Bound Volume)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E812 HON

E812 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 30, 2009 Engine Repair Shop. The USS Tutuila func- of the Year by the United States Track & Field tion on Florida folk life while working for the tioned as a repair ship for the hundreds of and Cross Country Coaches Association WPA’s Federal Writers Project. As a result of small armed craft, or swift boats, used by the (USTFCCCA). her extensive anthropological research, her U.S. Navy and their South Vietnamese coun- Overall, the win marks SUNY Cortland’s writings have become invaluable sources on terparts in patrolling the numerous inland and 22nd national team title, including 16 NCAA African American life during the Harlem Ren- coastal waterways. Mr. Nissen and his fellow crowns in seven different sports. aissance. In all, Hurston wrote four novels and sailors worked around the clock to keep the Madam Speaker, I am honored to represent more than 50 published short stories, plays, swift boats functioning. They were often re- such skilled and hard-working athletes in my and essays, and she is best known for her sponsible for towing boats out of hostile areas district. Please join me in congratulating the 1937 novel ‘‘Their Eyes Were Watching God.’’ and transporting wounded sailors to safety. team and wishing them the best of luck in Madam Speaker, I would also like to recog- During his service on the USS Tutuila, Mr. their future athletic and scholarly pursuits. nize Dr. Gladys Pumariega Soler. Dr. Soler Nissen became interested in the work of the f was born in Cuba in 1930 and earned a med- medical staff and became a ‘‘striker’’ for a rat- ical degree from Havana University in 1955. -

Janet Reno, First Female US Attorney General, Dies

6A » Tuesday, November 8, 2016 » KITSAPSUN MONEY LIFE MONDAY MARKETS GOOD DAYFOR LORDE FANS INDEX CLOSE CHG DowJones Industrial Avg. 18,260 x 371.32 On the eve of her 20th birthday,the Nasdaq composite 5,166.17 x 119.80 pop idol offered asmall gift to fans: S&P 500 2,131.52 x 46.34 The promise of new music. “I want you T-note,10-year yield 1.83% x 0.06 Oil, light sweet crude $44.89 x 0.82 to see the album cover,poreover the Euro(dollarsper euro) $1.1040 y 0.0077 lyrics (the best I’ve written in my life), Yenper dollar 104.58 x 1.45 touch the merch, experiencethe live SOURCES USA TODAYRESEARCH, MARKETWATCH.COM show,” Lorde wrote in an open letter vAmericasMarkets.usatoday.com KEVIN WINTER/GETTY IMAGES published late Sunday. Nation &World Watch JanetReno,firstfemale From Gannett and wirereports vCushing, Okla.: Quake US attorneygeneral, dies damages 40-50 buildings Dozens of buildings sustained “sub- stantial damage” after a5.0-magnitude earthquakestruck an Oklahoma town ‘Fiercely independent’ leader headed Justice through tough times that’shome to one of the world’skey oil hubs,but officials said Mondaythat no Jane Onyanga-Omara damagewas reported at the oil terminal. and Kevin Johnson Cushing City Manager SteveSpears said 40 to 50 buildings were damaged in USA TODAY Sunday’searthquake, which wasthe third in Oklahoma this year with amag- JanetReno,the firstwoman nitude of 5.0orgreater.Oklahoma has to serveasU.S.attorney gener- had thousands of earthquakes in recent al, whose tenure spanned some years,with nearly all traced to the under- of the mosttumultuous periods ground injection of wastewater left over in American life, has died. -

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

Jenny Lisette Flores V Janet Reno

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA JENNY LISETTE FLORES, et al, Plaintiffs v. JANET RENO, Attorney General of the United States, et al., Defendants Case No. CV 85-4544-RJK(Px) STIPULATED SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WHEREAS, Plaintiffs have filed this action against Defendants, challenging, inter alia, the constitutionality of Defendants' policies, practices and regulations regarding the detention and release of unaccompanied minors taken into the custody of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in the Western Region; and WHEREAS, the district court has certified this case as a class action on behalf of all minors apprehended by the INS in the Western Region of the United States; and WHEREAS, this litigation has been pending for nine (9) years, all parties have conducted extensive discovery, and the United States Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of the challenged INS regulations on their face and has remanded for further proceedings consistent with its opinion; and WHEREAS, on November 30, 1987, the parties reached a settlement agreement requiring that minors in INS custody in the Western Region be housed in facilities meeting certain standards, including state standards for the housing and care of dependent children, and Plaintiffs' motion to enforce compliance with that settlement is currently pending before the court; and WHEREAS, a trial in this case would be complex, lengthy and costly to all parties concerned, and the decision of the district court would be subject to appeal by the losing parties with the final outcome uncertain; and WHEREAS, the parties believe that settlement of this action is in their best interests and best serves the interests of justice by avoiding a complex, lengthy and costly trial, and subsequent appeals which could last several more years; AILA InfoNet Doc. -

