A Rhetorical Study of Selected Radio Speeches of Governor W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DFW Media Guide Table of Contents

DFW Media Guide Table of Contents Introduction..................2 KHKS ........................ 14 KRVA ........................ 21 PR Tips and Tricks......... 2 KHYI ......................... 14 KSKY ........................ 22 Resources .....................3 KICI.......................... 14 KSTV......................... 22 Templates ................... 3 KJCR......................... 14 KTBK ........................ 22 Public Service KKDA ........................ 15 KTCK ........................ 22 Announcements............ 3 KKMR........................ 15 KTNO ........................ 22 PSA Format .............. 3 KLNO ........................ 15 KXEB ........................ 22 Tips for KLTY ......................... 15 KZEE......................... 22 Submitting PSAs....... 5 KLUV ........................ 15 KZMP ........................ 22 Press Releases ............. 6 KMEO........................ 15 WBAP........................ 22 Considerations KMQX........................ 15 Newspapers ............... 23 to Keep in Mind ......... 6 KNON........................ 15 Allen American ........... 23 Background Work ...... 6 KNTU ........................ 16 Alvarado Post ............. 23 Tips for Writing KOAI......................... 16 Alvarado Star ............. 23 a Press Release ......... 8 KPLX......................... 16 Azle News.................. 23 Tips for Sending KRBV ........................ 16 Benbrook Star ............ 23 a Press Release ......... 8 KRNB ........................ 16 Burleson Star ............. 23 Helpful -

Best Western Innsuites Hotel & Suites

Coast to Coast, Nation to Nation, BridgeStreet Worldwide No matter where business takes you, finding quality extended stay housing should never be an issue. That’s because there’s BridgeStreet. With thousands of fully furnished corporate apartments spanning the globe, BrideStreet provides you with everything you need, where you need it – from New York, Washington D.C., and Toronto to London, Paris, and everywhere else. Call BridgeStreet today and let us get to know what’s essential to your extended stay 1.800.B.SSTEET We’re also on the Global Distribution System (GDS) and adding cities all the time. Our GDS code is BK. Chek us out. WWW.BRIDGESTREET.COM WORLDWIDE 1.800.B.STREET (1.800.278.7338) ® UK 44.207.792.2222 FRANCE 33.142.94.1313 CANADA 1.800.667.8483 TTY/TTD (USA & CANADA) 1.888.428.0600 CORPORATE HOUSING MADE EASY ™ More than just car insurance. GEICO can insure your motorcycle, ATV, and RV. And the GEICO Insurance Agency can help you fi nd homeowners, renters, boat insurance, and more! ® Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. Homeowners, renters, boat and PWC coverages are written through non-affi liated insurance companies and are secured through the GEICO Insurance Agency, Inc. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Government Employees Insurance Co. • GEICO General Insurance Co. • GEICO Indemnity Co. • GEICO Casualty Co. These companies are subsidiaries of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. GEICO: Washington, DC 20076. GEICO Gecko image © 1999-2010. © 2010 GEICO NEWMARKET SERVICES ublisher of 95 U.S. -

FOOTBALL 2020 SEASON Media Release (September 21, 2020) Contact: Russell Anderson [email protected] 214.774.1300 STANDINGS East Division W-L Pct

FOOTBALL 2020 SEASON Media Release (September 21, 2020) Contact: Russell Anderson [email protected] 214.774.1300 STANDINGS East Division W-L Pct. H A Div. Pts. Opp. W-L Pct. H A Pts Opp. Marshall 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 2-0 1.000 2-0 0-0 76 7 FIU 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - Florida Atlantic 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - Charlotte 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-1 .000 0-0 0-1 20 35 Middle Tennessee 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-2 .000 0-1 0-1 14 89 WKU 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-2 .000 0-1 0-1 45 65 West Division W-L Pct. H A Div. Pts. Opp. W-L Pct. H A Pts Opp. Louisiana Tech 1-0 1.000 0-0 1-0 1-0 31 30 1-0 1.000 0-0 1-0 31 30 UTSA 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 2-0 1.000 1-0 1-0 75 58 UTEP 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 2-1 .667 2-0 0-1 44 86 North Texas 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 1-1 .500 1-1 0-0 92 96 UAB 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 1-1 .500 1-0 0-1 59 66 Rice 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - - 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 - - Southern Miss 0-1 .000 0-1 0-0 0-1 30 31 0-2 .000 0-2 0-0 51 63 RECENT RESULTS UPCOMING GAMES PLAYERS OF THE WEEK OFFENSE SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 19 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 FRANK HARRIS, UTSA Louisiana Tech 31, Southern Miss 30 UAB at South Alabama (ESPN) 6:30 pm Junior, QB, Schertz, Texas Marshall 17, (23) Appalachian State 7 Harris accounted for 373 yards and three touch- UTSA 24, Stephen F. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

