Quark Phases in Neutron Stars and a “Third Family” of Compact Stars As a Signature for Phase Transitions∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Pulsars

High-energy astrophysics Explore the PUL SAR menagerie Astronomers are discovering many strange properties of compact stellar objects called pulsars. Here’s how they fit together. by Victoria M. Kaspi f you browse through an astronomy book published 25 years ago, you’d likely assume that astronomers understood extremely dense objects called neutron stars fairly well. The spectacular Crab Nebula’s central body has been a “poster child” for these objects for years. This specific neutron star is a pulsar that I rotates roughly 30 times per second, emitting regular appar- ent pulsations in Earth’s direction through a sort of “light- house” effect as the star rotates. While these textbook descriptions aren’t incorrect, research over roughly the past decade has shown that the picture they portray is fundamentally incomplete. Astrono- mers know that the simple scenario where neutron stars are all born “Crab-like” is not true. Experts in the field could not have imagined the variety of neutron stars they’ve recently observed. We’ve found that bizarre objects repre- sent a significant fraction of the neutron star population. With names like magnetars, anomalous X-ray pulsars, soft gamma repeaters, rotating radio transients, and compact Long the pulsar poster child, central objects, these bodies bear properties radically differ- the Crab Nebula’s central object is a fast-spinning neutron star ent from those of the Crab pulsar. Just how large a fraction that emits jets of radiation at its they represent is still hotly debated, but it’s at least 10 per- magnetic axis. Astronomers cent and maybe even the majority. -

Neutron Stars

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide Neutron Stars Ordinary matter, or the stuff we and everything around us is made of, consists largely of empty space. Even a rock is mostly empty space. This is because matter is made of atoms. An atom is a cloud of electrons orbiting around a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons. The nucleus contains more than 99.9 percent of the mass of an atom, yet it has a diameter of only 1/100,000 that of the electron cloud. The electrons themselves take up little space, but the pattern of their orbit defines the size of the atom, which is therefore 99.9999999999999% Chandra Image of Vela Pulsar open space! (NASA/PSU/G.Pavlov et al. What we perceive as painfully solid when we bump against a rock is really a hurly-burly of electrons moving through empty space so fast that we can't see—or feel—the emptiness. What would matter look like if it weren't empty, if we could crush the electron cloud down to the size of the nucleus? Suppose we could generate a force strong enough to crush all the emptiness out of a rock roughly the size of a football stadium. The rock would be squeezed down to the size of a grain of sand and would still weigh 4 million tons! Such extreme forces occur in nature when the central part of a massive star collapses to form a neutron star. The atoms are crushed completely, and the electrons are jammed inside the protons to form a star composed almost entirely of neutrons. -

R-Process Elements from Magnetorotational Hypernovae

r-Process elements from magnetorotational hypernovae D. Yong1,2*, C. Kobayashi3,2, G. S. Da Costa1,2, M. S. Bessell1, A. Chiti4, A. Frebel4, K. Lind5, A. D. Mackey1,2, T. Nordlander1,2, M. Asplund6, A. R. Casey7,2, A. F. Marino8, S. J. Murphy9,1 & B. P. Schmidt1 1Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), Australia 3Centre for Astrophysics Research, Department of Physics, Astronomy and Mathematics, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, AL10 9AB, UK 4Department of Physics and Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 5Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Center, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 6Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 7School of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University, VIC 3800, Australia 8Istituto NaZionale di Astrofisica - Osservatorio Astronomico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi, 5, 50125, Firenze, Italy 9School of Science, The University of New South Wales, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia Neutron-star mergers were recently confirmed as sites of rapid-neutron-capture (r-process) nucleosynthesis1–3. However, in Galactic chemical evolution models, neutron-star mergers alone cannot reproduce the observed element abundance patterns of extremely metal-poor stars, which indicates the existence of other sites of r-process nucleosynthesis4–6. These sites may be investigated by studying the element abundance patterns of chemically primitive stars in the halo of the Milky Way, because these objects retain the nucleosynthetic signatures of the earliest generation of stars7–13. -

