Creative Industry Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Places to Go, People to See Thursday, Feb

Versu Entertainment & Culture at Vanderbilt FEBRUARY 28—MARCH 12,2, 2008 NO. 7 RITES OF SPRING PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, FEB. 28 FRIDAY, FEB. 29 SATURDAY 3/1 Silverstein with The Devil Wears Prada — Rocketown John Davey, Rebekah McLeod and Kat Jones — Rocketown Sister Hazel — Wildhorse Saloon The Regulars Warped Tour alums and hardcore luminaries Silverstein bring their popular Indiana native John Davey just might be the solution to February blues — his unique pop/ Yes, they’re still playing together and touring. Yes, they can still rock sound to Nashville. The band teamed up with the Christian group The Devil folk sound is immediately soothing and appealing and is sure to put you in a good mood. with the best of ’em. Yes, you should go. Save all your money this THE RUTLEDGE Wears Prada for a long-winded U.S. tour. ($5, 7 p.m.) 401 Sixth Avenue South, 843-4000 week for that incredibly sweet sing-along to “All For You” (you know 410 Fourth Ave. S. 37201 ($15, 6 p.m.) 401 6th Avenue S., 843-4000 you love it). ($20-$45, 6 p.m.) 120 Second Ave. North, 902-8200 782-6858 Music in the Grand Lobby: Paula Chavis — The Frist Center for the Steep Canyon Rangers — Station Inn Red White Blue EP Release Show — The 5 Spot Visual Arts MERCY LOUNGE/CANNERY This bluegrass/honky-tonk band from North Carolina has enjoyed a rapid Soft rock has a new champion in Red White Blue. Check out their EP Nashville’s best-kept secret? The Frist hosts free live music in its lobby every Friday night. -

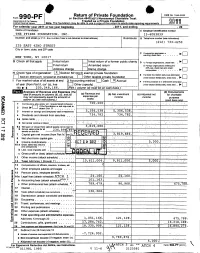

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

Report to the Community on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion December 1, 2020 Contents

Report to the Community on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion December 1, 2020 Contents Introduction .......................................... 1 Our Community .......................................... 3 LPM Workforce .......................................... 4 LPM Leadership .......................................... 5 Newsroom .......................................... 7 90.5 WUOL Classical .......................................... 12 91.9 WFPK Independent .......................................... 14 Events .......................................... 17 Board of Directors .......................................... 20 Community Advisory Board .......................................... 22 Louisville Public Media informs, inspires and empowers through independent news, music, education and experiences that reflect our diverse community. For decades, we’ve worked to deliver on that mission. But we haven’t always gotten it right. As a public media organization, LPM must strive to represent the community we serve in our staff, programming, community presence and governance. We reiterated that commitment earlier this year in our statement on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. We have made significant strides in diversifying our teams in recent years, but our culture has lagged in fully embracing new and different voices. Throughout our history, we have left out members of our community — from our staff, stories, music mixes and events. We have under-represented Black people and other people of color in what we do, on our staff and in our coverage -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Dance the Big Bang — by Universes

MILL CALENDAR S CYbrarY LITERARY Movie/Book Club — The group will discuss The CarrbORO Branch LibrarY Lovely Bones and the novel by Alice Sebold on Ongoing Events — Storytime, Saturdays at which the film is based. Participants that have 10:30am; Toddler Time, Thursdays, 4pm; Enter- only seen the movie or only read the book are tainment Adventures with family fun programs welcome. Jan. 28, 7pm. 100 N. Greensboro St., featuring dancing, song, animals, and sometimes 918-7387, [email protected], co.orange. magic, third Sunday of every month at 3pm. nc.us/library/cybrary Chapel Hill PUblic LibrarY MCIntYre’S Ongoing Events — Story Time, for ages 3-6; Author Events — Writer Sam Stephenson discusses Junior Book Club, for readers grades 1-3; Time for The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Toddlers, for stories, songs and activities; Baby Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957-1965. Jan. Time, for children between 6 and 18 months; Teen 9, 11am. Book Club, for teens in grades 6 and up; Book- Janice Y.K. Lee reads from The Piano Teacher. Jan. 13, worms Club, for grades 3-6, each month children 2pm. in this program read and discuss different novels Neil Sheehan, author of Pulitzer Prize-winner A Bright from a list of titles nominated for the N.C. Shining Lie, will read from A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Children’s Book Award. Dates and times vary. Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon. Jan. 13, 4pm. The Big Bang Meet the Author Tea — Meet George Baroff. Larry Rochelle reads from his latest thriller, Murder on 15/501. -

