Notes on the Economics of Household Energy Consumption and Technology Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, Volume 4, number 1 Volume Author/Editor: Sanford V. Berg, editor Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/aesm75-1 Publication Date: 1975 Chapter Title: The Theory of Household Behavior: Some Foundations Chapter Author: Kelvin Lancaster Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10216 Chapter pages in book: (p. 5 - 21) Annals a! E won;ic and Ss to!fea.t ure,twn t, 4 1975 THE THEORY OF IIOUSEIIOLI) BEHAVIOR: SOME FOUNDATIONS wt' K1LVIN LANCASTER* This paper is concerned with examining the common practice of considering the household to act us if it were a single individuaL Iconcludes rhut aggregate household behavior wifl diverge front the behavior of the typical individual in Iwo important respects, but that the degree of this divergence depend: on well-defined variables--the number of goods and characteristics in the consu;npf ion fecIJflolOgv relative to the size of the household, and thextent of joint consumption within the houseiwid. For appropriate values of these, the degree of divergence may be very small or zero. For some years now, it has been common to refer to the basic decision-making entity with respect to consumption as the "household" by those primarily con- cerned with data collection and analysis and those working mainly with macro- economic models, and as the "individua1' by those working in microeconomic theory and welfare economics. Although one-person households do exist, they are the exception rather than the rule, and the individual and the household cannot be taken to be identical. -

Journal of Econometrics Consumption and Labor Supply

Journal of Econometrics 147 (2008) 326–335 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Econometrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jeconom Consumption and labor supply Dale W. Jorgenson a,∗, Daniel T. Slesnick b a Department of Economics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States b Department of Economics, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We present a new econometric model of aggregate demand and labor supply for the United States. Available online 16 September 2008 We also analyze the allocation full wealth among time periods for households distinguished by a variety of demographic characteristics. The model is estimated using micro-level data from the Consumer JEL classification: Expenditure Surveys supplemented with price information obtained from the Consumer Price Index. An C81 important feature of our approach is that aggregate demands and labor supply can be represented in D12 D91 closed form while accounting for the substantial heterogeneity in behavior that is found in household- level data. As a result, we are able to explain the patterns of aggregate demand and labor supply in the Keywords: data despite using a parametrically parsimonious specification. Consumption ' 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Leisure Labor Demand Supply Wages 1. Introduction employed, we impute the opportunity wages they face using the wages earned by employees. The objective of this paper is to present a new econometric Cross-sectional variation of prices and wages is considerable model of aggregate consumer behavior for the United States. The and provides an important source of information about patterns model allocates full wealth among time periods for households of consumption and labor supply. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from on the Subjection of Women John

1 John Stuart Mill Selections from On the Subjection of Women John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was an English philosopher, economist, and essayist. He was raised in strict accord with utilitarian principles by his economist father James Mill, the founder of utilitarian philosophy. John Stuart recorded his early training and subsequent near breakdown in in his Autobiography (“A Crisis in My Mental History. One Stage Onward”), published after his death by his step-daughter, Helen Taylor, in 1873. His strictly intellectual training led to an early crisis which, as he records in this chapter, was only relieved by reading the poetry of William Wordsworth. During his life, Mill published a number of works on economic and political issues, including the Principles of Political Economy (1848), Utilitarianism (1863), and On Liberty (1859). After his death, besides the Autobiography, his step-daughter published Three Essays on Religion in 1874. On the Subjection of Women (1869) is Mill’s utilitarian argument for the complete equality of women with men. Scholars think that it was greatly influenced by Mill’s discussions with Harriet Taylor, whom Mill married in 1851. The essay is addressed to men, the rulers and controllers of nineteenth-century society, and is his contribution to what had become known as “the woman question,” that is, what liberties should be accorded to women in society. As such, it is a clear and still-relevant contribution to the ongoing discussion of women’s rights and their desire to achieve what Mill announces in his opening thesis, “perfect equality.” Information readily available on the internet has not been glossed. -

Product Differentiation

Product differentiation Industrial Organization Bernard Caillaud Master APE - Paris School of Economics September 22, 2016 Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation The Bertrand paradox relies on the fact buyers choose the cheap- est firm, even for very small price differences. In practice, some buyers may continue to buy from the most expensive firms because they have an intrinsic preference for the product sold by that firm: Notion of differentiation. Indeed, assuming an homogeneous product is not realistic: rarely exist two identical goods in this sense For objective reasons: products differ in their physical char- acteristics, in their design, ... For subjective reasons: even when physical differences are hard to see for consumers, branding may well make two prod- ucts appear differently in the consumers' eyes Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation Differentiation among products is above all a property of con- sumers' preferences: Taste for diversity Heterogeneity of consumers' taste But it has major consequences in terms of imperfectly competi- tive behavior: so, the analysis of differentiation allows for a richer discussion and comparison of price competition models vs quan- tity competition models. Also related to the practical question (for competition authori- ties) of market definition: set of goods highly substitutable among themselves and poorly substitutable with goods outside this set Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation Firms have in general an incentive to affect the degree of differ- entiation of their products compared to rivals'. Hence, differen- tiation is related to other aspects of firms’ strategies. Choice of products: firms choose how to differentiate from rivals, this impacts the type of products that they choose to offer and the diversity of products that consumers face. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

What Role Does Consumer Sentiment Play in the U.S. Economy?

