Monet January 22 – May 28, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monet and American Impressionism

Harn Museum of Art Educator Resource Monet & Impressionism About the Artist Claude Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840. He enjoyed drawing lessons in school and began making and selling caricatures at age seventeen. In 1858, he met landscape artist Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) who introduced him to plein-air (outdoor) painting. During the 1860s, only a few of Monet’s paintings were accepted for exhibition in the prestigious annual exhibitions known as the Salons. This rejection led him to join with other Claude Monet, 1899 artists to form an independent group, later known as the Impressionists. Photo by Nadar During the 1860s and 1870s, Monet developed his technique of using broken, rhythmic brushstrokes of pure color to represent atmosphere, light and visual effects while depicting his immediate surroundings in Paris and nearby villages. During the next decade, his fortune began to improve as a result of a growing base of support from art dealers and collectors, both in Europe and the United States. By the mid-1880s, his paintings began to receive critical “Everyone discusses my acclaim. art and pretends to understand, as if it were By 1890, Monet was financially secure enough to purchase a house in Giverny, a rural town in Normandy. During these later years, Monet began painting the same subject over and over necessary to understand, again at different times of the day or year. These series paintings became some of his most when it is simply famous works and include views of the Siene River, the Thames River in London, Rouen necessary to love.” Cathedral, oat fields, haystacks and water lilies. -

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Caroline Mc Corriston Claude Monet (1840-1926) ● Monet was the leading figure of the impressionist group. ● As a teenager in Normandy he was brought to paint outdoors by the talented painter Eugéne Boudin. Boudin taught him how to use oil paints. ● Monet was constantly in financial difficulty. His paintings were rejected by the Salon and critics attacked his work. ● Monet went to Paris in 1859. He befriended the artists Cézanne and Pissarro at the Academie Suisse. (an open studio were models were supplied to draw from and artists paid a small fee).He also met Courbet and Manet who both encouraged him. ● He studied briefly in the teaching studio of the academic history painter Charles Gleyre. Here he met Renoir and Sisley and painted with them near Barbizon. ● Every evening after leaving their studies, the students went to the Cafe Guerbois, where they met other young artists like Cezanne and Degas and engaged in lively discussions on art. ● Monet liked Japanese woodblock prints and was influenced by their strong colours. He built a Japanese bridge at his home in Giverny. Monet and Impressionism ● In the late 1860s Monet and Renoir painted together along the Seine at Argenteuil and established what became known as the Impressionist style. ● Monet valued spontaneity in painting and rejected the academic Salon painters’ strict formulae for shading, geometrically balanced compositions and linear perspective. ● Monet remained true to the impressionist style but went beyond its focus on plein air painting and in the 1890s began to finish most of his work in the studio. Personal Style and Technique ● Use of pure primary colours (straight from the tube) where possible ● Avoidance of black ● Addition of unexpected touches of primary colours to shadows ● Capturing the effect of sunlight ● Loose brushstrokes Subject Matter ● Monet painted simple outdoor scenes in the city, along the coast, on the banks of the Seine and in the countryside. -

Claude Monet

I make no other wish than to be more closely involved with nature, and I covet no other fate than to have . worked and lived in harmony with her laws.” — Claude Monet By 1913 Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926) had secured the death of his eldest son, Jean, in 1914; and the his position as the most successful living painter in France. international trauma of World War I. The work Monet This exhibition focuses primarily on the period between produced during this period is also marked by his 1913 and 1926, when the well-traveled Monet devoted struggle with cataracts: first diagnosed in 1912, all of his creative attention to a single location—his he eventually underwent an operation in 1923. home and gardens in Giverny, some forty-five miles northwest of Paris. There he created an environment In the final chapter of his life and career, Monet completely under his control. With its evolving scenery remained fiercely ambitious in his approach to painting. of flower beds, footpaths, bridges, willows, wisteria, Throughout his seventies and eighties, he transformed and water lilies, the garden became a personal laboratory his technique by enlarging his canvases, experimenting for the artist’s sustained study of natural phenomena. with compositional cropping, and playing with tonal In it Monet found the creative catharsis he needed to harmonies. Boldly balancing representation and persist through a series of personal tragedies, including abstraction, Monet’s radical late works redefine the the death of his second wife, Alice Hoschedé, in 1911; master of Impressionism as a forebear of modernism. Securing Success “Monet is only an eye, but my God, what an eye!” — Paul Cézanne Claude Monet, Alice Hoschedé, and their combined family of eight children settled in Giverny in 1883, taking up residence at the Pressoir (the Cider Press), as their home was affectionately called. -

