Learning to Pray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Teresa of Avila Speaks on Mental Prayer

The Published Articles of Ernest E. Larkin, O.Carm. St. Teresa of Avila Speaks on Mental Prayer St. Teresa of Avila Speaks on Mental Prayer “We need no wings to go in search of First, we must be searching for God. God, but have only to find a place where we If God is just a name, if His love for us is an can be alone and look upon Him present abstract truth which we believe but do not within us.” These words were written by St. realize, we will hardly search for Him. Teresa of Avila in her book The Way of Mental prayer is too difficult for that. It will Perfection. lack appeal. If, on the other hand, we are St. Teresa of Avila learned as a small convinced that God is in Teresa’s words “a child that one had to die in order to see God. better prize than any earthly love,” if we Little Teresa wanted to see God. Practical and realize that we actually have within us courageous by temperament she devised a something incomparably more precious than scheme. She and her brother, Rodrigo, would anything we see outside, then we will desire to go to the land of the Moors. There they would enter within ourselves and to seek God. When surely be martyred and Heaven would receive we are convinced that He cares for us and them. Very early one morning the two waits for us, we will have the security and the children stole away from their home and courage to love Him in return. -

Saint Francis Xavier Parish March 1, 2020

SAINT FRANCIS XAVIER PARISH MARCH 1, 2020 ‘The Lord God formed man out of the clay of the ground and blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and so man became a living being.’ ~Genesis 2:7 OUR MISSION STATEMENT ST. FRANCIS XAVIER IS A CATHOLIc- Jesuit parish Ignited by the Eucharist To PRAY, SERve, DO JUSTIce, and LoVE. "Turn away from sin and be faithful to the Gospel" On the first day of Lent we bless ashes and we wear them. We wear them as a sign of penance during this season of penance. We wear them also as a badge of who we are as Christians, followers of Christ, committed to him and to what he stands for. Everyone who sees us will witness this badge of our Christian commitment. Our public proclamation of who we are demands that we follow up with action. The Lenten readings summon us to return to a God who is slow to anger and rich in mercy, who gives back the joy of salvation and sustains a willing spirit and who knows how our hearts can turn quietly to him. Paul summons Christians to be ambassadors to reconciliation, because God made him who did not know sin to be sin, so that in him we might become the very holiness of God. Turn away from accusation turn toward embrace Turn away from judgment turn toward acceptance Turn away from exclusion turn toward belonging…. Ash Wednesday is a peculiar liturgical celebration that fascinates us. Its distinguish- ing mark is the tracing of a black cross, made out of ashes, across the forehead. -

Devotions Practiced by the Archconfraternity None of the Practices of Piety Recommended Here Oblige Under Pain of Sin, Mortal Or Venial

Devotions practiced by the Archconfraternity None of the practices of piety recommended here oblige under pain of sin, mortal or venial. To become a member of this Archconfraternity it suffices to have one’s name inscribed on the register of the members. Nevertheless, as the end of this pious association is to serve and honour the Blessed Virgin, invoked under the title of Mother of Perpetual Succour, the members should earnestly endeavour to ensure the maternal protection of Mary by having perpetual recourse to Her. What use, indeed, would it be to have the honour of being numbered with the privileged children of Mary, unless at the same time we honour Her by a more assiduous and more fervent devotion? The members are therefore strongly recommended, 1. To wear a medal of Our Mother of Perpetual Succour and St Alphonsus. 2. To place in their houses a Picture of Our Mother of Perpetual Succour. They will not fail to honour Her as the Patron and Protectress of their families, and they will say their usual prayers before this Picture or one of St Alphonsus. 3. To say every morning and evening, on their knees, three Hail Mary’s to Our Mother of Perpetual Succour, and a Gloria in honour of St Alphonsus, with the following ejaculations: “O Mary, Mother of Perpetual Succour, pray for me! My Protector Saint Alphonsus, in all my wants, make me have recourse to Mary!” 4. To choose a day every month on which to renew their consecration to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to St Alphonsus, and, if possible, to receive Holy Communion for the intentions indicated in no. -

