Salicylate Toxicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table S1: Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, NPV, and F1 Score of NLP Vs. ICD for Identification of Symptoms for (A) Biome Developm

Table S1: Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and F1 score of NLP vs. ICD for identification of symptoms for (A) BioMe development cohort; (B) BioMe validation cohort; (C) MIMIC-III; (D) 1 year of notes from patients in BioMe calculated using manual chart review. A) Fatigue Nausea and/or vomiting Anxiety Depression NLP (95% ICD (95% CI) P NLP (95% CI) ICD (95% CI) P NLP (95% CI) ICD (95% CI) P NLP (95% CI) ICD (95% CI) P CI) 0.99 (0.93- 0.59 (0.43- <0.00 0.25 (0.12- <0.00 <0.00 0.54 (0.33- Sensitivity 0.99 (0.9 – 1) 0.98 (0.88 -1) 0.3 (0.15-0.5) 0.85 (0.65-96) 0.02 1) 0.73) 1 0.42) 1 1 0.73) 0.57 (0.29- 0.9 (0.68- Specificity 0.89 (0.4-1) 0.75 (0.19-1) 0.68 0.97 (0.77-1) 0.03 0.98 (0.83-1) 0.22 0.81 (0.53-0.9) 0.96 (0.79-1) 0.06 0.82) 0.99) 0.99 (0.92- 0.86 (0.71- 0.94 (0.79- 0.79 (0.59- PPV 0.96 (0.82-1) 0.3 0.95 (0.66-1) 0.02 0.95 (0.66-1) 0.16 0.93 (0.68-1) 0.12 1) 0.95) 0.99) 0.92) 0.13 (0.03- <0.00 0.49 (0.33- <0.00 0.66 (0.48- NPV 0.89 (0.4-1) 0.007 0.94 (0.63-1) 0.34 (0.2-0.51) 0.97 (0.81-1) 0.86 (0.6-0.95) 0.04 0.35) 1 0.65) 1 0.81) <0.00 <0.00 <0.00 F1 Score 0.99 0.83 0.88 0.57 0.95 0.63 0.82 0.79 0.002 1 1 1 Itching Cramp Pain NLP (95% ICD (95% CI) P NLP (95% CI) ICD (95% CI) P NLP (95% CI) ICD (95% CI) P CI) 0.98 (0.86- 0.24 (0.09- <0.00 0.09 (0.01- <0.00 0.52 (0.37- <0.00 Sensitivity 0.98 (0.85-1) 0.99 (0.93-1) 1) 0.45) 1 0.29) 1 0.66) 1 0.89 (0.72- 0.5 (0.37- Specificity 0.96 (0.8-1) 0.98 (0.86-1) 0.68 0.98 (0.88-1) 0.18 0.5 (0-1) 1 0.98) 0.66) 0.88 (0.69- PPV 0.96 (0.8-1) 0.8 (0.54-1) 0.32 0.8 (0.16-1) 0.22 0.99 (0.93-1) 0.98 (0.87-1) NA* 0.97) 0.98 (0.85- 0.57 (0.41- <0.00 0.58 (0.43- <0.00 NPV 0.98 (0.86-1) 0.5 (0-1) 0.02 (0-0.08) NA* 1) 0.72) 1 0.72) 1 <0.00 <0.00 <0.00 F1 Score 0.97 0.56 0.91 0.28 0.99 0.68 1 1 1 *Denotes 95% confidence intervals and P values that could not be calculated due to insufficient cells in 2x2 tables. -

Management of Poisoning

MOH CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES December/2011 Management of Poisoning Health Ministry of Sciences Chapter of Emergency College of College of Family Manpower Authority Physicians Physicians, Physicians Academy of Medicine, Singapore Singapore Singapore Singapore Medical Pharmaceutical Society Society for Emergency Toxicology Singapore Paediatric Association of Singapore Medicine in Singapore Society (Singapore) Society Executive summary of recommendations Details of recommendations can be found in the main text at the pages indicated. Principles of management of acute poisoning – resuscitating the poisoned patient GPP In a critically poisoned patient, measures beyond standard resuscitative protocol like those listed above need to be implemented and a specialist experienced in poisoning management should be consulted (pg 55). GPP D Prolonged resuscitation should be attempted in drug-induced cardiac arrest (pg 55). Grade D, Level 3 1 C Titrated doses of naloxone, together with bag-valve-mask ventilation, should be administered for suspected opioid-induced coma, prior to intubation for respiratory insuffi ciency (pg 56). Grade C, Level 2+ D In bradycardia due to calcium channel or beta-blocker toxicity that is refractory to conventional vasopressor therapy, intravenous calcium, glucagon or insulin should be used (pg 57). Grade D, Level 3 B Patients with actual or potential life threatening cardiac arrhythmia, hyperkalaemia or rapidly progressive toxicity from digoxin poisoning should be treated with digoxin-specifi c antibodies (pg 57). Grade B, Level 2++ B Titrated doses of benzodiazepine should be given in hyperadrenergic- induced tachycardia states resulting from poisoning (pg 57). Grade B, Level 1+ D Non-selective beta-blockers, like propranolol, should be avoided in stimulant toxicity as unopposed alpha agonism may worsen accompanying hypertension (pg 57). -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

