Structuring Licenses to Avoid the Inadvertent Franchise by Rochelle Spandorf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slavery in America: the Montgomery Slave Trade

Slavery In America The Montgomery Trade Slave 1 2 In 2013, with support from the Black Heritage Council, the Equal Justice Initiative erected three markers in downtown Montgomery documenting the city’s prominent role in the 19th century Domestic Slave Trade. The Montgomery Trade Slave Slavery In America 4 CONTENTS The Montgomery Trade Slave 6 Slavery In America INTRODUCTION SLAVERY IN AMERICA 8 Inventing Racial Inferiority: How American Slavery Was Different 12 Religion and Slavery 14 The Lives and Fears of America’s Enslaved People 15 The Domestic Slave Trade in America 23 The Economics of Enslavement 24–25 MONTGOMERY SLAVE TRADE 31 Montgomery’s Particularly Brutal Slave Trading Practices 38 Kidnapping and Enslavement of Free African Americans 39 Separation of Families 40 Separated by Slavery: The Trauma of Losing Family 42–43 Exploitative Local Slave Trading Practices 44 “To Be Sold At Auction” 44–45 Sexual Exploitation of Enslaved People 46 Resistance through Revolt, Escape, and Survival 48–49 5 THE POST SLAVERY EXPERIENCE 50 The Abolitionist Movement 52–53 After Slavery: Post-Emancipation in Alabama 55 1901 Alabama Constitution 57 Reconstruction and Beyond in Montgomery 60 Post-War Throughout the South: Racism Through Politics and Violence 64 A NATIONAL LEGACY: 67 OUR COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF SLAVERY, WAR, AND RACE Reviving the Confederacy in Alabama and Beyond 70 CONCLUSION 76 Notes 80 Acknowledgments 87 6 INTRODUCTION Beginning in the sixteenth century, millions of African people The Montgomery Trade Slave were kidnapped, enslaved, and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas under horrific conditions that frequently resulted in starvation and death. -

Introduction to the Captured German Records at the National Archives

THE KNOW YOUR RECORDS PROGRAM consists of free events with up-to-date information about our holdings. Events offer opportunities for you to learn about the National Archives’ records through ongoing lectures, monthly genealogy programs, and the annual genealogy fair. Additional resources include online reference reports for genealogical research, and the newsletter Researcher News. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is the nation's record keeper. Of all the documents and materials created in the course of business conducted by the United States Federal government, only 1%–3% are determined permanently valuable. Those valuable records are preserved and are available to you, whether you want to see if they contain clues about your family’s history, need to prove a veteran’s military service, or are researching an historical topic that interests you. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records December 14, 2016 Rachael Salyer Rachael Salyer, archivist, discusses records from Record Group 242, the National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, and offers strategies for starting your historical or genealogical research using the Captured German Records. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records Rachael is currently an archivist in the Textual Processing unit at the National Archives in College Park, MD. In addition, she assists the Reference unit respond to inquiries about World War II and Captured German records. Her career with us started in the Textual Research Room. Before coming to the National Archives, Rachael worked primarily as a professor of German at Clark University in Worcester, MA and a professor of English at American International College in Springfield, MA. -

Vazquez V. Jan-Pro Franchising Int'l

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT GERARDO VAZQUEZ, GLORIA No. 17-16096 ROMAN, and JUAN AGUILAR, on behalf of themselves and all other D.C. No. similarly situated, 3:16-cv-05961- Plaintiffs-Appellants, WHA v. OPINION JAN-PRO FRANCHISING INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendant-Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of California William Alsup, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 18, 2018 San Francisco, California Filed May 2, 2019 Before: Ronald M. Gould and Marsha S. Berzon, Circuit Judges, and Frederic Block, District Judge.* Opinion by Judge Block * The Honorable Frederic Block, United States District Judge for the Eastern District of New York, sitting by designation. 2 VAZQUEZ V. JAN-PRO FRANCHISING INT’L SUMMARY** California State Law / Employment Law The panel vacated the district court’s dismissal on summary judgment of a complaint brought by a putative class against a defendant international business that had developed a sophisticated “three-tier” franchising model, seeking a determination whether workers were independent contractors or employees under California wage order laws; and remanded for further proceedings. In a decision post-dating the district court’s decision, the California Supreme Court in Dynamex Ops. W. Inc. v. Superior Court, 416 P.3d 1 (Cal. 2018), adopted the “ABC test” for determining whether workers are employees under California wage order laws. The test requires the hiring entity to establish three elements to disprove employment status: (A) that the worker is free from the control of the hiring entity in connection with work performance – both under the performance contract and in fact; (B) that the worker performs work outside the hiring entity’s usual business; and (C) that the worker is customarily engaged in an independent business of the same nature as the work performed. -

