Species Status Assessment Report for the Macgillivray's Seaside Sparrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene and Transposable Element Expression

Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae) Delphine Giraud, Oscar Lima, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin, Armel Salmon, Malika Ainouche To cite this version: Delphine Giraud, Oscar Lima, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin, Armel Salmon, Malika Ainouche. Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae). Frontiers in Genetics, 2021, 12, 10.3389/fgene.2021.589160. hal-03216905 HAL Id: hal-03216905 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03216905 Submitted on 4 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License fgene-12-589160 March 19, 2021 Time: 12:36 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 25 March 2021 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.589160 Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae) Delphine Giraud1, Oscar Lima1, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin2, Armel Salmon1 and Malika Aïnouche1* 1 UMR CNRS 6553 Ecosystèmes, Biodiversité, Evolution (ECOBIO), Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France, 2 IGEPP, INRAE, Institut Agro, Univ Rennes, Le Rheu, France Gene expression dynamics is a key component of polyploid evolution, varying in nature, intensity, and temporal scales, most particularly in allopolyploids, where two or more sub-genomes from differentiated parental species and different repeat contents are merged. -

Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow Ammodramus Maritimus Mirabilis

Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis ape Sable seaside sparrows (Ammodramus Federal Status: Endangered (March 11, 1967) maritimus mirabilis) are medium-sized sparrows Critical Habitat: Designated (August 11, 1977) Crestricted to the Florida peninsula. They are non- Florida Status: Endangered migratory residents of freshwater to brackish marshes. The Cape Sable seaside sparrow has the distinction of being the Recovery Plan Status: Revision (May 18, 1999) last new bird species described in the continental United Geographic Coverage: Rangewide States prior to its reclassification to subspecies status. The restricted range of the Cape Sable seaside sparrow led to its initial listing in 1969. Changes in habitat that have Figure 1. County distribution of the Cape Sable seaside sparrrow. occurred as a result of changes in the distribution, timing, and quantity of water flows in South Florida, continue to threaten the subspecies with extinction. This account represents a revision of the existing recovery plan for the Cape Sable seaside sparrow (FWS 1983). Description The Cape Sable seaside sparrow is a medium-sized sparrow, 13 to 14 cm in length (Werner 1975). Of all the seaside sparrows, it is the lightest in color (Curnutt 1996). The dorsal surface is dark olive-grey and the tail and wings are olive- brown (Werner 1975). Adult birds are light grey to white ventrally, with dark olive grey streaks on the breast and sides. The throat is white with a dark olive-grey or black whisker on each side. Above the whisker is a white line along the lower jaw. A grey ear patch outlined by a dark line sits behind each eye. -

Emergency Management Action Plan for the Endangered Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow Ammodramus Maritimus Mirabilis

Emergency Management Action Plan for the endangered Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis Federal Status Endangered (March 11, 1967) Florida Status Endangered Range Endemic to Florida Everglades Population Estimate ~ 2,000 to 3,500 birds Current Population Trend Stable Habitat Marl prairie Major Threats Habitat loss and degradation, altered hydrology and fire regimes Recovery Plan Objective Down listing from ‘Endangered’ to ‘Threatened’ Develop a decision framework to help rapidly guide sparrow EMAP Goal emergency management actions Identify the situations or events that would trigger an emergency EMAP Objective management action and provide the details for each action. Gary L. Slater1,2 Rebecca L. Boulton1,3 Clinton N. Jenkins4 Julie L. Lockwood3 Stuart L. Pimm4 A report to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service South Florida Ecological Services Office Vero Beach, FL 32960 1 Authors contributed equally to report 2 Ecostudies Institute, Mount Vernon, WA 98273; Corresponding author ([email protected]) 3 Department of Ecology, Evolution, & Natural Resources, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 4 Environmental Sciences & Policy, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 Ecostudies Institute committed to ecological research and conservation AUTHORS GARY SLATER; is the founder and research director of Ecostudies Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to conducting sound science and conservation. Gary's qualifications and experience span two important areas in conservation science: administrative/program management and independent research. Since 1993, he has conducted research on the avifauna of the south Florida pine rocklands, including the last 10 years planning, implementing, and monitoring the reintroduction of the Brown-headed Nuthatch (Sitta pusilla) and Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis) to Everglades National Park. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

Sporobolus Latzii B.K.Simon (POACEAE)