PRNDI Awards 2018 Division AA (Stations with 16 Or More Full-Time

PRNDI Awards 2018 Division AA (Stations with 16 or more full-time news staff) Arts Feature First Place KUT 90.5 FM - “Moments” Second Place KCUR - “Getting Dragged Down By The News? This Kansas City Gospel Singer Has A Message For You” Best Multi-Media Presentation First Place WFPL / Kentucky Public Radio - “The Pope's Long Con” Second Place KERA - 90.1 Dallas - “One Crisis Away: No Place To Go” Best Use of Sound First Place Michigan Radio - “Artisans of Michigan: Making Marimbas” Second Place Georgia Public Broadcasting - “Breathing In ATL's Underwater Hockey Scene” Best Writing First Place KJZZ 91.5 FM - “Christmas Stuffing: AZ Class Beginners to Taxidermy” Second Place KJZZ 91.5 FM - “Earth & Bone - Havasupai Stand Up to Mining Company” pg. 1 PRNDI Awards 2018 Breaking News First Place KUOW-FM - “Train Derailment” Second Place Georgia Public Broadcasting - “Hurricane Irma” Call-in Program First Place WBUR - “Free Speech Controversy Erupts At Middlebury College” Second Place Vermont Public Radio - “Who Gets To Call Themselves A 'Vermonter'?” Commentary First Place KUOW-FM - “I stopped learning Farsi. I stopped kissing the Quran. I wanted to be normal” Second Place KCUR - “More Than Just Armchair Gamers” Continuing Coverage First Place Chicago Public Radio/WBEZ - “Every Other Hour” Second Place St. Louis Public Radio - “Stockley Verdict and Ongoing Protests” Enterprise/Investigative First Place KERA - 90.1 Dallas - “The West Dallas Housing Crisis” Second Place KJZZ 91.5 FM - “On The Inside: The Chaos of AZ Prison Health Care” pg. 2 PRNDI Awards 2018 Interview First Place KCFR - Colorado Public Radio - “The Aurora Theater Shooting Recasts In Sickness And In Health' For One Family” Second Place WHYY - FM - “Vietnam War memories” Long Documentary First Place Michigan Radio - “Pushed Out: A documentary on housing in Grand Rapids” Second Place KUT 90.5 FM - “Texas Standard: The Wall” Nationally Edited Breaking News First Place KERA - 90.1 Dallas - “Rep. -

Public Affairs

PUBLIC AFFAIRS MISSION STATEMENT: The Division of Public Affairs at Western Kentucky University serves the University community by providing honest, timely and useful information to all internal and external stakeholders and is committed to building positive relationships on behalf of WKU among the communities within our reach and throughout local, state and federal governments, the media and the general public. The Division supports all aspects of the University’s strategic plan and its vision to become “A Leading American University with International Reach.” PROGRAM INFORMATION: The offices of Media Relations, Marketing and Communications, Campus and Community Events, and Ceremonies and Special Events provide vital services to all divisions and colleges of WKU and to the public. The Office of Government and Community Relations serves as the University’s primary advocate for the public interests of WKU and higher education in Kentucky and seeks to build goodwill at all levels of government and among the communities in our service region. WKU Public Broadcasting provides public service broadcasting to the community, professional training for students, and creates and distributes media content that serves WKU and the citizens of Kentucky. This unit is responsible for the operation of WKU Public Radio, WKU-PBS, The Hilltopper Sports Satellite Network, and WKU's two CATV systems. GOALS/ANTICIPATED PROGRAM ACTIVITIES: The Public Affairs division supports the University’s strategic goals and our vision to become “A Leading American University with International Reach” by focusing on the following programs and activities: . Government and Community Relations serves as WKU’s liaison to local, state and federal governments, maintaining a presence in Frankfort, KY, in Washington, DC, and throughout the University’s service region. -

Qué Es El Tanned Tin?