Dragnet 55-02-08 286 the Big Gap.Pdf

,A 1 J + . -Y icy + AV A A Iff N X i • 4 .A h ' DATE MMSTERFIELD 1 118 NBC q#286 R . EA SE . .. .FEBRUARY 8, 1955 DIRECTOR. , . .JACK WEBB SPONSOR . CHESTERFIELD CIGARETTES PER . .FRANK,BURT AGENCY. CUNNINGHAM-WALSH IC . .-., . .WALTER SCHUMAN N SQRIPT . JEAN MILES BOUND . BUD . TO=, SON ' & _ WAVNF' KFNWQRTrW _ENGINEER . RAOUL MURPHY LG 0190220 BIG GAP SGT . JOE FRIDAY . .JACK WEBS OFF9 FRANK SMITH . .BEN ALEXANDER FRED ALPIN. .JACK KRUSCHEN SARAH HUNT. .VIRGINIA GREGG GARFIELD HUNT. .VIC RODMAN PETE (DBL.) . JAKE - BARTENDER . .HERB ELLIS PEG. GEORGIA ELLIS CLEAVER (SUSPECT) . .HARRY BARTEILL WILCOXSON (DBL .) . ., . LG 0190221 DRAGNET RADIO 273/55 OPENING 1 ANNCR : Chesterfield brings you Dragnet . 2 MUSIC : HARP UP AND OU T 3 GIRL : Put a smile in your smoking ! 4 ANNCR : Buy Chesterfield . So smooth . so satisfying . , 5 Chesterfie LG 0190222 -1- NNSIC : HARP UP AND OUT : Put a smile in your smoking . ►1GIRL ENN : Next time you buy cigarettes - Stop. Remember this In--the whole wide world, no cigar tte satisfies lik e Che s to rf ie` ti r-.,,,,,,~ SIC : DRAGNET THEME $1 UNDER ' ANNCR : Ladies . Gentlemen . The storyyou are about to hear is due . The names have been changed to protect th e innocent . rR ROLL 10 WgB-:--~-Dragnet,- brought- bo-.-you - by Chesterfield . -- 11 MUSIC : UP AND FADE FOR 12 FENN : (EASILY) You're a detective sergeant . You're assigned 13 to Bunco-Fugitive Detail . A Pawnbroker tells you he 14 suspects a swindle . He isn't sure . Your job . .checlk 15 it ou x i 16 MUsic : UP AND FADE FOR 17 (FIRST COMMERCIAL INSERT) LG 0190223 A I FIRST COMMERCIA L MUSIC : HN UP AND OUT 3 GIRL: Put a smile in your smoking ! 4 FENN: Next time you buy cigarettes . -

Extensions of Remarks

April 26, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 8535 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS BENEFITS OF AUTOMATION First-class mail delivery performance was "The mail is not coming in here so we ELUDE POSTAL SERVICE at a five-year low last year, and complaints have to slow down," to avoid looking idle, about late mail rose last summer by 35 per said C. J. Roux, a postal clerk. "We don't cent, despite a sluggish 1 percent growth in want to work ourselves out of a job." HON. NEWT GINGRICH mall volume. The transfer infuriated some longtime OF GEORGIA Automation was to be the service's hope employees, who had thought that they IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for a turnaround. But efforts to automate would be protected in desirable jobs because have been plagued by poor management and of their seniority. Thursday, April 26, 1990 planning, costly changes of direction, inter "They shuffled me away like an old piece Mr. GINGRICH. Mr. Speaker, as we look at nal scandal and an inability to achieve the of furniture," said Alvin Coulon, a 27-year the Postal Service's proposals to raise rates paramount goal of moving the mall with veteran of the post office and one of those and cut services, I would encourage my col fewer people. transferred to the midnight shift in New Or With 822 new sorting machines like the leans. "No body knew nothing" about the leagues to read the attached article from the one in New Orleans installed across the Washington Post on the problems of innova change. "Nobody can do nothing about it," country in the last two years, the post of he said. -