Magnetars: Explosive Neutron Stars with Extreme Magnetic Fields

Magnetars: explosive neutron stars with extreme magnetic fields Nanda Rea Institute of Space Sciences, CSIC-IEEC, Barcelona 1 How magnetars are discovered? Soft Gamma Repeaters Bright X-ray pulsars with 0.5-10keV spectra modelled by a thermal plus a non-thermal component Anomalous X-ray Pulsars Bright X-ray transients! Transients No more distinction between Anomalous X-ray Pulsars, Soft Gamma Repeaters, and transient magnetars: all showing all kind of magnetars-like activity. Nanda Rea CSIC-IEEC Magnetars general properties 33 36 Swift-XRT COMPTEL • X-ray pulsars Lx ~ 10 -10 erg/s INTEGRAL • strong soft and hard X-ray emission Fermi-LAT • short X/gamma-ray flares and long outbursts (Kuiper et al. 2004; Abdo et al. 2010) • pulsed fractions ranging from ~2-80 % • rotating with periods of ~0.3-12s • period derivatives of ~10-14-10-11 s/s • magnetic fields of ~1013-1015 Gauss (Israel et al. 2010) • glitches and timing noise (Camilo et al. 2006) • faint infrared/optical emission (K~20; sometimes pulsed and transient) • transient radio pulsed emission (see Woods & Thompson 2006, Mereghetti 2008, Rea & Esposito 2011 for a review) Nanda Rea CSIC-IEEC How magnetar persistent emission is believed to work? • Magnetars have magnetic fields twisted up, inside and outside the star. • The surface of a young magnetar is so hot that it glows brightly in X-rays. • Magnetar magnetospheres are filled by charged particles trapped in the twisted field lines, interacting with the surface thermal emission through resonant cyclotron scattering. (Thompson, Lyutikov & Kulkarni 2002; Fernandez & Thompson 2008; Nobili, Turolla & Zane 2008a,b; Rea et al. -

Stellar Death: White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars, and Black Holes

Stellar death: White dwarfs, Neutron stars & Black Holes Content Expectaions What happens when fusion stops? Stars are in balance (hydrostatic equilibrium) by radiation pushing outwards and gravity pulling in What will happen once fusion stops? The core of the star collapses spectacularly, leaving behind a dead star (compact object) What is left depends on the mass of the original star: <8 M⦿: white dwarf 8 M⦿ < M < 20 M⦿: neutron star > 20 M⦿: black hole Forming a white dwarf Powerful wind pushes ejects outer layers of star forming a planetary nebula, and exposing the small, dense core (white dwarf) The core is about the radius of Earth Very hot when formed, but no source of energy – will slowly fade away Prevented from collapsing by degenerate electron gas (stiff as a solid) Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE RING NEBULA Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE CAT’S EYE NEBULA Death of massive stars When the core of a massive star collapses, it can overcome electron degeneracy Huge amount of energy BAADE ZWICKY released - big supernova explosion Neutron star: collapse halted by neutron degeneracy (1934: Baade & Zwicky) Black Hole: star so massive, collapse cannot be halted SN1006 1967: Pulsars discovered! Jocelyn Bell and her supervisor Antony Hewish studying radio signals from quasars Discovered recurrent signal every 1.337 seconds! Nicknamed LGM-1 now called PSR B1919+21 BRIGHTNESS TIME NATURE, FEBRUARY 1968 1967: Pulsars discovered! Beams of radiation from spinning neutron star Like a lighthouse Neutron -

Probing the Nuclear Equation of State from the Existence of a 2.6 M Neutron Star: the GW190814 Puzzle

S S symmetry Article Probing the Nuclear Equation of State from the Existence of a ∼2.6 M Neutron Star: The GW190814 Puzzle Alkiviadis Kanakis-Pegios †,‡ , Polychronis S. Koliogiannis ∗,†,‡ and Charalampos C. Moustakidis †,‡ Department of Theoretical Physics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] (A.K.P.); [email protected] (C.C.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Current address: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece. ‡ These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: On 14 August 2019, the LIGO/Virgo collaboration observed a compact object with mass +0.08 2.59 0.09 M , as a component of a system where the main companion was a black hole with mass ∼ − 23 M . A scientific debate initiated concerning the identification of the low mass component, as ∼ it falls into the neutron star–black hole mass gap. The understanding of the nature of GW190814 event will offer rich information concerning open issues, the speed of sound and the possible phase transition into other degrees of freedom. In the present work, we made an effort to probe the nuclear equation of state along with the GW190814 event. Firstly, we examine possible constraints on the nuclear equation of state inferred from the consideration that the low mass companion is a slow or rapidly rotating neutron star. In this case, the role of the upper bounds on the speed of sound is revealed, in connection with the dense nuclear matter properties. Secondly, we systematically study the tidal deformability of a possible high mass candidate existing as an individual star or as a component one in a binary neutron star system. -

