88 627 406 41 5,298 .648 6. Skip Hicks 1993-94, 96-97 638 3,373 233 3,140 4.92 6. Tommy Maddox 1990-91 670 391 33 5,363 .584 7. Theotis Brown 1976-78 526 2,954 40 2,914 5.54 7. Wayne Cook 1991-94 612 352 34 4,723 .575 8. Kevin Nelson 1980-83 574 2,687 104 2,583 4.50 8. Dennis Dummit 1969-70 552 289 29 4,356 .524 9. Kermit Johnson 1971-73 370 2,551 56 2,495 6.74 9. Gary Beban 1965-67 465 243 23 4,087 .522 10. Kevin Williams 1989-92 418 2,348 133 2,215 5.30 10. Matt Stevens 1983-86 431 231 16 2,931 .536 11. -

Negro League Teams

From the Negro Leagues to the Major Leagues: How and Why Major League Baseball Integrated and the Impact of Racial Integration on Three Negro League Teams. Christopher Frakes Advisor: Dr. Jerome Gillen Thesis submitted to the Honors Program, Saint Peter's College March 28, 2011 Christopher Frakes Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Kansas City Monarchs 6 Chapter 3: Homestead Grays 15 Chapter 4: Birmingham Black Barons 24 Chapter 5: Integration 29 Chapter 6: Conclusion 37 Appendix I: Players that played both Negro and Major Leagues 41 Appendix II: Timeline for Integration 45 Bibliography: 47 2 Chapter 1: Introduction From the late 19th century until 1947, Major League Baseball (MLB, the Majors, the Show or the Big Show) was segregated. During those years, African Americans played in the Negro Leagues and were not allowed to play in either the MLB or the minor league affiliates of the Major League teams (the Minor Leagues). The Negro Leagues existed as a separate entity from the Major Leagues and though structured similarly to MLB, the leagues were not equal. The objective of my thesis is to cover how and why MLB integrated and the impact of MLB’s racial integration on three prominent Negro League teams. The thesis will begin with a review of the three Negro League teams that produced the most future Major Leaguers. I will review the rise of those teams to the top of the Negro Leagues and then the decline of each team after its superstar(s) moved over to the Major Leagues when MLB integrated. -

Pakistan Fears Nabs 6 Indian Strike

VOL. 67 NO. 309, TWIN FALLS, IDAHO, THURSpAY APRIL 8,'1971 CENTS - w r WASHINGTON (U PI) -Pres leave Vietnam by Dec. 1, “The issue very simply is ident Nixon, deplaring his goal cutting Ann^Tican troop this: Shall we leave Vietnam in m "total.. wnnffl'flwfii ~ ! fs5 r strengtn to 'IBPO ir But he a way that —by our own Vietnam,” pledged Wednesday rejected demands of his critics ‘actions —consciously turns the ” night to accelerate the Ameri that he set a definite date for country over to the Commu- can troop pull-out, removing" an end to American involVe- nists? Or shall we leave in a 100,000 men fironi the war zone ment-in- the-warj-saying-he— way- That gives the... South duiteg a seven-month period intended'to ehd tl^e conflict “in Vietnamese a ' reasonable starting May .l. a way that will redeem the chance to survive as_a_free In a 20ininute ■ televised sacrifices that have been people?” address, Nixon said the addi made” by U.S. forces in more “Nfy.plan will end American tional U.S. servicemen would than 10 years,of fighting. involvement in a way that would provide .that, chance,” Nixon said. “Tlie other would end it precipitately and give victory to the Communists.” Nixon said his program of Vietnamization —atrengthening South Vietnamese forces to assume the burden of fighting X. I— the-<^ar —“has succecfdeJr” -Ameriean-forcSs-in-Vietnam -Vt- will be reduced to 284,000 by May 1. The rate of withdrawal sinc^ puUouts started July 8. 1969, has averaged 12,500 men a month. -

