The Beum A' Chlaidheimh Breach and the Dulnain-Findhorn Divide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of the Wildcat (Felis Silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the Conservation Status and Assessment of Conservation Activities

Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities Urs Breitenmoser, Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten February 2019 Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 2 Cover photo: Wildcat (Felis silvestris) male meets domestic cat female, © L. Geslin. In spring 2018, the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan Steering Group commissioned the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group to review the conservation status of the wildcat in Scotland and the implementation of conservation activities so far. The review was done based on the scientific literature and available reports. The designation of the geographical entities in this report, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The SWCAP Steering Group contact point is Martin Gaywood ([email protected]). Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 3 List of Content Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Summary 5 1. Introduction 7 2. History and present status of the wildcat in Scotland – an overview 2.1. History of the wildcat in Great Britain 8 2.2. Present status of the wildcat in Scotland 10 2.3. Threats 13 2.4. Legal status and listing 16 2.5. Characteristics of the Scottish Wildcat 17 2.6. Phylogenetic and taxonomic characteristics 20 3. Recent conservation initiatives and projects 3.1. Conservation planning and initial projects 24 3.2. Scottish Wildcat Action 28 3.3. -

A Project to Identify, Survey and Record the Archaeological Remains of a Farmstead at North Kinrara and a Possible Fortification

A Project to Identify, Survey and Record the Archaeological Remains of a farmstead at North Kinrara and a possible fortification on Tor Alvie, both near Aviemore, Inverness-shire June 2006 – Jan 2011 With the kind permission of Kinrara Estate Report of a Project to Identify, Survey and Record Archaeological remains of a farmstead at North Kinrara, and a possible fortification on Tor Alvie, near Aviemore, Inverness-shire by the North of Scotland Archaeological Society June 2006 – Jan 2011 Members of the team George Grant, Allan Mackenzie, Ann Wakeling, Ann Wilson, Meryl Marshall, John and Trina Wombell This report was compiled and produced by Meryl Marshall for NOSAS Front cover: main picture, the etching of the old farm house at North Kinrara from Stoddarts book of 1801 and inset, the 5th Duke of Gordon monument on the summit of Tor Alvie, constructed in 1840. Contents 1. Location of North Kinrara 3 2. Introduction and Background 3 3. Historical Background 5 4.1 Results 4.1.1 Farmstead at North Kinrara 8 4.1.2 Possible Fortification on Tor Alvie 11 4.2 Discussion 13 4.3 List of Photographs 15 1. Location of North Kinrara 2. Introduction and Background During the summers of 2004 to 2006 NOSAS members undertook a project of survey and excavation in Glen Feshie. The project also included historical research and the eventual outcome was the publication of a book, “Glen Feshie – The History and Archaeology of a Highland Glen”. One of the fascinating aspects of Glen Feshie was its associations with the Duchess of Bedford, Sir Edwin Landseer and the shooting estate in the 1820s and 1830s. -

The Sinclair Macphersons

Clan Macpherson, 1215 - 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson, 20 January 2011 Not for sale, free download available from www.reynoldmacpherson.ac.nz Clan Macpherson, 1215 to 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their traditional Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson Introduction The Clan Macpherson Museum (see right) is in the village of Newtonmore, near Kingussie, capital of the old Highland district of Badenoch in Scotland. It presents the history of the Clan and houses many precious artifacts. The rebuilt Cluny Castle is nearby (see below), once the home of the chief. The front cover of this chapter is the view up the Spey Valley from the memorial near Newtonmore to the Macpherson‟s greatest chief; Col. Ewan Macpherson of Cluny of the ‟45. Clearly, the district of Badenoch has long been the home of the Macphersons. It was not always so. This chapter will make clear how Clan Macpherson acquired their traditional lands in Badenoch. It means explaining why Clan Macpherson emerged from the Old Clan Chattan, was both a founding member of the Chattan Confederation and yet regularly disputed Clan Macintosh‟s leadership, why the Chattan Confederation expanded and gradually disintegrated and how Clan Macpherson gained its property and governance rights. The next chapter will explain why the two groups played different roles leading up to the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The following chapter will identify the earliest confirmed ancestor in our family who moved to Portsoy on the Banff coast soon after the battle and, over the decades, either prospered or left in search of new opportunities. -

Producers' Directory

CAIRNGORMS PRODUCERS’ DIRECTORY for the catering industry Contents Foreword 4 Bakery This directory is a guide for people working all been grown, bred and developed in in the catering trade and providing food the outstanding natural environment of and drink in the Cairngorms National the Cairngorms. 5 Beverages Park. The list of local producers and processors has been put together by Buying local reduces food miles. Cutting the Cairngorms National Park Authority, down the distance from “farm to fork” working in partnership with the Soil reduces road congestion, noise, disturbance, Confectionery, Association Scotland, on behalf of the wider pollution and the need for packaging and 8 food sector, as part of their Food for Life processing of certain products. Home baking & Preserves Scotland programme. Food for Life Scotland encourages more sustainable diets based This Directory has focused mainly on on local, unprocessed, seasonal and where producers within the Cairngorms National available, organic produce. We encourage Park but there are also fantastic producers you to use this directory and support local on the fringes of the Park. Whether in 10 Dairy producers whenever you can. Nairnshire, Moray, Aberdeenshire, Angus or Perthshire, quality local produce is on our Buying local supports the local economy. doorsteps. Buying local produce to use on It creates jobs and benefits local producers, your menu is good for your business, the processors and others in the supply chain; local economy and the environment. keeping employment and money in the area. 11 Fish & Seafood Future information on producers in and Buying local helps local farmers and around the Cairngorms will be updated land managers carry on working in ways regularly online at: that take care of our special landscapes for www.visitcairngorms.com/foodanddrink the future. -

