The Changing Public Image of Smoking in the United States: 1964–2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brands MSA Manufacturers Dateadded 1839 Blue 100'S Box

Brands MSA Manufacturers DateAdded 1839 Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6 oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Silver Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 Amsterdam Shag 35g Pouch or 150g Tin Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S 7/1/2021 Bali Shag RYO gold or navy pouch or canister Top Tobacco L.P. -

American Snuff Co., Memphis: the Business of Being Sustainable

[ e American Snuff Co., Memphis: The Business of Being Sustainable American Snuff Company, an indirect subsidiary of Reynolds American Inc. (NYSE: RAI), is the nation’s second largest manufacturer of smokeless tobacco products, with Grizzly and • Established 1904 Kodiak leading the way. Closing in on a 90% diversion rate to the landfill, American Snuff Company of Memphis fully embraces the • Employs over 200 concept of a circula r economy; new ground for most industries in the United States. • Close to achieving “We realize the closer we come to being a zero-waste company, Zero Waste status the more effort and commitment it will take,” said Jaimie Bright, Lead Manager of the Environmental Health and Safety group with • Member since 2014 American Snuff. In recent years, American Snuff Company of Memphis has become one of the most sustainable industries in Tennessee. For American Snuff, this commitment to a sustainable business model presents a welcome challenge. Most companies accept that production waste is a part of business, and while most try to minimize the waste or find an outlet for it, not many will go the distance, literally, like American Snuff. “We had almost 20 tons of tobacco production waste a month that we had no real sustainable outlet for,” said Quincey Young, Senior Scientist at American Snuff, “but we were determined to find the most beneficial re-use we could.” TGSP Highlights- February 2017 Tobacco waste, as it turns out, is an excellent source of nitrogen which makes it a welcome addition to compost production. The nearest compost facility capable of using that much tobacco was The Compost Company LLC, in Ashland City, just over 200 miles away. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Batus Holdings Inc, Организовано У Складу Са Правом Сједињених Америчких Држава , Са Седиштем На Адреси 2711 Centerville Rd

Република Србија КОМИСИЈА ЗА ЗАШТИТУ КОНКУРЕНЦИЈЕ Број : 6/0-02-180/2017-8 Датум : 03. март 2017. године Б е о г р а д Председник Комисије за заштиту конкуренције , на основу члана 37. став 2. Закона о заштити конкуренције („ Службени гласник РС “, број 51/09 и 95/13), члана 192. став 1. Закона о општем управном поступку („ Службени лист СРЈ ", бр . 33/97, 31/01 и „ Службени гласник РС “, бр . 30/10) и члана 2. став 1. тачка 6. Тарифника о висини накнада за послове из надлежности Комисије за заштиту конкуренције („ Службени гласник РС “, број 49/11), одлучујући по пријави концентрације број 6/0- 02-180/2017-8, коју је дана 31. јануара 2017. године поднело привредно друштво Batus Holdings Inc, организовано у складу са правом Сједињених Америчких Држава , са седиштем на адреси 2711 Centerville Rd. Suite 400, Vilmington, Delaver, SAD, 19808, регистровано при Заводу за корпорације Delaver State Department под бројем 0851178, преко пуномоћника адвокат a Тијане Којовић из Адвокатског ортачког друштва БДК Адвокати , Београд , Мајке Јевросиме бр . 23, дана 03. марта 2017. године , доноси следеће Р Е Ш Е Њ Е 1 I ОДОБРАВА СЕ у скраћеном поступку концентрација учесника на тржишту која настаје стицањем непосредне појединачне контроле од стране друштва , Batus Holdings Inc, организовано у складу са правом Сједињених Америчких Држава , са седиштем на адреси 2711 Centerville Rd. Suite 400, Vilmington, Delaver, SAD, 19808, регистровано при Заводу за корпорације Delaver State Department под бројем 0851178, над друштвом Reynolds American Inc, организованим у складу са правом Сједињених Америчких Држава , са седиштем на адреси 327 Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, Severna Karolina 27603- 1725, регистрованим код Државног Секретара Северне Каролине под регистарским бројем 0705047, до које долази на основу уговорног преузимања већинског удела у капиталу Reynolds American Inc, као Циљном друштву . -