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory Sporobolus latzii B.K.Simon (POACEAE) Conservation status Australia: Not listed Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: D. Albrecht Description less than 200 plants were found there. Given, however, that the region is relatively poorly Sporobolus latzii is a fairly robust erect tufted sampled (with less than two flora survey or perennial grass with flowering stems to collection points per 100 km2) the existence almost 1 m high from a short rhizome. The of additional populations cannot presently be leaves are minutely roughened, flat and to 16 ruled out. The swamps surveyed represent cm long and 3.5 mm wide. Spikelets are 2-2.3 approximately one third to one half of the mm long and arranged in a panicle 11-13 cm potential swamps in the region (P. Latz pers. long. The main branches of the inflorescence comm.). are solitary and spikelet-bearing throughout. Conservation reserves where reported: None Flowering: recorded in May. Distribution Sporobolus latzii is endemic to the Northern Territory (NT) where it is known only from the type locality in the Wakaya Desert (east of the Davenport Ranges and south of the Barkly Tablelands). The species was originally discovered in 1993 during a biological survey of the Wakaya Desert (Gibson et al. 1994). Some 40 swamps in the Wakaya Desert and additional similar Known locations of Sporobolus latzii swamps to the north of the Wakaya Desert were visited in the course of this survey work, Ecology but Sporobolus latzii was only found at the one Sporobolus latzii occurs in clay soil on the edge site (the type locality; P.Latz pers. -

Endangered Species

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Endangered species From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents For other uses, see Endangered species (disambiguation). Featured content "Endangered" redirects here. For other uses, see Endangered (disambiguation). Current events An endangered species is a species which has been categorized as likely to become Random article Conservation status extinct . Endangered (EN), as categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Donate to Wikipedia by IUCN Red List category Wikipedia store Nature (IUCN) Red List, is the second most severe conservation status for wild populations in the IUCN's schema after Critically Endangered (CR). Interaction In 2012, the IUCN Red List featured 3079 animal and 2655 plant species as endangered (EN) Help worldwide.[1] The figures for 1998 were, respectively, 1102 and 1197. About Wikipedia Community portal Many nations have laws that protect conservation-reliant species: for example, forbidding Recent changes hunting , restricting land development or creating preserves. Population numbers, trends and Contact page species' conservation status can be found in the lists of organisms by population. Tools Extinct Contents [hide] What links here Extinct (EX) (list) 1 Conservation status Related changes Extinct in the Wild (EW) (list) 2 IUCN Red List Upload file [7] Threatened Special pages 2.1 Criteria for 'Endangered (EN)' Critically Endangered (CR) (list) Permanent link 3 Endangered species in the United -

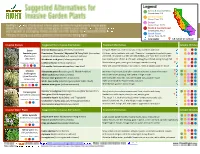

Suggested Non-Invasive Alternatives Invasive Grasses Suggested Non

Sierra & Coastal Mtns. (Sunset Zones 1-3) Central Valley (Sunset Zones 7-9) Desert (Sunset Zones 10-13) North & Central Coast (Sunset Zones 14-17) South Coast (Sunset Zones 18-24) Low water CA native or cultivar Invasive Grasses Suggested Non-invasive Alternatives Featured Information Suitable Climates Green Oriental fountain grass (Pennisetum orientale) Compact, floriferous, cold hardy, very similar aesthetic and habit fountain grass Pennisetum ‘Fireworks’,‘Skyrocket’ & ‘Fairy Tails’ (Pennisetum Cultivars, similar aesthetic and habit. ‘Fireworks’ is magenta striped with green (Pennisetum x advena, often mislabeled as P. setaceum cultivars) and white. ‘Skyrocket’ is green with white edges, and ‘Fairy Tails’ is solid green setaceum) Mendocino reed grass (Calamagrostis foliosa) Cool-season grass 1 ft. tall & 2 ft. wide. Arching flower heads spring through fall Invasive in climate zones: California fescue (Festuca californica) Shade tolerant grass, needs good drainage, tolerates mowing Pink muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris 'Regal Mist’) Fluffy pink cloud-like blooms, frost tolerant, needs drainage, good en masse Mexican Blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis 'Blonde Ambition') Attractive flowerheads, best when cut back in winter, cultivar of CA native feathergrass Alkali sacaton (Sporobolus airoides) Robust yet slower growing, does well in a range of soils (Stipa/Nassella Mexican deer grass (Muhlenbergia dubia) Semi-evergreen mounder, likes well-drained soils, good en masse tenuissima) White awn muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris 'White Cloud') Fluffy white cloud-like flower heads, easy care Invasive in climate zones: Autumn moor grass (Sesleria autumnalis) Neat clumper, good en masse, tough Pampas grass Foerster's reed grass (Calamagrostis x acutiflora 'Karl Foerster') Stately white plumes from summer until frost, durable and showy (Cortaderia selloana) Deer grass (Muhlenbergia rigens) Smaller form with simple, clean plumes, easy to grow Lomandra hystrix 'Katie Belles' and 'Tropicbelle' Tidy, tough, 4 ft. -

