Poudre Fire Authority Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Fire Treatment Effectiveness for Hillslope Stabilization

United States Department of Agriculture Post-Fire Treatment Forest Service Rocky Mountain Effectiveness for Research Station General Technical Hillslope Stabilization Report RMRS-GTR-240 August 2010 Peter R. Robichaud, Louise E. Ashmun, and Bruce D. Sims A SUMMARY OF KNOWLEDGE FROM THE Robichaud, Peter R.; Ashmun, Louise E.; Sims, Bruce D. 2010. Post-fire treatment effectiveness for hill- slope stabilization. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-240. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 62 p. Abstract This synthesis of post-fire treatment effectiveness reviews the past decade of research, monitoring, and product development related to post-fire hillslope emergency stabilization treatments, including erosion barri- ers, mulching, chemical soil treatments, and combinations of these treatments. In the past ten years, erosion barrier treatments (contour-felled logs and straw wattles) have declined in use and are now rarely applied as a post-fire hillslope treatment. In contrast, dry mulch treatments (agricultural straw, wood strands, wood shreds, etc.) have quickly gained acceptance as effective, though somewhat expensive, post-fire hillslope stabilization treatments and are frequently recommended when values-at-risk warrant protection. This change has been motivated by research that shows the proportion of exposed mineral soil (or conversely, the propor- tion of ground cover) to be the primary treatment factor controlling post-fire hillslope erosion. Erosion barrier treatments provide little ground cover and have been shown to be less effective than mulch, especially during short-duration, high intensity rainfall events. In addition, innovative options for producing and applying mulch materials have adapted these materials for use on large burned areas that are inaccessible by road. -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Locatable Mineral Reports for Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming provided to the U.S. Forest Service in Fiscal Years 1996 and 1997 by Anna B. Wilson Open File Report OF 97-535 1997 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 COLORADO ...................................................................... 2 Arapaho National Forest (administered by White River National Forest) Slate Creek .................................................................. 3 Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests Winter Park Properties (Raintree) ............................................... 15 Gunnison and White River National Forests Mountain Coal Company ...................................................... 17 Pike National Forest Land Use Resource Center .................................................... 28 Pike and San Isabel National Forests Shepard and Associates ....................................................... 36 Roosevelt National Forest Larry and Vi Carpenter ....................................................... 52 Routt National Forest Smith Rancho ............................................................... 55 San Juan National -

South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September 16, 2020 MEDIA CONTACT: Bradley Whitaker, (909) 396-3456, Cell: (909) 323-9516 Nahal Mogharabi, (909) 396-3773, Cell: (909) 837-2431 [email protected] South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire Valid: Wednesday, September 16, through Thursday, September 17, 2020 This advisory is in effect through Thursday evening. South Coast AQMD will issue an update if additional information becomes available. Two major local wildfires as well as wildfires in Northern and Central California are affecting air quality in the region. A wildfire named the Bobcat Fire is burning north of Azusa and Monrovia in the Angeles National Forest. As of 6:50 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was approximately 44,393 acres with 3% containment. Current information on the Bobcat Fire can be found on the Incident Information System (InciWeb) at https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7152. A wildfire named the El Dorado Fire is burning in the San Bernardino Mountains near Yucaipa in San Bernardino County. As of 6:51 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was reported at 18,092 acres with 60% containment. Current information on the El Dorado Fire can be found on the Incident Information System at: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7148/. In addition, smoke from fires in Central California, Northern California, Oregon, and Washington are also being transported south and may impact air quality in the South Coast Air Basin and Coachella Valley. Past and Current Smoke and Ash Impacts Both the Bobcat Fire and the El Dorado fires are producing substantial amounts of smoke on Wednesday morning. -