¿Qué es el Tanned Tin? El Tanned Tin es el festival de invierno por excelencia, el primero con un éxito y continuidad que dura más de una década, siendo ésta su decimotercera edición (la séptima consecutiva en Castellón tras su etapa en Santander), siempre independiente en la confección de su cartel y sin otro interés que el artístico. Plantea un espacio único (el Teatro Principal) donde se puede escuchar la música con una calidad inigualable y la comodidad propia de un recinto acogedor. Y como un punto extra, la cercanía que muestran los artistas, que se mezclan con total naturalidad con el público que acude al evento. Además, se programan matinales de lujo en (sala por confirmar). Con entrada libre para los portadores de la pulsera del festival hasta completar aforo, podremos ver actuaciones de viernes a domingo y de 12 a 15 horas. ¿Qué lo hace diferente? El Tanned Tin mantiene su filosofía de presentar un cartel lleno de futuras estrellas de la escena independiente, nombres que ahora puede que no suenen a la mayoría del público y prensa pero que en unos meses serán los grandes protagonistas de los grandes festivales. No en vano fue en el Tanned Tin donde artistas de la talla de Antony & the Johnsons, Deerhunter, Okkervil River, Final Fantasy, Deertick, Beach House, The Decemberists, Xiu Xiu, Animal Collective, CocoRosie o M.Ward dieron sus primeros conciertos en nuestro país. Buscamos dar la oportunidad al público más inquieto de conocer en su mejor momento a artistas de todo tipo (folk, electrónica, pop de vanguardia, rock arriesgado, etc.) que, además, se sienten orgullosos de formar parte del cartel debido a su reputación fuera de nuestras fronteras. -

Arts Calendar Music Calendar

PAGE 2 — Thursday, August 23, 2007 The Carrboro Citizen HE ILL This Week - August 24, 2007 - August 30 T M Tuesday Let it rain Friday Sunday Thursday Cat’s Cradle hosts Weaver Street Check out the Wednesday Suddenly, on Tuesday, the The Pietasters Saturday Market’s Jazz ArtsCenter’s Do you enjoy both Deep Dish wind kicked up and in swirls CD release show. Another CD release Brunch Series “Brushes With art and nature? Theater presents along Main Street, rippling Also playing are party, and this continues. Life,” an exhibit How about “Of “How I Got That The Slackers, one is free. Come Performing at 11 that looks at Field, Forest & Story,” a comedy the awnings, about a confused WARP signs and Steadfast see Schooner, a.m. this week Monday mental illness Fancy,” works United and Erie Choir, North through art. war reporter. & WOOF are The Richard Do I hear by The Guild of potted flora. Antagonizers. Elementary, Wes Tazewell Quartet. Ends September Natural Science It’s “cheap dish” Dead leaves a fiddle? It 8. night, so all Doors open at 8. Phillips, and The Food AND music? must be the Illustrators from parched $12 Strugglers at the No way! Carolinas tickets are $7. Bluegrass Show is at 7:30. trees and bushes and all Cradle. Explosion at Chapter. Through kinds of other debris got The Cave! September 30 and kicked up. A crape myrtle free at the Chapel Hill Museum. in front of the Bank of America building lost a good-sized branch. Then there cut loose a downpour evenings by appt. -

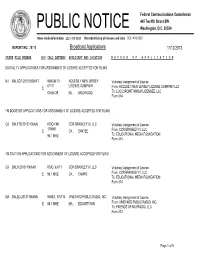

Broadcast Applications 11/12/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28113 Broadcast Applications 11/12/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NJ BALCDT-20131030AFT WMGM-TV ACCESS.1 NEW JERSEY Voluntary Assignment of License 61111 LICENSE COMPANY E From: ACCESS.1 NEW JERSEY LICENSE COMPANY LLC CHAN-36 NJ , WILDWOOD To: LOCUSPOINT WMGM LICENSEE, LLC Form 314 FM BOOSTER APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CA BALFTB-20131106AAI KSIQ-FM1 CCR-BRAWLEY IV, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License 178665 E CA , SANTEE From: CCR-BRAWLEY IV, LLC 96.1 MHZ To: EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CA BALH-20131106AAH KSIQ 63471 CCR-BRAWLEY IV, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License E 96.1 MHZ CA , CAMPO From: CCR-BRAWLEY IV, LLC To: EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION Form 314 MA BALED-20131106ANN WMEX 175715 VINEYARD PUBLIC RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 88.7 MHZ MA , EDGARTOWN From: VINEYARD PUBLIC RADIO, INC. To: FRIENDS OF MVYRADIO, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 9 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28113 Broadcast Applications 11/12/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BAPFT-20131106AAA K256CB 148484 GWENDOLYNN TELLEZ Voluntary Assignment of Construction Permit E 99.1 MHZ TX , SHINER From: WENDOLYNN TELLEZ To: CARLOS LOPEZ Form 345 FM AUXILIARY TRANSMITTING ANTENNA APPLICATIONS FOR AUXILIARY PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING CT BXPH-20131106AGN WTIC-FM 66465 CBS RADIO STATIONS INC. -

