CO2 Hydrogenation to Formate and Methanol As an Alternative to Photo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phosphine and Ammonia Photochemistry in Jupiter's

40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2009) 1201.pdf PHOSPHINE AND AMMONIA PHOTOCHEMISTRY IN JUPITER’S TROPOSPHERE. C. Visscher1, A. D. Sperier2, J. I. Moses1, and T.C. Keane3. 1Lunar and Planetary Institute, USRA, 3600 Bay Area Blvd., Houston, TX 77058-1113 2Baylor University, Waco, TX 76798, 3Department of Chemistry and Physics, The Sage Colleges, Troy, NY 12180, ([email protected], [email protected]) Introduction: The last comprehensive photo- tions involving the amino radical (NH2) play a larger chemical model for Jupiter’s troposphere was pre- role. We note that this is the first photochemical sented by Edgington et al. [1,2], based upon the work model to include P2H as an intermediate species in PH3 of Atreya et al. [3] and Kaye and Strobel [4-6]. Since photolysis. The equivalent N2Hx species are believed these early studies, numerous laboratory experiments to be important in the combustion chemistry of nitro- have led to an improvement in our understanding of gen compounds [15]. PH3, NH3-PH3, and NH3-C2H2 photochemistry [7-13]. Furthermore, recent Galileo, Cassini, and Earth-based observations have better defined the abundance of key atmospheric constituents as a function of altitude and latitude in Jupiter’s troposphere. These new results provide an opportunity to test and improve theoretical models of Jovian atmospheric chemistry. We have therefore developed a photochemical model for Jupi- ter’s troposphere considering the updated experimental and observational constraints. Using the Caltech/JPL KINETICS code [14] for our photochemical models, our basic approach is two- fold. The validity of our selected chemical reaction list is first tested by simulating the laboratory experiments of PH3, NH3-PH3, and NH3-C2H2 photolysis with pho- tochemical “box” models. -

Zn-Al Mixed Oxides Decorated with Potassium As Catalysts for HT-WGS: Preparation and Properties

catalysts Article Zn-Al Mixed Oxides Decorated with Potassium as Catalysts for HT-WGS: Preparation and Properties Katarzyna Antoniak-Jurak * , Paweł Kowalik, Kamila Michalska, Wiesław Próchniak and Robert Bicki Łukasiewicz Research Network—New Chemical Syntheses Institute, Al. Tysi ˛acleciaPa´nstwa Polskiego 13A, 24-110 Puławy, Poland; [email protected] (P.K.); [email protected] (K.M.); [email protected] (W.P.); [email protected] (R.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-8-1473-1754 Received: 8 September 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: A set of ex-ZnAl-LDHs catalysts with a molar ratio of Zn/Al in the range of 0.3–1.0 was prepared using co-precipitation and thermal treatment. The samples were characterized using various methods, including X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy FT-IR, N2 adsorption, Temperature-programmed desorption of CO2 (TPD-CO2) as well as Scanning electron microscopy (SEM-EDS). Catalyst activity and long-term stability measurements were carried out in a high-temperature water–gas shift (HT-WGS) reaction. Mixed oxide catalysts with various Zn/Al molar ratios decorated with potassium showed high activity in the HT-WGS reaction within the temperature range of 330–400 ◦C. The highest activity was found for the Zn/Al molar ratio of 0.5 corresponding to spinel stoichiometry. However, the catalyst with a stoichiometric spinel molar ratio of Zn/Al (ZnAl_0.5_K) revealed a higher tendency for surface migration and/or vaporization of potassium during overheating at 450 ◦C. -

Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21St Century

Opportunities for Catalysis in The 21st Century A Report from the Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee BASIC ENERGY SCIENCES ADVISORY COMMITTEE SUBPANEL WORKSHOP REPORT Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21st Century May 14-16, 2002 Workshop Chair Professor J. M. White University of Texas Writing Group Chair Professor John Bercaw California Institute of Technology This page is intentionally left blank. Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................... v A Grand Challenge....................................................................................................... v The Present Opportunity .............................................................................................. v The Importance of Catalysis Science to DOE.............................................................. vi A Recommendation for Increased Federal Investment in Catalysis Research............. vi I. Introduction................................................................................................ 1 A. Background, Structure, and Organization of the Workshop .................................. 1 B. Recent Advances in Experimental and Theoretical Methods ................................ 1 C. The Grand Challenge ............................................................................................. 2 D. Enabling Approaches for Progress in Catalysis ..................................................... 3 E. Consensus Observations and Recommendations.................................................. -

'New Insights on the Selective Oxidation of Methanol to Formaldehyde on Femo Based Catalysts'

‘New Insights on the Selective Oxidation of Methanol to Formaldehyde on FeMo Based Catalysts' Catherine Brookes School of Chemistry Cardiff University Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy i This thesis was submitted for examination in August 2015. ii Abstract The selective oxidation of methanol has been studied in detail, with particular focus on gaining insights into the surface active sights responsible for directing the selectivity to formaldehyde. Various Fe and Mo containing oxides have been investigated for their reactivity with methanol, to gain an understanding of the different roles of these components in the industrial catalyst employed, which is a mixed phase comprised of MoO 3 and Fe 2(MoO 4)3. Catalysts have primarily been tested through using TPD (temperature programmed desorption) and TPPFR (temperature programmed pulsed flow reaction). The reactivity of Fe 2O3 is dominated by combustion products, with CO 2 and H 2 produced via a formate intermediate adsorbing at the catalyst surface. For MoO 3 however, the surface is populated by methoxy intermediates, so that the selectivity is almost 100 % directed to formaldehyde. When a mixture of isolated Fe and Mo sites co-exist, the surface methoxy becomes stabilised, resulting in a dehydrogenation reaction to CO and H 2. CO and CO 2 can also be observed on Mo rich surfaces, however here a consequence of the further oxidation of formaldehyde, through a linear pathway. TPD and DRIFTS identify these intermediates and products forming. Since the structure of the industrial catalyst is relatively complex, in that it contains both MoO 3 and Fe 2(MoO 4)3, it is difficult to identify the active site for the reaction with methanol. -

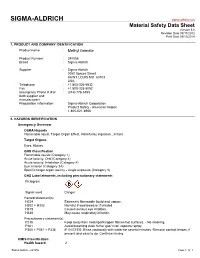

Methyl Formate

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 09/17/2012 Print Date 03/13/2014 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : Methyl formate Product Number : 291056 Brand : Sigma-Aldrich Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards Flammable liquid, Target Organ Effect, Harmful by ingestion., Irritant Target Organs Eyes, Kidney GHS Classification Flammable liquids (Category 1) Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 4) Acute toxicity, Inhalation (Category 4) Eye irritation (Category 2A) Specific target organ toxicity - single exposure (Category 3) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H224 Extremely flammable liquid and vapour. H302 + H332 Harmful if swallowed or if inhaled H319 Causes serious eye irritation. H335 May cause respiratory irritation. Precautionary statement(s) P210 Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. P261 Avoid breathing dust/ fume/ gas/ mist/ vapours/ spray. P305 + P351 + P338 IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 2 Sigma-Aldrich - 291056 Page 1 of 7 Chronic Health Hazard: * Flammability: 4 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 2 Fire: 4 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. Causes respiratory tract irritation. Skin Harmful if absorbed through skin. -

