Scripture As Literature: Michael Austin's Job

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holy Trinity & St. Michael

Kewaskum Catholic Parishes of Holy Trinity & St. Michael Staff Holy Trinity & St. Michael Shared Pastor www.kewaskumcatholicparishes.org Rev. Jacob A. Strand Holy Trinity Office –Ext. 104 Deacon: Rev. Mr. Ralph Horner St. Michael Office – 262-334-5270 Cell Phone – 262-343-1795 [email protected] Hours: Wednesdays 6:30pm—8pm Holy Trinity Church 305 Main Street P.O. Box 461 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-626-2860 Fax – 262-626-2301 Dir. of Admin Services– Mrs. Nancy Boden Ext. 106 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Ext. 105 [email protected] St. Michael Church 8883 Forest View Road Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-334-5270 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Holy Trinity School 305 Main Street P.O. Box 464 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone 262-626-2603 Website: www.htschool.net Principal – Mrs. Amanda Longden Ext. 101 [email protected] School Secretary—Mrs. Angela Schickert Ext. 100—[email protected] Faith Formation Program Phone 262-626-2650 WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE DAILY MASS SCHEDULE Dir. of Faith Formation/Coordinator for K—8th Grade—Mrs. Mary Breuer Saturday 4:00 p.m.—St. Michael Tuesdays 5:00 p.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] Sunday 7:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Wednesdays 6:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Associate Director/Coordinator for H.S. Sunday 9:00 a.m.—St. Michael Thursdays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity Youth Ministry—Mrs. Jessica Herriges Sunday 11:00 a.m.—Holy Trinity Fridays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION EUCHARSTIC ADORATION Joint Pastoral Council Chair Mrs. -

President's Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families

President’s Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families, Happy Feast of Sts. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels! Yesterday we celebrated our patronal feast and the 3rd anniversary of the dedication of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Chapel. As our fourth year is now underway, we can look back and celebrate the many accomplishments of SMA in the past and look forward to our exciting future together, confident that our patron, St. Michael, will defend us in the battle. Whenever I visit the doctor, there are four words I never like to hear: “Now this may hurt.” That message brings about two responses in me, the first is one of dread… it means I’m going to be experiencing something I really don’t want! Secondly, I brace in anticipation of what is about to happen; I’m able to make myself ready for the event. September is the month of Our Lady of Sorrows (in Latin, the seven “dolors”). When Mary encountered Simeon in the temple, she heard the same message in a more intense form, “this is going to hurt.” The prophet told her, A sword will pierce through your own soul. Mary, a new mother still in wonder at the miraculous birth of her child, now hears that her life is going to be integrally tied to his sufferings. So September is always a month linked to compassion; the compassion Mary had for her son and has for us. It is also a reminder of the compassion we can have for each other. -

St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY

SEPTEMBER Activity 6 St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY Age level: All ages Recommended time: 10 minutes What you need: St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book), SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel (optional), colored pencils and/or markers, and scissors Activity A. Explain to your students that we have been learning that the Devil and his fallen angels tempt us to sin. We can pray a special, very powerful prayer to St. Michael to help us combat these evil spirits. St. Michael is not a saint, but an archangel. The archangels are leaders of the other angels. According to both Scripture and Catholic Tradition, St. Michael is the leader of the army of God. He is often shown in paintings and iconography in a scene from the book of Revelation, where he and his angels battle the dragon. He is the patron of soldiers, policemen, and doctors. B. Have your students turn to St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book) and pray together the prayer to St. Michael the Archangel. You may wish to play a sung version of the prayer, which you can find at SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel. C. Finally, have your students color in the St. Michael shield and attach it to their prayer boards. © SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us St. Michael the Archangel protects us against danger and the Devil. He is our defense and our shield and the Church has given us a special prayer so that we can ask him for help. -