EPA SLN No. MS-090005

EPA SLN No. MS-090005 EPA Reg. No. 279-3062 FOR DISTRIBUTION For use to supplement application of preconstruction Bora-Care AND USE ONLY WITHIN primary treatments THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI 24(c) Supplemental Label DIRECTIONS FOR USE It is a violation of Federal law to use this product in a manner inconsistent with its labeling. This label must be in the possession of the user at the time of pesticide application. Follow all applicable directions, restrictions, Worker Protection Standard requirements, and precautions on the EPA registered label. This 24(c) label is only approved for use in conjunction with a pre-construction Bora-Care primary treatment. This label is not intended to authorize stand-alone use for the Exterior Perimeter / Interior Spot labeling in the State of Mississippi. When a pre-construction Bora-Care primary treatment is used for control of subterranean termites and is applied according to label directions for use, DRAGNET SFR insecticide must be applied as an exterior perimeter pre-construction treatment using a 0.5%, 1% or 2% dilution after final grade is established. DRAGNET SFR insecticide must be applied to provide a continuous treated zone around the entire exterior foundation wall of the building. It is required that a complete and continuous treated zone be achieved around the entire exterior perimeter, including under any attached slabs such as garages, porches, patios, driveways, and pavement adjoining the foundation. DRAGNET SFR insecticide may also be applied to critical areas that include plumbing and utility penetrations (including bath traps), shower drain penetrations, along settlement cracks and expansion joints, and dirt filled porches. -

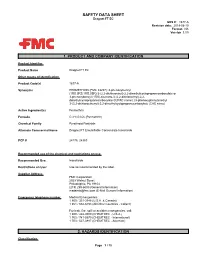

Dragnet FT EC SDS # : 1677-A Revision Date: 2019-08-15 Format: NA Version 1.09

SAFETY DATA SHEET Dragnet FT EC SDS # : 1677-A Revision date: 2019-08-15 Format: NA Version 1.09 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Identifier Product Name Dragnet FT EC Other means of identification Product Code(s) 1677-A Synonyms PERMETHRIN (FMC 33297): 3-phenoxybenzyl (1RS,3RS;1RS,3SR)-3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylate or 3-phenoxybenzyl (1RS)-cis-trans-3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2- dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylate (IUPAC name); (3-phenoxyphenyl)methyl 3-(2,2-dichloroethenyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylate (CAS name) Active Ingredient(s) Permethrin Formula C21H20Cl2O3 (Permethrin) Chemical Family Pyrethroid Pesticide Alternate Commercial Name Dragnet FT Emulsifiable Concentrate Insecticide PCP # 24175, 24360 Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use Recommended Use: Insecticide Restrictions on Use: Use as recommended by the label. Supplier Address FMC Corporation 2929 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 (215) 299-6000 (General Information) [email protected] (E-Mail General Information) Emergency telephone number Medical Emergencies : 1 800 / 331-3148 (U.S.A. & Canada) 1 651 / 632-6793 (All Other Countries - Collect) For leak, fire, spill or accident emergencies, call: 1 800 / 424-9300 (CHEMTREC - U.S.A.) 1 703 / 741-5970 (CHEMTREC - International) 1 703 / 527-3887 (CHEMTREC - Alternate) 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Classification Page 1 / 10 Dragnet FT EC SDS # : 1677-A Revision date: 2019-08-15 Version 1.09 OSHA Regulatory Status This material is considered hazardous by the OSHA Hazard -

