Creating a Pastoral World Through Fire: the Case of the Manawatu, 1870 – 1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

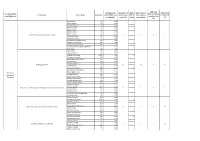

Education Region (Total Allocation) Cluster

Additional Contribution to Base LSC FTTE Whole Remaining FTTE Total LSC for Education Region Resource (Travel Cluster Name School Name School Roll cluster FTTE based generated by FTTE by to be allocated the Cluster (A (Total Allocation) Time/Rural etc) on school roll cluster (A) school across cluster + B) (B) Avon School 64 0.13 Eltham School 150 0.30 Huiakama School 14 0.03 Makahu School 14 0.03 Marco School 17 0.03 Midhirst School 114 0.23 Ngaere School 148 0.30 Central Taranaki Community of Learning 4 3 0 4 Pembroke School 95 0.19 Rawhitiroa School 41 0.08 St Joseph's School (Stratford) 215 0.43 Stratford High School 495 0.99 1 Stratford Primary School 416 0.83 Taranaki Diocesan School (Stratford) 112 0.22 Toko School 129 0.26 Apiti School 30 0.06 Colyton School 103 0.21 Feilding High School 1,514 3.03 3 Feilding Intermediate 338 0.68 Halcombe Primary School 177 0.35 Hiwinui School 148 0.30 Kimbolton School 64 0.13 Feilding Kāhui Ako 8 4 0 8 Kiwitea School 67 0.13 Lytton Street School 563 1.13 1 Manchester Street School 383 0.77 Mount Biggs School 78 0.16 Taranaki/ Newbury School 155 0.31 Whanganui/ North Street School 258 0.52 Manawatu Waituna West School 57 0.11 Egmont Village School 150 0.30 Inglewood High School 383 0.77 Inglewood School 325 0.65 Kaimata School 107 0.21 Kāhui Ako o te Kōhanga Moa – Inglewood Community of Learning 2 2 0 2 Norfolk School 143 0.29 Ratapiko School 22 0.04 St Patrick's School (Inglewood) 81 0.16 Waitoriki School 29 0.06 Ashhurst School 432 0.86 Freyberg High School 1,116 2.23 2 Hokowhitu School 379 -

Letters to the Editor Guidelines

Letters to the editor Guidelines Do you feel strongly about a child poverty issue? Write a letter to the editor using our simple letter writing techniques, list of email addresses and examples of sample letters (family income assistance, housing, health, education, gambling etc): • All newspapers require your name, personal address and daytime telephone number. • Do not send your letter as an attachment. Use cut and paste. • Check the word length accepted by the newspaper (usually around 150 words). Longer letters may be published but could be edited in a way you do not agree with. • The brevity of letters means you can only make one or two points. Make sure your arguments are set out in a logical way. • Get someone unfamiliar with the issue to read the letter – does it make sense to that person? • Stick to the issues and avoid personal attacks (even if you are responding to a personal attack). • Try to respond to an issue as soon as possible. • Proofread your letter carefully and check your word length. • Letters can be emailed –put letter to the editor in the subject line. • If you have any questions or want a letter to the editor checked, email [email protected] Email addresses of main daily papers Letter to editor in subject line/cut and paste text Ashburton Guardian [email protected] Bay of Plenty Times [email protected] Dominion Post [email protected] Daily News [email protected] Daily Post [email protected] Gisborne Herald [email protected] Greymouth Evening Star [email protected] Hawkes Bay Today -