Copyrighted Material

20_574310 bindex.qxd 1/28/05 12:00 AM Page 460 Index Arapahoe Basin, 68, 292 Auto racing A AA (American Automo- Arapaho National Forest, Colorado Springs, 175 bile Association), 54 286 Denver, 122 Accommodations, 27, 38–40 Arapaho National Fort Morgan, 237 best, 9–10 Recreation Area, 286 Pueblo, 437 Active sports and recre- Arapaho-Roosevelt National Avery House, 217 ational activities, 60–71 Forest and Pawnee Adams State College–Luther Grasslands, 220, 221, 224 E. Bean Museum, 429 Arcade Amusements, Inc., B aby Doe Tabor Museum, Adventure Golf, 111 172 318 Aerial sports (glider flying Argo Gold Mine, Mill, and Bachelor Historic Tour, 432 and soaring). See also Museum, 138 Bachelor-Syracuse Mine Ballooning A. R. Mitchell Memorial Tour, 403 Boulder, 205 Museum of Western Art, Backcountry ski tours, Colorado Springs, 173 443 Vail, 307 Durango, 374 Art Castings of Colorado, Backcountry yurt system, Airfares, 26–27, 32–33, 53 230 State Forest State Park, Air Force Academy Falcons, Art Center of Estes Park, 222–223 175 246 Backpacking. See Hiking Airlines, 31, 36, 52–53 Art on the Corner, 346 and backpacking Airport security, 32 Aspen, 321–334 Balcony House, 389 Alamosa, 3, 426–430 accommodations, Ballooning, 62, 117–118, Alamosa–Monte Vista 329–333 173, 204 National Wildlife museums, art centers, and Banana Fun Park, 346 Refuges, 430 historic sites, 327–329 Bandimere Speedway, 122 Alpine Slide music festivals, 328 Barr Lake, 66 Durango Mountain Resort, nightlife, 334 Barr Lake State Park, 374 restaurants, 333–334 118, 121 Winter Park, 286 -

COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES: COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail THE CENTENNIAL STATE The Colorado Rockies are the quintessential CDT experience! The CDT traverses 800 miles of these majestic and challenging peaks dotted with abandoned homesteads and ghost towns, and crosses the ancestral lands of the Ute, Eastern Shoshone, and Cheyenne peoples. The CDT winds through some of Colorado’s most incredible landscapes: the spectacular alpine tundra of the South San Juan, Weminuche, and La Garita Wildernesses where the CDT remains at or above 11,000 feet for nearly 70 miles; remnants of the late 1800’s ghost town of Hancock that served the Alpine Tunnel; the awe-inspiring Collegiate Peaks near Leadville, the highest incorporated city in America; geologic oddities like The Window, Knife Edge, and Devil’s Thumb; the towering 14,270 foot Grays Peak – the highest point on the CDT; Rocky Mountain National Park with its rugged snow-capped skyline; the remote Never Summer Wilderness; and the broad valleys and numerous glacial lakes and cirques of the Mount Zirkel Wilderness. You might also encounter moose, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and pika on the CDT in Colorado. In this guide, you’ll find Colorado’s best day and overnight hikes on the CDT, organized south to north. ELEVATION: The average elevation of the CDT in Colorado is 10,978 ft, and all of the hikes listed in this guide begin at elevations above 8,000 ft. Remember to bring plenty of water, sun protection, and extra food, and know that a hike at elevation will likely be more challenging than the same distance hike at sea level. -

Laramie River District, Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, R-2

Laramie River District, Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, R-2. [1962?] Scale, ca. 1:63,360. No geographic coordinates. Public Land (Township & Range) grid. Black & white. 94 x 76 cm. Relief shown by hachures. Shows the Laramie River Ranger District of the Roosevelt National Forest along with national forest boundaries, roads, railroads, Forest Service administrative facilities, rivers, lakes, and streams. “Sixth Principal Meridian.” Holdings: Colorado State Univ. OCLC: 228071611 Poudre District, Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, R-2. [1962?] Scale, ca. 1:63,360. No geographic coordinates. Public Land (Township & Range) grid. Black & white. 76 x 128 cm. Relief shown by hachures. Shows the Poudre Ranger District of the Roosevelt National Forest along with national forest boundaries, roads, railroads, Forest Service administrative facilities, rivers, lakes, and streams. “Sixth Principal Meridian.” Holdings: Colorado State Univ. OCLC: 228073225 Redfeather District, Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, R-2. [1962?] Scale, ca. 1:63,360. No geographic coordinates. Public Land (Township & Range) grid. Black & white. 77 x 122 cm. Relief shown by hachures. Shows the Red Feather Ranger District of the Roosevelt National Forest along with national forest boundaries, roads, railroads, Forest Service administrative facilities, rivers, lakes, and streams. “Sixth Principal Meridian.” Holdings: Colorado State Univ. OCLC: 228073030 Boulder District, Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, R-2. 1968. Scale, ca. 1:63,360. No geographic coordinates. Public Land (Township & Range) grid. Black & white. 80 x 71 cm. Relief shown by hachures. -

