Own House and Dalit: Selected Villages in Karnataka State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Content Page No's 1-5 6 6 7 8 9 10-12 13-50 51-52 53-82 83-93

Table of Content Executive summary Page No’s i. Introduction 1-5 ii. Background 6 iii. Vision 6 iv. Objective 7 V. Strategy /approach 8 VI. Rationale/ Justification Statement 9 Chapter-I: General Information of the District 1.1 District Profile 10-12 1.2 Demography 13-50 1.3 Biomass and Livestock 51-52 1.4 Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography 53-82 1.5 Soil Profile 83-93 1.6 Soil Erosion and Runoff Status 94 1.7 Land Use Pattern 95-139 Chapter II: District Water Profile: 2.1 Area Wise, Crop Wise irrigation Status 140-150 2.2 Production and Productivity of Major Crops 151-158 2.3 Irrigation based classification: gross irrigated area, net irrigated area, area under protective 159-160 irrigation, un irrigated or totally rain fed area Chapter III: Water Availability: 3.1: Status of Water Availability 161-163 3.2: Status of Ground Water Availability 164-169 3.3: Status of Command Area 170-194 3.4: Existing Type of Irrigation 195-198 Chapter IV: Water Requirement /Demand 4.1: Domestic Water Demand 199-200 4.2: Crop Water Demand 201-210 4.3: Livestock Water Demand 211-212 4.4: Industrial Water Demand 213-215 4.5: Water Demand for Power Generation 216 4.6: Total Water Demand of the District for Various sectors 217-218 4.7: Water Budget 219-220 Chapter V: Strategic Action Plan for Irrigation in District under PMKSY 221-338 List of Tables Table 1.1: District Profile Table 1.2: Demography Table 1.3: Biomass and Live stocks Table 1.4: Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography Table 1.5: Soil Profile Table 1.7: Land Use Pattern Table -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

No. HCE 535/2013 HIGH COURT of KARNATAKA BENGALURU, DATED: 19.12.2016

No. HCE 535/2013 HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA BENGALURU, DATED: 19.12.2016. INTERVIEW INTIMATION LETTER The interview to the remaining eligible candidates as per annexure, for recruitment to the post of Peon(Cooks) on the Establishment of High Court of Karnataka, as called for vide Notification No. HCE 535/2013 dated 18.11.2014, is Scheduled to be held from 9th January, 2017 to 21st January, 2017, in the premises of the Hon’ble High Court of Karnataka, Bengaluru. Further, the call letters for the interview to the said 297 eligible candidates are already dispatched through speed post. The candidates as stated in the annexure are informed to be present for the interview well in time on the date shown in the list alongwith the following original certificates/documents at the time of interview:- 1. Marks Card of Tenth Standard or Equivalent and character certificates/ID proof. 2. The original experience letter for having worked as cook. 3. If you are claiming the benefit of reservation/age relaxation under Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe/Cat- I/IIA/IIB/IIIA/IIIB, the Certificate in the form prescribed by the Government issued by the Competent Authority, in proof of your claim. 4. If you are claiming reservation under Local Cadre i.e., belonging to Hyderabad Karnataka Region, the relevant certificate issued by the Competent Authority as prescribed under the Karnataka Public Employment (Reservation in appointment for Hyderabad Karnataka Region) (Issue of Eligibility Certificate) Rules, 2013. If the original documents relied upon by the candidates are not produced at the time of interview they are liable to be disqualified. -