Direct Synthesis of Dimethyl Ether from Syngas on Bifunctional Hybrid

catalysts Article Direct Synthesis of Dimethyl Ether from Syngas on Bifunctional Hybrid Catalysts Based on Supported H3PW12O40 and Cu-ZnO(Al): Effect of Heteropolyacid Loading on Hybrid Structure and Catalytic Activity Elena Millán , Noelia Mota, Rut Guil-López, Bárbara Pawelec , José L. García Fierro and Rufino M. Navarro * Instituto de Catálisis y Petroleoquímica (CSIC), C/Marie Curie 2, Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (R.G.-L.); [email protected] (B.P.); jlgfi[email protected] (J.L.G.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 17 September 2020 Abstract: The performance of bifunctional hybrid catalysts based on phosphotungstic acid (H3PW12O40, HPW) supported on TiO2 combined with Cu-ZnO(Al) catalyst in the direct synthesis of dimethyl ether (DME) from syngas has been investigated. We studied the effect of the HPW loading on TiO2 (from 1.4 to 2.7 monolayers) on the dispersion and acid characteristics of the HPW clusters. When the concentration of the heteropoliacid is slightly higher than the monolayer (1.4 monolayers) the acidity of the clusters is perturbed by the surface of titania, while for concentration higher than 1.7 monolayers results in the formation of three-dimensional HPW nanocrystals with acidity similar to the bulk heteropolyacid. Physical hybridization of supported heteropolyacids with the Cu-ZnO(Al) catalyst modifies both the acid characteristics of the supported heteropolyacids and the copper surface area of the Cu-ZnO(Al) catalyst. -

Platinum Metals Industrial Catalysts Catalysis of Organic Reactions EDITED by M

Platinum Metals Industrial Catalysts Catalysis of Organic Reactions EDITED BY M. G. SCAROS AND M. L. PRUNIER, Marcel Dekker, New York, 1995, 599 pages, ISBN 0-8247-9364-1, U.S. $195.00 This book comprises a set of papers presented reactant purity, agitation and poisons are at the 15th Conference on Catalysis of Organic considered. This is followed by a paper detail- Reactions, held in Phoenix, Arizona, in May ing noble metal recovery operations and the var- 1994. It covers a variety of topics, such as het- ious steps involved in the noble metal “loop”. erogeneous catalysis, asymmetric hydrogena- Heterogeneous catalysis in organic synthesis tion, hydrogenation, oxidation, hydroformyla- is discussed by R. L. Augustine and colleagues tion, catalyst design and catalyst characterisation. from Seton Hall University, New Jersey. This One topic which is emphasised is hydrogena- is illustrated by the platinum catalysed oxida- tion (alpha to omega), and this is intended to tion of alcohols, carbon-carbon bond forming allow a better understanding of the entire reactions of supported palladium catalysts for process, from choosing a catalyst to the noble the Heck type arylation of allylic groups, and metal “loop”. There are over 60 papers and 186 by enantioselective heterogeneous catalysis, contributors, with a healthy number of these which includes the hydrogenation of a-ketoesters being from industry. A large proportion of the to chiral a-hydroxyesters using chinchona alka- papers deal with reactions involving platinum loid modified platinum catalysts. group metal catalysts, reflecting their impor- A detailed study of the homogeneously pal- tance to both academia and industry. -

Phosphine Safety Data Sheet (180KB)

Phosphine Safety Data Sheet P-4643 This SDS conforms to U.S. Code of Federal Regulations 29 CFR 1910.1200, Hazard Communication. Date of issue: 01/01/1980 Revision date: 08/31/2018 Supersedes: 10/24/2016 SECTION: 1. Product and company identification 1.1. Product identifier Product form : Substance Substance name : Phosphine CAS-No. : 7803-51-2 Formula : PH3 Other means of identification : Hydrogen phosphide, Phosphorous hydride, Phosphorous trihydride, Phosphorated hydrogen 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Use of the substance/mixture : Industrial use; Use as directed. 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Praxair, Inc. 10 Riverview Drive Danbury, CT 06810-6268 - USA T 1-800-772-9247 (1-800-PRAXAIR) - F 1-716-879-2146 www.praxair.com 1.4. Emergency telephone number Emergency number : Onsite Emergency: 1-800-645-4633 CHEMTREC, 24hr/day 7days/week — Within USA: 1-800-424-9300, Outside USA: 001-703-527-3887 (collect calls accepted, Contract 17729) SECTION 2: Hazard identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture GHS-US classification Pyr. Gas H250 Flam. Gas 1 H220 Press. Gas (Liq.) H280 Acute Tox. 1 (Inhalation:gas) H330 Skin Corr. 1B H314 Eye Dam. 1 H318 Aquatic Acute 1 H400 2.2. Label elements GHS-US labeling Hazard pictograms (GHS-US) : GHS02 GHS04 GHS05 GHS06 GHS09 Signal word (GHS-US) : Danger Hazard statements (GHS-US) : H220 - EXTREMELY FLAMMABLE GAS H250 - CATCHES FIRE SPONTANEOUSLY IF EXPOSED TO AIR H280 - CONTAINS GAS UNDER PRESSURE; MAY EXPLODE IF HEATED H314 - Causes severe skin burns and eye damage H330 - FATAL IF INHALED H400 - VERY TOXIC TO AQUATIC LIFE CGA-HG04 - MAY FORM EXPLOSIVE MIXTURES WITH AIR CGA-HG11 - SYMPTOMS MAY BE DELAYED Precautionary statements (GHS-US) : P202 - Do not handle until all safety precautions have been read and understood. -

