Mary Mcleod Bethune Papers: the Bethune-Cookman College Collection, 1922–1955

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

Everything Man Paul Robeson the Form and Function Of

EVERYTHING THE MAN FORM AND FUNCTION PAUL OF ROBESON SHANA L. REDMOND EVERYTHING MAN refiguring american music A series edited by Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, and Nina Sun Eidsheim Charles McGovern, contributing editor duke university press | durham and london | 2020 EVERYTHING MAN THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF PAUL ROBESON shana l. redmond © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk Text designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Whitman by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Redmond, Shana L., author. Title: Everything man : the form and function of Paul Robeson / Shana L. Redmond. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019015468 (print) lccn 2019980198 (ebook) isbn 9781478005940 (hardcover) isbn 9781478006619 (paperback) isbn 9781478007296 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976. | Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976—Criticism and interpretation. | Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976—Political activity. | African American singers— Biography. | African American actors—Biography. Classification: lcc e185.97.r63 r436 2020 (print) | lcc e185.97.r63 (ebook) | ddc 782.0092 [b]—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015468 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980198 Cover art: Norman Lewis (1909–1979), Too Much Aspiration, 1947. Gouache, ink, graphite, and metallic paint on paper, 21¾ × 30 inches, signed. © Estate of Norman Lewis. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery llc, New York, NY. This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to tome (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)— a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and the ucla Library. -

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro Spirituals for Solo Vocalist Compiled by Randye Jones This is a sample of recordings recommended for enhancing library collections of Spirituals and, thus, is limited (with one exception) to recordings available on compact disc. This list includes a variety of voice types, time periods, interpretative styles, and accompaniment. Selections were compiled from The Spirituals Database, a resource referencing more than 450 recordings of Negro Spiritual art songs. Marian Anderson, Contralto He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands (1994) RCA Victor 09026-61960-2 CD, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, Hamilton Forrest, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, Roland Hayes Spirituals (1999) RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-63306-2 CD, recorded between 1936 and 1952, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, John C. Payne, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, Hamilton Forrest, Robert MacGimsey, Roland Hayes, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, R. Nathaniel Dett Angela Brown, Soprano Mosiac: a collection of African-American spirituals with piano and guitar (2004) Albany Records TROY721 CD, variously with piano, guitar Songs by Angela Brown, Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Betty Jackson King, Roland Hayes, Joseph Joubert Todd Duncan, Baritone Negro Spirituals (1952) Allegro ALG3022 LP, with piano Songs by J. Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, William C. Hellman, Edward Boatner Denyce Graves, Mezzo-soprano Angels Watching Over Me (1997) NPR Classics CD 0006 CD, variously with piano, chorus, a cappella Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Marvin Mills, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Shelton Becton, Roland Hayes, Robert MacGimsey Roland Hayes, Tenor Favorite Spirituals (1995) Vanguard Classics OVC 6022 CD, with piano Songs by Roland Hayes Barbara Hendricks, Soprano Give Me Jesus (1998) EMI Classics 7243 5 56788 2 9 CD, variously with chorus, a cappella Songs by Moses Hogan, Roland Hayes, Edward Boatner, Harry T. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

2014 AAAM Conference Booklet

2014 Annual Conference Association of African American Museums HELP US BUILD THE MUSEUM h i P s A n e r s n d C r t o l P A l A B o r A t i o n s Birmingham, Alabama i August 6–9, 2014 n t RENEW your membership today. h e BECOME a member. DONATE. d The National Museum of African American History and i Culture will be a place where exhibitions and public g hosted by i programs inspire and educate generations to come. t Birmingham Civil rights institute A l Visit nmaahc.si.edu for more information. A g Program Design: Chris Danemayer, Proun Design, LLC. e Back Cover Front Cover THINGS HAVE CHANGED. SO HAVE WE. Association AAAM HISTORICAL OVERVIEW of African American Museums The African American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s Board of Directors, 2013–2014 and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the Black experience and to ensure its Officers proper interpretation in American history. Black museums instilled a sense At the place of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Samuel W. Black of achievement within Black communities, while encouraging collaborations death in 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, the President National Civil Rights Museum was born. Pennsylvania between Black communities and the broader public. Most importantly, the African American Museums Movement inspired new contributions to society and Dr. Deborah L. Mack The Museum, a renowned educational Vice President advanced cultural awareness. Washington, D.C. and cultural institution that chronicles the In the late 1960s, Dr. Margaret Burroughs, founder of the DuSable Museum American Civil Rights Movement, has been Auntaneshia Staveloz Secretary in Chicago, and Dr. -