Comments for Web.Xlsx

POLICY/SITE ISSUE NAME OUR REF. NAME COMMENT MODIFICATION SOUGHT Other settlements Mr Jonathan Kerfoot(01052) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Supports Other Settlements policy. Cromarty is already an established community and with the re-opening 1052/1/001 of Nigg further housing development would be seen as beneficial. Other settlements Mr John Ross(00016) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Agrees with the preferred approach to other (smaller) settlements. Considers providing some criteria are 0016/1/001 met development should go ahead. Other settlements Kilmorack Community Council(00031) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Agrees with the preferred approach to other settlements. Concerned that having developer funded Remove criterion 'whether any developer funded mitigation of 0031/1/004 mitigation mentioned means that it will be seen as an inducement to recommend. impact is offered.' Other settlements Robert Boardman(00033) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Considers that all or most criteria should be applied. 0033/1/001 Other settlements Scottish Natural Heritage(00204) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Tentatively suggests Invermoriston should have is own village chapter with more specific guidance on how 0204/1/012 the River Moriston SAC salmon and pearl mussel interests will be protected from any development pressures. Failing this, asserts that the criteria and in particular the penultimate criterion should not duplicate or contradict guidance elsewhere in the development plan - e.G. It shouldn't imply that only local natural heritage features will be taken into account. Other settlements Mr John Finlayson(00244) IMFLDP_MAIN/CONS/0 Other Settlements Believes that Abriachan should have a settlement boundary defined with the Plan that encloses client's land Addition of a mapped settlement boundary for Abriachan that 0244/1/001 as suitable for development because client's development would allow provision of sewerage system that encloses client's land as suitable for development. -

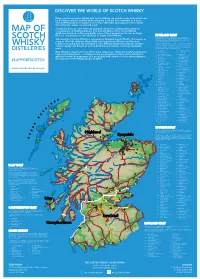

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Premises: Landmark Forest Adventure Park, Carrbridge (HLC/051/20)

Agenda 6.2 item Report HLC/051/20 no THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: THE HIGHLAND LICENSING COMMITTEE Date: 1 December 2020 Report title: Application for the renewal of a public entertainment licence – Landmark Forest Adventure Park, Carrbridge (Ward 20 – Badenoch and Strathspey) Report by: The Principal Solicitor – Regulatory Services 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report relates to an application for the renewal of a public entertainment licence. 2. Recommendation 2.2 Members are asked to determine the application in accordance with the Council’s hearing procedure. 3. Background 3.1 On 12 February 2020 an application for the renewal of a public entertainment licence was received from Visitor Centres Ltd, Landmark Forest Adventure Park, Carrbridge. A public entertainment licence is required for the water rides and the roller coaster ride located within the Visitor Centre. 3.2 In terms of the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982 (“the 1982 Act”) the Licensing Authority have twelve months (due to temporary amendments to the legislation during the coronavirus period) from receipt of the application to determine the same, therefore this application must be determined by 11 February 2021. Failure to determine the application by this time would result in the application being subject of a ‘deemed grant’ which means that a licence would require to be issued for a period of 1 year. 4. Process 4.1 Following receipt of the application a copy was circulated to the following Agencies/Services for consultation: • Police Scotland • Scottish Fire and Rescue Service • Highland Council Environmental Health Service • Highland Council Building Standards Service • Highland Council Planning Service • Highland Council Environment and Infrastructure Roads Section 5. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

SERA Presents: 10 Day Classic Scotland

DEPOSIT/PAYMENT TERMS AND CONDITIONS Optional Travel Protection Insurance Initial Deposit: $700 per person on/or before 01 November, 2021 $299 based on doube occupancy / $349 based on single occupancy Initial registration: Must be made by Credit Card. Initial reservations can (Travel protection must be added prior to fnal payment) be made by calling the Group call center number 267-585-5100 or via the SERA Presents: following dedicated webpage link: Details of coverage can be found at: www.gate1travel.com/insurance/ www.gate1travel.com/Cms/Package/2011462 Travel Protction Insurance can be added at time of registration via the call Final payment: 70 Days prior to the departure date center or via the webpage: www.gate1travel.com/Cms/Package/2011462 10 Day Classic Scotland The final payment can be made by Credit card or Check.( 5% discount for payment made by check (the discount will be reflected on the final Late Payment invoice) Full payment should be received no later than the Final Payment date listed your final group statement. Late payment fees will be assessed and CANCELLATION FEES PER PERSON are payable in full to confirm all services; for payments received more than 61 days or more prior to departure: $400 cancellation fee per person. 5 days after the Final Payment Date a 1% fee of the outstanding balance 60 days or less prior to departure: 100% of tour price will be added, and more than 10 days after the Final Payment Date a 2% fee of the outstanding balance will be added. Note: All cancellations must be made in writing. -

