Wellington Street Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woolwich to Falconwood

Capital Ring section 1 page 1 CAPITAL RING Section 1 of 15 Woolwich to Falconwood Section start: Woolwich foot tunnel Nearest station to start: Woolwich Arsenal (DLR or Rail) Section finish: Falconwood Nearest station to finish: Falconwood (Rail) Section distance 6.2 miles plus 1.0 miles of station links Total = 7.2 miles (11.6 km) Introduction This is one of the longer and most attractive sections of the Capital Ring. It has great contrasts, rising from the River Thames to Oxleas Meadow, one of the highest points in inner London. The route is mainly level but there are some steep slopes and three long flights of steps, two of which have sign-posted detours. There is a mixture of surfaced paths, a little pavement, rough grass, and un-surfaced tracks. There are many bus stops along the way, so you can break your walk. Did you know? With many branches and There are six cafés along the route. Where the walk leaves the Thames loops, the Green Chain there are two cafés to your right in Thames-side Studios. The Thames walk stretches from the River Thames to Barrier boasts the 'View café, whilst in Charlton Park you find the 'Old Nunhead Cemetery, Cottage' café to your right when facing Charlton House. Severndroog spanning fields, parks and woodlands. As Castle has a Tea Room on the ground floor and the latter part of the walk indicated on the maps, offers the Oxleas Wood café with its fine hilltop views. much of this section of the Capital Ring follows some of the branches of The route is partially shared with the Thames Path and considerably with the Green Chain. -

Queen Elizabeth Hospital SE18 4QH Common and Park Do These Walks to Help Meet Your Daily Walking Target and Improve Your Wellbeing

Wellbeing at Work Queen Elizabeth Hospital SE18 4QH Common and Park Do these walks to help meet your daily walking target and improve your wellbeing LOCAL AREA The Queen Elizabeth Hospital is almost entirely surrounded by green space, though much of it is closed to the public (Ministry of Defence establishments) or fenced off (a cemetery and a sports ground just to the West of the hospital). However, Woolwich Common faces the main entrance and the varied Horn Fair Park is tucked away very close. Charlton Park and Mary Wilson Parks are also not far away. There are good opportunities for enjoyable lunchtime and after-work walks. In fact two of London’s great long distance walking routes, the Green Chain and the Capital Ring pass close to the Queen Elizabeth and you can have a taster on our walk. DESCRIPTION A pleasant walk around Woolwich Common and a visit to the varied Horn Fair Park with its sunken rose garden. The walk shares two short sections with both the Green Chain and the Capital Ring. Those seeking a shorter walk can choose to do either the Common or the Horn Fair Park halves of the walk, instead of both. The May trees are splendid on the Common in Spring, as are the roses in Horn Fair Park in June. Wear sensible footwear and choose a dry day for a walk on the Common. TOTAL DISTANCE 2.1 miles TIME 40 minutes PACES 4200 paces An alternative shorter route is offered (1.4 miles/26 minutes/2750 paces). Wellbeing at Work Queen Elizabeth Hospital SE18 4QH Common and Park 1 Start at the main entrance to Queen 3 Continue on for several hundred metres as the path swings Elizabeth Hospital: around to the right. -

Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route

Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route Woolwich Common Estate MUGA Address: Woolwich Common Estate MUGA, Woolwich, London SE18 4DB Transport: Woolwich Arsenal - South Eastern & DLR; 18-minute walk from Woolwich Arsenal Station Buses 122 and 469 take you to Nightingale Place and then a 5- minute walk from there Access: This site has a ramp for access. Our volunteers will be available near the station and site for support. For more information: Visit www.tfl.gov.uk to plan your journey to Woolwich Arsenal station. Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route Directions from Woolwich Arsenal Station Exit Woolwich arsenal station. A ramp is available to the left. Next, turn left onto Woolwich New Road Walk towards Tesco Extra Keep Tesco Extra to your right. Next at the fork, keep left on to Woolwich New Road. At the junction, continue straight, along the left side pavement. Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route When you reach this junction, use the pedestrian crossing and cross to the other side of the road. Turn left onto Nightingale Place. Very soon you will see a bus stop on the other side of the road and on your left there is a path going between the buildings Walk down this path in between the buildings Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route The MUGA will be on your right. Directions from Bus Stop J, Nightingale Place Get off the bus at Stop G, Nightingale Place and turn left. At this junction follow the pavement round to the right onto Nightingale Place and keep straight. Woolwich Common Estate MUGA - Photo Route Very soon you will see a bus stop on the other side of the road and on your left there is a path going between the buildings Walk down this path in between the buildings The MUGA will be on your right. -