Scott's Seaside Sparrow Biological Status Review Report

Scott’s Seaside Sparrow Biological Status Review Report March 31, 2011 FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION 620 South Meridian Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1600 Biological Status Review Report for the Scott’s Seaside Sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus peninsulae) March 31, 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) directed staff to evaluate all species listed as Threatened or Species of Special Concern as of November 8, 2010 that had not undergone a status review in the past decade. Public information on the status of the Scott’s seaside sparrow was sought from September 17 to November 1, 2010. The three-member Biological Review Group (BRG) met on November 3 - 4, 2010. Group members were Michael F. Delany (FWC lead), Katy NeSmith (Florida Natural Areas Inventory), and Bill Pranty (Avian Ecologist Contractor) (Appendix 1). In accordance with rule 68A-27.0012, Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.), the BRG was charged with evaluating the biological status of the Scott’s seaside sparrow using criteria included in definitions in 68A-27.001, F.A.C., and following the protocols in the Guidelines for Application of the IUCN Red List Criteria at Regional Levels (Version 3.0) and Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (Version 8.1). Please visit http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/imperiled/listing-action- petitions/ to view the listing process rule and the criteria found in the definitions. In late 2010, staff developed the initial draft of this report which included BRG findings and a preliminary listing recommendation from staff. The draft was sent out for peer review and the reviewers’ input has been incorporated to create this final report. -

Ecological and Genetic Diversity in the Seaside Sparrow

BIOLOGY OF THE EMBERIZIDAE Ecological and Genetic Diversity in the Seaside Sparrow he Seaside Sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus), a sparrow that is almost T always found in salt and brackish marshes, occurs along the Atlantic Coast of the United States from New Hampshire to central Florida (where it is now extirpated as a breeder), and along the Gulf Coast from central Florida to central Texas. As a species that can be common in maritime wetlands, the Seaside Sparrow has the potential to be a good “indicator species” of the health of salt- marshes: Where the marshes are in good condition, the birds are abundant; where the marshes are degraded, they are less common or absent. Degradation of habi- tat—walling, diking, draining, and pollution—are the principal threats to this species, having resulted in the extirpation of multiple populations, including sev- eral named taxa. Along the Atlantic coast, where the species has been closely studied (Woolfenden 1956; Norris 1968; Post 1970, 1981; Post et James D. Rising al. 1983; DeRagon 1988 in Post and Greenlaw 1994), densities, measured Department of Zoology as males per hectare, range from 0.6–1.0 in degraded habitats to 0.3–20.0 in undrained and unaltered marshes. University of Toronto First described and named by Alexander Wilson, the “Father of Ameri- Toronto ON M53 3G5 can Ornithology”, in 1811, on the basis of specimens from southern New Jersey (Great Egg Harbor), the Seaside Sparrow is a polytypic species (i.e., [email protected] a species showing geographic variation, with more than one named sub- species) with a complex taxonomic history (Austin 1983). -

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus Adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2020 Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes Emily Rebecca Mausteller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Mausteller, Emily Rebecca, "Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes" (2020). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1313. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1313 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS ADAMANTEUS) AMBUSH SITE SELECTION IN COASTAL SALTWATER MARSHES A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biological Sciences by Emily Rebecca Mausteller Approved by Dr. Shane Welch, Committee Chairperson Dr. Jayme Waldron Dr. Anne Axel Marshall University December 2020 i APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Emily Mausteller, affirm that the thesis, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the Biological Sciences Program and the College of Science. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. -

Alien Flora of Europe: Species Diversity, Temporal Trends, Geographical Patterns and Research Needs

Preslia 80: 101–149, 2008 101 Alien flora of Europe: species diversity, temporal trends, geographical patterns and research needs Zavlečená flóra Evropy: druhová diverzita, časové trendy, zákonitosti geografického rozšíření a oblasti budoucího výzkumu Philip W. L a m b d o n1,2#, Petr P y š e k3,4*, Corina B a s n o u5, Martin H e j d a3,4, Margari- taArianoutsou6, Franz E s s l7, Vojtěch J a r o š í k4,3, Jan P e r g l3, Marten W i n t e r8, Paulina A n a s t a s i u9, Pavlos A n d r i opoulos6, Ioannis B a z o s6, Giuseppe Brundu10, Laura C e l e s t i - G r a p o w11, Philippe C h a s s o t12, Pinelopi D e l i p e t - rou13, Melanie J o s e f s s o n14, Salit K a r k15, Stefan K l o t z8, Yannis K o k k o r i s6, Ingolf K ü h n8, Hélia M a r c h a n t e16, Irena P e r g l o v á3, Joan P i n o5, Montserrat Vilà17, Andreas Z i k o s6, David R o y1 & Philip E. H u l m e18 1Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Hill of Brathens, Banchory, Aberdeenshire AB31 4BW, Scotland, e-mail; [email protected], [email protected]; 2Kew Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AB, United Kingdom; 3Institute of Bot- any, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; 4Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 7, CZ-128 01 Praha 2, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected]; 5Center for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]; 6University of Athens, Faculty of Biology, Department of Ecology & Systematics, 15784 Athens, Greece, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; 7Federal Environment Agency, Department of Nature Conservation, Spittelauer Lände 5, 1090 Vienna, Austria, e-mail: [email protected]; 8Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ, Department of Community Ecology, Theodor-Lieser- Str.