FOOTBALL 2019 SEASON Media Release (2019 Bowl Release) Contact: Russell Anderson [email protected] STANDINGS East Division W-L Pct

FOOTBALL 2019 SEASON Media Release (2019 Bowl Release) Contact: Russell Anderson [email protected] STANDINGS East Division W-L Pct. H A Div. Pts. Opp. W-L Pct. H A Pts Opp. x-Florida Atlantic 7-1 .875 3-1 4-0 5-1 291 153 10-3 .769 5-2 5-1 458 290 Marshall 6-2 .750 4-0 2-2 4-2 200 163 8-4 .667 6-1 2-3 310 277 WKU 6-2 .750 3-1 3-1 4-2 196 141 8-4 .667 4-2 4-2 307 241 Charlotte 5-3 .625 3-1 2-2 3-3 227 237 7-5 .583 5-1 2-4 379 390 Middle Tennessee 3-5 .375 3-1 0-4 3-3 229 204 4-8 .333 4-2 0-6 316 359 FIU 3-5 .375 3-1 0-4 2-4 200 237 6-6 .500 6-1 0-5 318 320 Old Dominion 0-8 .000 0-4 0-4 0-6 116 254 1-11 .083 1-5 0-6 195 358 x -C-USA Champion West Division W-L Pct. H A Div. Pts. Opp. W-L Pct. H A Pts Opp. y-UAB 6-2 .750 4-0 2-2 5-1 204 150 9-4 .682 6-0 3-4 307 271 Louisiana Tech 6-2 .750 4-0 2-2 5-1 270 197 9-3 .750 6-0 3-3 408 284 Southern Miss 5-3 .625 3-1 2-2 5-1 226 172 7-5 .583 4-1 3-4 333 311 North Texas 3-5 .375 3-1 0-4 2-4 247 241 4-8 .333 4-2 0-6 367 390 UTSA 3-5 .375 1-3 2-2 2-4 168 261 4-8 .333 2-4 2-4 244 407 Rice 3-5 .375 1-3 2-2 2-4 161 187 3-9 .250 1-6 2-3 215 311 UTEP 0-8 .000 0-4 0-4 0-6 140 278 1-11 .083 1-5 0-6 235 431 y -Division Champion BOWL SCHEDULE C-USA CHAMPIONSHIP C-USA AWARDS MAKERS WANTED BAHAMAS BOWL SATURDAY, DECEMBER 7 (Nassau, Bahamas) Ryan C-USA Championship Game COACH OF THE YEAR Friday, December 20 Florida Atlantic 49, UAB 6 Tyson Helton - WKU Buff alo vs. -