Your Itinerary

Britain and Ireland Explorer Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 deliver the craic for which Ireland is so renowned. London – StratforduponAvon – York – Bradford (1 Night) Hotel - Maldron Newlands Cross Discover what's 'great' about Great Britain as you kickstart your lengthy love affair Included Meals - Breakfast with Britain and Ireland in London. The multicultural capital, with all its colour, history Day 9 and culture, waves you on towards the lush green counties north as you wind your way to Stratfordupon Avon. There's time to explore the town where England's Dublin sightseeing and free time favourite bard was born and laid to rest. You could delve into his life during a visit to Embrace your playful side on this morning's sightseeing tour through Ireland's Shakespeare's Birthplace and Visitor Centre before continuing your journey to York. whimsical capital with a Local Specialist. View St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin Wander through its medieval streets to the city's geographic and spiritual heart, the Castle and Trinity College, where the 9thcentury Book of Kells, and Ireland's York Minster. Then walk along The Shambles, a street so old it was mentioned in greatest cultural treasure, is housed. This afternoon, explore Dublin your way or join the Domesday Book. Continue to your hotel in Bradford. an optional visit to one of the most important monastic sights in Europe. Your Local Specialist will bring the ancient stories of Glendalough to life and show you around Hotel - Jurys Inn the beautiful landscapes of the garden of Ireland. -

Parish Profile for Abernethy Linked with Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine

Parish Profile for Abernethy linked with Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine www.abck-churches.org.uk Church of Scotland Welcome! The church families in the villages of Abernethy, Boat of Garten, Carrbridge and Kincardine are delighted you are reading this profile of our very active linked Church of Scotland charge, based close to the Cairngorm Mountains, adjacent to the River Spey and surrounded by the forests and lochs admired and enjoyed by so many. As you read through this document we hope it will help you to form a picture of the life and times of our churches here in the heart of Strathspey. Our hope, too, is that it will encourage you to pray specifically about whether God is calling you to join us here to share in the ministry of growing and discipling God’s people plus helping us to reach out to others with the good news of Jesus Christ. Please be assured that many here are praying for the person of God’s choosing. There may be lots of questions which arise from reading our profiles. Please do not hesitate to lift the phone, or send off a quick email to any of the names on the Contacts page including our Interim Moderator, Bob Anderson. We’d love to hear from you. Church of Scotland Contents of the Profile 1. Welcome to our churches. (2) 2. Description of the person we are looking for to join our teams (4) 3. History of the linkage including a map of the villages. (5/6) 4. The Manse and its setting. -

Not Your Average Day in the Office

WELCOME ACCESSIBILITY CAPACITY CHART SPACES ACTIVITIES TEAM MEETINGS EVENTS CONFERENCES & EXHIBITIONS FOOD & DRINK GET IN TOUCH NOT YOUR AVERAGE DAY IN THE OFFICE A unique venue in the heart of the Cairngorms National Park WELCOME ACCESSIBILITY CAPACITY CHART SPACES ACTIVITIES TEAM MEETINGS EVENTS CONFERENCES & EXHIBITIONS FOOD & DRINK GET IN TOUCH A WARM HIGHLAND WELCOME AWAITS Welcome to Macdonald Aviemore Resort in the Scottish Highlands. We hope this guide gives you a flavour of the meetings, events and conferences that we can deliver from a small meeting right through to bespoke and exclusive use events. Call our Events Team on + 44 (0) 344 879 9152 Email us on [email protected] Set in 90 acres of countryside in the heart of the Cairngorms National Park you’ll feel a million miles away. Snapshot of our facilities: • Up to 30 syndicate spaces • Large tiered auditorium for 650 delegates • Peregrine Suite with views of the Cairngorms • Impressive Osprey Arena with 1000m2 space • 4-star hotels offering over 400 bedrooms • Selection of restaurants and bars • Private dining options • Exclusive use of hotel & resort options • High speed WiFi • 1,000 free car parking spaces • Easily accessible by train, plane or car WELCOME ACCESSIBILITY CAPACITY CHART SPACES ACTIVITIES TEAM MEETINGS EVENTS CONFERENCES & EXHIBITIONS FOOD & DRINK GET IN TOUCH EASILY ACCESSIBLE Located in the centre of Aviemore surrounded by the Cairngorms National Park yet just a OVERNIGHT train, plane or drive away. Here’s how simple it really is to get to our world. SLEEPER FROM LONDON TO AVIEMORE DIRECT TRAIN LINKS TO THE SOUTH We are located opposite Aviemore Train Station, just a few minutes walk away.