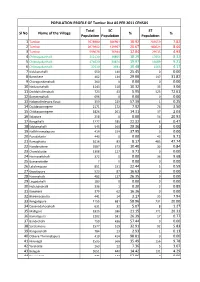

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Tumkur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Tumkur 2678980 506901 18.92 209559 7.82 2 Tumkur 2079902 429957 20.67 180024 8.66 3 Tumkur 599078 76944 12.84 29535 4.93 4 Chiknayakanhalli 212130 38805 18.29 17654 8.32 5 Chiknayakanhalli 174620 34874 19.97 16089 9.21 6 Chiknayakanhalli 37510 3931 10.48 1565 4.17 7 Kidukanahalli 550 140 25.45 0 0.00 8 Bannikere 462 134 29.00 147 31.82 9 Choragondanahalli 260 0 0.00 0 0.00 10 Naduvanahalli 1143 118 10.32 35 3.06 11 Doddahullenahalli 723 43 5.95 525 72.61 12 Bommenahalli 696 0 0.00 0 0.00 13 Halumalledevara Kaval 399 229 57.39 1 0.25 14 Doddayannegere 2171 172 7.92 76 3.50 15 Chikkayannegere 1824 261 14.31 37 2.03 16 Salapura 258 0 0.00 54 20.93 17 Baragihalli 1277 285 22.32 6 0.47 18 Sabbenahalli 545 160 29.36 0 0.00 19 Hallithimmalapura 419 159 37.95 0 0.00 20 Puradakatte 443 0 0.00 43 9.71 21 Ramaghatta 1016 83 8.17 485 47.74 22 Handanakere 3587 373 10.40 30 0.84 23 Chowlakatte 1308 127 9.71 0 0.00 24 Honnasettihalli 372 0 0.00 36 9.68 25 Bumanakatte 7 0 0.00 0 0.00 26 Lakshmipura 851 191 22.44 5 0.59 27 Gopalapura 523 87 16.63 0 0.00 28 Harenahalli 482 127 26.35 0 0.00 29 Lingadahalli 183 0 0.00 0 0.00 30 Hutchanahalli 336 1 0.30 3 0.89 31 Kanakere 379 62 16.36 0 0.00 32 Bheemasandra 441 14 3.17 35 7.94 33 Kengalapura 1155 681 58.96 231 20.00 34 Davanadahosahalli 631 32 5.07 8 1.27 35 Malligere 1825 386 21.15 371 20.33 36 Kamalapura 2202 581 26.39 17 0.77 37 Bandrehalli 759 436 57.44 0 0.00 38 Soralamavu -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 ANANTAPUR Anantapur ANANTAPUR SBMY0040929 ANANTAPUR SBMY004092899497

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 18/251 OLD Town GURUPRASA D COMPLEX RF ROAD ANANTAPUR – 515001 ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR Anantapur PRADESH ANANTAPUR SBMY0040929 D NO 25- 619/1 LAKSHMI CHENNAKES AV PURAM ANDHRA DHARMAVAR CHARMAVAR DHARMAVAR PRADESH ANANTAPUR AM AM 515671 AM SBMY00409289949791122 16-2-3 Gandhi ANDHRA Chowk Main PRADESH ANANTAPUR Hindupur Bazar-515201 HINDUPUR SBMY004000508556-220860 2-930 POSTAL COLONY KONGA REDDY PALLI ANDHRA CHITTOR PRADESH CHITTOOR CHITTOR 517001 CHITTOOR SBMY00409279494742863 ANDHRA KUPPAM - PRADESH CHITTOOR Kuppam 517 425 A.P. KUPPAM SBMY004000408579-55039 ANDHRA MADANAPAL MADANAPAL PRADESH CHITTOOR Madanapalle LE - 517 325 LE SBMY004000208571-262017 CAR STREET ANDHRA PUNGANURU PRADESH CHITTOOR Punganuru - 517 247 PUNGANUR SBMY004000308581-53040 564/C IST D Balaji Colony ANDHRA Thirupathi- PRADESH CHITTOOR Tirupati 517501 TIRUPATI SBMY00403750877-2260754 21-50/1 Hospital Complex ANDHRA EAST Bahanugudi PRADESH GODAVARI Kakinada centre KAKINADA SBMY00405310884-2378769 Main Rd Jetty RAJAHMUND Complex D RY, No.8-24-154 ANDHRA EAST RAJAHMUND Rajahmundry- RAJAHMUND ph.0883- PRADESH GODAVARI RY 533101 RY SBMY00404552498703 5/1 Arundalpet ANDHRA IV Lane PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur -522002 GUNTUR SBMY00403010863-2233092 3-29-218/a Bhavya Castle Krishna Nagar Main Road Opp. ESI Hospital ANDHRA Lakshmipura Guntur PRADESH GUNTUR m (Guntur) 522007 GUNTUR SBMY0040949 4-14978 ANDHRA ABIDS ROAD PH.040- PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD HYDERABAD SBMY004029323387712 (03592)- 221808,221809, -