Neutron Stars & Black Holes

Introduction ? Recall that White Dwarfs are the second most common type of star. ? They are the remains of medium-sized stars - hydrogen fused to helium Neutron Stars - failed to ignite carbon - drove away their envelopes to from planetary nebulae & - collapsed and cooled to form White Dwarfs ? The more massive a White Dwarf, the smaller its radius Black Holes ? Stars more massive than the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.4 solar masses cannot be White Dwarfs Formation of Neutron Stars As the core of a massive star (residual mass greater than 1.4 ?Supernova 1987A solar masses) begins to collapse: (arrow) in the Large - density quickly reaches that of a white dwarf Magellanic Cloud was - but weight is too great to be supported by degenerate the first supernova electrons visible to the naked eye - collapse of core continues; atomic nuclei are broken apart since 1604. by gamma rays - Almost instantaneously, the increasing density forces freed electrons to absorb electrons to form neutrons - the star blasts away in a supernova explosion leaving behind a neutron star. Properties of Neutron Stars Crab Nebula ? Neutrons stars predicted to have a radius of about 10 km ? In CE 1054, Chinese and a density of 1014 g/cm3 . astronomers saw a ? This density is about the same as the nucleus supernova ? A sugar-cube-sized lump of this material would weigh 100 ? Pulsar is at center (arrow) million tons ? It is very energetic; pulses ? The mass of a neutron star cannot be more than 2-3 solar are detectable at visual masses wavelengths ? Neutron stars are predicted to rotate very fast, to be very ? Inset image taken by hot, and have a strong magnetic field. -

Blasts from the Past Historic Supernovas

BLASTS from the PAST: Historic Supernovas 185 386 393 1006 1054 1181 1572 1604 1680 RCW 86 G11.2-0.3 G347.3-0.5 SN 1006 Crab Nebula 3C58 Tycho’s SNR Kepler’s SNR Cassiopeia A Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European? Arabic, European Arabic, Native American? Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Probable Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Distance Estimate: 8,200 light years Distance Estimate: 16,000 light years Distance Estimate: 3,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,500 light years Distance Estimate: 13,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,000 light years Distance Estimate: 6,000 light years Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Core collapse of massive star NASA’s ChANdrA X-rAy ObServAtOry historic supernovas chandra x-ray observatory Every 50 years or so, a star in our Since supernovas are relatively rare events in the Milky historic supernovas that occurred in our galaxy. Eight of the trine of the incorruptibility of the stars, and set the stage for observed around 1671 AD. -

Neutron(Stars(( Degenerate(Compact(Objects(

Neutron(Stars(( Accre.ng(Compact(Objects6(( see(Chapters(13(and(14(in(Longair((( Degenerate(Compact(Objects( • The(determina.on(of(the( internal(structures(of(white( dwarfs(and(neutron(stars( depends(upon(detailed( knowledge(of(the(equa.on(of( state(of(the(degenerate( electron(and(neutron(gases( Degneracy(and(All(That6(Longair(pg(395(sec(13.2.1%( • In(white&dwarfs,(internal(pressure(support(is(provided(by(electron( degeneracy(pressure(and(their(masses(are(roughly(the(mass(of(the( Sun(or(less( • the(density(at(which(degeneracy(occurs(in(the(non6rela.vis.c(limit(is( propor.onal(to(T&3/2( • This(is(a(quantum(effect:(Heisenberg(uncertainty(says(that δpδx>h/2π# • Thus(when(things(are(squeezed(together(and(δx(gets(smaller((the( momentum,(p,(increases,(par.cles(move(faster(and(thus(have(more( pressure( • (Consider(a(box6(with(a(number(density,n,(of(par.cles(are(hiSng(the( wall;the(number(of(par.cles(hiSng(the(wall(per(unit(.me(and(area(is( 1/2nv(( • the(momentum(per(unit(.me(and(unit(area((Pressure)(transferred(to( the(wall(is(2nvp;(P~nvp=(n/m)p2((m(is(mass(of(par.cle)( Degeneracy6(con.nued( • The(average(distance(between(par.cles(is(the(cube(root(of(the( number(density(and(if(the(momentum(is(calculated(from(the( Uncertainty(principle(p~h/(2πδx)~hn1/3# • and(thus(P=h2n5/3/m6(if(we(define(ma[er(density(as(ρ=[n/m](then( • (P~(ρ5/3(%independent%of%temperature%% • Dimensional(analysis(gives(the(central(pressure(as%P~GM2/r4( • If(we(equate(these(we(get(r~M61/3(e.q%a%degenerate%star%gets%smaller% as%it%gets%more%massive%% • At(higher(densi.es(the(material(gets('rela.vis.c'(e.g.(the(veloci.es( -

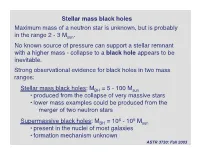

Stellar Mass Black Holes Maximum Mass of a Neutron Star Is Unknown, but Is Probably in the Range 2 - 3 Msun

