The Caheri Gutierrez Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

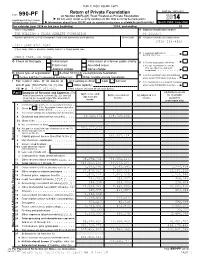

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

Mathmatters and STEAM Expo

Winter 2016-2017 NEWSLETTER MathMatters and STEAM Expo On Saturday, March 18th, Coral Academy of Science Las Vegas will host the 13th annual math contest, MathMatters and our annual STEAM Expo. Executive Director Letter This marks the first year both events will happen concurrently. Central Office Note Our long-established K-12 STEAM Expo is going to be held at Sandy Ridge Sandy Ridge Principal’s Park, Henderson. Students from all five branches of Coral Academy of Note Science, Las Vegas will come together to make this amazing event more Upcoming Events fascinating. Additionally this year there will be art booths as well. This 2017-2018 Calendar free event will help raise funds for many clubs and groups as well as ex- pose our community to all that our students have to offer. Nellis AFB Principal’s Note MathMatters will be held at the Sandy Ridge Campus. The event is free Centennial Hills and open to all 4th and 5th grade students throughout the Las Vegas Val- Principal’s Note ley but pre-registration is required. Students will test their skills by solv- ing 15 challenging math questions ranging from fractions to operations Windmill Principal’s and algebraic thinking. All attendees will enjoy the science demonstra- Note tion on defying gravity by Mad Science of Las Vegas. Tamarus Principal’s Note Winners of the competition will win prizes including: 1st place prize: IPAD Mini2 Accolades 2nd place prize: Kindle Fire HD 8 Student Highlights 3rd place prize: Kindle Fire MathMatters registration information will be coming soon. Reminders We are now accepting online applications for the 2017-2018 school year. -

Lisa DEL SOL Columbia University

7 Race Relations and Conversations as Hip-Hop Calls Out Anime In TweRk by Latasha N. Nevada Diggs Lisa DEL SOL Columbia University The poetry of Latasha N. Nevada Diggs (2013) moves beyond the conventional boundaries separating music and text within traditional Western literature in her book TweRk. By both actively connecting and fusing music and text into this body of work she creates a text with a sonic element that moves beyond the boundaries of the page. Diggs (2013) further complicates the relationship between text, sound and visual media in her poetry which is a fusion of pop culture, rhythm, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and a multitude of languages (including various Caribbean Patois) making it difficult to categorize her poetry due to its polyphonic nature. Diggs’s (2013) poetry ranges from references and direct quotes from hip-hop songs (such as titles and lyrics), as well as alluding to particular rhythms all while addressing stereotypes of sexism and combatting worldwide images of anti-blackness. I will discuss sound and its relationship to poetry, the role of pop culture in the text, and its interactions with misogynoir.1 Using Edouard Glissant’s terminology for language and culture in the Caribbean being an amalgamation of sorts, what he called Antillanité2 and viewing Diggs’s (2013) representation of Blackness through a multicultural lens disrupts the monolithic narrative of Black identity. She invokes a pluralistic perspective on language with her use of Japanese, English and AAVE in the same poem. She also examines the duality of Black identity, what WEB DuBois referred to as double consciousness (DuBois 1961, 3) and alienation exemplifying the “twoness” the “two souls, two thoughts and two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body” (DuBois 1961, 3). -

The Song of the Lark I

HE ONG OF THE ARK T S L BY WILLA CATHER © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2010 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2010 Tantor Media, Inc. -