17-1299 Franchise Tax Bd. of Cal. V. Hyatt (05/13/2019)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2018 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus FRANCHISE TAX BOARD OF CALIFORNIA v. HYATT CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF NEVADA No. 17–1299. Argued January 9, 2019—Decided May 13, 2019 Respondent Hyatt sued petitioner Franchise Tax Board of California (Board) in Nevada state court for alleged torts committed during a tax audit. The Nevada Supreme Court rejected the Board’s argument that the Full Faith and Credit Clause required Nevada courts to ap- ply California law and immunize the Board from liability. The court held instead that general principles of comity entitled the Board only to the same immunity that Nevada law afforded Nevada agencies. This Court affirmed, holding that the Full Faith and Credit Clause did not prohibit Nevada from applying its own immunity law. On remand, the Nevada Supreme Court declined to apply a cap on tort liability applicable to Nevada state agencies. This Court reversed, holding that the Full Faith and Credit Clause required Nevada courts to grant the Board the same immunity that Nevada agencies enjoy. The Court was equally divided, however, on whether to over- rule Nevada v. Hall, 440 U. -

Highway Patrol Dragnet Saved by the Bell (E/I) the Waltons the Flintstones Have Gun, Will Travel the Jetsons (Eff. 2/21) The

Daniel Boone EFFECTIVE 2/21/21 ALL TIMES EASTERN / PACIFIC MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00a Dragnet The Beverly Hillbillies 6:00a The Powers of Matthew Star 6:30a My Three Sons The Beverly Hillbillies 6:30a 7:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:00a Toon In With Me Popeye and Pals 7:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 7:30a 8:00a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:00a The Tom and Jerry Show 8:30a Leave It to Beaver Saved by the Bell (E/I) 8:30a 9:00a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:00a Perry Mason Bugs Bunny and Friends 9:30a Saved by the Bell (E/I) 9:30a 10:00a The Flintstones 10:00a Matlock Maverick 10:30a The Flintstones 10:30a 11:00a The Flintstones 11:00a In the Heat of the Night Wagon Train 11:30a The Jetsons (Eff. 2/21) 11:30a 12:00p 12:00p The Waltons The Big Valley 12:30p 12:30p The Brady Bunch Brunch 1:00p 1:00p Gunsmoke Gunsmoke 1:30p 1:30p 2:00p 2:00p Bonanza Bonanza 2:30p 2:30p 3:00p The Rifleman 3:00p Rawhide Gilligan's Island Three Hour Tour 3:30p The Rifleman 3:30p 4:00p Have Gun, Will Travel 4:00p Wagon Train 4:30p Wanted: Dead or Alive 4:30p 5:00p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:00p 5:30p Adam-12 The Rifleman Mama's Family 5:30p 6:00p The Flintstones 6:00p The Love Boat 6:30p Happy Days 6:30p The Three Stooges 7:00p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:00p 7:30p M*A*S*H M*A*S*H 7:30p 8:00p The Andy Griffith Show 8:00p 8:30p The Andy Griffith Show Svengoolie 8:30p Columbo 9:00p Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. -

Structuring Licenses to Avoid the Inadvertent Franchise

Structuring Licenses To Avoid The Inadvertent Franchise by Rochelle B. Spandorf Trademark Licensors Beware: Is Your License or Distribution Agreement Really a Franchise? In Gentis v. Safeguard Business Systems,1 the defendant retained commissioned sales agents to solicit orders, follow leads, and provide customer service. The agents did more than just take orders, but lacked authority to enter into binding sales contracts with customers, never took title any goods, never bought inventory, seldom made deliveries, and did not handle billing or collection. When the relationship between the agents and Safeguard soured, the agents sued Safeguard for violating California s Franchise Investment Act, the first franchise sales law in the country and the model for both the federal and state franchise sales laws that followed.2 In one of the few California appellate court decisions interpreting the statute, to Safeguard s surprise, the court found that the relationship between the sales agents and Safeguard to be a franchise. In Charts v. Nationwide Insurance Co.,3 a Connecticut federal district court found an insurance agency to be a franchise within the scope of the Connecticut Franchise Act and concluded that Nationwide had wrongfully terminated the agency without good cause in violation of the Connecticut statute justifying a $2.3 Million judgment award. While the judgment was eventually reversed three years later on different grounds,4 it temporarily rocked an industry that had never seriously considered the possibility that insurance agents might be treated as franchisees.5 Even the famous clothing manufacturer, Gap International, found itself caught in the franchise snare. In Gabana Gulf Distribution Ltd. -