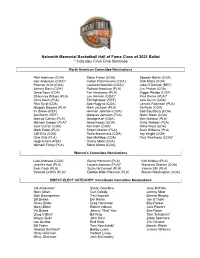

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

CONTENTS CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Media Information

CONTENTS CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Media Information ............................................. Inside Front Quick Facts, UNA Team Photo ........................................... 2 Lion Basketball Tradition ................................................. 4-5 2008-09 2008-09 Basketball Schedule ............................................. 3 Head Coach Bobby Champagne .................................... 6-8 Assistant Coaches ............................................................... 9 Season Preview ................................................................. 10 Alphabetical and Numerical Rosters ................................ 11 CREDITS 2008-09 Player Profiles ................................................ 12-21 The 2008-09 University of North Alabama men’s basketball media guide was compiled and edited by sports information 2007-08 REVIEW director Jeff Hodges and assistant SID Shane Herrmann. 2007-08 Scores ................................................................. 22 Player photos and the cover photo by UNA photographer 2007-08 Statistics ............................................................. 23 Shannon Wells. Cover design is by UNA publications assistant Karen Hodges. LION RECORDS AND HISTORY Individual Records ............................................................ 24 AWARDS The University of North Alabama men’s basketball media Team Records ................................................................... 25 guide has been judged among the “Best in the Nation,” in Season-by-Season Leaders -

November 22, 1977 Solutions Offered for Parking Problem

MADISON MEMORIAL L'.3.7ARY Jomec Madison University- e cB&eze Harrioriurg, VA 22301 Tuesday November 22, 1*77 No. 23 Vol. LV James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia Commuters urge X lot division By MARK DAVISON A proposal allocating 199 spaces in X parking lot for commuter use was presented to the Parking Advisory Committee Nov. 15 by the Commuter Student Com- mittee Chairman. The proposal was based on the findings of a commuter student task force which studied the X lot parking patterns during a two-week period in October and November. After studying the findings of their survey, the commuter committee came to a "compromise" proposal, which they felt to be fair to both residents and com- muters, according to Wayne Baker, commuter committee chairman and a member of RESIDENT STUDENTS occupy the front spaces in X lot at approximately 11 p.m. Sunday night the parking committee. Photo by Mark Tbompaon The commuters propose Faculty praise, criticize: that "the first three fanes in X lot and the 21 spaces in the small lot just south of the main X lot, as well as the 13 Formation of new school questioned spaces along the road through X lot be designated for By THERESA BEALE state of the university's move—up to the ad- penses coming out of setting 'Commuter Use Only.'" Dividing the School of Arts development. ministration and Board of up an additional dean's office Also, the dommuter and Sciences into the College In an informal survey of Visitors." for the school. committee requested that of Letters and Sciences and faculty members, some said President Ronald Carrier The university is "already "the road behind the N- the School of Fine Arts and splitting the School of Arts and said he could not comment on overloaded, top heavy with complex dorms and the Communication has brought Sciences would direct more Funston's remarks because administrative officers," spaces along the road to the words of praise from attention to the departments the new school has been in the according to a biology tunnel under 1-81 should be re- department heads. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Bulletin 11/00

NORTH CAROLINA HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION BULLETIN VOL. 53, NO. 2 WINTER 2000-01 Four Named To Join Association Hall of Fame CHAPEL HILL—Four more outstanding names in the annals of ’85 and were runners-up in ’82. HisPage teams went to the playoffs state prep athletics have been selected for induction into the North 16 times and won 13 league crowns. In all, 25 of his teams won at Carolina High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame. least seven games, and his career coaching mark at the prep level Marion Kirby of Greensboro, Don Patrick of Newton, Hilda was 278-65-8. Worthington of Greenville and the late Charles England of Lexington A member of the Lenoir-Rhyne College Sports Hall of Fame, have been chosen as the 14th group of inductees to join the presti- Kirby left Page to build Greensboro College’s new football program gious hall. That brings to 62 the number enshrined. from scratch. The Pride fielded its first team in 1997. The new inductees were honored during special halftime cere- He also was a tireless worker for the North Carolina Coaches monies at a football game at Kenan Stadium this fall when North Association as secretary-treasurer for many years after participating Carolina played on Georgia Tech. The University of North Carolina in the East-West football game as a player in 1960. designated the day as the 16th annual NCHSAA Day. They will offi- Don R. Patrick cially inducted at the special Hall of Fame banquet next spring at the A native of Shelby, Don Patrick has built a tremendous record as Friday Center in Chapel Hill. -