Download Praying with Saint Francis Xavier

Praying with Saint Francis Xavier The Novena of Grace Praying with St Francis Xavier The Novena of Grace The Church has always rejoiced in the “great cloud of witnesses”1 who are the saints. These men and women, over the generations and in so many places, have shown what it is to live the Christian life, sometimes to the point of surrendering their own lives in martyrdom. Their earthly lives may have ended but their prayers continue in heaven. The Church has long believed that the saints intercede on our behalf, asking God for the graces and blessings which we forget to ask for or for which we find no time to pray: “Their intercession is their most exalted service to God’s plan. We can and should ask them to intercede for us and for the whole world.”2 Devotion to Francisco Xavier has always been immensely popular as he fires the imagination with his heroic travels to distant peoples and lands across the globe. This novena is nine days of prayer, in the company of St Francis Xavier, through the letters he wrote. As a Jesuit, Francisco underwent and then, in turn, led others through the Spiritual Exercises of his great friend St Ignatius Loyola. His writings reflect the spiritual insights and preoccupations of the Spiritual Exercises. We pray to know ourselves better, to discern the will of God for each of us in the daily unfolding of our lives, to hear and generously answer Christ’s call to follow him, whatever the cost, and to understand that everything is unmerited gift from God, poured out lavishly upon us “as rays from the sun or waters from the spring.”3 The present form of the Novena was begun in the seventeenth century by Fr Marcello Mastrilli SJ (1603-37). -

Ignatian Spirituality and Theology

IGNATIAN SPIRITUALITY AND THEOLOGY Bernard Sesboüé, SJ Professor emeritus Fundamental and dogmatic theology Centre Sèvres, Paris, France here certainly must be an “Ignatian” way of doing theology. Of course it would not be the only way and Tother spiritual families have been inspired by other “ways of proceeding.” In these pages I would like to allude to the method that seems to me to be based on the spirituality of St. Ignatius and are illustrated by several great Jesuit theologians of the 20th century. Ignatius of Loyola and theology St. Ignatius never was a theologian by trade. He only became a student himself late in life. But he took his theological formation in Paris very seriously, because he was convinced that he could not “help souls” without first doing the necessary studies. He studied during troubled times in the context of the early Reformation in Paris.1 Ignatius and his companions sided with moderates who sought to reconcile the desire for a faith that was more interior and personal with the doctrinal authority of the Church. They were open to the progress of the Renaissance; they favored the study of the “three languages,” Hebrew, Greek and Latin. But they wanted to preserve classical references to scholastic theology as found in its better representatives. Ignatius was very vigilant in what concerned orthodoxy and “feeling with the Church,” but at the same time he advised his companion Bobadilla to combine NUMBER 115 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 27 IGNATIAN SPIRITUALITY AND THEOLOGY positive theology with scholastic theology, which involved the study of languages. -

The Practice of Mental Prayer

The Practice of Mental Prayer by MATTIA DA SALÒ Translated by Br Patrick Colbourne O.F.M.Cap. There is general consensus among scholars that The Practice of Mental Prayer is Bellintani’s ascetical masterpiece. What is more, it is also one of those works similar to The Contempt of the World by Innocent III, The Dialogue of Divine Providence by Catherine of Siena, The Treatise on Purgatory by Saint Catherine of Genoa, The Spiritual Combat by Scupoli that seems to epitomise a era of spiritual writings. In fact while it is regarded as one of the most ripe fruits of the Capuchin Italian sixteenth century and, perhaps, the most mature product of a particular kind of spirituality, on a broader scale it represents the pre-eminently apostolic aspect of the new Franciscan reform which seems to capture and fully exemplify its two outstanding characteristics: contemplative solitude and preaching the Gospel. Bellintani’s work, which is presented as a method and guide for mental prayer was generally accepted by popular piety as one of the most widely read and enjoyed ascetical works by the Christian community. This is substantiated by the number of editions which continued to be published into the seventeenth century and by translations into French, Latin and Spanish which in all numbered about fifty. What is more it was recommended by Saint Charles Borromeo, prescribed for Confraternities of Penance by the Archbishop of Avignon, Francesco M. Taugi, praised by the Spirituals of the day, used by prayer groups during the Forty Hours and flicked through by everyone. -