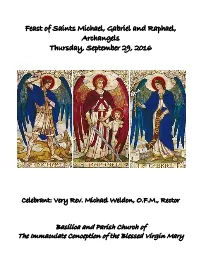

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016 Celebrant: Very Rev. Michael Weldon, O.F.M., Rector Basilica and Parish Church of The Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary The Angelus V. The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary: R. And she conceived by the Holy Spirit. Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. V. Behold the handmaid of the Lord: R. Be it done unto me according to thy word. Hail Mary... V. And the word was made flesh: R. And dwelt among us. Hail Mary... V. Pray for us, O Holy Mother of God. R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ. Pour forth, we beseech thee, O Lord, thy grace into our hearts, that we to whom the incarnation of Christ Thy Son was made known by the message of an angel, may by His Passion and Cross be brought to the glory of His resurrection; through the same Christ our Lord. Amen. Entrance Chant Michael, Prince of All the Angels Michael, prince of all the angels, Gabriel, messenger to Mary, While your legions fill the sky, Raphael, healer, friend and guide, All victorious over Satan, All you hosts of guardian angels Lift your flaming sword on high; Ever standing by our side, Shout to all the seas and heavens: Virtues, Thrones and Dominations, Now the morning is begun; Raise on high your joyful hymn, Now is rescued from the dragon Principalities and Powers, She whose garment is the sun! Cherubim and Seraphim! Mighty champion of the woman, Mighty servant of her Lord, Come with all your myriad warriors, Come and save us with your sword; Enemies of God surround us: Share with us your burning love; Let the incense of our worship Rise before His throne above! Gloria Gospel Acclamation Sanctus Mystery of Faith Amen Agnus Dei Prayer to St. -

May 20Th, 2021

May 20th, 2021 Pentecost and Paulist Ordination The feast of Pentecost is this Sunday, May 23rd. As the Holy Spirit breathes new life into the hearts of the faithful, we're excited to celebrate with a little more togetherness! Pentecost is a yearly reminder to share Christ's light, and gives us an opportunity to consider how we can bring God's ministry into the world. This spirit of ministry provides us with the perfect backdrop to welcome two new priests into the Paulist Fathers! The staff of St. Paul's has also been focused on ministry this week. With the world ever so slowly opening back up, St. Paul's looks forward to seeing you! Keep an eye out for events as we rebuild the ministries that make up our vibrant and thriving community. Join us in celebrating the priestly ordination of Deacon Michael Cruickshank, CSP, and Deacon Richard Whitney, CSP, this Saturday, May 22nd at 11AM at St. Paul the Apostle Church! Bishop Richard G. Henning will be the principal celebrant. The public is welcome to attend the mass! In addition, it will be broadcast live at paulist.org/ordination as well as on the Paulist Fathers’ Facebook page and YouTube channel. If you can't attend the ceremony, our two new Paulist Fathers will be saying their First Masses at the 10AM and 5PM masses on Sunday, May 23rd. However you're able to participate, we hope you will join us in celebrating these men as they journey into God's ministry! Ordination 2021 A Note from Pastor Rick Walsh This weekend we celebrate the presbyteral ordination of two Paulists, Michael Cruickshank and Richard Whitney. -

The Chaplet of St. Michael

The Chaplet of St. Michael O God, come to my assistance. O Lord, make haste to help me. Glory be to the Father, etc. 1. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Seraphim may the Lord make us worthy to burn with the fire of perfect charity. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 2. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Cherubim may the Lord grant us the grace to leave the ways of sin and run in the paths of Christian perfection. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 3. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Thrones may the Lord infuse into our hearts a true and sincere spirit of humility. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 4. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Dominations may the Lord give us grace to govern our senses and overcome any unruly passions. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 5. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Virtues may the Lord preserve us from evil and falling into temptation. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 6. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Powers may the Lord protect our souls against the snares and temptations of the devil. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 7. By the intercession of St. Michael and the celestial Choir of Principalities may God fill our souls with a true spirit of obedience. Amen. Our Father and three Hail Marys 8. -

3 Sunday of Ordinary Time January 24-25. 2015 Fr. Michael Renninger “Oh Jonah He Lived in a Whale. Oh Jonah He Lived in a Whal