Monet's Water-Lilied Defense Sarah Bietz

Monet’s Water-Lilied Defense Sarah Bietz Abstract Claude Monet donated many of his water lily triptych paintings to the French government after WWI, leading critics to theorize that his artistic motivation was a patriotic love for his war-torn homeland. This paper explores other theories on Monet’s motivation to create the works. Drawing from the analysis of art historian Tamar Garb in her paper, “Painterly Plentitude,” I will argue that we should not overlook the significance of the water lily series as Monet’s final work. The painter’s health was deteriorating with his increasing age, and yet his last project was his most ambitious. Applying Garb’s thesis to Monet’s final series, it appears that his fascination with painting water, the association he made between water and death, and Monet’s choice of huge canvases all suggest that the paintings were an intensely personal project, rather than patriotic. Key Words: Claude, Monet, waterlily, Impressionism, Giverny, Garb, water, death, France, Camille CLAUDE Monet’s final series of paintings analysis to Monet’s Agapanthus (Figure 2 &3) consumed him. His series of water lily and his series of water lily triptychs, a new paintings, a project that he admitted was “an perspective of Monet’s series is constructed enormous task, above all at my age,” are now a based on his obsession with the appearance of wonder and a mystery to millions of modern water, his association of water with death, and viewers. 1 Critics study their colors, the shocking scale of his final masterpieces. brushstrokes, and compositions, speculating if Monet’s motivation was a response to WWI, a fascination with garden design, a result of his failing eyesight, or the expression of a mentality that belongs in the Narcissus myth.2 A different possibility is born in Tamar Garb’s article, “Painterly Plentitude,” in which she constructs a theory that Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s final painting, The Bathers (Figure 1), was an unconscious defense against the aging painter’s oncoming mortality. -

Fauvism and Expressionism

Level 3 NCEA Art History Fauvism and Expressionism Workbook Pages Fauvism and Expressionism What this is: Acknowledgements These pages are part of a framework for students studying This workbook was made possible: NCEA Level 3 Art History. It is by no means a definitive • by the suggestions of Art History students at Christchurch document, but a work in progress that is intended to sit Girls’ High School, alongside internet resources and all the other things we • in consultation with Diane Dacre normally do in class. • using the layout and printing skills of Chris Brodrick of Unfortunately, illustrations have had to be taken out in Verve Digital, Christchurch order to ensure that copyright is not infringed. Students could download and print their own images by doing a Google image search. While every attempt has been made to reference sources, many of the resources used in this workbook were assembled How to use it: as teaching notes and their original source has been difficult to All tasks and information are geared to the three external find. Should you become aware of any unacknowledged source, Achievement Standards. I have found that repeated use of the please contact me and I will happily rectify the situation. charts reinforces the skills required for the external standards Sylvia Dixon and gives students confidence in using the language. [email protected] It is up to you how you use what is here. You can print pages off as they are, or use the format idea and the templates to create your own pages. More information: You will find pages on: If you find this useful, you might be interested in the full • the Blaue Reiter workbook. -