Ken Johnson Director, Product Management, Red Hat the Plan

Red Hat JBoss Middleware Integration Products Roadmap Ken Johnson Director, Product Management, Red Hat The Plan... Integration Products Overview Product-by-product • Intro • Roadmap Cross-product initiatives Wrap-up Roadmap Key Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 1 Maintenance Extended Full Support Support Life Support 2.2 2.3 2.3.1 Tentative, not yet in planning. Released – currently Dates and features speculative available to customers In planning or development phase Usual caveats apply – features and release dates can and will change Innovate faster, in a smarter way A family of a lightweight, enterprise-grade products that are ideal for open hybrid cloud environments. Management • JBoss Operations Network Tools AUTOMATE Business Rules, workflow & Processes Rules, workflow Business JBoss Portal Portal JBoss BRMS JBoss Suite BPM JBoss A-MQ JBoss Fuse JBoss Works Fuse Service JBoss Virtualization Data JBoss EAP JBoss Server Web JBoss Grid Data JBoss • • • • • • • • • • • RED HAT Confidential RED HAT T D T M o o INTEGRATE e a o o v n l l e User Interaction s s a l g o e p Applications, Data,Applications, & Events Devices m m e e Business Process n n t t Management Application Integration Physical | Virtual | Private Cloud | | Public Cloud Private Cloud Physical | Virtual User Interaction User Data Integration Data Foundation Business Process Management DataApplication Integration Integration Performance Development ACCELERATE • JBoss Developer Studio Tools Foundation Application Development, Deployment & & Deployment Development, Application ACCELERATE -

The Glenn Minnetonka Fireside Suites

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 9:00 Morning Stretches with John 1 9:30 In the News with John 10:15 The Brady Bunch (Hulu) 2:00 Afternoon Movie with RA’s: The Sound of Music (Disney+) 10:00 St. Olaf Catholic Church 9:45 Move & Groove with John 9:30 Seated Chair Exercise with 9:45 Seated Yoga Stretches 9:30 Music & Movement with 9:45 Seated Chair Exercise with 9:00 Seated Chair Exercise Mass with RA’s (YouTube) 2 10:00 Hand Massages with John 3 Kelly 4 with Kelly 5 John 6 Kelly 7 with Kelly 8 10:00 The Price is Right 10:00 Trademark Tuesday with Kelly 10:15 Wii Game with Kelly 10:00 Wheel of Fortune Game with 10:15 The Andy Griffith Show 10:45 Sunday Morning 11:00 News & Views with John 10:30 Visit the San Diego Zoo with 11:00 The Floor is Lava Game Show John (YouTube) 9:30 Music & Memory: Elvis Stretches with Alissa 11:30 How it’s Made with John Kelly (Netflix) 11:00 Virtual Music Therapy with Laura 11:00 Horoscope Readings with Kelly Presley with Kelly 11:15 International Friendship 1:30 Pastoral Care Visits with Deacon 11:00 Daily Chronicle Reading & 1:45 Music & Memory: Bing Crosby 11:30 News & Views with John 11:30 Bible Stories with Deacon Michael Michael 1:30 Afternoon Movie: Big Miracle 2:00 Chicken Soup for the Soul with 10:00 The American Bible Day Facts with Alissa Discussion with Kelly with John 2:00 Manicures with Kelly 1:45 Visit Mexico with Alissa 2:30 Unidine Smoothie Delivery (Netflix) Kelly Challenge (Netflix) 2:00 Afternoon Movie: The Fiddler on 2:30 Pastoral Care Visits with Deacon 2:30 America’s