Cal Fire: Creek Fire Now the Largest Single Wildfire in California History

Cal Fire: Creek Fire now the largest single wildfire in California history By Joe Jacquez Visalia Times-Delta, Wednesday, September 23, 2020 The Creek Fire is now the largest single, non-complex wildfire in California history, according to an update from Cal Fire. The fire has burned 286,519 acres as of Monday night and is 32 percent contained, according to Cal Fire. The Creek Fire, which began Sept. 4, is located in Big Creek, Huntington Lake, Shaver Lake, Mammoth Pool and San Joaquin River Canyon. Creek Fire damage realized There were approximately 82 Madera County structures destroyed in the blaze. Six of those structures were homes, according to Commander Bill Ward. There are still more damage assessments to be made as evacuation orders are lifted and converted to warnings. Madera County sheriff's deputies notified the residents whose homes were lost in the fire. The Fresno County side of the fire sustained significantly more damage, according to Truax. "We are working with (Fresno County) to come up with away to get that information out," Incident Commander Nick Truax said. California wildfires:Firefighters battle more than 25 major blazes, Bobcat Fire grows Of the 4,900 structures under assessment, 30% have been validated using Fresno and Madera counties assessor records. Related: 'It's just too dangerous': Firefighters make slow progress assessing Creek Fire damage So far, damage inspection teams have counted more than 300 destroyed structures and 32 damaged structures. "These are the areas we can safely get to," Truax said. "There are a lot of areas that trees have fallen across the roads. -

2021 OHV Grant Recommended Funding Approval

State Trails Program 13787 US Hwy. 85 N., Littleton, Colorado 80125 P 303.791.1957 | F 303.470-0782 May 6-7, 2020 2020-2021 OHV Trail Grant funding awards as recommended by the State Recreational Trails Committee. This letter is a summary and explanation of the enclosed Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) 2020-2021 OHV Trail Grant funding recommendations for Parks and Wildlife Commission (PWC) approval during the May 2020 meeting. We are requesting approval for 60 grants for a total award amount of $4,273,860. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The Colorado Parks and Wildlife Division’s (CPW) Trails Program, a statewide program within CPW, administers grants for trail-related projects on an annual basis. Local, county, and state governments, federal agencies, special recreation districts, and non-profit organizations with management responsibilities over public lands may apply for and are eligible to receive non- motorized and motorized trail grants. Colorado’s Off-highway Vehicle Trail Program CPW’s OHV Program is statutorily created in sections 33-14.5-101 through 33-14.5-113, Colorado Revised Statutes. The program is funded through the sale of OHV registrations and use permits. It is estimated that almost 200,000 OHVs were registered or permitted for use in Colorado during the 2019-2020 season. The price of an annual OHV registration or use- permit is $25.25. Funds are used to support the statewide OHV Program, the OHV Registration Program and OHV Trail Grant Program, including OHV law enforcement. The OHV Program seeks to improve and enhance motorized recreation opportunities in Colorado while promoting safe, responsible use of OHVs. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Brea Fire Department 2020 Annual Report Brea Fire Annual Report 2020 a Message from Your Brea Fire Chief

7 91 S . 1 M EST E UE FIRE RESC BREA2020 FIRE ANNUAL DEPARTMENT REPORT BREA FIRE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 A MESSAGE FROM YOUR BREA FIRE CHIEF I’m extremely proud to introduce our first ever Brea Fire Department Annual Report for 2020! This was a year filled with many unique challenges from a worldwide pandemic, to extreme wildfires, to civil unrest. Throughout these challenges, the men and women of the Brea Fire Department continued to respond to our community as compassionate professionals. As a highly trained, all-hazard fire department, we take great pride in handling any situation that comes our way. It is important to take time to reflect on our past accomplishments so we remain focused to exceed the following year’s expectations. More importantly, this is our opportunity to provide a behind-the-scenes look at the details of your fire department and the positive impact they are having on our community. It is our belief that the quality of life in our neighborhoods depends on strong partnerships between our citizens, business leaders, elected officials, and City employees. We welcome every opportunity to participate in these partnerships, especially as we continue to move back to our normal way of life. ADAM LOESER BREA FIRE CHIEF BREA FIRE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 PROTECTING OUR CITY Each member of our team has a heart for serving the City of Brea. From our Firefighters to our volunteers, Brea is in great hands. 42 RON ARISTONDO FIREFIGHTERS Fire Prevention Specialist II 3 YEARS OF BREA SERVICE 3 FIRE PREVENTION STAFF 1 JOHN AGUIRRE EMERGENCY Fire Engineer MANAGER 25 YEARS OF BREA SERVICE 2 PROFESSIONAL STAFF ELIZABETH DANG Administrative Clerk II 164 7 YEARS OF BREA SERVICE COMMUNITY EMERGENCY RESPONSE TEAM (CERT) VOLUNTEERS 8 CHIEF OFFICERS* 1 EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES (EMS) MANAGER* 1 FIRE CHAPLAIN* *Shared with the City of Fullerton BREA FIRE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 COMMAND STAFF Since 2011, the cities of Brea and Fullerton have operated under a Shared Command Staff Agreement. -