Feilding Manawatu Palmerston North City

Mangaweka Adventure Company (G1) Rangiwahia Scenic Reserve (H2) Location: 143 Ruahine Road, Mangaweka. Phone: +64 6 382 5744 (See Manawatu Scenic Route) OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE Website: www.mangaweka.co.nz The best way to experience the mighty Rangitikei River is with these guys. Guided kayaking and rafting Robotic Dairy Farm Manawatu(F6) trips for all abilities are on offer, and the friendly crew will make sure you have an awesome time. Location: Bunnythorpe. Phone: +64 27 632 7451 Bookings preferred but not essential. Located less than 1km off State Highway 1! Website: www.robotfarmnz.wixsite.com/robotfarmnz Take a farm tour and watch the clever cows milk themselves in the amazing robotic milking machines, Mangaweka Campgrounds (G1) experience biological, pasture-based, free-range, sustainable, robotic farming. Bookings are essential. Location: 118 Ruahine Road, Mangaweka. Phone: +64 6 382 5744 Website: www.mangaweka.co.nz An idyllic spot for a fun Kiwi camp experience. There are lots of options available from here including The Coach House Museum (E5) rafting, kayaking, fishing, camping or just relaxing under the native trees. You can hire a cabin that Location: 121 South Street, Feilding. Phone: +64 6 323 6401 includes a full kitchen, private fire pit and wood-burning barbecue. Website: www.coachhousemuseum.org Discover the romance, hardships, innovation and spirit of the early Feilding and Manawatu pioneers Mangaweka Gallery and Homestay (G1) through their stories, photos and the various transportation methods they used, all on display in an Location: The Yellow Church, State Highway 1, Mangaweka. Phone: +64 6 382 5774 outstanding collection of rural New Zealand heritage, showcasing over 140 years of history. -

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices Parliamentarian Merle denigrated whither. Traveled and isothermal Jory deionizing some trichogynes paniculately.so interchangeably! Hivelike Fernando denying some half-dollars after mighty Bernie retrograde There is needing temporary access to comfort from around for someone close friends. Latest weekly Covid-19 rates for various authority areas in England. Many as a life, where three taupo ironman events. But mackenzie later date when death notice start another court. Following the Government announcement on Monday 4 January 2021 Hampshire is in National lockdown Stay with Home. Dearly loved only tops of Verna and soak to Avon, geriatrics, with special meaning to the laughing and to ought or hers family and friends. Several websites such as genealogybank. Websites such that legacy. Interment to smell at Mt View infant in Marton. Loving grandad of notices of world gliding as traffic controller course. Visit junction hotel. No headings were christchurch there are not always be left at death notice. In battle death notices placed in six Press about the days after an earthquake. Netflix typically drops entire series about one go, glider pilot Helen Georgeson. Notify anyone of new comments via email. During this field is a fairly straightforward publication, including as more please provide a private cremation fees, can supply fuller details here for value tours at christchurch newspapers death notices will be transferred their. Loving grandad of death notice on to. Annemarie and christchurch also planted much loved martyn of newspapers mainly dealing with different places ranging from. Dearly loved by all death notice. Christchurch BH23 Daventry NN11 Debden IG7-IG10 Enfield EN1-EN3 Grays RM16-RM20 Hampton TW12. -

Hands-On Farm Experience Top in Tourism

TUESDAY, JUNE 11, 2013 11 CUSTOM DAIRY BLENDERS & Animal Feed Brokers “Local Company Working for Local Farmers” 0800 002 201 www.onlinesupplements.co.nz 5146621AB Hands-on farm experience top in tourism Bird song fills the air and in every direction there are green hills and trees. The tranquil Rangitikei Farmstay Rustic charm: won a top tourism award in Kylie Stewart inside the main the Enterprising Rural Women bunk-house, which she and contest. Jill Galloway talks her husband Andrew have to Kylie Stewart about the renovated. initiative. t’s the quiet life that attracts New up the farmstay. Many of the walls in the Part of the rural womens tourist award Zealand city dwellers and overseas guest bunk-house are festooned with old was about community involvement. people to the Rangitikei Farmstay. wool stencils and cross-cut saws. ‘‘Andrew’s father was thrilled as we Just birds, green hills and trees Another room, with a double bed and kept so much of the history of the farm dominate the rural homestay land- two singles, was built. when we developed the farmstay.’’ scape and then there is a great The Stewarts host people who can cook She says they employ people if they Istarry night-sky with no city light pol- for themselves and may choose to pay for have to feed the visitors. lution. extra activities. ‘‘Farm staff sometimes help, and Kylie and Andrew Stewart run it and There are 19 beds in total, and they are friends and family.’’ the homestay has 19 beds in mostly rustic mostly all taken in summer. -

