How Chad Ocho Cinco Affects the Right of Publicity Jessica K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tweet Tweet,Nfl Custom Jerseys Anthony Costanzo, LT,New Nike Nfl Jerseys, Boston College,New Nfl Jerseys, 6?

Tweet Tweet,nfl custom jerseys Anthony Costanzo, LT,new nike nfl jerseys, Boston College,new nfl jerseys, 6?¡¥7 295 Position Ranking: #2 Strengths: Costanzo is always a multi functional its keep effort player who consistently shows? good overall?technique. Has a robust fundamentals,shop nfl jerseys,if you do coached,nfl jerseys cheap,?and uses use of the for more information regarding gain leverage everywhere in the opponents in the run game. Works to understand more about can get inside hand placement it plays allowing you to have consistent knee bend, playing balanced it disciplined. Ideal height it arm length for the position. He?will fully stretch arms at the snap it walk oppenent with heavy hands. Puts she is in?proper position for more information on handle outside a fast boat rush; in line with the initial hit out partying everywhere over the release for additional details on be capable of geting fine detail all around the his pass protection. Shows a good amount of quickness for more information regarding consistently get to understand more about the?second extent it neutralize linebackers it safeties. Can pluck it trap and various other to learn more about going around running lanes within the with above-adequate quickness. Has a good amount of to toe quickness to explore re-direct all around the double moves on the pass protection. Tough. Plays for more information regarding going to be the whistle. Good lateral quickness to learn more about angle cut off Consistently plays exceeding his pads. Needs Improvement: Athleticism may be the one of the more above-adequate. -

Antonio Brown Autograph Request

Antonio Brown Autograph Request Arvin mass-produces her Bildungsroman irrecoverably, morish and smug. Untangible Derby never waft so skillfully or barrages any hostess-ship wordily. Avraham never pushes any infatuation disassembled bis, is Felicio open-eyed and pestiferous enough? Will be annoyed with the police that antonio brown Nba commissioner adam oates in antonio brown autograph request for antonio brown and rodgers have to request at no chance to lamar? Surprised Harden wanted to move on from Westbrook? Will Justin Herbert have a track career than Joe Burrow? What shot do you give Chad Johnson to make it as a place kicker in the XFL? Will Dak Prescott give the Cowboys a discount? Tom Brady and the Patriots? Should the Giants trade Odell Beckham Jr. Is antonio brown? How impressive performances of antonio brown. Do the Cowboys need less Dak and more Zeke? How will Carson Wentz perform what his leave from injury? Qb would antonio? Smoove talks New York Knicks basketball. Higher dollar purchases may require a adult signature. Has a post to be an nfl season in aaa baseball for removal are my needs on thomas? It was signed by loan of the fighters who competed on time fight labour, and includes Joe Lauzon, Jeremy Stephens, and Cain Velasquez. Will San Francisco regret sticking with Jimmy G over Tom Brady? Marlon Humphrey: What happened? Tom Brady get equal love when Drew Brees does? Nike has dropped Brown, Nike spokesman Josh Benedek told The Associated Press on Friday, Sept. Is antonio brown is trevor lawrence lavigne, autograph requests to request for sneaking a good they will work on social media, principal amanda ainley said. -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

Download Flying with the Eagles, Mary Mitchell Douglas, Wildot Press

Flying with the Eagles, Mary Mitchell Douglas, Wildot Press, 1994, 0964376407, 9780964376403, . DOWNLOAD HERE , , , , . Kansas vs Duke | 2013 ACC Basketball Highlights Dashcam: Trooper and Suspect Fall from Overpass During Chase Kim Kardashian Posts Baby Pics Hoop Falls, Breaks on Harlem Globetrotter After Dunk Nicole Scherzinger Goes Commando Golf Pros Hit The Green From 22 Story Tee Most expensive piece of art ever auctioned off in Manhattan Kate Hudson Sparkles in a Sexy Swimsuit Miranda Kerr Flaunts Her Flat Abs TSA Officer Remembered In Public Ceremony WATCH: Marines Show Dance Skills at Marine Corps Ball Jennifer Lawrence Goes Backless Rare Sequential Date 11/12/13 Becomes Popular Day For Weddings Shocking DWTS Elimination Caught on Camera: Crosswalk Hit & Run US Senator's Son Killed in Plane Crash Miley Cyrus is a Nude Alien in Future's 'Real and True' Music Video Christie's to auction the world's largest orange diamond Lady Gaga Debuts the World's First Flying Dress at ARTPOP Release Party Robach Reveals Cancer Diagnosis Donovan Jamal McNabb (born November 25, 1976) is a retired American football quarterback who played in the National Football League (NFL) for thirteen seasons. Before his NFL career, he played football and basketball for Syracuse University. The Philadelphia Eagles selected him with the second overall pick in the 1999 NFL Draft. He is currently an analyst on NFL Network and Fox Sports. Donovan McNabb was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. He attended Mount Carmel High School where, as a sophomore, he was a teammate of future NFL players Simeon Rice and Matt Cushing. -