Executive Director Selected for Amistad Research Center

Tulane University Executive director selected for Amistad Research Center June 04, 2015 9:00 AM Alicia Duplessis Jasmin [email protected] Kara Tucina Olidge replaces Lee Hampton, who retired in June 2014, as head of the Amistad Research Center on the uptown campus of Tulane University. (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano) In her new position as executive director of the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, Kara Tucina Olidge has outlined several goals for her first few years of tenure. The most ambitious of these goals is to double the center's endowment over a three- to five-year period. “This will allow us to focus on staff development and collections development,” says Olidge, who holds a doctorate in educational leadership and policy from State University of New York-Buffalo. “You have to think big, and you have to hit the ground running.” The center's current endowment is $2.25 million, and Olidge plans to use her previous experience in corporate development, grant writing and strategic planning to hit the $4.5 million goal by 2020. "We were impressed with how engaged she'd been with the community in previous positions. We're confident she'll do the same at Amistad." Tulane University | New Orleans | 504-865-5210 | [email protected] Tulane University Sybil Morial, board member, Amistad Research Center This experience is what made Olidge the standout candidate, says Sybil Morial, a 30-year Amistad board member and chair of the executive director search committee. “She knew about fiscal management and fund development,” says Morial of Olidge. “We were also impressed with how engaged she'd been with the community in previous positions. -

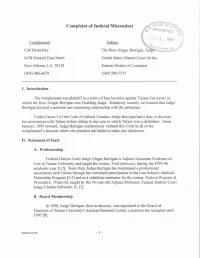

Complaint of Judicial Misconduct

Complaint of Judicial Misconduct Complainant arl Bernofsky The Hon. Ginger Berrigan. Ju 6478 General Diaz treet United tates District Court for the New Orleans LA 70124 Eastern District of Louisiana (504) 486-46"9 (504) 589-7515 I. Introduction The complainant was plaintiff in a serie of four lawsuits against Tulane Universit in which th Hon. Ginger Berrigan was Pr siding Judge. Relatively recent) , he learned that Judge Berrigan has had a material and continuing relationship with the defendant. Under Canon 3 of the ode of Judicial onduct, Judge Berrigan had a duty to disclose her as ociation with Tulane before sitting in any cas in which Tulane was a defendant. From Januar , 1995 onward Judge Berrigan continuously violated this Code in all of the complainant's lawsuits where she presided and failed to make any disclo ure. II. Statement of Facts A. Professorship Federal District ourt Judge Ginger Berrigan i Adjunct Associate Professor of Law at Tulane University and taught the cours Trial Advocacy during the 1995-96 academic year [1 2]. Since then, Judge Berrigan has maintained a professional association with Tulane through her continued participation in the Law School's Judicial Externship Program [3-5] and as a substitute instructor for the course, Federal Practice & Procedure: Trials [6], taught by the 76-year-old Adjunct Professor Federal District Court Judge Charles Schwartz Jr. [7]. B. Board Membership In 1990, Judge Berrigan then an attorney was appointed to the Board of Directors of Tulane University's Amistad Research Center, a position she occupied until 1997 [8]. 13 ERRIGAN.Q9C - I - The Amistad Research Center occupies a wing of Tilton Memorial Hall on the campus of Tulane University [9]. -