NATURE [APRIL 9, 1932 Having for Comparison a Standard Benzene Bulb

546 NATURE [APRIL 9, 1932 having for comparison a standard benzene bulb. filter transmitting 250-280 p.p. was used in these ex The powder was then melted, and recrystallised by periments. The effect was shown to have its origin heating the bulb in an electric heater to about 270° C. in the phosphine molecule, but in view of the fact and very slowly cooling it. After noting the defl.exion that phosphine itself does not absorb in the region due to the bulb with the resolidified bismuth, that of 250-280 p.p., it would seem that the incidental presence the container alone was determined by breaking it of mercury vapour resulted in the phosphine being open and dissolving out the metal with nitric acid. decomposed by excited mercury atoms into hydrogen Experiments with similar bulbs and bismuth regulus atoms and probably PH or PH2 radicals, which pro showed no change of defl.exion after heat treatment. duce the Hinshelwood-Clusius effect. Hinshelwood But when bismuth powder was melted and recrystal and Clusius concluded that the active material was lised, the diamagnetic susceptibility rose nearly to the present in the gas phase, but on repeating their ex regulus value. Many samples of colloidal bismuth periment by exposing the mixture in one tube and gave similar results. determining the explosion pressure immediately after These observations indicate that the fall in the in another similar tube, the effect was not observed. susceptibility value with reduction of particle size in That is, the effect is most probably a wall phenomenon, the case of bismuth is a genuine effect. -

US3681281.Pdf

3,681,281 United States Patent Office Patented Aug. 1, 1972 2 phosphine oxide, poly-vinyl-di-phenyl phosphine oxide, 3,681,281 tribenzyl phosphine oxide, tris-hydroxyethyl phosphine FLAME-RETARDANT POLYESTERS oxide, di-hydroxyethyl phenyl phosphine oxide, tris Charles V. Juelke, Morristown, and Louis E. Trapasso, carboxyethyl phosphine oxide, and the like. Westfield, N.J., assignors to Celanese Corporation, New The amount of additive included in the polymer depends York, N.Y. on the level of flame retardance desired in a particular No Drawing. Filed July 10, 1970, Ser. No. 54,010 application of a polyester fiber or film forming mass. Int. C. C09k 3/28; D06p3/54 About 10 weight percent or more of the additives will U.S. C. 260-45.8 N 11. Claims impart self-extinguishing properties to the polyester mass. When the additive level is lowered to below about 5 O weight percent the polyester mass is no longer self ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE extinguishing but still resists burning better than such Fibers and other shaped structures of polyesters such masses without the additive. At a level of about 1 weight as polyethylene terephthalate are rendered flame-retardant percent, while flammability is reduced, it is not sufficiently by the incorporation of tertiary phosphine oxides such 15 flame retardant for most purposes. Larger amounts than as triphenyl phosphine oxide or ethylene bis-di-phenyl those indicated serve no purpose. phosphine oxide optionally along with a synergist such In accordance with a further aspect of the invention as benzil, dibenzyl or triphenylmelamine. there may also be incorporated along with the phosphine oxide a flame retardant synergistic additive. -