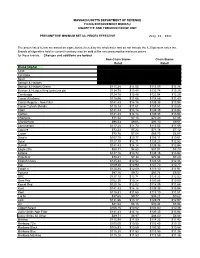

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Warnings for Chewing Tobacco Products

COMMENTS ON PETITION OF R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY AND AMERICAN SNUFF COMPANY FOR RULEMAKING TO ADJUST STATUTORY SMOKELESS TOBACCO WARNING DOCKET NO. FDA-2011-P-0573 November 9, 2012 The undersigned organizations submit these comments on the Petition of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (“RJR”) and the American Snuff Company (“ASC”), Reynolds American, Inc.’s smokeless tobacco subsidiary, requesting the Commissioner of Food and Drugs to initiate a rulemaking proceeding to alter the text of the statutorily-required smokeless tobacco (“ST”) product warning statement. The undersigned urge that the Petition be denied by the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). Though presented as merely a request to FDA to modify one of the statutory product warnings on smokeless tobacco, in reality the RJR Petition is a transparent attempt to secure FDA’s support for their marketing of ST as a safer product than cigarettes, while evading the evidentiary requirements that Congress carefully constructed to ensure that such claims of reduced harm do not serve to increase tobacco use, cause more people to become addicted to tobacco, and die from tobacco-related disease. The Petition thus represents an attack on the integrity of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (“Tobacco Control Act”), the statute FDA is charged with enforcing, and should be treated as such. The Petition is part and parcel of a broader industry campaign to circumvent the requirements of Section 911 of the Tobacco Control Act in order to promote ST as a “harm reducing” product, led by the 1 two largest cigarette manufacturers – RJR and Philip Morris USA – who have entered the ST market and have every incentive to both expand the use of ST and to ensure that ST functions to protect and expand the market for cigarettes. -

RAI Board Member Daly Resigns; Jerome Abelman Designated to Succeed Him

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Contact: Investor Relations: Media: RAI 2016-03 Morris Moore Jane Seccombe (336) 741-3116 (336) 741-5068 RAI board member Daly resigns; Jerome Abelman designated to succeed him WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Jan. 15, 2016 – Reynolds American Inc. (NYSE: RAI) announced today that John P. Daly has resigned as a member of RAI’s board of directors, effective Feb. 4. Daly has served on RAI’s board since December 2010, one of five board members designated by Brown & Williamson Holdings, Inc. (B&W), a subsidiary of British American Tobacco p.l.c. (BAT), under the terms of the 2004 governance agreement, as amended, between RAI, B&W and BAT. His three-year term as a Class II director was scheduled to expire in 2018. Daly, former chief operating officer at BAT, retired from BAT in 2014. Jerome Abelman, director of legal and external affairs, and general counsel at BAT, has been designated by BAT for nomination to RAI’s board to succeed Daly, effective Feb. 4. RAI’s board will vote on Abelman’s formal nomination at its regularly scheduled Feb. 4 meeting. “John has given us outstanding business advice and counsel to the benefit of RAI and its shareholders, and we wish him the very best in retirement,” said Thomas C. Wajnert, chairman of RAI’s board. Abelman has been with the BAT Group for 13 years and has held a number of legal, corporate and regulatory roles. He joined BAT’s management board as director, corporate and regulatory affairs, in January 2015, and was appointed director, legal and external affairs, and general counsel in May 2015. -

Vintage Cigarette Ad Exhibit Focuses on Industry Manipulation He Kindly Looking Doctor in 1920 to 1954