Charlie Davis Spencer Drury

A better cycle Charlie Davis & Spencer Drury Charlie Davis route through Working hard for Eltham Spencer Drury Eltham Cleaning the Eltham sign Reporting back to Eltham Controversial road changes on In February, Charlie and Spencer asked Well Hall Road installed despite questions about the cleanliness of Eltham alternative proposals High Street. Charlie’s focus on cleaning the marble Eltham sign at the western end of the Keeping Greenwich High Street led to a commitment to clean the whole area properly three times a year. Council focused on Eltham Dear Resident, Parking Zone changes delayed We were grateful for all the help we After a year as your Councillors, we (Charlie and received to get re-elected a year ago. Spencer has kept up the pressure on the Spencer) wanted to report back to you what we had been Council over changing parking zones to reflect doing as your representatives in the Town Hall at residents’ wishes around Strongbow & Eltham Woolwich. Charlie and Spencer on the newly Park Gardens. Despite promising changes installed (&damaged) traffic island. last summer, the Council seems to be It has been a busy year with a new Council Leader who incapable of making the promised alterations. has bought a new style to the role (with more selfies than any other London Leader as one blogger claims). From In September 2018, unanimously agreed that our point of view our first year has bought some success Charlie and Spencer the Council should look at for Eltham: asked for the Council to alternative routes, in review its decision to particular along Glenlea New hotel for Orangery? ■ The return of Town Wardens to our High Street change the road layout at Road as an existing cycle which Eltham’s police suggested would free them up the junction of Well Hall path ran through Eltham In Dec 2018, Charlie pushed for the Council’s to spend more time patrolling residential areas where Road and Dunvegan Station. -

Land at Love Lane, Woolwich

Simon Fowler Avison Young – UK By email only Our Ref: APP/E5330/W/19/3233519 Date: 30 July 2020 Dear Sir CORRECTION NOTICE UNDER SECTION 57 OF THE PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 Land at Love Lane, Grand Depot Road, John Wilson Street, Thomas Street, and Woolwich New Road, Woolwich SE18 6SJ for 1. A request for a correction has been received from Winckworth Sherwood on behalf of the Appellant’s in respect of the Secretary of State’s decision letter on the above case dated 3 June 2020. This request was made before the end of the relevant period for making such corrections under section 56 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 (the Act), and a decision has been made by the Secretary of State to correct the error. 2. There is a clear typographical error in the IR, specifically at IR12.18 where there is an incorrect reference to Phase 4 when the intention was to refer to Phase 3. The correction relates to this reference only and is reflected in the revised Inspector’s report attached to this letter. 3. Under the provisions of section 58(1) of the Act, the effect of the correction referred to above is that the original decision is taken not to have been made. The decision date for this appeal is the date of this notice, and an application may be made to the High Court within six weeks from the day after the date of this notice for leave to bring a statutory review under section 288 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. -