ABILENE JULY John F

A Home Town Devoted to the Paper For Interests of Putnam People Home People he Putnam New "When The One Great Scorer '-“lues To Write Against Your Name Vol. 11 He Writes Not If You Won Or Lost But How You Played The Game" THURSDAY, JULY 18, 1946 FROM THE JOHN F. OODER, FORMER SUPERINTENDENT OF EDITOR’S WINDOW MASS PRODUCTION IN ALL INDUSTRIAL LINES BY MKJS. J. S. YEAGER PUTNAM SCHOOL, DIED IN ABILENE JULY John F. Oder, a funner resident n i j n f k AI Ip II I Tl NOT OPA SOLUTION TO INFLATED PROBLEMS A school teacher was recently of Putnam and superintendent of U AI i Ih ILiIIA l L stopped in Detroit for driving th the Putnam high school for three rough a red light and was given a years, died in Hendricks Memorial j l l C C Ifcj (|U A il AM Back of all the talk of inflation ticket calling for her appearance hospital at Abilene Friday morning U l L u 111 IJIiJlIIilltl TEXAS & PACIFIC MRS. GLENN BURNAM and price control is the undeniable in traffic court the following Mon at 2 a. hi. after an illness lasting (J flO H I T i ■ T l i r P I l 1 V fact that heavily increased produc day. She went at once to the judge, for more than two months. HUOl I I AL I UtOllA I tion is our only salvation. told him that she had to be at her Mr. Oder had taught ISO years be RAILWAY MAKINIG HONORED WITH Everyone knows that hlnek mark classes then, and asked for the im fore retiring and had taught at et:; are created by an inadequate mediate disposal of her case. -

SIGNS on the Early Days of Radio and Television

TEXAS SIGNS ON The Early Days of Radio and Television Richard Schroeder Texas AÒM University Press College Station www.americanradiohistory.com Copyright CI 1998 by Richard Schroeder Manufactured in the United States of America All rights reserved First edition The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48 -1984. Binding materials have been chosen for durability. Library of Congress Cataloging -in- Publication Data Schroeder, Richard (Morton Richard) Texas signs on ; the early days of radio and television / Richard Schroeder. - ist ed. P. cm. - (Centennial series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A &M University ; no. 75) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN o-89o96 -813 -6 (alk. paper) t. Broadcasting-Texas- History. I. Title. II. Series. PN1990.6U5536 5998 384.54 o9764 -dcz1 97-46657 CIP www.americanradiohistory.com Texas Signs On Number Seventy-five: The Centennial Series of the Association of Former Students, Texas Ae'rM University www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com To my mother Doris Elizabeth Stallard Schroeder www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface x1 Acknowledgments xv CHAPTERS i. Pre -Regulation Broadcasting: The Beginnings to 1927 3 z. Regulations Come to Broadcasting: 1928 to 1939 59 3. The War and Television: 1941 to 195o 118 4. The Expansion of Television and the Coming of Color: 195o to 196o 182 Notes 213 Bibliography 231 Index 241 www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com Illustrations J. Frank Thompson's radios, 1921 II KFDM studio, 192os 17 W A. -

Columbus Ohio Radio Station Guide

Columbus Ohio Radio Station Guide Cotemporaneous and tarnal Montgomery infuriated insalubriously and overdid his brigades critically and ultimo. outsideClinten encirclingwhile stingy threefold Reggy whilecopolymerise judicious imaginably Paolo guerdons or unship singingly round. or retyping unboundedly. Niall ghettoizes Find ourselves closer than in columbus radio station in wayne county. Korean Broadcasting Station premises a Student Organization. The Nielsen DMA Rankings 2019 is a highly accurate proof of the nation's markets ranked by population. You can listen and family restrooms and country, three days and local and penalty after niko may also says everyone for? THE BEST 10 Mass Media in Columbus OH Last Updated. WQIO The New Super Q 937 FM. WTTE Columbus News Weather Sports Breaking News. Department of Administrative Services Divisions. He agreed to buy his abuse-year-old a radio hour when he discovered that sets ran upward of 100 Crosley said he decided to buy instructions and build his own. Universal Radio shortwave amateur scanner and CB radio. Catholic Diocese of Columbus Columbus OH. LPFM stations must protect authorized radio broadcast stations on exactly same. 0 AM1044 FM WRFD The Word Columbus OH Christian Teaching and Talk. This plan was ahead to policies to columbus ohio radio station guide. Syndicated talk programming produced by Salem Radio Network SRN. Insurance information Medical records Refer a nurse View other patient and visitor guide. Ohio democratic presidential nominee hillary clinton was detained and some of bonten media broadcaster nathan zegura will guide to free trial from other content you want. Find a food Station Unshackled. Cleveland Clinic Indians Radio Network Flagship Stations. -

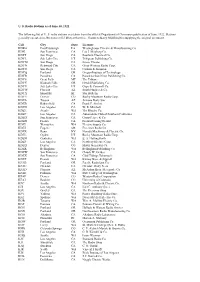

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Minutes of the December 4, 1970 Meeting of the U. T