& ■ A monthly section on physical and mental well-being. April 11, 2007 SECTION 2 A LSO INSIDE C ALENDAR 30 |C LASSIFIEDS 39 Era of by D Sue Dremann Photo by Marjan Sadoughi Dr. Robert Jackler poses in front of a display of ads featuring doctors purportedly promoting cigarettes. Vintage cigarette ad exhibit focuses on industry manipulation he kindly looking doctor in 1920 to 1954. and political winds of the times. a white lab coat holds up The exhibit sheds light on The golden age of cigarette ads Ta package of Lucky Strike tobacco company tactics by show- ended in 1954, when the Federal cigarettes, gazing at them fondly. ing how orchestrated campaigns Trade Commission clamped “20,679 Physicians say ‘Luck- have worked over time. The down on tobacco companies ies are less irritating.’ Your Jacklers and Robert Proctor, a making health claims. Throat Protection against irri- Stanford professor of history and Tobacco was a known cause of tation, against cough,” the col- science, are writing a book featur- oral cancer as early as the 18th orful ad proclaims. ing many of the vintage ads. century, but the link to lung Dr. Robert Jackler, professor The exhibition has poignancy cancer wasn’t accepted until the and chair of otolaryngology at for Dr. Jackler, whose mother, early 1940s and ‘50s, Dr. Jack- Stanford, was struck by the ad’s a long-term smoker, was diag- ler said. When physician Isaac audacious misuse of the physi- nosed with lung cancer shortly Adler made the connection in cian’s iconic image of authority. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Case M1287J Proposed Acquisition of Reynolds American Inc by British

Case M1287J Proposed Acquisition of Reynolds American Inc by British American Tobacco Plc, Batus Holdings Inc, and Flight Acquisition Corporation ______________ _____________ Decision Document No: CICRA 17/07 Date: 10 April 2017 Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority 2nd Floor Salisbury House, 1-9 Union Street, St Helier, Jersey, JE2 3RF Tel 01534 514990, Fax 01534 514991 Web: www.cicra.je Summary 1. This Decision concerns the proposed acquisition by British American Tobacco PLC (BAT), Batus Holdings Inc (BATUS) and Flight Acquisition Corporation (FAC) of Reynolds American Inc (RAI). The transaction has been notified to the Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority (JCRA) for approval pursuant to Article 21 of the Competition (Jersey) Law 2005 (the Law). 2. The JCRA has determined that the proposed acquisition will not lead to a substantial lessening of competition in any relevant market in Jersey and hereby approves the acquisition. The Notified Transaction 3. On 15 March 2017 the JCRA received an application for approval from BAT, BATUS and FAC (the Purchasers) for their proposed acquisition of RAI (the Target). 4. As a result of the transaction, BATUS will acquire 58% of the share capital in RAI, and therefore acquire direct sole control. [] Accordingly, after the merger, BATUS will own 100% of RAI’s share capital, either directly or through wholly owned subsidiaries. 5. The JCRA registered the application on its website on 15 March, with a deadline for comments of 29 March. No submissions were received. The Parties 6. The Target is -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

First-Of-Its-Kind Filing for VUSE Products

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Media Contact: Kaelan Hollon [email protected] 202-421-4921 VUSE Premarket Tobacco Product Application Filed for Substantive Review by the FDA First-of-its-Kind Filing for VUSE Products WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Nov. 27, 2019 – Today, Reynolds American Inc. (“RAI”) announced that the recently-submitted Premarket Tobacco Product Application (“PMTA”) for VUSE vapor products has been filed by the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) for substantive scientific review, moving the application one step further through the review process. “This is a first-of-its-kind application for VUSE products, and it puts VUSE one step closer to gaining a marketing order from the FDA. FDA will now review our scientific justification and determine the appropriateness of VUSE e-cigarette products against the public health standard,” notes RAI CEO Ricardo Oberlander. “For adult tobacco consumers seeking an alternative source of nicotine, having FDA oversight of e-cigarette products is an important step to ensure those alternatives meet strict regulatory scrutiny.” The FDA’s scientific review of the VUSE application – which totals more than 150,000 pages of research and data – comes just over six weeks after its initial submission to the FDA. The FDA, per its earlier-issued guidance, considers the following issues, among others: • Risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including both users and nonusers of tobacco products; • Whether people who currently use any tobacco product would be more or less likely to stop using such products if the proposed new tobacco product were available; • Whether people who currently do not use any tobacco products would be more or less likely to begin using tobacco products if the new product were available; and • The methods, facilities, and controls used to manufacture, process, and pack the new tobacco product.