Claude Monet : Seasons and Moments by William C

Claude Monet : seasons and moments By William C. Seitz Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1960 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Museum: Distributed by Doubleday & Co. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2842 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Seasons and Moments 64 pages, 50 illustrations (9 in color) $ 3.50 ''Mliili ^ 1* " CLAUDE MONET: Seasons and Moments LIBRARY by William C. Seitz Museumof MotfwnArt ARCHIVE Claude Monet was the purest and most characteristic master of Impressionism. The fundamental principle of his art was a new, wholly perceptual observation of the most fleeting aspects of nature — of moving clouds and water, sun and shadow, rain and snow, mist and fog, dawn and sunset. Over a period of almost seventy years, from the late 1850s to his death in 1926, Monet must have pro duced close to 3,000 paintings, the vast majority of which were landscapes, seascapes, and river scenes. As his involvement with nature became more com plete, he turned from general representations of season and light to paint more specific, momentary, and transitory effects of weather and atmosphere. Late in the seventies he began to repeat his subjects at different seasons of the year or moments of the day, and in the nineties this became a regular procedure that resulted in his well-known "series " — Haystacks, Poplars, Cathedrals, Views of the Thames, Water ERRATA Lilies, etc. -

Donna M. Guenther, M.D

Donna M. Guenther, M.D. Solo Exhibitions 2008 Bikram Yoga International Competition, Forgotten Faces of AIDS: India, Los Angeles, CA 2007 Bikram Yoga Studio, World AIDS Day: Forgotten Faces of AIDS, Berkeley, CA 2006 Allegheny College, Forgotten Faces of AIDS: The AIDS Orphans, Meadville, PA Postal History Foundation Museum, Pilgrimage: Tibet in the Year of the Sheep, Tucson, AZ Desa Arts Gallery, Portals, Oakland, CA. Three Dollar Bill Cafe at the LGBT Community Center, Diwali: A Celebration of Light and Shadowed Lives, San Francisco, CA. 2005 5th International Conference on AIDS India, HIV/AIDS Photo Collages, Chennai, India Youthinkwell Publishing, Portraits of Youth, Pasadena, CA. Cantoo Photo Processing Gallery, All God's Children, Berkeley, CA. 1998 Eclipse Salon, Global Visions, Atlanta, GA. 1995 Allegheny College, Small Claims, Large Encounters, Meadville, PA. Group Exhibitions 2007 Denver International Airport, Denver International Invitational Exhibit, Denver, CO. The Center for Fine Art Photography, Abstractions, Fort Collins, CO. 2005 Zaimul Gallery, Institute of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka, Tarantula: A Multidisciplinary Group Exhibition, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Global Arts Village, Forgotten Faces of AIDS: The AIDS Orphans, Gitorni, New Delhi, India. Global Arts Village, Faces of the Buddha, Gitorni, New Delhi, India. Danville Fine Arts Gallery, The Art of Architecture, Danville, CA. Deep Roots Urban Tea House, Love and Revolution, Oakland, CA. Hollis Street Project, Commotion, Emeryville, CA. 2003 Seven Degrees Art Gallery, Through Voyagers Eyes, Laguna Beach, CA. 2002 National Press Club, Through Voyagers Eyes, Washington, D.C. Publications 2009 Vasavya Mahila Mandali, Second Innings, article on the Grannies’ Clubs, June 2009. www.ixalt.com, photographs for website. -

Impressionism and the History of Artists Behind It

Impressionism and the History of Artists behind It Grant Meger 7th December 2018 Abstract This document contains the content of both pages about Claude Monet, Biography and Paintings. Contents Contents i List of Figures ii 1 Biography 1 1.1 Early Years .............................. 1 1.2 Middle Years ............................. 2 1.3 Later Years .............................. 2 2 Paintings 2 2.1 Water Lilies ............................. 2 2.2 The Sea at Le Havre ......................... 3 References 5 i List of Figures 1 Photo of Claude Monet in 1899 ..................... 1 2 Water Lilies ............................... 3 3 The Sea at Le Havre ........................... 4 ii Figure 1: Photo of Claude Monet in 1899 (Tournachon 1899) 1 Biography 1.1 Early Years Oscar-Claude Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840 and moved to the coastal city of Le Havre around age 5. He was fascinated by the nature, sea and changing weather and found inspiration for drawing at a very young age. In high school, Monet studied drawing with Jacques-François Ochard, a local artist, specializing in boats, landscapes, and caricatures. At age 16, Monet’s mother died and his aunt helped support him, but he left school. By 1856, Monet’s caricature drawings went on display in a local frame shop and soon after met Eugène-Louis Boudin, the son of a sailor. Monet traveled with Boudin to Rouelles for painting in the open air, where Monet learned to capture sub- jects quickly. At age 18, Monet went to Paris exploring galleries and studios, and worked at the Académie Suisse. Monet and his fellow students Renoir, Sis- ley and Bazille, from the studio of Charles Gleyre, begin to take the first step into professional status: entering paintings into the Salon to receive money, a long and difficult process. -