Medicine Bow-Routt National Forests

Report of the Rocky Mountain Region (R2) 2015 Forest Health Conditions Section 1 - 2015 Forest Health (FH) conditions of the National Forests (NF) in the Rocky Mountain Region (R2). These 12 reports were produced by the 3 Forest Health Protection (FHP) Service Centers in R2 and assist the national forest managers with their forest health concerns. Section 1 contains the original reports with figures, maps, and photos labeled as in the original reports written by R2 FHP – Gunnison, Lakewood, and Rapid City Service Centers. Section 2 – Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming 2015 Forest Health Highlights (FHH) reports internet links to the FH Monitoring website. The FHH reports were produced by state forest health specialists to the latest FHH from all forestlands in each state. Section 3 - The 2015 Aerial Detection Survey (ADS) summary report for the Rocky Mountain Region (R2) produced by the surveyors and specialists of the ADS program. Here is the original, Nov. 2015, report along with its graphics and tables. Section 4 - Additional documentation and acknowledgements comprise Section 4. Required documentation for all US Government reports and a listing of all contributors for this report are presented. Go to the Table of Contents for 2015 Rocky Mountain Region Forest Health Conditions report Approved by SPFH Director – July 2016 Caring for the Land and Serving People 2 Table of Contents for 2015 Rocky Mountain Region Pages – Forest Health Conditions Section 1: 2015 Forest Health Conditions of the National Forests in 1 - -

Board Agenda and Report Packet

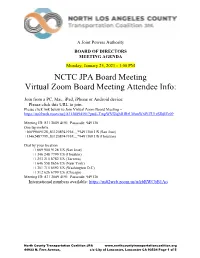

A Joint Powers Authority BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING AGENDA Monday, January 25, 2021 - 1:00 PM NCTC JPA Board Meeting Virtual Zoom Board Meeting Attendee Info: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone or Android device: Please click this URL to join. Please click link below to Join Virtual Zoom Board Meeting – https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83120894191?pwd=TmpWVGlqMHRzU0hmWnlYZU1zSDdlZz09 Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 One tap mobile +16699009128,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (San Jose) +13462487799,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (Houston) Dial by your location +1 669 900 9128 US (San Jose) +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 646 558 8656 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington D.C) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 International numbers available: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbRWCbB1Ao North County Transportation Coalition JPA www.northcountytransportationcoalition.org 44933 N. Fern Avenue, c/o City of Lancaster, Lancaster CA 93534 Page 1 of 5 NCTC JPA BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBERS Chair, Supervisor Kathryn Barger, 5th Supervisorial District, County of Los Angeles Mark Pestrella, Director of Public Works, County of Los Angeles Victor Lindenheim, County of Los Angeles Austin Bishop, Council Member, City of Palmdale Laura Bettencourt, Council Member, City of Palmdale Bart Avery, City of Palmdale Marvin Crist, Vice Mayor, City of Lancaster Kenneth Mann, Council Member, City of Lancaster Jason Caudle, City Manager, City of Lancaster Marsha McLean, Council Member, City of Santa Clarita Robert Newman, Director of Public Works, City of Santa Clarita Vacant, City of Santa Clarita EX-OFFICIO BOARD MEMBERS Macy Neshati, Antelope Valley Transit Authority Adrian Aguilar, Santa Clarita Transit BOARD MEMBER ALTERNATES Dave Perry, County of Los Angeles Juan Carrillo, Council Member, City of Palmdale Mike Hennawy, City of Santa Clarita NCTC JPA STAFF Executive Director: Arthur V.