Salsalate Tablets, USP 500 Mg and 750 Mg Rx Only

SALSALATE RX- salsalate tablet, film coated ANDAPharm LLC Disclaimer: This drug has not been found by FDA to be safe and effective, and this labeling has not been approved by FDA. For further information about unapproved drugs, click here. ---------- Salsalate Tablets, USP 500 mg and 750 mg Rx Only Cardiovascular Risk NSAIDs may cause an increase risk of serious cardiovascular thrombotic events, myocardial infarction, and stroke, which can be fatal. This risk may increase with duration of use. Patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease may be at greater risk. (See WARNINGS and CLINICAL TRIALS). Salsalate tablets, USP is contraindicated for the treatment of perioperative pain in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (See WARNINGS). Gastrointestinal Risk NSAIDs cause an increased risk of serious gastrointestinal adverse events including bleeding, ulceration, and perforation of the stomach or intestines, which can be fatal. These events can occur at any time during use and without warning symptoms. Elderly patients are at greater risk for serious gastrointestinal events. (See WARNINGS). DESCRIPTION Salsalate, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent for oral administration. Chemically, salsalate (salicylsalicylic acid or 2-hydroxybenzoic acid, 2-carboxyphenyl ester) is a dimer of salicylic acid; its structural formula is shown below. Chemical Structure: Inactive Ingredients: Colloidal Silicon Dioxide, D&C Yellow #10 Aluminum Lake, Hypromellose, Microcrystalline Cellulose, Sodium Starch Glycolate, Stearic Acid, Talc, Titanium Dioxide, Triacetin. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Salsalate is insoluble in acid gastric fluids (<0.1 mg/mL at pH 1.0), but readily soluble in the small intestine where it is partially hydrolyzed to two molecules of salicylic acid. -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

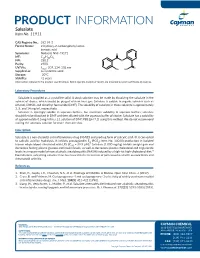

PRODUCT INFORMATION Salsalate Item No. 11911 CAS Registry No.: 552-94-3 Formal Name: 2-hydroxy-2-carboxyphenyl ester- benzoic acid Synonyms: Nobacid, NSC 49171 O MF: C14H10O5 FW: 258.2 O Purity: ≥98% UV/Vis.: λ: 207, 234, 308 nm O max OH HO Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Salsalate is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the salsalate in the solvent of choice, which should be purged with an inert gas. Salsalate is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide (DMF). The solubility of salsalate in these solvents is approximately 3, 5, and 14 mg/ml, respectively. Salsalate is sparingly soluble in aqueous buffers. For maximum solubility in aqueous buffers, salsalate should first be dissolved in DMF and then diluted with the aqueous buffer of choice. Salsalate has a solubility of approximately 0.5 mg/ml in a 1:1 solution of DMF:PBS (pH 7.2) using this method. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. Description Salsalate is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and prodrug form of salicylic acid.1 It is converted to salicylic acid by hydrolysis. It inhibits prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Item No. 14010) production in isolated 2 human whole blood stimulated with LPS (IC50 = 39.9 µM). Salsalate (1,000 mg/kg) inhibits weight gain and decreases fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels, as well as decreases plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) induced by a high-fat high-cholesterol diet.3 Formulations containing salsalate have been used in the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Acute Poisoning: Understanding 90% of Cases in a Nutshell S L Greene, P I Dargan, a L Jones

204 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.2004.027813 on 5 April 2005. Downloaded from Acute poisoning: understanding 90% of cases in a nutshell S L Greene, P I Dargan, A L Jones ............................................................................................................................... Postgrad Med J 2005;81:204–216. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024794 The acutely poisoned patient remains a common problem Paracetamol remains the most common drug taken in overdose in the UK (50% of intentional facing doctors working in acute medicine in the United self poisoning presentations).19 Non-steroidal Kingdom and worldwide. This review examines the initial anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), benzodiaze- management of the acutely poisoned patient. Aspects of pines/zopiclone, aspirin, compound analgesics, drugs of misuse including opioids, tricyclic general management are reviewed including immediate antidepressants (TCAs), and selective serotonin interventions, investigations, gastrointestinal reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) comprise most of the decontamination techniques, use of antidotes, methods to remaining 50% (box 1). Reductions in the price of drugs of misuse have led to increased cocaine, increase poison elimination, and psychological MDMA (ecstasy), and c-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) assessment. More common and serious poisonings caused toxicity related ED attendances.10 Clinicians by paracetamol, salicylates, opioids, tricyclic should also be aware that severe toxicity can result from exposure to non-licensed pharmaco- -