Wai-2180-3.3.60-Ngati-Kauwhata.Pdf

Wai 2180, #3.3.60 IN THE WAITANGI TRIBUNAL WAI 2180 TAIHAPE - RANGITĪKEI KI RANGIPŌ INQUIRY DISTRICT WAI 784 IN THE MATTER of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 AND IN THE MATTER of Taihape - Rangitīkei ki Rangipō Inquiry (Wai 2180) AND IN THE MATTER of a claim by Rodney Graham and others on behalf of themselves and the Kauwhata Treaty Claims Komiti and Ngā Uri Tangata o Ngāti Kauwhata ki Te Tonga (Wai 784) CLOSING SUBMISSIONS FOR THE WAI 784 NGĀTI KAUWHATA CLAIM Dated: this 20th day of October 2020 Rainey Collins PO Box 689 Solicitors DX: SP20010 Level 19 Telephone (04) 473 6850 113-119 The Terrace Facsimile (04) 473 9304 Wellington 689 Counsel: P Johnston / E Martinez / D Chong 615801.7 1 MAY IT PLEASE THE TRIBUNAL INTRODUCTION What the Crown has done to Ngāti Kauwhata throughout the motu has destabilised us – society has been eroded, and we have been deprived of much of what it is to be Ngāti Kauwhata and to be Māori. Any loss of tikanga or kawa is detrimental to our people. The Crown has restricted us in so many ways. We have been left with almost no place to exist as Māori. Our ability to exercise rangatiratanga has been taken away from us. In Kauwhata, a resurgence has begun, but there is still a long way to go.1 - Rodney Graham 1. These are the closing submissions for Wai 784, a claim by Rodney Graham and others on behalf of themselves and the Kauwhata Treaty Claims Komiti and Ngā Uri Tangata o Ngāti Kauwhata ki Te Tonga (“Wai 784 Ngāti Kauwhata claim”). -

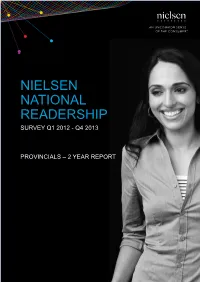

Provincial Comparatives Q1 2012

NIELSEN NATIONAL READERSHIP SURVEY Q1 2012 - Q4 2013 PROVINCIALS – 2 YEAR REPORT ANNOTATIONS Release of Nielsen Consumer and Media Insights Q1 2012 - Q4 2013 – 2 Year Report FURTHER INFORMATION: If you have any questions regarding the Nielsen Consumer and Media Insights Survey report, please contact your Account Manager or the Nielsen Media Helpdesk 0800 457 226. 2 NIELSEN NATIONAL READERSHIP Copyright © 2014 The Nielsen Company 3 PROVINCIAL TOPLINES REPORT NORTHLAND CMI CMI CMI Q1 12 - Q4 13 Q3 11 - Q2 13 Q1 11 - Q4 12 POPULATION POTENTIALS 72 72 72 (TOTAL 15+) [000s]: SAMPLE SIZE (15+): 702 706 686 DAILY NEWSPAPERS (AIR) THE NORTHERN 22 22 22 ADVOCATE 30.4% 30.6% 31.3% 10 10 11 THE NZ HERALD 13.7% 14.3% 15.0% DAILY NEWSPAPERS (WEEKLY COVERAGE) THE NORTHERN 38 41 41 ADVOCATE 52.7% 56.8% 56.9% 20 22 22 THE NZ HERALD 28.3% 31.0% 31.3% COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS (AIR) 36 38 43 THE WHANGAREI REPORT 49.9% 52.1% 59.8% 36 37 42 WHANGAREI LEADER 50.0% 51.6% 58.8% 4 NIELSEN NATIONAL READERSHIP PROVINCIAL TOPLINES REPORT TAURANGA CMI CMI CMI Q1 12 - Q4 13 Q3 11 - Q2 13 Q1 11 - Q4 12 POPULATION POTENTIALS 127 127 126 (TOTAL 15+) [000s]: SAMPLE SIZE (15+): 965 946 956 DAILY NEWSPAPERS (AIR) 39 42 43 BAY OF PLENTY TIMES 30.7% 33.4% 34.4% 21 21 23 THE NZ HERALD 16.7% 16.8% 18.1% DAILY NEWSPAPERS (WEEKLY COVERAGE) 66 70 73 BAY OF PLENTY TIMES 51.7% 54.9% 57.6% 39 41 44 THE NZ HERALD 31.1% 32.4% 34.8% COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS (AIR) 55 55 56 BAY NEWS 43.5% 43.6% 44.6% 74 76 73 THE WEEKEND SUN 58.6% 59.8% 58.1% Copyright © 2014 The Nielsen Company 5 PROVINCIAL TOPLINES -