Stellar mass black holes Maximum mass of a neutron star is unknown, but is probably in the range 2 - 3 Msun. No known source of pressure can support a stellar remnant with a higher mass - collapse to a black hole appears to be inevitable. Strong observational evidence for black holes in two mass ranges: Stellar mass black holes: MBH = 5 - 100 Msun • produced from the collapse of very massive stars • lower mass examples could be produced from the merger of two neutron stars 6 9 Supermassive black holes: MBH = 10 - 10 Msun • present in the nuclei of most galaxies • formation mechanism unknown ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Other types of black hole could exist too: 3 Intermediate mass black holes: MBH ~ 10 Msun • evidence for the existence of these from very luminous X-ray sources in external galaxies (L >> LEdd for a stellar mass black hole). • `more likely than not’ to exist, but still debatable Primordial black holes • formed in the early Universe • not ruled out, but there is no observational evidence and best guess is that conditions in the early Universe did not favor formation. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Basic properties of black holes Black holes are solutions to Einstein’s equations of General Relativity. Numerous theorems have been proved about them, including, most importantly: The `No-hair’ theorem A stationary black hole is uniquely characterized by its: • Mass M Conserved • Angular momentum J quantities • Charge Q Remarkable result: Black holes completely `forget’ how they were made - from stellar collapse, merger of two existing black holes etc etc… Only applies at late times. -

Magnetars: Pion Condensates in the Sky?

Magnetars: Pion Condensates in the Sky? N.D. Hari Dass TIFR-TCIS, Hyderabad In collaboration with V. Soni(Jamia) & Dipankar Bhattacharya(IUCAA) IWARA 2018, Ollantaytambo, Peru. N.D. Hari Dass Magnetars & Pion Condensates Some References N.D. Hari Dass and V. Soni, Mon. Not. Royal Astron. Soc., 425, 1558-1566 (2012). H.B. Nielsen and V. Soni, Phys. Lett. B726, 41-44 (2013). N.D. Hari Dass Magnetars & Pion Condensates Neutron Stars Nuclear density ρ 2:8 1014gm=cm3. Equivalently 0 ' n 0:17nucleons=fermi3. 0 ' Stable neutron stars can have masses in the range 0.1 solar mass to 2 solar masses. Most observed pulsars have masses about 1.4 solar masses. Neutron stars produced in core collapse are expected with this mass. Heavier neutron stars are believed to be as a result of acretion later on. Typical radii of NS are 10 - 20 kms. Neutron stars can be thought of as giant nuclei with A 1057! ' N.D. Hari Dass Magnetars & Pion Condensates Neutron Star Structure Density ρ decreases as one moves outwards from the centre. The outer kilometre or so is the Crust. It consists of a lattice of bare nuclei and a degenerate electron gas. Next to the crust is a superfluid layer and vortices here contribute to the angular momentum of the star. These vortices also play an important role in the so called glitches whence the star actually speeds up. The least understood part is the core of the NS. Density here can be in the range of 3-10 times nuclear density. It is also very hot. -

![Arxiv:1607.03593V1 [Gr-Qc] 13 Jul 2016 Hc Ssilukona Ula N H Super-Nuclear the to and Core, Nuclear Used Densities](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4150/arxiv-1607-03593v1-gr-qc-13-jul-2016-hc-ssilukona-ula-n-h-super-nuclear-the-to-and-core-nuclear-used-densities-1714150.webp)

Arxiv:1607.03593V1 [Gr-Qc] 13 Jul 2016 Hc Ssilukona Ula N H Super-Nuclear the to and Core, Nuclear Used Densities

Tidal deformability and I-Love-Q relations for gravastars with polytropic thin shells 1,2 3 † 4,5‡ Nami Uchikata ,∗ Shijun Yoshida , and Paolo Pani 1Department of Physics, Rikkyo University, Nishi-ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 171-8501, Japan 2Department of Mathematics and Physics, Graduate School of Science, Osaka City University, Sumiyoshi-ku, Osaka 558-8585, Japan 3Astronomical Institute, Tohoku University, Aramaki-Aoba, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8578, Japan 4Dipartimento di Fisica, ”Sapienza” Universit`adi Roma & Sezione INFN Roma1, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Roma, Italy 5Centro Multidisciplinar de Astrof´ısica — CENTRA, Departamento de F´ısica, Instituto Superior T´ecnico — IST, Universidade de Lisboa - UL, Av. Rovisco Pais 1, 1049-001 Lisboa, Portugal (Dated: July 14, 2016) The moment of inertia, the spin-induced quadrupole moment, and the tidal Love number of neutron-star and quark-star models are related through some relations which depend only mildly on the stellar equation of state. These “I-Love-Q” relations have important implications for astro- physics and gravitational-wave astronomy. An interesting problem is whether similar relations hold for other compact objects and how they approach the black-hole limit. To answer these questions, here we investigate the deformation properties of a large class of thin-shell gravastars, which are exotic compact objects that do not possess an event horizon nor a spacetime singularity. Working in a small-spin and small-tidal field expansion, we calculate the moment of inertia, the quadrupole moment, and the (quadrupolar electric) tidal Love number of gravastars with a polytropic thin shell. The I-Love-Q relations of a thin-shell gravastar are drastically different from those of an ordinary neu- tron star.