September 2003 Liberalism Reclaimed the Jury’S Still Out

William Mitchell College of Law Student Newspaper September 2003 Liberalism Reclaimed The Jury’s Still Out By Michael Welch By Lori Bower Some 800 lawyers, judges, politi- Meet Professor Peter Oh, a cians, professors and students California native with impressive gathered in Washington, D.C., credentials and teaching experience recently to call for a confident, cohe- to justice. There are now four practi- at Florida State University. Professor sive liberal jurisprudence in America. tioner chapters around the country, Oh received his law degree from the The assembled listened to a rare including one in the Twin Cities, and University of Chicago and worked speech by U.S. Supreme Court Justice some 80 chapters at law schools. The with Judge Alex Kozinski of the U.S. Ruth Bader Ginsburg and danced William Mitchell chapter was started Court of Appeals for the Ninth with Janet Reno at the American in the spring of 2002 by a handful of Circuit. He practiced law in New York, Constitution Society’s first-ever students, a number of whom have and then switched to a career in national convention, held August 1-3 since graduated and moved on to legal academia. I sat down to talk at the Capitol Hilton. The ACS event repaying their school loans. Mary with Professor Oh about his back- Professor Peter Oh – Happy to be at Mitchell, was a reassuring and invigorating Kilgus, the current chapter president, ground and approach to his first year a bit unsure of Minnesota winters experience for folks who have noted as a professor at William Mitchell. -

1 Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School 2 Public Safety

Page 1 1 MARJORY STONEMAN DOUGLAS HIGH SCHOOL 2 PUBLIC SAFETY COMMISSION MEETING 3 4 BB&T CENTER 5 CHAIRMAN'S CLUB 6 ONE PANTHER PARKWAY 7 SUNRISE, FLORIDA 33323 8 9 August 8, 2018 10 11 12 COMMISSION MEMBERS/ATTENDEES: SHERIFF BOB GUALTIERI - CHAIR 13 JASON JONES - PSC GENERAL COUNSEL CHRIS NELSON - CHIEF OF POLICE, CITY OF AUBURNDALE 14 BRUCE BARTLETT - CHIEF ASSISTANT STATE ATTORNEY, SIXTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT 15 RICHARD SWEARINGEN - COMMISSIONER FLORIDA DEPARTMENT 16 OF LAW ENFORCEMENT MAX SCHACHTER - VICTIM PARENT 17 LARRY ASHLEY - SHERIFF, OKALOOSA COUNTY MELISSA LARKIN SKINNER - CEO, CENTERSTONE OF FLORIDA 18 PAM STUART - COMMISSIONER OF EDUCATION JUSTIN SENIOR - SECRETARY, AHCA 19 CHRISTI DALY, SECRETARY, DEPT OF JUVENILE JUSTICE MICHAEL CARROLL - SECRETARY, DCF 20 JAMES HARPRING - UNDERSHERIFF/GC, INDIAN RIVER COUNTY 21 DESMOND BLACKBURN - SUPERINTENDENT, BREVARD COUNTY GRADY JUDD - SHERIFF, POLK COUNTY 22 DOUG JUDD - SCHOOL BOARD MEMBER, CITRUS COUNTY LAUREN BOOK - SENATOR, DISTRICT 32 23 RYAN PETTY - VICTIM PARENT MARSHA POWERS - SCHOOL BOARD MEMBER, MARTIN COUNTY 24 KEVIN LYSTAD - PRESIDENT, FLORIDA POLICE CHIEF ASSOC CHRISTINA LINTON - COMMISSION STAFF, FDLE 25 Veritext Legal Solutions 800-726-7007 305-376-8800 Page 2 1 (Thereupon, the meeting is called to order:) 2 CHAIR: We're getting ready to start here, 3 if everyone would take their seats. Please 4 stand and join me in a moment of silence in 5 memory of the victims of the Stoneman Douglas 6 tragedy. 7 (Thereupon, a moment of silence is had.) 8 CHAIR: Thank you. Please join me in the 9 pledge. 10 (Thereupon, the pledge of allegiance is stated.) 11 CHAIR: Thank you. -