Environmental Health & Safety

Environmental Health & Safety Chemical Safety Program Chemical Segregation & Incompatibilities Guidelines Class of Recommended Incompatible Possible Reaction Examples Chemical Storage Method Materials If Mixed Corrosive Acids Mineral Acids – Separate cabinet or storage area Flammable Liquids Heat Chromic Acid away from potential water Flammable Solids Hydrogen Chloride sources, i.e. under sink Bases Hydrochloric Acid Oxidizers Gas Generation Nitric Acid Poisons Perchloric Acid Violent Phosphoric Acid Reaction Sulfuric Acid Corrosive Bases/ Ammonium Hydroxide Separate cabinet or storage area Flammable Liquids Heat Caustics Sodium Hydroxide away from potential water Flammable Solids Sodium Bicarbonate sources, i.e. under sink Acids Gas Generation Oxidizers Poisons Violent Reaction Explosives Ammonium Nitrate Secure location away from Flammable Liquids Nitro Urea other chemicals Oxidizers Picric Acid Poisons Explosion Hazard Trinitroaniline Acids Trinitrobenzene Bases Trinitrobenzoic Acid Trinitrotoluene Urea Nitrate Flammable Liquids Acetone Grounded flammable storage Acids Fire Hazard Benzene cabinet of flammable storage Bases Diethyl Ether refrigerator Oxidizers Methanol Poisons Heat Ethanol Toluene Violent Glacial Acetic Acid Reaction Flammable Solids Phosphorus Separate dry cool area Acids Fire Hazard Magnesium Bases Heat Oxidizers Violent Poisons Reaction Sodium Hypochlorite Spill tray that is separate from Reducing Agents Fire Oxidizers Benzoyl Peroxide flammable and combustible Flammables Hazard Potassium Permanganate materials Combustibles -

Methyl Formate Mfm

METHYL FORMATE MFM CAUTIONARY RESPONSE INFORMATION 4. FIRE HAZARDS 7. SHIPPING INFORMATION 4.1 Flash Point: -26°F C.C. 7.1 Grades of Purity: Technical, practical, and Common Synonyms Liquid Colorless Pleasant odor 4.2 Flammable Limits in Air: 5%-22.7% spectro grades: all 97.5+% Formic acid, methyl ester 4.3 Fire Extinguishing Agents: Dry 7.2 Storage Temperature: <85°F Mixes with water. Flammable, irritating vapor is produced. Boiling point chemical, alcohol foam, carbon dioxide 7.3 Inert Atmosphere: No requirement is 88°F. 4.4 Fire Extinguishing Agents Not to Be 7.4 Venting: Pressure-vacuum Used: Water may be ineffective. 7.5 IMO Pollution Category: D Evacuate. 4.5 Special Hazards of Combustion Keep people away. Products: Not pertinent 7.6 Ship Type: 2 Shut off ignition sources. Call fire department. 4.6 Behavior in Fire: Vapor is heavier than 7.7 Barge Hull Type: Currently not available Notify local health and pollution control agencies. air and may travel considerable distance to a source of ignition and flash back. FLAMMABLE. 8. HAZARD CLASSIFICATIONS Fire 4.7 Auto Ignition Temperature: 853°F Containers may explode in fire. 8.1 49 CFR Category: Flammable liquid Flashback along vapor trail may occur. 4.8 Electrical Hazards: Currently not 8.2 49 CFR Class: 3 Vapor may explode if ignited in an enclosed area. available Extinguish with dry chemicals, alcohol foam, or carbon dioxide. 4.9 Burning Rate: 2.5 mm/min. 8.3 49 CFR Package Group: I Water may be ineffective on fire. 4.10 Adiabatic Flame Temperature: Currently 8.4 Marine Pollutant: No Cool exposed containers with water.