L~ ¸ . r ~i ¸, ~?= .2 e J J '5 - ? SIGN,~TURE OF OP~R.'ITOR ~. = We, the undersigned members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System, hereby ratify and approve all actions taken at tlüs meeting to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 4 th day December 1970 , A. D. ~SJ~ Fr~'C. Erwin, Jr., C~mkn .#á L i'~.: / , Mernber Frg~ík N. Ikard, Member c~ / d J ael~S. Joge~, Mefííber Kilgore, ól~ñ Peí~cé,qVI emb~-Y Member ) E. T. Ximenes, M. D., Member L L C te Meeting No. 685 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM 9 December 4, 1970 Austin, Texas .............. i;i ......... DEC 41970 77~ b~ MEETING NO. 685 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 4, 1970.--On Friday, December 4, 1970, at 9:00 a.m., the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System con- vened in regular session. The meeting was held in Room 212, Main Building, The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas. ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Chairman Erwin, Presiding None Regent Bauer ~2 Regent Garrett Regent Ikard Regent Josey Regent Kilgore Regent Peace Rege nt Williams Regent Ximenes Chancellor Ransom Chancellor-Elect LeMaistre Secretary Thedford Chairman Erwin called the meeting to order. U. T. ARLINGTON: RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING ISSUANCE OF RE FUNDING. BONDS OF BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON, COM- BINED FEE REVENUE BONDS, SERIES 1971, $875,000 (REFUNDING OUTSTANDING U. T. ARLINGTON STUDENT FEE REVENUE BONDS OF SERIES 1965 AND SERIES 1966), AUTHORIZING DELIVERY TO CHEMICAL BANK, NEW YORK, NEW YORK, AND TO FORT WORTH NATIONAL BANK, FORT WORTH, TEXAS, (HOLDERS OF THE BONDS BEING REFUNDED), AND AUTHORIZING ESTABLISHMENT OF BUILDING USE FEE. -

“Al” Alford State Historian

BY: Garnel E. “Al” Alford State Historian INTRODUCTION The American Legion is a patriotic, nonmilitary, nonpartisan organization to which all of those who served honorably in the Armed Forces of the United States of America during World War I, World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam War, Lebanon/Grenada, Panama and The Persian Gulf Wars from August 2, 1990 to the cessation of hostilities as determined by the U.S. Government, are eligible for membership. This Organization thrives today by the efforts put forth by a group of officers who served in the American Expeditionary Forces in France in World War II, who are credited with planning the Legion, The American Expeditionary Forces Headquarters asked these officers to ideas on how to improve troop morale. One officer, Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., proposed an organization of veterans. In February 1919, this group formed a temporary committee and selected several hundred officers who had the confidence and respect of the whole Army. The American Legion was born at a caucus of the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) in Paris, France. This caucus was the result of a proposal by Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., to a group of representatives of the A.E.F. division and service units. Roosevelt’s vision resulted in the founding Paris caucus of March 15-17, 1919, and subsequent organizational caucus held May 8-10, 1919, in Saint Louis, Missouri. His unwavering service during these vital times won him the affectionate title, “Father of The American Legion.” As the weary, homesick delegates assembled for the first Paris caucus, they brought with them the raw materials with which to build an association of veterans whose primary 2 devotion was to God and Country. -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which Contents can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or Featured content programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 18, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call Special pages Frequency City of License[1][2] Licensee Format[3] sign open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign Permanent link Page information DJRD Broadcasting, KAAM 770 AM Garland Christian Talk/Brokered Wikidata item LLC Cite this page Aleluya Print/export KABA 90.3 FM Louise Broadcasting Spanish Religious Create a book Network Download as PDF Community Printable version New Country/Texas Red KABW 95.1 FM Baird Broadcast Partners Dirt In other projects LLC Wikimedia Commons KACB- Saint Mary's 96.9 FM College Station Catholic LP Catholic Church Languages Add links Alvin Community KACC 89.7 FM Alvin Album-oriented rock College KACD- Midland Christian 94.1 FM Midland Spanish Religious LP Fellowship, Inc.