The economy is mired in recession. Consumer spending is weak, investment in plant and equipment is lethargic, and firms are hesitant to hire unemployed workers, given bleak forecasts of demand for final products. Monetary policy has lowered short-term interest rates and long rates have followed suit, but consumers and businesses resist borrowing. The condi- tions seem ripe for a recovery, but still the economy has not taken off as expected. What is the missing ingredient? Consumer confidence. Once the mood of consumers shifts toward the optimistic, shoppers will buy, firms will hire, and the engine of growth will rev up again. All eyes are on the widely publicized measures of consumer confidence (or consumer sentiment), waiting for the telltale uptick that will propel us into the longed-for expansion. Just as we appear to be headed for a "double-dipper," the mood swing occurs: the indexes of consumer confi- dence register 20-point increases, and the nation surges into a prolonged period of healthy growth. oes the U.S. economy really behave as this fictional account describes? Can a shift in sentiment drive the economy out of D recession and back into good health? Does a lack of consumer confidence drag the economy into recession? What causes large swings in consumer confidence? This article will try to answer these questions and to determine consumer confidence’s role in the workings of the U.S. economy. ]effre9 C. Fuhrer I. What Is Consumer Sentitnent? Senior Econotnist, Federal Reserve Consumer sentiment, or consumer confidence, is both an economic Bank of Boston. -

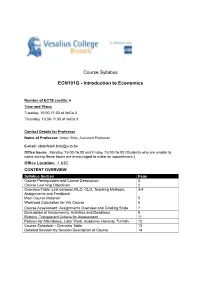

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

Demand Composition and the Strength of Recoveries†

Demand Composition and the Strength of Recoveriesy Martin Beraja Christian K. Wolf MIT & NBER MIT & NBER September 17, 2021 Abstract: We argue that recoveries from demand-driven recessions with ex- penditure cuts concentrated in services or non-durables will tend to be weaker than recoveries from recessions more biased towards durables. Intuitively, the smaller the bias towards more durable goods, the less the recovery is buffeted by pent-up demand. We show that, in a standard multi-sector business-cycle model, this prediction holds if and only if, following an aggregate demand shock to all categories of spending (e.g., a monetary shock), expenditure on more durable goods reverts back faster. This testable condition receives ample support in U.S. data. We then use (i) a semi-structural shift-share and (ii) a structural model to quantify this effect of varying demand composition on recovery dynamics, and find it to be large. We also discuss implications for optimal stabilization policy. Keywords: durables, services, demand recessions, pent-up demand, shift-share design, recov- ery dynamics, COVID-19. JEL codes: E32, E52 yEmail: [email protected] and [email protected]. We received helpful comments from George-Marios Angeletos, Gadi Barlevy, Florin Bilbiie, Ricardo Caballero, Lawrence Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum, Fran¸coisGourio, Basile Grassi, Erik Hurst, Greg Kaplan, Andrea Lanteri, Jennifer La'O, Alisdair McKay, Simon Mongey, Ernesto Pasten, Matt Rognlie, Alp Simsek, Ludwig Straub, Silvana Tenreyro, Nicholas Tra- chter, Gianluca Violante, Iv´anWerning, Johannes Wieland (our discussant), Tom Winberry, Nathan Zorzi and seminar participants at various venues, and we thank Isabel Di Tella for outstanding research assistance. -

I. Externalities

Economics 1410 Fall 2017 Harvard University SECTION 8 I. Externalities 1. Consider a factory that emits pollution. The inverse demand for the good is Pd = 24 − Q and the inverse supply curve is Ps = 4 + Q. The marginal cost of the pollution is given by MC = 0:5Q. (a) What are the equilibrium price and quantity when there is no government intervention? (b) How much should the factory produce at the social optimum? (c) How large is the deadweight loss from the externality? (d) How large of a per-unit tax should the government impose to achieve the social optimum? 2. In Karro, Kansas, population 1,001, the only source of entertainment available is driving around in your car. The 1,001 Karraokers are all identical. They all like to drive, but hate congestion and pollution, resulting in the following utility function: Ui(f; d; t) = f + 16d − d2 − 6t=1000, where f is consumption of all goods but driving, d is the number of hours of driving Karraoker i does per day, and t is the total number of hours of driving all other Karraokers do per day. Assume that driving is free, that the unit price of food is $1, and that daily income is $40. (a) If an individual believes that the amount of driving he does wont affect the amount that others drive, how many hours per day will he choose to drive? (b) If everybody chooses this number of hours, then what is the total amount t of driving by other persons? (c) What will the utility of each resident be? (d) If everybody drives 6 hours a day, what will the utility level of each Karraoker be? (e) Suppose that the residents decided to pass a law restricting the total number of hours that anyone is allowed to drive. -

Utility with Decreasing Risk Aversion

144 UTILITY WITH DECREASING RISK AVERSION GARY G. VENTER Abstract Utility theory is discussed as a basis for premium calculation. Desirable features of utility functions are enumerated, including decreasing absolute risk aversion. Examples are given of functions meeting this requirement. Calculating premiums for simplified risk situations is advanced as a step towards selecting a specific utility function. An example of a more typical portfolio pricing problem is included. “The large rattling dice exhilarate me as torrents borne on a precipice flowing in a desert. To the winning player they are tipped with honey, slaying hirri in return by taking away the gambler’s all. Giving serious attention to my advice, play not with dice: pursue agriculture: delight in wealth so acquired.” KAVASHA Rig Veda X.3:5 Avoidance of risk situations has been regarded as prudent throughout history, but individuals with a preference for risk are also known. For many decision makers, the value of different potential levels of wealth is apparently not strictly proportional to the wealth level itself. A mathematical device to treat this is the utility function, which assigns a value to each wealth level. Thus, a 50-50 chance at double or nothing on your wealth level may or may not be felt equivalent to maintaining your present level; however, a 50-50 chance at nothing or the value of wealth that would double your utility (if such a value existed) would be equivalent to maintaining the present level, assuming that the utility of zero wealth is zero. This is more or less by definition, as the utility function is set up to make such comparisons possible.