Remarks Afzalpur Page 1 of 55 04/04/2019

List of Cancellation of Polling Duty S. No. Letter No. Name Designation Department Emp. ID S/W/DO Reason for cancellation Office Class remarks Rehearsal Centre Code: 1 Assembly Segment under which centre falls Afzalpur 139750 AMARNATH DHULE ASSISTANT ENGINEER PW-PUBLIC WORKS 1 17004700020002 DEPARTMENT Cancelled by Committee Marriage PRO KUPENDRA DHULE Office of the Executive Engineer, PWP & IWTD ,Division Old Jewargi 143801 SIDRAMAPPA B WALIKAR SERICULTURE INSPECTOR SE-COMMISSIONER FOR 2 17005900020012 SERICULTURE DEVELOPMENT SST TEAM IN AFZALPUR PRO BHIMASYA WALIKAR DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF SERICULTURE 144462 DR SHAKERA TANVEER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR EC-DEPARTMENT OF 3 17001400080012 COLLEGIATE EDUCATION DOUBLE ORDERS PRO MOHAMMED JAMEEL AHMED Government First Grade College Afzalpur 144467 DR MALLIKARJUN M SAVARKAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR EC-DEPARTMENT OF 4 17001400090005 COLLEGIATE EDUCATION EVM NODAL OFFICER IN PRO MADARAPPA AFZALPUR Govt First Grade Colloge Karajagi Tq Afzalpur Dist Gulbarga 144476 NAVYA N LECTURER ET-DEPARTMENT OF 5 17001800010067 TECHNICAL EDUCATION ON MATERNITY LEAVE PRO NARASIMHAREDDY B LECTURER SELECTION GRADE 144569 JALEEL KHAN JUNIOR ENGINEER MR-DEPARTMENT OF MINOR 6 17003800020022 IRRIGATION SECTOR OFFICER IN AFZALPUR PRO OSMAN KHAN Assistant Executive Engineer 144813 HUMERA THASEEN TRAINED GRADUATE TEACHER QE-3201QE0001-BEO AFZALPUR 7 17008300090006 (TGT) Cancelled by Committee UMRAH PRO M A RASHEED TOUR. BLOCK EDUCATIONAL OFFICER AFZALPUR 145726 SHARANABASAPPA DRAWING MASTER QE-DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC 8 17004900540008 -

Language Handbook, Tumkur

MYSORE CENSUS 1951 LANGUAGE HANDBOOK TUMKUR DISTRICT J. B. MALLARAU>HY A Published for the Government of India by the Manager of Publications and Printed at the Government Press, Bangalore by the Director of Printing in Myson~ 19~~ TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY LANGUAGE PATTERN OF TUMKUR DISTRICT III STATEMENT SHOWING DIFl!'ERENCES BETWEEN THE ORIGINAL AND PRESENT SORTINGS IV TABLES Madhugiri Taluk 1 Koratagere Taluk 9 Sira Taluk 15 Pavagada Taluk 21 FACING PAGE LANGUAGE MAPS Tumkur District III Madhugiri Taluk 1 Koratagere Taluk ,9 Sira Taluk 15 Pavagada Taluk 21 INtRODUCTORY Towards the end of August 1953, the Government of Mysore asked me to undertake tbe extmction of figures relating to Scheduled Castes and S,0heduled Tribes, for submission of circle wise statements to the Delimitation Commission. Just when the work was about to be taken on hand accordingly, the Prime Minister happened to announce in Parliament that a High Power Commission was shortly to be appointed to go into the question of reorganisation of States. Since this meant that sooner or later there would be a demand for village wise language data, at least in respect of bilingual areas· in the State, I sought the permission of the Deputy Regis trar General to extract the language figures simultaneously with the extraction of figures for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. rrhe Deputy Registrar Genera.!, India, readily fell in with my view but suggested that the extraction of villagewise language data, be confined only to taluks lying' on either side of a lingui8tic dividing line.' Accordingly, figures ,\'ere extracted for the villages of the following 13 clearly bilingual taluks :-- BANGALOltE DISTRICT TUMKUR DISTRICT KOLAIt DIS~RIC~' CHITALDRUG DIS'rRW'l' Hoskote Pavagada MaIm Challakere Devanhalli Koratagere Kolllr Anekal Madhugiri Goribidnur DodballapUI' Chikballapur Sidlllghatta With villagewise language data cmnpiled for the above taluks, I thought I had anticipated all pos8ible demands. -