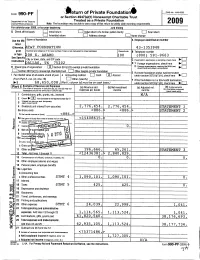

I -Eturn of Private Foundation Form 990-PF

r OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I - eturn of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2009 For calendar year 2009 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply initial return Initial return of a former public charily 0 Final return Amended return = Address change 0 Name change Use the IRS Name of foundation A Employer identification number label. Otherwise , AT&T FOUNDATION 43-1353948 print Number and street (or P O box number if mall is not delivered to street address) Roorr3suite B Telephone number ortype . 08 S. AKARD 100 ( 800 ) 591-9663 See Specific City or town , state , and ZIP code SeerSp!cIInst ructions C It exemption application is pending , check here 10' El ALLAS TX 7 5 2 0 2 D 1 Foreign organizations , check here ► X 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, 10. H Check type of organization Section 501 ()()c 3 exempt private foundation check here and attach computation El 0 Section 4947 (a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair marketvalue of all assets at end of year J Accounting method = Cash OX Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F the fou ndation is Ina 60-month terminatiore n $ 6 8 6 5 0 0 0 8 . -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION News Media Information (202) 418-0500 445 12th Street, S.W., TW-A325 Fax-On-Demand (202) 418-2830 Washington, DC 20554 Internet:http://www.fcc.gov ftp.fcc.gov Report Number: 1898 Date of Report: 08/04/2004 Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Site-By-Site Action Below is a listing of applications that have been acted upon by the Commission. AA - Aviation Auxiliary Group File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0001823815 07/30/2004 WQAS778 CALIFORNIA, STATE OF NE G R994589 07/27/2004 KP6693 INDIAN RIVER, COUNTY OF RO K AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0001686598 07/27/2004 WQAR929 MC ALESTER, CITY OF AM G 0001810076 07/27/2004 WQAR928 Hummel Aviation LLC AM G 0001818439 07/27/2004 KJK8 ATLANTIC AVIATION CORPORATION CA G 0001818440 07/27/2004 WBJ6 ATLANTIC AVIATION CORPORATION CA G 0001820615 07/28/2004 WLM7 State of Montana, Aeronautics Division CA G 0001822396 07/29/2004 WDT73 AERONAUTICAL RADIO INC CA G 0001823179 07/30/2004 WPUJ955 Aeronautical Radio Inc CA G 0001808090 07/27/2004 WPQ3 ADJUSTERS SERVICE CORP DBA REDLANDS AVIATION MD D 0001669967 07/25/2004 City of Ardmore NE D 0001772995 07/27/2004 WQAR930 Aeronautical Radio Inc NE G 0001773223 07/27/2004 WQAR931 Aeronautical Radio Inc NE G 0001773325 07/27/2004 WQAR932 Aeronautical Radio Inc NE G Page 1 AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0001773427 07/27/2004 WQAR933 Aeronautical Radio Inc NE G 0001769905 07/27/2004 WQJ8 State of Montana, Aeronautics Division RO G 0001771970 07/27/2004 KCJ8 SHARP COUNTY REGIONAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY RO G 0001773242 07/27/2004 WOM3 SEBRING FLIGHT CENTER RO G 0001773635 07/27/2004 KPT8 SUPERIOR AVIATION INC RO G 0001774988 07/27/2004 KJH6 ARIETTA, TOWN OF RO G 0001819240 07/27/2004 WNU2 TUOLUMNE, COUNTY OF RO D 0001820007 07/28/2004 WKY3 CALIFORNIA, STATE OF RO G AI - Aural Intercity Relay File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0001723713 07/29/2004 WQAS595 JOSE J.