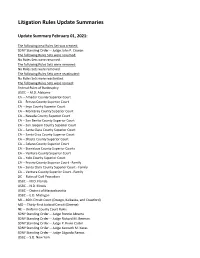

2021-02-01 Litigation Rules Update Summaries

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary February 01, 2021: The following new Rules Set was created: SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge John P. Cronan The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: Federal Rules of Bankruptcy USDC ‐‐ M.D. Alabama CA ‐‐ Amador County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Inyo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Monterey County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Nevada County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Benito County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Joaquin County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Cruz County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Shasta County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Solano County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Stanislaus County Superior Courts CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Yolo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court ‐ Family DC ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure USBC ‐‐ M.D. Florida USBC ‐‐ N.D. Illinois USBC ‐‐ District of Massachusetts USBC ‐‐ E.D. Michigan MI ‐‐ 46th Circuit Court (Otsego, Kalkaska, and Crawford) MO ‐‐ Thirty‐First Judicial Circuit (Greene) NE ‐‐ Uniform County Court Rules SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Ronnie Abrams SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Richard M. Berman SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge P. Kevin Castel SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Kenneth M. Karas SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Edgardo Ramos USBC ‐‐ S.D. New York NY Appellate Division, Rules of Practice NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, First Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Second Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Third Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Fourth Department USDC ‐‐ District of North Dakota USDC ‐‐ N.D. -

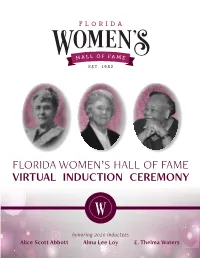

The 2020 Induction Ceremony Program Is Available Here

FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME VIRTUAL INDUCTION CEREMONY honoring 2020 inductees Alice Scott Abbott Alma Lee Loy E. Thelma Waters Virtual INDUCTION 2020 CEREMONY ORDER OF THE PROGRAM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women CONGRATULATORY REMARKS Jeanette Núñez . Florida Lieutenant Governor Ashley Moody . Florida Attorney General Jimmy Patronis . Florida Chief Financial Officer Nikki Fried . Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Charles T. Canady . Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice ABOUT WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME & KIOSK Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee 2020 FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME INDUCTIONS Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee HONORING: Alice Scott Abbott . Accepted by Kim Medley Alma Lee Loy . Accepted by Robyn Guy E. Thelma Waters . Accepted by E. Thelma Waters CLOSING REMARKS Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women 2020 Commissioners Maruchi Azorin, M.B.A., Tampa Rita M. Barreto, Palm Beach Gardens Melanie Parrish Bonanno, Dover Madelyn E. Butler, M.D., Tampa Jennifer Houghton Canady, Lakeland Anne Corcoran, Tampa Lori Day, St. Johns Denise Dell-Powell, Orlando Sophia Eccleston, Wellington Candace D. Falsetto, Coral Gables Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, Ft. Myers Senator Gayle Harrell, Stuart Karin Hoffman, Lighthouse Point Carol Schubert Kuntz, Winter Park Wenda Lewis, Gainesville Roxey Nelson, St. Petersburg Rosie Paulsen, Tampa Cara C. Perry, Palm City Rep. Jenna Persons, Ft. Myers Rachel Saunders Plakon, Lake Mary Marilyn Stout, Cape Coral Lady Dhyana Ziegler, DCJ, Ph.D., Tallahassee Commission Staff Kelly S. Sciba, APR, Executive Director Rebecca Lynn, Public Information and Events Coordinator Kimberly S. -

European Journal of American Studies, 10-1 | 2015 Introduction: North American Women in Politics and International Relations 2

European journal of American studies 10-1 | 2015 Special Issue: Women in the USA Introduction: North American Women in Politics and International Relations Isabelle Vagnoux Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10463 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.10463 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Isabelle Vagnoux, “Introduction: North American Women in Politics and International Relations”, European journal of American studies [Online], 10-1 | 2015, document 1.1, Online since 26 March 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10463 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/ejas.10463 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Introduction: North American Women in Politics and International Relations 1 Introduction: North American Women in Politics and International Relations Isabelle Vagnoux 1 “We can’t be more machista than the Argentines,” former President Bill Clinton reportedly quipped in 2008, when his wife Hillary Rodham Clinton was battling in the Democratic primaries of the presidential election, shortly after Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner had been elected President of Argentina in 2007, and following Michelle Bachelet’s election in Chile the year before. The United States more ‘machista’ than Latin America in politics ? A challenging issue that was tackled during the French Institute of the Americas’ annual conference, December 4-6, 2013, which gathered over 150 scholars working on Women in the Americas at Aix-Marseille Université, France. The selection that follows was part of a panel devoted to Women, politics and international relations in the Americas. Only those focusing on the United States and Canada are presented in this issue of the European Journal of American Studies. -