Tumkur University 2017-18

TUMKURTUMKUR UNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY TUMKUR UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 EXTRACT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE ACADEMIC COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 27.10.2018 SUB NO: 2018-19: 3ꃇ ಸಾ.풿.ಪ:01:ಸಾ.ಅ:04,颿ನಕ:27.10.2018 Approval of University Annual Report 2017-18 DECISION: Academic Council has approved the draft Annual Report for the year 2017-18 and recommended to submit it to the approval of the Syndicate and to the Government at the earliest. EXTRACT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYNDICATE MEETING HELD ON 29.10.2018 SUB NO: 2018-19: 4ꃇ ಸಾ.ಸ: 04: ಸಾ/ಅ:01, 颿ನಕ:29.10.2018 Approval of University Annual Report 2017-18 DECISION: The Syndicate has approved the draft Annual Report for the year 2017-18 which was approved by the Academic Council. The Syndicate recommended submitting the report to the Government at the earliest. CONTENTS Sl. No Particulars Page No. 1 Statutory Authorities of University : 1 2 Statutory Officers : 1 3 Human Resource Development Section : 10 4 Academic Section : 16 5 General and Development Section : 28 6 Finance Section : 36 7 Examination Section : 51 8 Engineering Section : 68 9 University Library : 72 10 Physical Education and Sports : 83 11 National Service Scheme : 86 12 Prasaranga : 89 DEPARTMENTS OF STUDIES AND RESEARCH 13 Dr. D. V. Gundappa Kannada Adhyana Kendra : 90 14 Department of Studies and Research in English : 101 15 Department of Studies and Research in History and Archaeology : 108 16 Department of Studies and Research in Economics : 115 17 Department of Studies and Research in Political Science : 132 18 Department -

District Census Handbook, Tumkur, Part XII-B, Series-11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 Series - 11 KARNATAKA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TUMKUR DISTRICT PART XII- B VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT SOBHA NAMBISAN Director of Census Operations, Karnataka CONTENTS Page No. FOREWORD v-vi PREFACE vii-viii IMPORTANT STATISTICS ix-xii ANALYTICAL NOTE 1-30 Explanatory Note 33-36 A.District Primary Census Abstract 38-56 (i) Villagerrown Primary Census Abstract Alphabetical List of Villages - ChiknayakanhaUi C.D.Block 61-66 Primary Census Abstract - ChiknayakanhaHi C.D.Block 68-95 Alphabetical List of Villages - Gubbi CO.Block 99-107 Primary Census Abstract - Gubbi C.D.Block 108-151 Alphabetical List of Villages - Koratagere CD.Block 155-160 Primary Census Abstract - Koratagere CD.Block 162-193 Alphabetical List of Villages - Kunigal C.D.Block 19:7-204 Primary Census Abstract - Kunigal C.D.Block 206-245 Alphabetical List of Villages - Madhugiri CD.Block 249-256 Primary Census Abstract - Madhugiri CD.Block 258-297 Alphabetical List of Villages - Pavagada C.D.Block 301-304 Primary Census Abstract - Pavagada C.D.Block 306-325 Alphabetical List of Vil1ages - Sira CD.Block 329-334 Primary Census Abstract - Sira C.D.Block 336-367 Alphabetical List of Villages - Tiptur C.D.Block 371-376 Primary Census Abstract - Tiptur CO.Block 378-405 Alphabetical List of Villages - Tumkur CD.Block 409-417 Primary Census Abstract - Tumkur C.D.Block 418-465 Alphabetical List of Villages - Turuvekere C.D.Block 469-474 Primary Census Abstract - Turuvekere C.D.Block 476-507 (iii) Page 1\[0. (ii) Town Primary Census Abstract (Wardwise) Alphabetical List of Towns 511 Adityapatna (NMCT) 512-515 Chiknayakanhalli (TMe) 512-515 Gubbi (MP) 512-515 Koratagcrc (MP) 512-515 KUfi\gat (TMC) 516-519 Madhugiri (TMC) 516-519 Pavagada (MP) 516-519 Sira (TMC) 516-519 Tiptur (TMC) 516-519 Turuvckere (M?) 516-519 Y.N.Hosakote (MP) 520-523 Tumkur (UA) 520-523 B. -