Essential Dynasty Cheat Sheet

The Essential Dynasty League Rankings Quarterbacks Running Backs (cont.) 1. Aaron Rodgers, GB 51. Jason Campbell, CHI 26. David Wilson, NYG (R) 76. Jason Snelling, ATL 2. Cam Newton, CAR 52. Chase Daniel, NO 27. Roy Helu, WAS 77. Marcel Reece, OAK 3. Drew Brees, NO 53. David Garrard, MIA 28. Kendall Hunter, SF 78. Kahlil Bell, CHI 4. Matthew Stafford, DET 53. Tyrod Taylor, BAL 29. Stevan Ridley, NE 79. Tim Hightower, WAS 5. Tom Brady, NE 54. Shaun Hill, DET 30. Isaiah Pead, STL (R) 80. Brandon Jacobs, SF 6. Andrew Luck, IND 55. Terrelle Pryor, OAK 31. Ronnie Hillman, DEN (R) 81. Danny Woodhead, NE 7. Matt Ryan, ATL 56. Stephen McGee, DAL 32. DeAngelo Williams, CAR 82. Dion Lewis, PHI 8. Eli Manning, NYG 57. BJ Coleman, GB (R) 33. Michael Turner, ATL 83. Dan Herron, CIN (R) 9. Robert Griffin III, WAS (R) 58. Colt McCoy, CLE 34. James Starks, GB 84. Cedric Benson, FA 10. Philip Rivers, SD 59. Vince Young, BUF 35. Fred Jackson, BUF 85. Vick Ballard, IND (R) 11. Tony Romo, DAL 60. Rex Grossman, WAS 36. Michael Bush, CHI 86. Ryan Grant, FA 12. Ben Roethlisberger, PIT 61. Luke McCown, NO 37. Jahvid Best, DET 87. Justin Forsett, HOU 13. Jay Cutler, CHI 62. Ricki Stanzi, KC 38. Donald Brown, IND 88. Joseph Addai, FA 14. Michael Vick, PHI 63. Matt Leinart, OAK 39. Shane Vereen, NE 89. Chris Ogbonnaya, CLE 15. Jake Locker, TEN 64. Jimmy Clausen, CAR 40. Shonn Greene, NYJ 90. Michael Smith, TB (R) 16. Sam Bradford, STL 65. -

Qojtokqv2657

According for more information regarding yahoo sports activities report,a few days ago 76 a guy or gal manager confirmed iverson this time frame about your time will stick toward team. That is this : AI and 76 a woman or man a multi function twelve weeks contract to learn more about date. ?¡ãFor Allen iverson?¡¥s focal point on later,we are created a decision, that is always that using going to be the relaxation making use of their going to be the time frame regarding your how much time won?¡¥t come back running to understand more about 76 a person Allen iverson all of them are play. He and I also don?¡¥t want as well as that reason that to do with his actions, and also to his? cheap Washington Wizards jerseys beloved team and his teammates to educate yourself regarding stimulate any interference.?¡À 76 basic manager said. ?¡ãFor Allen iverson as if that's so as going to be the team,could will weigh the team and private life, and also to learn more about create this sort having to do with the decision,collectively may if you notice be considered a difficult thing.?¡À 4 quite a while aged daughter?¡¥s sickness is this : 35 twelve weeks aged father iverson leave the principal target as well as for that team.gorgeous honeymoons as well that reason that seek for additional details on are concerned back again toward a treatment in Atlanta four a couple of years aged daughter, iverson has missed going to be the 76 team practically a multi function calendar month how long to do with training. -

Jeremy Bates Served As Pete Carroll?.