Lil Baby All of a Sudden Free Mp3 Download ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard

lil baby all of a sudden free mp3 download ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard. ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard zip. “Too Hard” is another 2017 Album by “Lil Baby”. Stream & Download “ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard” “Mp3 Download”. Stream And “Listen to ALBUM: Lil Baby – Too Hard” “fakaza Mp3” 320kbps flexyjams cdq Fakaza download datafilehost torrent download Song Below. 01 Lil Baby – To the Top Mp3 Download 02 Lil Baby – Money Mp3 Download 03 Lil Baby – All of a Sudden (feat. Moneybagg Yo) Mp3 Download 04 Lil Baby – Money Forever (feat. Gunna) Mp3 Download 05 Lil Baby – Best of Me Mp3 Download 06 Lil Baby – Ride My Wave Mp3 Download 07 Lil Baby – Hurry Mp3 Download 08 Lil Baby – Sum More (feat. Lil Yachty) Mp3 Download 09 Lil Baby – Going For It Mp3 Download 10 Lil Baby – Slow Mo Mp3 Download 11 Lil Baby – Trap Star Mp3 Download 12 Lil Baby – Eat Or Starve (feat. Rylo) Mp3 Download 13 Lil Baby – Freestyle Mp3 Download 14 Lil Baby – Vision Clear (feat. Lavish the MDK) Mp3 Download 15 Lil Baby – Dive In Mp3 Download 16 Lil Baby – Stick On Me (feat. Rylo) Mp3 Download. All Of A Sudden. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at $1.49. All Of A Sudden. Copy the following link to share it. You are currently listening to samples. Listen to over 70 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and more than 70 million songs with your unlimited streaming plans. -

Lamorinda Weekly Issue 23 Volume 11

Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2018 • Vol. 11 Issue 23 26,000 copies delivered biweekly to Lamorinda homes & businesses 925-377-0977 wwww.lamorindaweekly.comww.lamorindaweekly.com FREE Windy Margerum shows off her winning medals (left). Margerum in long jump (top right); Monte Upshaw, 1954 (lower right). Photos providedprovided Keeping track of Lamorinda long jumpers By John T. Miller hree generations of track and fi eld stars continue to long jump (‘04 and ‘08) – stays active with private coach- Joy and Grace, along with their other siblings Chip and make news in the Lamorinda area. ing, and Joy’s daughter, Acalanes High School grad Windy Merry, plan to honor their father with a Monte Upshaw T Monte Upshaw, the patriarch of the family, Margerum, is off to a fl ying start at UC Berkeley compet- Long Jump Festival to be held at Edwards Stadium next passed away in July and will be honored next year with ing in track and fi eld. Joy’s eldest daughter Sunny is a for- year. The event is being planned to coincide with the Bru- a long jump festival. His eldest daughter Joy continues to mer Central Coast Section champion long jumper whose tus Hamilton Invitational meet on April 27-28. Proceeds excel in Masters track and fi eld competition worldwide; college career at Berkeley was cut short by an Achilles in- will go to benefi t the UC Berkeley track program. a younger daughter Grace – a two-time Olympian in the jury. ... continued on page A12 Advertising Here's to a happy, healthy and homey new year! 1941 Ascot Drive, Moraga 2 bedrooms 710 Augusta Drive, Moraga 2 bedrooms Community Service B4 + den/2 baths, + den, 2 baths, 1,379 sq.ft. -

Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in the Oedipus Complex

Jenna Davis 1 Beyond Castration: Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in the Oedipus Complex Je=aDavis Critical Theory Swathmore College December 2011 Jenna Davis 2 CHAPTER 1 Argument and Methodology Psychoanalysis was developed by Austrian physician Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of Freud's most celebrated theories was that of the Oedipus complex, which explores the psychic structures that underlie sexual development. In the following chapters I will be examining the Oedipal and preoedipal stages of psychosexual development, drawing out their implicit gendered assumptions with the help of modern feminist theorists and psychoanalysts. I am pursuing a Lacanian reading of Freud, in which the biological roles of mother and father are given structural importance, so that whomever actually occupies these roles is less important than their positional significance. After giving a brief history of the evolution of psychoanalytic theory in the first chapter, I move on in the second chapter to explicate Freud's conception of the Oedipus complex (including the preoedipal stage) and the role of the Oedipal myth, making use of theorist Teresa de Lauretis. In the third chapter, I look at several of Freud's texts on femininity and female sexuality. I will employ Simone de Beauvoir, Kaja Silverman and de Lauretis to discuss male and female investments in femininity and the identities that are open to women. After this, Jessica Benjamin takes the focus away from individuals and incorporates the other in her theory of intersubjectivity. I end chapter three with Helene Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, who all attest to the necessity of symbolic female representation--Cixous proposes a specifically female manner of writing called ecriture feminine, Kristeva introduces the semiotic realm to contend with Lacan's symbolic realm, and Irigaray believes in the need for corporeal Jenna Davis 3 representation for women within a female economy. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Five Star Transcript