Folklorist of the Brush and Palette: Rare Winold Reiss Exhibition

“Folklorist of the Brush and Palette”: Rare Winold Reiss Exhibition Features Distinct, Illuminating Portraits of Harlem Figures by Victoria L. Valentine on May 3, 2018 • 8:58 am WINOLD REISS, “Harlem Girl with Blanket,” circa 1925 FORTY WORKS BY A HARLEM LEGEND are on view in midtown Manhattan. “Winold Reiss Will Not Be Classified” at Hirschl & Adler gallery presents works spanning the German American artist’s four decade career. Winold Reiss (1886–1953) was variously considered an artist, designer, illustrator, architect, printmaker, and muralist. The exhibition, the first compre- hensive presentation of Reiss’s work in three decades, features oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, prints and drawings that capture a range of subjects, including a handful of works about Harlem. Reiss famously made portraits of W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson, Charles S. Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, and Alain Locke. Nearly a century ago, Locke edited a special issue of Survey Graphic dedicated to black artistic expression. The March 1925 edition of the social science journal was full of essays by writers and intellectuals such as Du Bois, Albert C. Barnes, Arthur Schomburg, who were shaping the cultural discourse, and selec- tions by young African American poets, including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Anne Spencer, and Jean Toomer, who would come to define the Harlem Renaissance. The seminal publication was both a literary and visual record. Titled “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” the issue was illustrated by Reiss, who contributed stylized portraits of Harlem figures, Art Deco graphics, and a cover portrait of Roland Hayes, the composer and tenor vocalist regarded as the first internationally recognized African American concert performer. -

ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS at the HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964)

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 25-43 Orth 25 ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS AT THE HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964) Nikki Orth The Pennsylvania State University Abstract: Ella Baker’s 1964 address in Hattiesburg reflected her approach to activism. In this speech, Baker emphasized that acquiring rights was not enough. Instead, she asserted that a comprehensive and lived experience of freedom was the ultimate goal. This essay examines how Baker broadened the very idea of “freedom” and how this expansive notion of freedom, alongside a more democratic approach to organizing, were necessary conditions for lasting social change that encompassed all humankind.1 Key Words: Ella Baker, civil rights movement, Mississippi, freedom, identity, rhetoric The storm clouds above Hattiesburg on January 21, 1964 presaged the social turbulence that was to follow the next day. During a mass meeting held on the eve of Freedom Day, an event staged to encourage African-Americans to vote, Ella Baker gave a speech reminding those in attendance of what was at stake on the following day: freedom itself. Although registering local African Americans was the goal of the event, Baker emphasized that voting rights were just part of the larger struggle against racial discrimination. Concentrating on voting rights or integration was not enough; instead, Baker sought a more sweeping social and political transformation. She was dedicated to fostering an activist identity among her listeners and aimed to inspire others to embrace the cause of freedom as an essential element of their identity and character. Baker’s approach to promoting civil rights activism represents a unique and instructive perspective on the rhetoric of that movement. -

Print ED381426.TIF (18 Pages)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 426 SO 024 676 AUTHOR Barnett, Elizabeth F. TITLE Mary McLeod Bethune: Feminist, Educator, and Social Activist. Draft. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Educational Research Association (New Orleans, LA, April 4-9, 1994). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blacks; *Black Studies; Civil Rights; Cultural Pluralism; *Culture; *Diversity (Institutional); Females; *Feminism; Higher Education; *Multicultural Education; Secondary Education; *Women' Studies IDENTIFIERS *Bethune (Mary McLeod) ABSTRACT Multicultural education in the 1990s goes beyond the histories of particular ethnic and cultural groups to examine the context of oppression itself. The historical foundations of this modern conception of multicultural education are exemplified in the lives of African American women, whose stories are largely untold. Aspects of current theory and practice in curriculum transformation and multicultural education have roots in the activities of African American women. This paper discusses the life and contributions of Mary McLeod Bethune as an example of the interconnections among feminism, education, and social activism in early 20th century American life. (Author/EH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made frt. the original doci'ment. ***************************A.****************************************** MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE: FEMINIST, EDUCATOR, AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST OS. 01411111111111T OP IMILICATION Pico of EdwoOomd Ill000s sod Idoomoome EDUCATIOOKL. RESOURCES ortaevAATION CENTEO WW1 Itfto docamm was MOO 4144116414 C111fteico O OM sown et ogimmio 0940411 4 OWV, Chanin him WWI IWO le MUM* 41014T Paris of lomat olomomosiedsito dew do rot 110011441104, .611.1181184 MON OEM 001140 01040/ Elizabeth F.