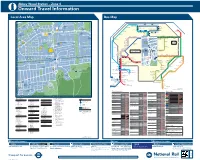

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

Abbey Wood Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 45 1 HARTSLOCK DRIVE TICKFORD CLOSE Y 1 GROVEBURY ROAD OAD 16 A ALK 25 River Thames 59 W AMPLEFORTH R AMPLEFORTH ROAD 16 Southmere Central Way S T. K A Crossway R 1 B I N S E Y W STANBROOK ROAD TAVY BRIDGE Linton Mead Primary School Hoveton Road O Village A B B E Y W 12 Footbridge T H E R I N E S N SEACOURT ROAD M E R E R O A D M I C H A E L’ S CLOSE A S T. AY ST. MARTINS CLOSE 1 127 SEWELL ROAD 1 15 Abbey 177 229 401 B11 MOUNTJOYCLOSE M Southmere Wood Park ROAD Steps Pumping GrGroroovoveburyryy RRoaadd Willow Bank Thamesmead Primary School Crossway Station W 1 Town Centre River Thames PANFIE 15 Central Way ANDW Nickelby Close 165 ST. HELENS ROAD CLO 113 O 99 18 Watersmeet Place 51 S ELL D R I V E Bentham Road E GODSTOW ROAD R S O U T H M E R E L D R O A 140 100 Crossway R Gallions Reach Health Centre 1 25 48 Emmanuel Baptist Manordene Road 79 STANBROOK ROAD 111 Abbey Wood A D Surgery 33 Church Bentham Road THAMESMEAD H Lakeside Crossway 165 1 Health Centre Footbridge Hawksmoor School 180 20 Lister Walk Abbey Y GODSTOW ROAD Footbridge N1 Belvedere BUR AY Central Way Wood Park OVE GROVEBURY ROAD Footbridge Y A R N T O N W Y GR ROAD A Industrial Area 242 Footbridge R Grasshaven Way Y A R N T O N W AY N 149 8 T Bentham Road Thamesmead 38 O EYNSHAM DRIVE Games N Southwood Road Bentham Road Crossway Crossway Court 109 W Poplar Place Curlew Close PANFIELD ROAD Limestone A Carlyle Road 73 Pet Aid Centre W O LV E R C O T E R O A D Y 78 7 21 Community 36 Bentham Road -

South East London Green Chain Plus Area Framework in 2007, Substantial Progress Has Been Made in the Development of the Open Space Network in the Area

All South East London Green London Chain Plus Green Area Framework Grid 6 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 56 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA06 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA06 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www. london.gov.uk/publication/all-london-green-grid-spg . -

Charlton Riverside SPD

Charlton Riverside SPD Draft February 2017 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Vision and Objectives 2 3 Context 13 4 Development Concept 29 5 Theme 1 – A Residentially Diverse Charlton Riverside 41 6 Theme 2 – An Economically Active Charlton Riverside 49 7 Theme 3 – A Connected and Accessible Charlton Riverside 61 8 Theme 4 – An Integrated and Lifetime Ready Charlton Riverside 73 Draft9 Theme 5 – A Well-designed Charlton Riverside 87 10 Theme 6 – A Sustainable and Resilient Charlton Riverside 113 11 Theme 7 – A Viable and Deliverable Charlton Riverside 121 12 Illustrative Masterplan 135 Appendices Charlton Riverside SPD | February 2017 iii List of Figures Figure Page Figure Page Figure Page 1.1 SPD Area 3 5.4 Development densities 47 8.7 Green Bridge Option 1 83 1.2 Basis of this SPD and how it should be used 5 6.1 Existing land use (at ground floor) 50 8.8 Green Bridge Option 2 84 3.1 The City in the East 14 6.2 Economic activity at Charlton Riverside 52 8.9 Green Crossing 85 3.2 Charlton Riverside 15 6.3 Angerstein and Murphy’s Wharves 53 9.1 Character areas 88 3.3 Economic activity at Charlton Riverside 17 6.4 Riverside Wharf 54 9.2 Neighbourhood and local centres 91 3.4 Existing building heights 18 6.5 Proposed ground floor uses 55 9.3 Neighbourhood Centre/High Street 92 3.5 Flood risk 20 6.6 Proposed upper floor uses 56 9.4 Retail and commercial uses 93 3.6 Public Transport Accessibility Level (PTAL) 21 6.7 Employment locations 57 9.5 Historic assets map 95 3.7 Existing open space 22 7.1 Proposed network of streets 62 9.6 Block structure -