Ignatian Spirituality and the Spiritual Exercises

Ignatian Spirituality and the Spiritual Exercises Debra Mooney, Ph.D. Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus, articulated an experience and approach to life and God, a spirituality, which continues to thrive after hundreds of years. Ignatian spirituality: • Is centered around the belief that God can be found in all things Taking time each day to reflect upon God’s moment-by-moment presence builds this amazing awareness. • Is action-oriented God invites the person to grow increasingly competent, caring, and loving, to relieve injustices and suffering in our world “for the greater glory of God.” • Engages and builds self-awareness The person enlists affect, imagination, and intellect to know how greatly God loves her or him and how she or he might respond to that love. The person grows in freedom to discern and choose actions or directions of greater value and potential for good. • Honor differences Ignatius valued differences in relation to times, culture and each individual. Thus, adaptation to widely varied situations is respected, indeed expected. Ignatian spirituality provides a foundation and framework that can support accommodation to varied settings. • Experiential Ignatius developed a method to experience Ignatian spirituality. He called this method the “Spiritual Exercises.” He and his early companions found that the Spiritual Exercises helped to re-order and re- direct their lives to praise and serve God. Today, people seek to “make the Spiritual Exercises” for variouis reasons: to form a closer relationship with God, to consider vocational or other life choices, to be a better person (e.g., parent, spouse, colleague, neighbor, global citizen) or to more fully understand Ignatian spirituality and Jesuit identity. -

Download PDF Sample Page

Item No: 3005 Introduction to the Devout Life, Leather Hardback 0 1 0 cm in SECOND PART OF THE INTRODUCTION 51 If you will take my advice, you will say your Pater, your Ave 2 3 and the Credo in Latin; but you will also take care to under- 1 stand exactly what the words mean in your mother tongue, so that, whilst saying them in the language of the Church, you may nevertheless relish the admirable and delicious meaning 4 5 of these holy prayers, which you should say, fixing your atten- tion earnestly upon their meaning and stirring up your affec- 2 tions thereby; not hurrying in order to say many of them, but taking care to say from your heart those which you do say; for 6 7 one single Pater said with feeling is worth more than many recited quickly and in haste. e rosary is a very profitable kind of prayer, provided that 3 you understand how to say it properly; and in order to do so, 8 9 provide yourself with one or other of the little books which ex- plain how it should be recited. It is also good to say the litanies of our Lord, of our Lady, and of the Saints, and all the other 10 vocal prayers which are to be found in approved manuals and 4 prayer-books, yet on the understanding that, if you have the gift of mental prayer, you always reserve for that the principal 11 place; so that if after making mental prayer you cannot say any vocal prayers at all, either because of your many occupations, 12 or for some other reason, be not disturbed on that account, but 5 merely say, before or after your meditation, the Lord’s Prayer, 13 the Angelic Salutation, and the Apostles’ Creed. -

Ignatian Spirituality: an Introduction

Ignatian Spirituality: An Introduction Redemptorist Renewal Center Tucson, Arizona Dec. 27, 2015 - Jan. 7, 2016 Professor Matthew Ashley University of Notre Dame Course Description This course will provide an introduction to Ignatian spirituality. Ignatian spirituality draws its strength, on the one hand, from the many ways it brings together trends and themes from the prior history of Christian spirituality. In this sense there is nothing new in it. On the other hand, Ignatius and his first followers were keenly sensitive to the multitude of challenges facing the Church and committed Christian life in the sixteenth century, which in many ways sees the beginning of the transition to our modern world and its many challenges. Thus, their genius lay in configuring the spiritual riches of the past to confront these challenges. Their success is attested by the enduring power and flexibility of this spirituality to serve as a continuing resources to meet the challenges of the current day. We will consider this process of initial configuration and ongoing reconfiguration historically, with particular attention to two foundational documents: The Spiritual Exercises and The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus. Then we will explore its continuing vitality by studying some contemporary figures who interpret and apply it today, including Pope Francis. This draft of the syllabus may be changed to reflect the number of course participants. Course Goals: After having completed this course students will be able to, 1. identify the principal historical events and traditions in Christian spirituality that influenced the lives of Ignatius and his first companions as they formulated their distinctive spirituality and describe how they are present to and interact in the two foundational documents for Ignatian spirituality from the sixteenth century: The Spiritual Exercises and The Constitutions); 2. -