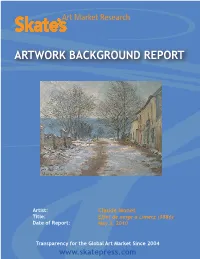

Artwork Background Report

ARTWORK BACKGROUND REPORT Artist: Claude Monet Title: Effet de neige à Limetz (1886) Date of Report: May 3, 2010 Transparency for the Global Art Market Since 2004 www.skatepress.com Contents 1. Artwork Profiled 2 2. Skate’s Investment Summary 3 3. Skate’s Artwork Risk Rang 4 4. Brief Biography of Claude Monet 5 5. Public Collecons 7 6. Solo Exhibions 9 7. Group Exhibions, 2009-2010 10 8. Dealer Directory 11 9. Provenance 12 10. Known Thes of Monet’s Works 13 11. Market for Monet’s Works 14 Top 10 Monet Sales 14 Repeat Sales of Monet’s Works 14 12. Market for Effet de neige à Limetz 15 Peer Group for Effet de neige à Limetz 15 Repeat Sales in Peer Group 16 Peer Group Analysis 17 13. Approach to Art Valuaon 18 14. Skate’s Artwork Risk Scale 18 15. Peer Group Formaon 19 16. Disclaimer 19 Skate’s Art Market Research 575 Broadway, 5th Floor New York, NY 10012 / Tel: +1.212.514.6012 / Fax: +1.212.514.6037 www.skatepress.com Report 9-CM-001 Client 0010 May 3, 2010 1. Artwork Profiled This report has been prepared for the following artwork: Arst: Claude Monet (1840-1926) Title: Effet de neige à Limetz Year: 1886 Medium: Oil on canvas Size: 25½ x 32 in. (65 x 81 cm.) The artwork is listed in the catalogue of the following aucon: Aucon House: Chrise’s Aucon Loca=on: New York Aucon Name: Impressionist/Modern Evening Sale Lot: 61 Aucon Date: Tuesday, May 4, 2010 Aucon Es=mate: $2,500,000 - $3,500,000 Source: Courtesy of Chrise’s. -

Restricting Marketing of Foods and Beverages to Children in Canada

Restricting Marketing of Foods and Beverages to Children in Canada Prospective Economic Impact and Industry Responses March 24, 2015 Outline of Webinar 1. Background 2. Are restrictions effective? 3. Are restrictions cost-effective? 4. Impact on industry 5. Industry response 6. Lessons from tobacco control 2 Background 1. Rapidly increasing levels of obesity in Canadian children 2. Poor health - cardiovascular disease, asthma, gallbladder disease, many cancers, osteoarthritis, chronic back pain, type II diabetes 3 Background 3. Economic burden Ø Excess weight vs. tobacco in Canada in 2012 - $19.0 vs. $21.3 billion (Krueger et al. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2013; 105(1):e69-78) Ø Updated model, excess weight vs. tobacco in Canada in 2013 - $23.3 vs. $18.7 billion (Krueger et al. Canadian Journal of Public Health, under review) 4 Background 4. World Health Organization 2009 “Evidence from many of the more complex studies, capable of inferring causality, demonstrate a statistically significant association between food promotion and children’s knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and health status.” (Cairns et al. The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence to December 2008. 2009. World Health Organization.) 5 Are Restrictions Effective? • Progressive ban in the UK on the advertising and promotion of foods and drinks that are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) to children implemented April 1, 2007 • Children 4-15 exposed to 37% less HFSS advertising in 2009 compared to 2005 Ø Children 4-9 52% Ø Children 10-15 22% 6 Are Restrictions Effective? • RCT in a Quebec children’s camp assessing 5-8 year old children’s afternoon snack choices • 2 weeks of daily exposure to televised food and beverage messages • “Children who viewed candy commercials picked significantly more candy over fruit as snacks. -