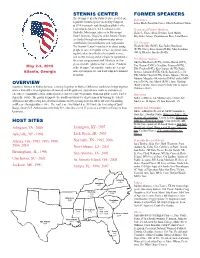

Fact Sheet 10.Indd

STENNIS CENTER FORMER SPEAKERS The Stennis Center for Public Service is a federal, First Ladies legislative branch agency created by Congress Laura Bush, Rosalynn Carter, Hillary Rodham Clinton in 1988 to promote and strengthen public service leadership in America. It is headquartered in Presidential Cabinet Members Starkville, Mississippi, adjacent to Mississippi Elaine L. Chao, Alexis Herman, Lynn Martin, State University. Programs of the Stennis Center Kay Coles James, Condoleezza Rice, Janet Reno are funded through an endowment plus private contributions from foundations and corporations. U.S. Senators The Stennis Center’s mandate is to attract young Elizabeth Dole (R-NC), Kay Bailey Hutchison people to careers in public service, to provide train- (R-TX), Nancy Kassebaum (R-KS), Mary Landrieu ing for leaders in or likely to be in public service, (D-LA), Blanche Lincoln (D-AR) and to offer training and development opportunities U.S. Representatives for senior congressional staff, Members of Con- Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Corrine Brown (D-FL), gress, and other public service leaders. Products May 2-3, 2010 Eva Clayton (D-NC), Geraldine Ferraro (D-NY), of the Stennis Center include conferences, semi- Tillie Fowler (R-FL), Kay Granger (R-TX), Eddie Atlanta, Georgia nars, special projects, and leadership development Bernice Johnson (D-TX), Sheila Jackson Lee (D- programs. TX), Marilyn Lloyd (D-TN), Denise Majette ( D-GA), Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky (D-PA) Cynthia McK- inney (D-GA), Sue Myrick (R-NC), Anne Northup OVERVIEW (R-KY), Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL), Karen Southern Women in Public Service: Coming Together to Make a Difference conference brings together Thurman (D-FL) women from different backgrounds—Democrats and Republicans, stay-at-home mothers and business executives, community leaders, political novices and veterans—to promote women in public service leader- Governors ship in the South. -

Women in US Politics: Democratic Women Firsts

Women in U.S. Politics: Democratic Women Firsts PRESIDENTIAL APPOINTEE: With the full backing, and sometimes prodding, of his wife Eleanor, Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt was the first U.S. President to highlight women and their issues. President Clinton has continued this Democratic tradition and made women full partners in government. • Franklin Roosevelt was the first President to appoint a woman to his cabinet. In 1933, Frances Perkins became the Secretary of Labor. He was also the first President to appoint an African American woman. In 1935, Mary Mcleod Bethune, founder of the National Council of Negro Women, was named head of the Office of Minority Affairs. • Under the leadership of President Clinton, women make up 42% of appointments. Many of them ~re the first women to hold their positions, including Attorney General Janet Reno, Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary, who is also the first African-American to serve in that position, National Economic Advisor Laura D' Andrea Tyson, and Deputy Chief of Staff Evelyn Lieberman. • President Clinton nominated 45 women out of a total 141 nominees to the federal bench. PRESIDENTIAL AND VICE PRESIDENTIAL: The Democratic Party is the only major party to have a woman as Vice Presidential candidate and nominee. • In 1924 Democrat Lena Jones Springs became the first woman to have her name placed in nomination as the vice presidential candidate of a major political party. She was nominated from her home state, -South Carolina, at the Democratic Convention in New York City. • In 1984, the Democratic Party became the first major political party to nominate a woman for Vice President. -

2020-12-31 FC-DA Litigation Rules Update Summaries

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary December 31, 2020: The following new Rules Sets were created: CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge John W. Holcomb CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Pedro V. Castillo CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Stanley Blumenfeld Jr. The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: USBC ‐‐ E.D. Arkansas USBC ‐‐ W.D. Arkansas CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Mark C. Scarsi CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Mag. Jacqueline Chooljian USDC ‐‐ S.D. California USDC ‐‐ N.D. California ‐‐ ADR NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge William Alsup USBC ‐‐ E.D. California California Rules of Court ‐‐ Appeals California CCP and CRC CA ‐‐ Kings County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Placer County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Family Law CA ‐ California Criminal Procedure California Unlawful Detainer CA ‐‐ Office of Administrative Hearings USDC ‐‐ M.D. Georgia MA ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure ND ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure OH ‐‐ Trumbull County Court of Common Pleas ‐ General SC ‐‐ Magistrate's Court SC ‐‐ Court‐Annexed ADR Rules SD ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, Austin Division USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, El Paso and Waco Divisions USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, Midland‐Odessa Divisions USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, San Antonio Division WA ‐‐ Chelan County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Clallam County Superior Court WA ‐‐ King County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Skagit County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Yakima County Superior Court Update Summary November 30, 2020: The following new Rules Sets were created: CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Mark C.