DOWNLOAD London.PDF • 5 MB

GORDON HILL HIGHLANDS 3.61 BRIMSDOWN ELSTREE & BOREHAMWOOD ENFIELD CHASE ENFIELD TOWN HIGH BARNET COCKFOSTERS NEW BARNET OAKWOOD SOUTHBURY SOUTHBURY DEBDEN 9.38 GRANGE PARK PONDERS END LOUGHTON GRANGE BUSH HILL PARK COCKFOSTERS PONDERS END 6.83 4.96 3.41 OAKLEIGH PARK EAST BARNET SOUTHGATE 4.03 4.01 JUBILEE CHINGFORD WINCHMORE HILL BUSH HILL PARK 6.06 SOUTHGATE 4.24 CHINGFORD GREEN TOTTERIDGE & WHETSTONE WINCHMORE HILL BRUNSWICK 2.84 6.03 4.21 ENDLEBURY 2.89 TOTTERIDGE OAKLEIGH EDMONTON GREEN LOWER EDMONTON 3.10 4.11 3.57 STANMORE PALMERS GREEN HASELBURY SOUTHGATE GREEN 5.94 CHIGWELL WOODSIDE PARK PALMERS GREEN 5.23 EDMONTON GREEN 3.77 ARNOS GROVE 10.64 LARKSWOOD RODING VALLEY EDGWARE SILVER STREET MILL HILL BROADWAY 4.76 MONKHAMS GRANGE HILL NEW SOUTHGATE VALLEY HATCH LANE UPPER EDMONTON ANGEL ROAD 8.04 4.16 4.41 MILL WOODHOUSE COPPETTS BOWES HATCH END 5.68 9.50 HILL MILL HILL EAST WEST FINCHLEY 5.12 4.41 HIGHAMS PARK CANONS PARK 6.07 WEST WOODFORD BRIDGE FINCHLEY BOUNOS BOWES PARK 3.69 5.14 GREENBOUNDS GREEN WHITE HART LANE NORTHUMBERLAND PARK HEADSTONE LANE BURNT OAK WOODSIDE WHITE HART LANE HAINAULT 8.01 9.77 HALE END FAIRLOP 4.59 7.72 7.74 NORTHUMBERLAND PARK AND BURNT OAK FINCHLEY CENTRAL HIGHAMS PARK 5.93 ALEXANDRA WOOD GREEN CHURCH END RODING HIGHAM HILL 4.58 FINCHLEY 4.75 ALEXANDRA PALACE CHAPEL END 3.13 4.40 COLINDALE EAST 5.38 FULLWELL CHURCH 5.25 FAIRLOP FINCHLEY BRUCE 5.11 4.01 NOEL PARK BRUCE GROVE HARROW & WEALDSTONE FORTIS GREEN GROVE TOTTENHAM HALE QUEENSBURY COLINDALE 4.48 19.66 PINNER 3.61 SOUTH WOODFORD HENDON WEST -

Greenwich - Discover London's Secret Gardens

Greenwich - Discover London's Secret Gardens October 2015 1. Seasonal Specials JANUARY-FEBRUARY Crocuses in Eaglesfield Park Situated on top of Shooters Hill, Eaglesfield Park is the second highest point in Greater London and has excellent views across Kent to the South East and across London and the city to the North and East. It forms part of the Green Chain Walk and links Oxleas Wood with Woodlands Farm and Bostall Wood and Lesnes Abbey beyond and is permanently accessible with picnic tables, a children’s play area and a wonderfully restored wildlife pond with a surrounding meadow. http://eaglesfieldpark.org/ Snowdrops at Eltham Palace Early bulbs are clearly visable at Eltham with cyclamen, snowdrops, yellow aconites, primroses, sky-blue wood anemones and wine-coloured hellebores- http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/eltham-palace-and-gardens/things-to- see-and-do/seasonal-garden-highlights/ APRIL-MAY Explore the bluebell wood at Severndroog Castle (further Castle details below in no.3) www.severndroogcastle.org JUNE Roses can be found in bloom at Eltham Palace during summer in both the Rose Garden and the Rose Quadrant. Historic rose varieties include Rosa'Gruss an Aachen' bred in Germany in 1909. Also excellent are the indispensable hybrid musk roses such as R. 'Felicia.' Along the top of the sunken wall of the Rose Garden is a lavender hedge which, with the roses, scents the garden throughout the summer. The Rose Garden at Greenwich Park is located on the eastern side of the park and forms the backdrop to the Ranger's House, an elegant Georgian villa which was originally the residence of the Park Ranger. -