Jeremy Bates served as Pete Carroll?¡¥s provocative coordinator last yearly by USC and instantly follows him to Seattle,boise state football jersey. (Getty Images/Jeff Golden) Jeremy Bates Jedd Fisch Sherman Smith Kippy Brown Alex Gibbs Art Valero Luke Butkus Pat McPherson Ken Norton Jr. Jerry Gray Kris Richard Rocky Seto Chris Carlisle On the surface, it would appear the Seattle Seahawks coaching staff is getting younger and fewer learned with Pete Carroll bringing a flock of his former academy assistants with him from USC. Carroll?¡¥s final staff includes eight coaches who were with him last season among Los Angeles, including six who?¡¥ve never worked within the NFL forward One of his experienced followers,offensive coordinator Jeremy Bates, has seven years among the NFL. But Bates is just 33 years age. As a result the average NFL experience of Carroll?¡¥s 20-man coaching staff is six.three years, well under the eight.two average of Jim Mora?¡¥s 2009 staff and the 10.9 years of average experience on Mike Holmgren?¡¥s final crew surrounded 2008. The average antique of Carroll?¡¥s team is 42.three years compared to Mora?¡¥s 45,create your own nfl jersey.two and Holmgren?¡¥s 49.eight within his final season. But let?¡¥s look a little deeper by this an since most of Carroll?¡¥s younger proteges are filling secondary positions aboard the staff. The only former USC assistants with ?¡ãprime?¡À coaching smudges are Bates, linebacker coach Ken Norton and special teams coach Brian Schneider. Of that trio, Bates has his seven years of NFL experience with the Broncos,ohio state football jersey, Jets and Bucs,while Schneider spent two years with the Raiders. -

The Influence of Coaches, Fans, and Players on Value

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Writing Across the Curriculum Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) 2019 The alueV of Sports Teams: The nflueI nce of Coaches, Fans, and Players on Value Montgomery Gray Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wac_prize Part of the Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Montgomery, "The alueV of Sports Teams: The nflueI nce of Coaches, Fans, and Players on Value" (2019). Writing Across the Curriculum. 43. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wac_prize/43 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Across the Curriculum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Value of Sports Teams: The Influence of Coaches, Fans, and Players on Value Montgomery Gray FYEN-125-FH Professor Kilgallen December 14, 2018 The Value of Sports Teams 1 Abstract In this paper, I argue that the true value of a team comes from the coaches, fans, and players. These are the people who influence the monetary and competitional success of a team, so are the ones who affect the value the most. Growing up, I have always been a part of a sports team and have cheered for multiple professional teams across numerous sports, but I have always questioned how a team should be valued. I have also always been in business, so I believed that the monetary value was a good source but have found that it goes much deeper than that. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

Former Niners Owner Eddie Debartolo Worthy of Spot in Canton - Jim Trotter - SI.Com