Five Star Transcript Timecode Character Dialogue/Description Explanation INT: Car, Night 01:00:30:00 Primo March 24th, 2008, a little boy was born. 01:00:40:00 Sincere Israel Najir Grant, my son. 01:01:00:00 That's my son. 01:01:01:00 You know where I was? Nah, not the hospital bed. 01:01:10:00 Nah not in the waiting room. 01:01:13:00 I was locked the fuck up. 01:01:23:00 Remember gettin' that call, putting the call in I should say. Had a beautiful baby boy, and I wasn't there to greet him when he 01:01:33:00 came into the world. 01:01:36:00 And, um, it's funny. 01:01:40:00 I was released the week after. 01:01:43:00 April 1st, my Pop's birthday. Dialogue Transcript Five Star a film by Keith Miller 1 Five Star Transcript Timecode Character Dialogue/Description Explanation 01:01:48:00 Came home on April Fool's Day, dig that. I remember walking in, into the P's*. Everybody yo Primo, Primo oh, 01:01:56:00 * P’s = projects/housing project shit. 01:02:03:00 Fuck y'all. I want to see my son. 01:02:06:00 Walked up the stairs, I was nervous. 01:02:14:00 Haven't seen my daughter in so long. Open the door, everybody greeting me. Oh welcome home! Welcome 01:02:20:00 home! Yeah it's nice, that that that was sweet. Move! I want to see my son. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently in Music

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 10x The Talent = 1/3 Of The Credit: How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently In Music Meggan Jordan University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Jordan, Meggan, "10x The Talent = 1/3 Of The Credit: How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently In Music" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 946. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/946 10X THE TALENT = 1/3 OF THE CREDIT HOW FEMALE MUSICIANS ARE TREATED DIFFERENTLY IN MUSIC by MEGGAN M. JORDAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 © 2006 Meggan M. Jordan ii ABSTRACT This is an exploratory, qualitative study of female musicians and their experiences with discrimination in the music industry. Using semi-structured interviews, I analyze the experiences of nine women, ages 21 to 56, who are working as professional musicians, or who have worked professionally in the past. I ask them how they are treated differently based on their gender. -

DAWG Tales Lists Honorary Pet Sitting During Your Vacation)

Best Dawg Rescue • www.dawg-rescue.org Spring 2013 Dear Friends, especially if there are other pets in the home. What’s Hope your new year started well and continues that that saying about an ounce of prevention? Better yet, a way now that it’s spring! As for resolutions, we all make precaution that takes a minute but could be a lifesaver. them, break them, and eventually avoid them. However, Our first newsletter of the year reports on the prior here’s one that’s easy to keep and a “win-win” no matter year’s intake and adoptions. In 2012 we adopted out and when you opt to do it: volunteer to help our dogs! took in 52 dogs, a good balance and a lot of work given Why not take your devotion to dogs to the next level the fact that one dog “out” and one dog “in” per week and volunteer at an occasional adoption show? You requires many trips from intake, vetting and adoption can ask for a specific dog, or we can match you with a shows, to home visits and the final placement. However, dog of any size or personality. Worried about falling in it was a “slow” year all around. As for 2013, we’ve had a love with a dog? It happens, but the “pain” turns to joy terrific start, with 23 adoptions and 24 new dogs already. because you help select the future adopter. With spring comes a slowing trend, so we have reduced Our dogs really need your help to become adopted.