Sports Official Sports

FOR THE UP AND COMING AND ALREADY ARRIVED $3 • ISSUE 33 • JUNE 2011 vbFRONT.com The Impact of Recreational Fuzzy Minnix, Sports Official Sports WELCOME to the FRONT When it comes to sports, there’s opportunity on all sides. You don’t have to be a “jock” to see it. That’s the message in this edition’s cover story. Although we talked to 16 individuals and looked into 14 organizations, we only wish we could have brought you the good news from many, many more sources. These are passionate people. Positive people. The story is one of re-creation of a community—through recreation. And with regions all across the country looking for a sporting chance at recovery and rebound, it’s good to hear we’re making that happen right here—on our own playing fields. Tom Field Dan Smith ”take a look at a piece of bylined “ reporting written by a journalist who also blogs. The differences between the two should be clear. — Page 30 Walk in. See Jimmie. If anyone knows floors, it’s Jimmie! • Carpet and Area Rugs • Hardwood, Cork and Bamboo • Resilient • Tile • Laminate Sales, Installation and Service. Jimmie Blanchard, owner 385 Radford St • Christiansburg, VA 24073 • 540-381-1010 • www.FLOOREDLLC.com vbFRONT / JUNE 2011 u 3 CONTENTS Valley Business FRONT COVER STORY DEPARTMENTS 8 TRENDS etiquette & protocol 18 workplace advice 19 business dress 20 FINANCIAL FRONT 22 LEGAL FRONT 25 WELLNESS FRONT 28 TECH/INDUSTRY FRONT 30 DEVELOPMENT FRONT 34 Inprint. Page 38 RETAIL FRONT 40 Instyle. SENIOR FRONT 42 EDUCATION FRONT 44 CULTURE FRONT 46 REVIEWS & OPINIONS dan smith 48 tom field 49 letters 51 Commercial Real Estate book reviews 52 Report Card Page 34 FRONT’N ABOUT 54 ECONOMIC INDICATORS 57 EXECUTIVE PROFILE 60 FRONTLINES career front 62 front notes 66 Bike Shop Dude Page 40 vbFRONT.com Cover photography of Fuzzy Minnix by morefront.blogspot.com Greg Vaughn Photography. -

Men's Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall Series Began 1912-13

Men’s Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall series began 1912-13 Beckleheimer NOTE Beckleheimer was a three sport letterwinner at Morris Harvey College. Possibly the first in school history. 1913-14 5-3 Wesley Alderman ROSTER C. Fulton, Taylor, B. Fulton, Jack Latterner, Beckelheimer, Bolden, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Marshall, (19-42). NOTE According to the 1914 Yearbook: “Latterner best basketball man in the state” PHOTO Team photo: 1914 Yearbook, pg. 107 flickr.com UC sports archives 1917-18 8-2 Herman Beckleheimer ROSTER Golden Land, Walter Walker HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Swept Marshall 1918-19 ROSTER Watson Haws, Rollin Withrow, Golden Land, Walter Walker 1919-20 11-10 W.W. Lovell ROSTER Watson Haws 188 points Golden Land Hollis Westfall Harvey Fife Rollin Withrow Jones, Cano, Hansford, Lambert, Lantz, Thompson, Bivins NOTE Played first full college schedule. (Previous to this season, opponents were a mix from colleges, high schools and independent teams.) 1920-21 8-4 E.M. “Brownie” Fulton ROSTER Land, Watson Haws, Lantz, Arthur Rezzonico, Hollis Westfall, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Won two out of three vs. Marshall, (25-21, 33-16, 21-29) 1921-22 5-9 Beckleheimer ROSTER Watson Haws, Lantz, Coon, Fife, Plymale, Hollis Westfall, Shannon, Sayre, Delaney HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Virginia Tech, (22-34) PHOTO Team photo: The Lamp, May 1972, pg. 7 Watson Haws: The Lamp, May 1972, front cover 1922-23 4-11 Beckleheimer ROSTER H.C. Lantz, Westfall, Rezzonico, Leman, Hager, Delaney, Chard, Jones, Green. PHOTO Team photo: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 107 Individual photos: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 109 1923-24 ROSTER Lantz, Rezzonico, Hager, King, Chard, Chapman NOTE West Virginia Conference first year, Morris Harvey College one of three charter members. -