1C Herbert Road, Plumstead SE18 3TB Retail Shop to Rent London SE18 - 1C Herbert Road, Plumstead SE18 3TB Retail Shop to Rent

London SE18 - 1c Herbert Road, Plumstead SE18 3TB Retail Shop to Rent London SE18 - 1c Herbert Road, Plumstead SE18 3TB Retail Shop to Rent Property Features: ▪ Comprises ground floor shop with ancillary space on the first floor, convenient for local leisure facilities. ▪ VAT is NOT applicable to this property ▪ Total area size 55 sq m (592 sq ft) ▪ Available immediately on a new lease with terms to be agreed by negotiation. ▪ Forms part of a retail parade that serves the local area. ▪ Occupiers close by include Post Office, Co-Op Supermarket, amongst a number of restaurants/ takeaway, barber and beauty salon. Property Description: Comprises end of terrace building arranged as a ground floor shop with ancillary space on the first floor, convenient for local leisure facilities. Total area size 55 sq m (592 sq ft) London SE18 - 1c Herbert Road, Plumstead SE18 3TB Retail Shop to Rent Terms: Available on a new lease with terms to be agreed by negotiation Rent: £230.77 per week (PCM: £1,000) Deposit: 3 Months (£3,000) The incoming tenant will be responsible for the legal costs and admin fees. Rateable Value: Rateable Value – £4,000 Rates Payable – £1,964* *Note – Small business rates relief available (subject to terms) EPC: The property benefits from a C Rating. Certificate and further details available on request. Location: Plumstead is a hilly suburb known for its sprawling green spaces, notably Plumstead Common, with walking paths, tennis courts, and the wooded Slade Ravine. Herbert Road runs between Nightingale Place and Woolwich Common. The property forms part of a retail parade that serves the local area. -

Royal Artillery Barracks and Royal Military Repository Areas

CHAPTER 7 Royal Artillery Barracks and Royal Military Repository Areas Lands above Woolwich and the Thames valley were taken artillery companies (each of 100 men), headquartered with JOHN WILSON ST for military use from 1773, initially for barracks facing their guns in Woolwich Warren. There they assisted with Woolwich Common that permitted the Royal Regiment of Ordnance work, from fusefilling to proof supervising, and Artillery to move out of the Warren. These were among also provided a guard. What became the Royal Regiment Britain’s largest barracks and unprecedented in an urban of Artillery in 1722 grew, prospered and spread. By 1748 ARTILLERY PLACE Greenhill GRAND DEPOT ROAD context. The Board of Ordnance soon added a hospi there were thirteen companies, and further wartime aug Courts tal (now Connaught Mews), built in 1778–80 and twice mentations more than doubled this number by the end CH REA ILL H enlarged during the French Wars. Wartime exigencies also of the 1750s. There were substantial postwar reductions saw the Royal Artillery Barracks extended to their present in the 1760s, and in 1771 the Regiment, now 2,464 men, Connaught astonishing length of more than a fifth of a mile 0( .4km) was reorganized into four battalions each of eight com Mews in 1801–7, in front of a great grid of stables and more panies, twelve of which, around 900 men, were stationed barracks, for more than 3,000 soldiers altogether. At the in Woolwich. Unlike the army, the Board of Ordnance D St George’s A same time more land westwards to the parish boundary required its officers (Artillery and Engineers) to obtain Royal Artillery Barracks Garrison Church GRAND DEPOT RD O R was acquired, permitting the Royal Military Repository to a formal military education.