3rd Sunday of Ordinary Time January 24-25. 2015 Fr. Michael Renninger “Oh Jonah he lived in a whale. Oh Jonah he lived in a whale. He made his home in that fish’s abdomen. O Jonah he lived in a whale.” That song is from George Gershwin’s great opera, Porgy and Bess. Sadly, when most Christians hear the name “Jonah,” the only thing they know is what Gershwin wrote in his song. They know that Jonah got swallowed by a big fish. When it comes to the prophet Jonah, that’s about all we know. Fortunately, we get to hear a bit more about Jonah in today’s first reading. And, what we learn about Jonah may surprise us. In the Book of the Prophet Jonah, Jonah was called by God to preach a message of repentance. God called Jonah, and said to him, “Go to the great city of Nineveh, and tell them to repent. If you do, I will forgive their sins.” Nineveh was an enormously large city. And it was an enormously sinful city (I think it was in Nineveh that they first learned how to deflate footballs!). It was a city of excessive sin. Perhaps Nineveh was like Las Vegas and New Orleans at Mardi Gras, all rolled into one. In other words -lots of sin! Oh, and there was one other problem. Nineveh was an enemy of Israel, and the people who lived in Nineveh were not part of the Chosen People. They were foreigners. And they were sinners. That is where Jonah’s problem begins. -

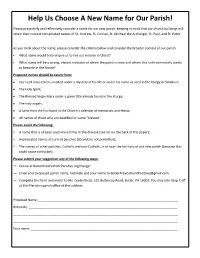

Help Us Choose a New Name for Our Parish!

Help Us Choose A New Name for Our Parish! Please prayerfully and reflectively consider a name for our new parish, keeping in mind that our church buildings will retain their current consecrated names of St. Andrew, St. Conrad, St. Michael the Archangel, St. Paul, and St. Peter. As you think about the name, please consider the criteria below and consider the broader context of our parish: What name would truly inspire us to live our mission in Christ? What name will be a strong, vibrant indicator of whom the parish is now and whom this faith community wants to become in the future? Proposed names should be taken from: Our Lord Jesus Christ, invoked under a mystery of his life or under his name as used in the liturgy or Scripture; The Holy Spirit; The Blessed Virgin Mary under a given title already found in the liturgy; The holy angels; A saint from the list found in the Church’s calendar of memorials and feasts; All names of those who are beatified or name “blessed”. Please avoid the following: A name that is already used many times in the diocese (see list on the back of this paper); Hyphenated names of current parishes (absolutely not permitted); The names of other parishes, Catholic and non-Catholic, in or near the territory of our new parish (because that could cause confusion). Please submit your suggestion any of the following ways: Online at ButlerAreaCatholicParishes.org/merger Email your proposed parish name, rationale and your name to [email protected] Complete this form and mail it to Ms. -

Meet the Liverpool High School Class of 2021

Liverpool High School Top of the Class Saivamsi Jake Nataly Peter Jonah Adabala Appler Avotins Bachman Balthazor Stony Brook SUNY Le Moyne Penn State University University Geneseo College University at Buffalo Kendall Claudia Michaela Mackenzie Shannon Blincoe Brown Burt Cahl Carey Syracuse University SUNY Mercyhurst Le Moyne University of Tampa Oneonta University College Sydney Azaria Dominique Sara Jacob Carlson Chapman Walker Cimini Connell Crawford Stony Brook Binghamton Le Moyne University SUNY University University College at Buffalo Plattsburgh 4 Liverpool Central School District Liverpool High School Top of the Class Brandon Joshua Gina Alyssa Destiny Davis DeJoy Dellavella DiMillo Dowdell University Binghamton Le Moyne Alfred Howard of Connecticut University College University University Amanda Mia Delaney Jackson Robert Dwyer Forde Gellert Gellert Golden Binghamton Rochester Institute Drexel Hobart and William Stony Brook University of Technology University Smith Colleges University Samuel Theo Ian Juliana Jenna Gross Gross Hallenbeck Heneka Irwin Alfred Alfred Kansas State Binghamton Robert Morris University University University University University School Bell (Graduation 2021) 5 Celebrating the Class of 2021 The next four pages list, in alphabetical order, the candidates for graduation from Liverpool High School’s Class of 2021. The photos on pages 1, 2, 7 and 8 are this year’s Liverpool High School Top of the Class. The students are listed in alphabetical order with the names of the colleges or universities they plan to -

Saint Matthias Parish to Live out the Message of Jesus Christ and Become, in Fact and 409 Hemenway St