Christian Meditation: Prayer Is Very Different from Eastern Meditation Practices

Don't let the word "meditation" fool you. Mental Christian Meditation: prayer is very different from Eastern meditation practices. A Beginner's Guide to Non-Christian meditation practices aim at emptying the mind. Catholic Mental Prayer Christian meditation engages the mind in prayer. Source: http://www.beginningcatholic.com/how-to-pray.html Catholic meditation seeks use the faculties of the Christian meditation "engages thought, mind to know the Lord, understand his love for imagination, emotion, and desire" in prayer. us, and to move into deep union with him. Use of (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2708) the mind "is necessary in order to deepen our convictions of faith, prompt the conversion of our It is also known as mental prayer. heart, and strengthen our will to follow Christ." (Catechism, 2708) This article is a detailed, "how to" guide to Christian meditation. You can develop a strong Put simply, our goal is to to answer the basic prayer life! human question: "Lord, what do you want me to do?" (Catechism, 2706) Christian meditation is Christian meditation must immerse us in the essential Trinity: we surrender ourselves to the Holy Spirit, the master of prayer, so that he can unite us to Every Christian needs to practice mental prayer. Christ and perfect our prayer to the Father. Every day. "Because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of Your faith cannot live without prayer, the "vital his Son into our hearts, crying, 'Abba! Father!'" and personal relationship with the living and true God." (Catechism, 2744 & 2558) (Gal 4:6) Recall the basic truths about prayer from this (If you want to know more about the differences between non- Christian and Christian meditation, the Vatican's Congregation for site's how to pray article: the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) wrote a paper on the topic. -

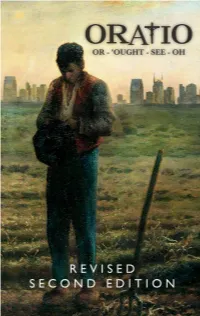

Oratio-Sample.Pdf

REVISED SECOND EDITION RHYTHMS OF PRAYER FROM THE HEART OF THE CHURCH DILLON E. BARKER JIMMY MITCHELL EDITORS ORATIO (REVISED SECOND EDITION) © 2017 Dillon E. Barker & Jimmy Mitchell. First edition © 2011. Second edition © 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-692-89224-4 Published by Mysterium LLC Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. LoveGoodCulture.com NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Jayd D. Neely Censor Librorum IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. David R. Choby Bishop of Nashville May 9, 2017 For bulk orders or group rates, email [email protected]. Special thanks to Jacob Green and David Lee for their contributions to this edition. Excerpts taken from Handbook of Prayers (6th American edition) Edited by the Rev. James Socias © 2007, the Rev. James Socias Psalms reprinted from The Psalms: A New Translation © 1963, The Grail, England, GIA Publications, Inc., exclusive North American agent, www.giamusic.com. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the Revised Standard Version Bible, Second Catholic Edition © 2000 & 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Rites of the Catholic Church © 1990, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Book of Blessings © 1988, 1990, USCCB & ICEL. All rights reserved. All ritual texts of the Catholic Church not already mentioned are © USCCB & ICEL. Cover art & design by Adam Lindenau adapted from “The Angelus” by Jean-François Millet, 1857 The Tradition of the Church proposes to the faithful certain rhythms of praying intended to nourish continual prayer. Some are daily, such as morning and evening prayer, grace before and after meals, the Liturgy of the Hours. -

February 28, 2021 Second Sunday of Lent

DIVINE MERCY PARISH Sunday, February 28, 2021 Second Sunday of lent Epiphany Church Saint Mary of Mercy Church 184 Washington Place 202 Stanwix St Pittsburgh PA 15219 Pittsburgh PA 15222 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE Mass Intentions 164 Washington Place Pittsburgh, PA 15219 To request a Mass intention, please call www.divinemercypgh.org [email protected] or email the Parish Office at 412-471-0257 [email protected] or visit divinemercypgh.org to complete an online form. CLERGY TEAM PARISH STAFF Join our Parish Family Pastor Coordinator of Communication Visit our website at Reverend Christopher D. Donley And Special Events www.divinemercypgh.org or call the [email protected] Renée Driscoll parish office. [email protected] Deacon Samuel Toney Director of Operations Prayer Requests [email protected] Charles Goetz If you would like to be added to our [email protected] Deacon Candidate prayer request board please contact (Our Lady of Mt. Carmel) Music Minister/Director of Liturgy the office or email John P. Corcoran Matthew Radican [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Bulletin Requests In Residence Office Manager Reverend Edward Bryce Cynthia Goetz If you would like to have information Reverend Edward Muge [email protected] included in the bulletin, please contact Reverend Augustine Wayii the Parish Office at Wedding Coordinator [email protected]. Seminarians Renew the ‘I do’ Dolores Shipe Xavier Engle [email protected] Schedule a Meeting [email protected]