Police Guard Is Ordered for Council Session 5% Surtax

The Daily Register VOL 97 NO. 136 SHREWSBURY, N. J. MONDAY, DECEMBER 30, 1974 TEN CENTS Police guard is ordered for council session By JANE FODERARO yesterday that the governing body had ordered police protec- people stormed the podium'1 And why weren't arrests made ihe citys KcvplMce »i ihe original revaluation m (act at tion at tonight's meeting, but refused to comment on the num- immediately'1" She is expected to appear ai tonight's meeting apparent discrepant irs citnl in Hie n poll LONG BRANCH - Police will stand guard at tonights ber of officers requested to denounce the arrests — The CCG, which ha- bent promoting i change in the City Council meeting when several political groups are ex- "Ask them; they ordered it." he said (The emotionally charged meeting »( Dec 10 Incused on pected to zero in on.a variety of controversial issues here, not torn of government here, ;IIMI li expected lo raise • new is- The council members who could be reached refused to the fatal shooting of an unarmed black youth by a city police- sue They are In dew,mil inswwi fnm\ city official! regard' the least of which is the council's latest effort to insure order comment. However, it was learned that at least four officers man A state Grand Jury today was to continue hearing evi- at City Council meetings ing fees charged lui rammer M ;i beacn facility funded will stand guard in the meeting hall while reinforcements will dence in the incident, including testimony from local police ) through the open Spacei Land Program "(the federal Hous- The council on Friday ordered police guards to avoid a re- be on call in another part of City Hall — Two politically active organizations Citizens for Com- ing and I'rban Development (III11)) agenc) According lo peat of a melee that broke out at the Dec. -

Nba Legacy -- Dana Spread

2019-202018-19 • HISTORY NBA LEGACY -- DANA SPREAD 144 2019-20 • HISTORY THIS IS CAROLINA BASKETBALL 145 2019-20 • HISTORY NBA PIPELINE --- DANA SPREAD 146 2019-20 • HISTORY TAR HEELS IN THE NBA DRAFT 147 2019-20 • HISTORY BARNES 148 2019-20 • HISTORY BRADLEY 149 2019-20 • HISTORY BULLOCK 150 2019-20 • HISTORY VC 151 2019-20 • HISTORY ED DAVIS 152 2019-20 • HISTORY ellington 153 2019-20 • HISTORY FELTON 154 2019-20 • HISTORY DG 155 2019-20 • HISTORY henson (hicks?) 156 2019-20 • HISTORY JJACKSON 157 2019-20 • HISTORY CAM JOHNSON 158 2019-20 • HISTORY NASSIR 159 2019-20 • HISTORY THEO 160 2019-20 • HISTORY COBY WHITE 161 2019-20 • HISTORY MARVIN WILLIAMS 162 2019-20 • HISTORY ALL-TIME PRO ROSTER TAR HEELS WITH NBA CHAMPIONSHIP RINGS Name Affiliation Season Team Billy Cunningham (1) Player 1966-67 Philadelphia 76ers Charles Scott (1) Player 1975-76 Boston Celtics Mitch Kupchak Player 1977-78 Washington Bullets Tommy LaGarde (1) Player 1978-79 Seattle SuperSonics Mitch Kupchak Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bobby Jones (1) Player 1982-83 Philadelphia 76ers Mitch Kupchak (3) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo (2) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1986-87 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy (3) Player 1987-88 Los Angeles Lakers Michael Jordan Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player