NON-HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS May Be Disposed of Via Sanitary Sewer Or Solid Waste

NON-HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS May Be Disposed Of Via Sanitary Sewer or Solid Waste (+)-A-TOCOPHEROL ACID SUCCINATE (+,-)-VERAPAMIL, HYDROCHLORIDE 1-AMINOANTHRAQUINONE 1-AMINO-1-CYCLOHEXANECARBOXYLIC ACID 1-BROMOOCTADECANE 1-CARBOXYNAPHTHALENE 1-DECENE 1-HYDROXYANTHRAQUINONE 1-METHYL-4-PHENYL-1,2,5,6-TETRAHYDROPYRIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE 1-NONENE 1-TETRADECENE 1-THIO-B-D-GLUCOSE 1-TRIDECENE 1-UNDECENE 2-ACETAMIDO-1-AZIDO-1,2-DIDEOXY-B-D-GLYCOPYRANOSE 2-ACETAMIDOACRYLIC ACID 2-AMINO-4-CHLOROBENZOTHIAZOLE 2-AMINO-2-(HYDROXY METHYL)-1,3-PROPONEDIOL 2-AMINOBENZOTHIAZOLE 2-AMINOIMIDAZOLE 2-AMINO-5-METHYLBENZENESULFONIC ACID 2-AMINOPURINE 2-ANILINOETHANOL 2-BUTENE-1,4-DIOL 2-CHLOROBENZYLALCOHOL 2-DEOXYCYTIDINE 5-MONOPHOSPHATE 2-DEOXY-D-GLUCOSE 2-DEOXY-D-RIBOSE 2'-DEOXYURIDINE 2'-DEOXYURIDINE 5'-MONOPHOSPHATE 2-HYDROETHYL ACETATE 2-HYDROXY-4-(METHYLTHIO)BUTYRIC ACID 2-METHYLFLUORENE 2-METHYL-2-THIOPSEUDOUREA SULFATE 2-MORPHOLINOETHANESULFONIC ACID 2-NAPHTHOIC ACID 2-OXYGLUTARIC ACID 2-PHENYLPROPIONIC ACID 2-PYRIDINEALDOXIME METHIODIDE 2-STEP CHEMISTRY STEP 1 PART D 2-STEP CHEMISTRY STEP 2 PART A 2-THIOLHISTIDINE 2-THIOPHENECARBOXYLIC ACID 2-THIOPHENECARBOXYLIC HYDRAZIDE 3-ACETYLINDOLE 3-AMINO-1,2,4-TRIAZINE 3-AMINO-L-TYROSINE DIHYDROCHLORIDE MONOHYDRATE 3-CARBETHOXY-2-PIPERIDONE 3-CHLOROCYCLOBUTANONE SOLUTION 3-CHLORO-2-NITROBENZOIC ACID 3-(DIETHYLAMINO)-7-[[P-(DIMETHYLAMINO)PHENYL]AZO]-5-PHENAZINIUM CHLORIDE 3-HYDROXYTROSINE 1 9/26/2005 NON-HAZARDOUS CHEMICALS May Be Disposed Of Via Sanitary Sewer or Solid Waste 3-HYDROXYTYRAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE 3-METHYL-1-PHENYL-2-PYRAZOLIN-5-ONE -

Salicylate, Diflunisal and Their Metabolites Inhibit CBP/P300 and Exhibit Anticancer Activity

RESEARCH ARTICLE Salicylate, diflunisal and their metabolites inhibit CBP/p300 and exhibit anticancer activity Kotaro Shirakawa1,2,3,4, Lan Wang5,6, Na Man5,6, Jasna Maksimoska7,8, Alexander W Sorum9, Hyung W Lim1,2, Intelly S Lee1,2, Tadahiro Shimazu1,2, John C Newman1,2, Sebastian Schro¨ der1,2, Melanie Ott1,2, Ronen Marmorstein7,8, Jordan Meier9, Stephen Nimer5,6, Eric Verdin1,2* 1Gladstone Institutes, University of California, San Francisco, United States; 2Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, United States; 3Department of Hematology and Oncology, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 4Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 5University of Miami, Gables, United States; 6Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Miami, United States; 7Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States; 8Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute, Philadelphia, United States; 9Chemical Biology Laboratory, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, United States Abstract Salicylate and acetylsalicylic acid are potent and widely used anti-inflammatory drugs. They are thought to exert their therapeutic effects through multiple mechanisms, including the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenases, modulation of NF-kB activity, and direct activation of AMPK. However, the full spectrum of their activities is incompletely understood. Here we show that salicylate specifically inhibits CBP and p300 lysine acetyltransferase activity in vitro by direct *For correspondence: everdin@ competition with acetyl-Coenzyme A at the catalytic site. We used a chemical structure-similarity gladstone.ucsf.edu search to identify another anti-inflammatory drug, diflunisal, that inhibits p300 more potently than salicylate. At concentrations attainable in human plasma after oral administration, both salicylate Competing interests: The and diflunisal blocked the acetylation of lysine residues on histone and non-histone proteins in cells. -