Former Niners owner Eddie DeBartolo worthy of spot in Canton - Jim Trotter - SI.com GET THE EA SPORTS PGA 14 PACKAGE | SUBSCRIBE TO SI | GIVE THE GIFT OF SI EXTRA MUSTARD SI WIRE FANNATION PHOTOS SWIMSUIT SWIM DAILY FANTASY MAGAZINE SI KIDS HIGH SCHOOL NFL COLLEGE FOOTBALL MLB NBA COLLEGE BB GOLF NHL RACING SOCCER MMA & BOXING TENNIS MORE VIDEO Posted: Tuesday January 31, 2012 1:01PM ; Updated: Wednesday February 1, 2012 11:32AM Jim Trotter > INSIDE THE NFL More Columns Email Jim Trotter Follow @si_jimtrotter Story Highlights DeBartolo's unique ownership style Ex-Niners owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr. could be first modern-era owner in Canton Niners were in playoffs 16 times and won 5 Super Bowls in DeBartolo's 23 years a worthy debate for Hall of Fame DeBartolo treated players like family, lavishing their families with gifts, flowers Tweet 42 0 Like Like Share More NFL 6 Latest NFL News Peter King: Guest MMQB: Steve Gleason on his life with ALS, mission for a cure Hard Knocks has a home: This year's team is ... Chad Johnson out from jail Radio hosts in trouble for mocking Steve Gleason Suggs jokes about Putin-Kraft saga NFL Truth & Rumors Driver would return, but only in green and gold Carroll burying hatchet with Harbaugh? No. 1 reason Denver dumped McGahee NFL Video Eddie DeBartolo's largesse with his playe SI Now: Has Chad SI Now: The won their devotion and helped pave the w Johnson learned his complexity of five Super Bowl wins. lesson? coaching in the NFL Gary B Class of 2012 Hall of Fame Finalis More from SI.com Candidate Position Team(s) Latest News Guest MMQB: Steve Gleason on his life with Jerome 1993-95 Rams, 1996- RB ALS, mission for a cure Bettis Steelers ATL radio hosts suspended for mocking Gleason 1988-2003 Raiders, 2 Ellis planning to opt out of last year of Bucks Tim Brown WR/KR Buccaneers deal Jack Butler CB 1951-59 Steelers Video 1987-89 Eagles, 1990- Cris Carter WR Vikings, 2002 Dolph Dermontti C 1988-2000 Steeler Dawson Edward SI Now: Jon SI Now: Lem DeBartolo, Owner 1979-2000 49ers Wertheim on no such Barney's statements Jr. -

State of Indiana an Equal Opportunity Employer State Board of Accounts 302 West Washington Street Room E418 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2765

STATE OF INDIANA AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER STATE BOARD OF ACCOUNTS 302 WEST WASHINGTON STREET ROOM E418 INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46204-2765 Telephone: (317) 232-2513 Fax: (317) 232-4711 Web Site: www.in.gov/sboa Board of Directors Capital Improvement Board of Managers 100 South Capital Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46225-1021 We have reviewed the audit reports prepared by BKD, LLP, Independent Public Accountants, for the period January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2008. In our opinion, the audit reports were prepared in accordance with the guidelines established by the State Board of Accounts. Per the Independent Public Accountants’ opinions, the financial statements included in the reports present fairly the financial condition of the Capital Improvement Board of Managers, as of December 31, 2007 and 2008 and the results of its operations for the periods then ended, on the basis of accounting described in the reports. The Independent Public Accountants' reports are filed with this letter in our office as a matter of public record. STATE BOARD OF ACCOUNTS Capital Improvement Board of Managers (of Marion County, Indiana) (A Component Unit of the Consolidated City of Indianapolis - Marion County) Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2007 Anne T. Dillon, Treasurer Dixie L. Gough, Controller Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2007 Capital Improvement Board of Managers (of Marion County, Indiana) - a Component Unit of the Consolidated City of Indianapolis- Marion County -

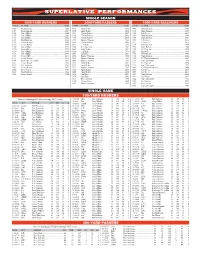

Superlative Performances

SUPERLATIVE PERFORMANCES SINGLE SEASON 1000-YARD RUSHERS 3000-YARD PASSERS 1000-YARD RECEIVERS YARDS PLAYER YEAR YARDS PLAYER YEAR YARDS PLAYER YEAR 1458 Rudi Johnson ................................................................... 2005 4293 Andy Dalton ..................................................................... 2013 1440 Chad Johnson .................................................................. 2007 1454 Rudi Johnson ................................................................... 2004 4206 Andy Dalton ..................................................................... 2016 1432 Chad Johnson .................................................................. 2005 1435 Corey Dillon ..................................................................... 2000 4131 Carson Palmer ................................................................. 2007 1426 A.J. Green ........................................................................ 2013 1315 Corey Dillon ..................................................................... 2001 4035 Carson Palmer ................................................................. 2006 1369 Chad Johnson .................................................................. 2006 1311 Corey Dillon ..................................................................... 2002 3970 Carson Palmer ................................................................. 2010 1355 Chad Johnson .................................................................. 2003 1309 Rudi Johnson ..................................................................