University Reporter University Publications and Campus Newsletters

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston 1996-2009, University Reporter University Publications and Campus Newsletters 12-1-2006 University Reporter - Volume 11, Number 04 - December 2006 Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/university_reporter Recommended Citation "University Reporter - Volume 11, Number 04 - December 2006" (2006). 1996-2009, University Reporter. Paper 27. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/university_reporter/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications and Campus Newsletters at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1996-2009, University Reporter by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N E W S A N D I N FORMAT I O N A B O U T T H E U ni VERS I T Y O F M ASSACHUSETTS B OSTO N THE UNIVERSI T Y � ReporterVolume 11, Number 4 December 2006 UMass and Chinese Officials Launch The University of Massachusetts Confucius Institute By Ed Hayward seventh established in the United Graduate College of Education, On November 20, the Univer- States and the first in New Eng- China Program Center, Interna- sity of Massachusetts and China’s land. The institute will provide tional Student Services, and Study Ministry of Education launched programs and services including Abroad Program will contribute the University of Massachusetts teaching the Chinese language, their expertise. Confucius Institute located at the training of Chinese teachers, China plans to create 1,000 UMass Boston, a non-profit pub- curriculum development, and Confucius Institutes worldwide lic institute to promote the teach- cultural events. -

Artist's Portfolio, 2018

A N I TA KO N T R E C > artist’s portfolio www.anitakontrec.com [email protected] © ANITA KONTREC > 1 contentS 3 > concePTUAL WORKS WITH TEXT 12 > SCULPTURES 21 > coLOUR, ENERGY, LIGHT 34 > site-specific installations 42 > hoUSES AND DREAMS 51 > BIOGRAPHY, SELecteD EXHIBITIONS 54 > art CRITICS AND HIStorianS ABOUT anita kontrec WORK © ANITA KONTREC > 2 concePTUAL WORKS WITH TEXT (from mid-80-ies till today) “To Anita Kontrec writing is a means for understand- ing and interpreting the world, as well as a medium that has meaning, a pictorial quality, material and magic significance. letters and ideograms express different layers of meaning which are manifested in paper, plaster, clay, stone, bronze, gold, and synthetic resin. These media have both material presence and immaterial meaning. Kontrec’s pictures with writ- ing /Schriftbilder/ are layered images – palimpsests which display the simultaneity and multiple facets of language, writing and communication.” Peter Lodermeyer, preface to the catalogue Recall Atlantis, 2006. © ANITA KONTREC > 3 “I AM reaDinG the BookS Which haVE not Yet Been Written” RECALL ATLANTIS, KaraS GaLLerY, ZAGreB, 2006 © ANITA KONTREC > 4 “Text, Kontext, Kontrec”, 2006 © ANITA KONTREC > 5 RIGHTWRONG, ArtHELLWEG EDition, SoeST/KÖLN, 1990/2004. © ANITA KONTREC > 6 “notebook – istrian spiral sfumato”, 1980 © ANITA KONTREC > 7 “notebook – istrian spiral sfumato”, 1980 © ANITA KONTREC > 8 “towers of babel”, Zagreb, 2016 © ANITA KONTREC > 9 “warten sie, sie werden platZiert” - installation, leipZig - spinnerei, 2013 © ANITA KONTREC > 10 “calligraphic landscapes” - installation, leipZig - spinnerei, 2013. © ANITA KONTREC > 11 SCULPTURES (from mid-80-ies till today) Regardless of the grade of abstraction, her grey ce- ment sculptures, comprising the whole potential of possible associations, are still very close to natural, living forms.