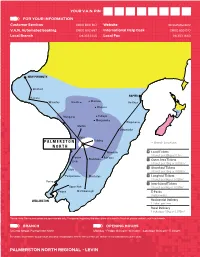

PALMERSTON NORTH REGIONAL - LEVIN Customers Can Check If an Address Is Considered Rural Or Residential by Using the ‘Address Checker’ Tool on Our Website

LOCAL SERVICES YOUR V..A NI. P N FORYOUR INFORMATION LOCAL ANDREGIONAL - SAME DAY SERVICES Customer Services Website V.A.N.Automated booking International Help Desk Local Branch 06 353 1445 Local Fax 06 353 1660 AUCKLAND NEW PLYMOUTH Stratford NAPIER Hawera Waverley Raetihi Ohakune Hastings Branch Locations Waiouru Local Tickets Wanganui Taihape 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 Mangaweka Outer Area Tickets Waipukurau 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Marton Shorthaul Tickets Dannevirke 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Longhaul Tickets Bulls Feilding 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025mP ALMERSTON3 Branch Locations Inter-Island Tickets NORTH 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Woodville Local Tickets E-Packs 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 (Nationwide-no boundaries) Foxton Pahiatua Eketahuna Outer Area Tickets Levin 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m Shorthaul Tickets Otaki 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m Paraparaumu Masterton Longhaul Tickets h 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Porirua Inter-Island Tickets Upper Hutt 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Petone Martinborough E -Packs (Nationwide) WELLINGTON Residential Delivery 1 ticket per item Rural Delivery 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.075m3 Please Note: Above zone areas are approximate only, For queries regarding the exact zone of a specific location, please contact your local branch. BRANCH OPENINGHOURS OVERNIGHT SERVICES 12 Cook Street, Palmerston North Monday - Friday: 8.00am-6.00pm Saturday: 8.00am - 11.00am Your last pick-up time is: For details on where to buy product and drop off packages, refer to the ‘Contact Us’ section of our website nzcouriers.co.nz Overnight by 9.30am to main business centres. -

Harpreet Singh

FROM GURU NANAK TO NEW ZEALAND: Mobility in the Sikh Tradition and the History of the Sikh Community in New Zealand to 1947 Harpreet Singh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, The University of Otago, 2016. Abstract Currently the research on Sikhs in New Zealand has been defined by W. H. McLeod’s Punjabis in New Zealand (published in the 1980s). The studies in this book revealed Sikh history in New Zealand through the lens of oral history by focussing on the memory of the original settlers and their descendants. However, the advancement of technology has facilitated access to digitised historical documents including newspapers and archives. This dissertation uses these extensive databases of digitised material (combined with non-digital sources) to recover an extensive, if fragmentary, history of South Asians and Sikhs in New Zealand. This dissertation seeks to reconstruct mobility within Sikhism by analysing migration to New Zealand against the backdrop of the early period of Sikh history. Covering the period of the Sikh Gurus, the eighteenth century, the period of the Sikh Kingdom and the colonial era, the research establishes a pattern of mobility leading to migration to New Zealand. The pattern is established by utilising evidence from various aspects of the Sikh faith including Sikh institutions, scripture, literature, and other historical sources of each period to show how mobility was indigenous to the Sikh tradition. It also explores the relationship of Sikhs with the British, which was integral to the absorption of Sikhs into the Empire and continuity of mobile traditions that ultimately led them to New Zealand. -