Medications & Supplements to Avoid Before Procedures

Medications & Supplements to Avoid Before Procedures Do not ingest any brand of aspirin, or any aspirin-containing medication, any MAO inhibiting, or any serotonin medications, for 14 prior to and 14 days after surgery. Disclose every medication, supplement, etc. With Dr. Rau and your anesthesiologist. Aspirin and aspirin-containing products, as well as some supplements and herbals, may inhibit blood clotting and cause difficulties during and after surgery. If you need an aspirin-free fever reducer and pain reliever, take Tylenol. Also, if you smoke, you must refrain for at least a month prior to a month after your surgery date. Smoking significantly reduces your body’s circulation and vascularity, meaning that your tissues won’t receive all the oxygen needed for proper healing. DIET PILLS, FAT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS AND STACKERS: Please stop taking these pills at least 2 weeks before surgery. Many of these pills contain anticoagulants and can seriously impede your body's ability to clot sufficiently, resulting in hemorrhaging. Many of them also contain ephedra and caffeine, which can affect your anesthetic medications. Remember: if you take antibiotics or if you stop oral contraceptive pills for surgery, use an alternative method of birth control. A Aspirin, Advil, Actifed, Acuprin, Addaprin, Alka Seltzer, Alpha Omega (fish oil), Aluprin, Amitriptyline, Anacin, Ansaid, Anodynos, Analval, Anodynos, Ansaid, Argesic, Arthra-G, Arthralgen, Arthropan, Ascodeen, Ascriptin, Aspir-lox, Asperi-mox, Aspirbuf, Aspercin, Aspergum, Axotal, Azdone, -

Be Aware of Some Medications

Aspirin, Pain Relievers, Cold and Fever Remedies and Arthritis Medications when you have asthma, rhinitis or nasal polyps For some people with asthma, rhinitis and nasal polyps, medications such as acetylsalicylic acid or ASA and some arthritis medications can trigger very severe asthma, rhinitis, hives, swelling and shock. If you react to one of these medications, you will probably react to all of the others as well. There are many medications and products that contain ASA. This handout names some. Since new products are coming out all of the time, it is best to check with the pharmacist before using. Check the label yourself as well. If you react to these medications you must: Avoid these medications and products at all times. Let your doctor know right away if you have taken one of the medications and develop symptoms. Check the ingredients on the label yourself. Ask your pharmacist, doctor or other health care provider if you have questions. Get a medical alert bracelet or card that says you are allergic to ASA. Tell all of your health care providers that you are allergic to ASA. For pain control, use acetaminophen. Some products with acetaminophen are Atasol, Tempra, Tylenol and Novo-Gesic. Most people allergic to ASA can use acetaminophen. Firestone Institute for Respiratory Health St. Joseph’s Hospital McMaster University Health Sciences Some Products that Contain ASA 217s, 217s Strong D P 222s Doan’s Backache Pills Pepto-Bismol 282s, 282s Meps Dodd’s Tablets – All Percodan 292s Dolomine 37 Phenaphen with Codeine 692s Dristan Extra Strength PMS-Sulfasalazine A Dristan – All kinds AC&C R AC&C Extra Strength E Ratio-Oxycodan Acetylsalicylic Acid EC ASA Relief ASA Achrocidin Ecotrin – All kinds Robaxisal – All kinds Aggrenox Endodan Alka Seltzer – All kinds Enteric coated ASA S Anacin – All kinds Enteric coated aspirin Salazopyrin Antidol Entrophen – All kinds Salazopyrin Enema Apo-ASA Excedrin Salofalk Enema Apo-Asen Sulfasalazine Arco Pain Tablet F Arthrisin Fiorinal T Artria SR Fiorinal with Codeine Tri-Buffered ASA ASA, A.S.A. -

WO 2010/099522 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 2 September 2010 (02.09.2010) WO 2010/099522 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 45/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/4164 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/4045 (2006.01) A61K 31/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2010/025725 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 1 March 2010 (01 .03.2010) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (26) Publication Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/156,129 27 February 2009 (27.02.2009) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, HELSINN THERAPEUTICS (U.S.), INC.