Gulbarga District Provisional Primary Mutual

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION - KARNATAKA PROVISIONAL LIST OF TEACHERS ELIGIBLE FOR MUTUAL TRANSFER - 2013 ( PRIMARY WITHIN UNIT ) TRANSFER AUTHORITY : DDPI GULBARGA APPLICATION NO KGID NO APPLICATION NO KGID NO APLLICANT NAME APLLICANT NAME DESIGNATION SUBJECT DESIGNATION SUBJECT DOB : DOJS DISE SCHOOL CODE DOB : DOJS DISE SCHOOL CODE SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL NAME VILLAGE NAME / AREA NAME VILLAGE NAME / AREA NAME TALUK NAME DISTRICT NAME TALUK NAME DISTRICT NAME Sl.No. FIRST TEACHER / APPLICANT SECOND TEACHER / APPLICANT 1 020996 1779513 020996 474602 VASANT BANDAPPA PULAR RAMCHANDRA Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL ( HM ) ( HM ) 15/09/1963 : 01/06/1985 29040111101 01/08/1954 : 03/11/1978 29040102801 GOVT HPS SAVALESHWAR GOVT HPS DANNUR SAWALESHWAR DHANNUR ALAND GULBARGA ALAND GULBARGA BEO REMARKS ACCEPTED BEO REMARKS ACCEPTED 2 053087 1222812 053087 1227021 VENKATLAXMI MADIVALAPPA Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL ( HM ) ( HM ) 01/06/1971 : 03/07/1990 29040901201 01/06/1962 : 28/09/1984 29040901901 GOVT HPS BHUTAPUR GOVT HPS CHITAKANPALLI BHUTAPUR CHITAKANAPALLI SEDAM GULBARGA SEDAM GULBARGA BEO REMARKS ACCEPTED BEO REMARKS ACCEPTED 3 059364 791656 059364 726241 RAMCHANDRA H PAWAR NIRMALA TENGLI Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL Head Master / Head Mistress KANNADA - GENERAL ( HM ) ( HM ) 04/02/1964 : 01/06/1985 29041103002 23/07/1956 : 28/02/1978 29041102701 GOVT HPS KAGGANAMADI GOVT HPS JAMAGA [B] KAGGANMADRI -

Gram Panchayat Human Development

Gram Panchayat Human Development Index Ranking in the State - Districtwise Rank Rank Rank Standard Rank in in Health in Education in District Taluk Gram Panchayat of Living HDI the the Index the Index the Index State State State State Bagalkot Badami Kotikal 0.1537 2186 0.7905 5744 0.7164 1148 0.4432 2829 Bagalkot Badami Jalihal 0.1381 2807 1.0000 1 0.6287 4042 0.4428 2844 Bagalkot Badami Cholachagud 0.1216 3539 1.0000 1 0.6636 2995 0.4322 3211 Bagalkot Badami Nandikeshwar 0.1186 3666 0.9255 4748 0.7163 1149 0.4284 3319 Bagalkot Badami Hangaragi 0.1036 4270 1.0000 1 0.7058 1500 0.4182 3659 Bagalkot Badami Mangalore 0.1057 4181 1.0000 1 0.6851 2265 0.4169 3700 Bagalkot Badami Hebbali 0.1031 4284 1.0000 1 0.6985 1757 0.4160 3727 Bagalkot Badami Sulikeri 0.1049 4208 1.0000 1 0.6835 2319 0.4155 3740 Bagalkot Badami Belur 0.1335 3011 0.8722 5365 0.5940 4742 0.4105 3875 Bagalkot Badami Kittali 0.0967 4541 1.0000 1 0.6652 2938 0.4007 4141 Bagalkot Badami Kataraki 0.1054 4194 1.0000 1 0.6054 4549 0.3996 4163 Bagalkot Badami Khanapur S.K. 0.1120 3946 0.9255 4748 0.6112 4436 0.3986 4187 Bagalkot Badami Kaknur 0.1156 3787 0.8359 5608 0.6550 3309 0.3985 4191 Bagalkot Badami Neelgund 0.0936 4682 1.0000 1 0.6740 2644 0.3981 4196 Bagalkot Badami Parvati 0.1151 3813 1.0000 1 0.5368 5375 0.3953 4269 Bagalkot Badami Narasapura 0.0902 4801 1.0000 1 0.6836 2313 0.3950 4276 Bagalkot Badami Fakirbhudihal 0.0922 4725 1.0000 1 0.6673 2874 0.3948 4281 Bagalkot Badami Kainakatti 0.1024 4312 0.9758 2796 0.6097 4464 0.3935 4315 Bagalkot Badami Haldur 0.0911 4762