Mission Statement Saint Matthias Parish To live out the message of Jesus Christ and become, in fact and 409 Hemenway St. appearance, a true Christian community. Marlborough, MA 01752 Faith Formation Faith formation is a lifelong process: an ongoing interaction with Phone: 508-460-9255 God’s creative goodness. We allow the Gospel to transform us Fax: 508-480-8801 and then bring transformation to the world. The Faith Formation Program at St. Matthias Parish provides opportunities to grow as individuals and as a community. We offer classroom sessions for children, a comprehensive Confirmation program, intergenerational learning in a variety of formats, and an adult enrichment program. For more information, contact Theresa Salafia ([email protected]). Community Prayer Line Our prayer line, coordinated by Marie Mangan (978-562-2891), offers prayers for you, your loved ones and friends. Requests may also be placed in the "Prayer Request" box at the rear of the Church. All requests will be kept confidential. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults Those who are not baptized or have been baptized into another Christian community and are interested in learning more about Parish Leadership initiation into the Catholic faith are invited to speak with Theresa Francis P. O'Brien, Pastor Salafia ([email protected]). [email protected] Doug Peltak, Deacon Infant Baptism [email protected] Our parish celebrates the sacrament of Baptism for infants and children under the age of 7 at regularly scheduled Sunday Paul G. Coletti, Deacon Masses. Please call Deacon Doug at any time during pregnancy [email protected] or at least two months in advance for information on baptismal Theresa Salafia, Faith Formation Director catechesis and the choosing of godparents. -

'Philomena' Story Spurs Catholic Alums' Effort to Help Mom Know Her

‘Philomena’ story spurs Catholic alums’ effort to help mom know her son By Penny Wiegert Catholic News Service ROCKFORD, Ill. – Several Boylan Central Catholic High School alums are seeking “to help a mom know her son.” After all, Boylan is more than a community. Lynn Perez-Hewitt (class of 1971) says it’s smaller than that. “It really is a tight connection, a family,” she said. And families stick together. Families help each other. In this case, the “mom” they are reaching out to is the woman upon whom the Oscar- nominated movie “Philomena” is based. The “son” is Michael Hess, Boylan class of 1970. The idea to reach out to Philomena Lee was hatched long before any of Hess’ former classmates ever heard about a movie. Their goal had everything to do with fond memories of Mike as a good, faithful and talented friend. About a year ago Lynn Cuppini McConville, Boylan’s director of advancement, was asked if she knew about the book “The Lost Child of Philomena Lee” by BBC correspondent Martin Sixsmith. It was brought to her attention by Boylan staff member Ingrid Jansen. Jansen’s sister-in-law lives in Ireland, happened to read the book, and was surprised to see Rockford mentioned. McConville said she checked it out and couldn’t believe that the lost son mentioned in the book was Hess, a fellow classmate and friend who she remembers as being “such a nice and intense young man.” She said she was hesitant at first because the story highlights harsh attitudes and an unattractive chapter in church history. -

A Stuller Ring Story: Michael, Jacob, and Michael

A Stuller Ring Story: Michael, Jacob, and Michael Continuing our celebration of Stuller’s Year of the Wedding™, we are highlighting stunning engagement rings and the Stuller associates who wear them. There is something special about a custom designed engagement ring. Infusing personal touches into a ring —an inscription, design detail, or birthstone — creates a piece that is truly one-of-a-kind and something that comes from the heart. Three members of our Product Design & Development CAD team gave special attention and care to creating their wives’ rings. Filled with significance and unique features you’d expect from designers, these rings symbolize their lasting love. These are Michael, Jacob, and Michael’s ring stories. Michael Bartlett For CAD design manager Michael Bartlett, his wife Alexis is the strongest person he knows. Both originally from New Orleans, they met in 2006 in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Over the course of their relationship, Michael feels they grew together through incredibly significant times in their lives that helped them know and understand each other. He wanted the ring he made for Alexis to reflect that journey. His goal for the ring was to make something she would never have to take off. A teacher at the time and active with her hands, he wanted Alexis to be able to wear the ring everywhere and not have to worry about it. The ring he created was a 14K white gold split shank bypass with a faux tension-set center. This securely holds the natural diamond center and ensures the ring doesn’t get caught during everyday use.