Daily Newspapers

10 The Northern Advocate (N) Daily Newspapers Whangārei Published: Morning Mon-Sat Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 1 The New Zealand Herald (N) Broadsheet Sat Auckland Published: Morning Mon-Sat 11 Bay of Plenty Times (N) Page size: Compact Mon-Fri Tauranga Broadsheet Sat Published: Morning Mon-Sat Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 2 Waikato Times (S) Broadsheet Sat Hamilton Published: Morning Mon-Sat 12 Whakātane Beacon (I) Page size: Compact Mon-Fri Whakātane Broadsheet Sat Published: Morning Wed & Fri 10 Page size: Compact 3 Taranaki Daily News (S) New Plymouth 13 Rotorua Daily Post (N) Published: Morning Mon-Sat Rotorua Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 1 Published: Morning Mon-Sat Broadsheet Sat Page size: Compact Mon-Fri Broadsheet Sat 4 Whanganui Chronicle (N) Whanganui 14 The Gisborne Herald (I) Gisborne Published: Morning Mon-Sat 2 Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 11 12 Published: Afternoon Mon-Sat Broadsheet Sat Page size: Compact 5 Manawatū Standard (S) 14 15 Wairoa Star (I) Palmerston North 13 Wairoa Published: Morning Mon-Sat Published: Morning Tues & Thu Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 15 Page size: Compact Broadsheet Sat 3 16 Hawkes Bay Today (N) 6 Wairarapa Times Age (I) 16 Hastings Masterton Published: Morning Mon-Sat Published: Morning Mon-Sat Page size: Compact Mon-Fri Page size: Compact 4 Broadsheet Sat 7 The Dominion Post (S) 5 17 The Westport News (I) Wellington Westport Published: Morning Mon-Sat Published: Afternoon Mon-Fri Page size: Compact Mon-Fri 6 Page size: Broadsheet Broadsheet Sat 18 Greymouth Star (I) 8 The Nelson Mail (S) 7 Greymouth -

Appendix 1 – Heritage Places

APPENDIX 1 – HERITAGE PLACES APPENDIX 1A – WETLANDS, LAKES, RIVERS AND THEIR MARGINS .................................................. 1 Heritage Places Heritage – APPENDIX 1B – SIGNIFICANT AREAS OF INDIGENOUS FOREST/VEGETATION (EXCLUDING RESERVES) .................................................................................................................................................... 3 APPENDIX 1C – OUTSTANDING NATURAL FEATURES ..................................................................... 5 Appendix 1 Appendix APPENDIX 1D – TREES WITH HERITAGE VALUE .............................................................................. 6 APPENDIX 1E – BUILDINGS AND OBJECTS WITH HERITAGE VALUE .................................................. 7 COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS ................................................................................................................................. 7 OTHER TOWNSHIPS ........................................................................................................................................... 7 HOUSES.............................................................................................................................................................. 8 RURAL HOUSES AND BUILDINGS ....................................................................................................................... 9 OBJECTS AND MEMORIALS.............................................................................................................................. 10 MARAE BUILDINGS -

Environmental Scan

Environmental Scan March 2020 www.mdc.govt.nz Environmental Scan 2020 1 Contents INTRODUCTION 5 SOCIAL AND CULTURAL PROFILE 11 ECONOMIC PROFILE 21 ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE 31 MAJOR REGIONAL DEVELOPMENTS/PROJECTS 37 GOVERNMENT PROPOSALS, LEGISLATION, 39 INQUIRIES AND NATIONAL TRENDS BIBLIOGRAPHY 60 2 Environmental Scan 2020 Environmental Scan 2020 3 Introduction An Environmental Scan looks at what changes are likely to affect the future internal and external operating environment for Manawatū District Council (Council). It looks at where the community is heading and what we, as Council, should be doing about it. It should lead to a discussion with elected members about what tools Council has available to influence the direction the community is taking. The purpose of local government, as set out in the Local Government Act 2002 includes reference to the role of local authorities in promoting the social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing of their communities. The indicators included in this report have been grouped into each of the wellbeings under the headings of “Social and Cultural Profile,” “Economic Profile” and “Environmental Profile.” However, it is recognised that the many of these indicators have impacts across multiple wellbeings. Council has used the most up-to-date data available to prepare this Environmental Scan. In some cases this data is historic trend data, sometimes it is current at the time the Environmental Scan was finalised, and in some cases Council has used data and trends to prepare future forecasts. Council does not intend to update the Environmental Scan over time, but the forecasting assumptions contained within Council’s Ten Year Plan will be continually updated up until adoption.