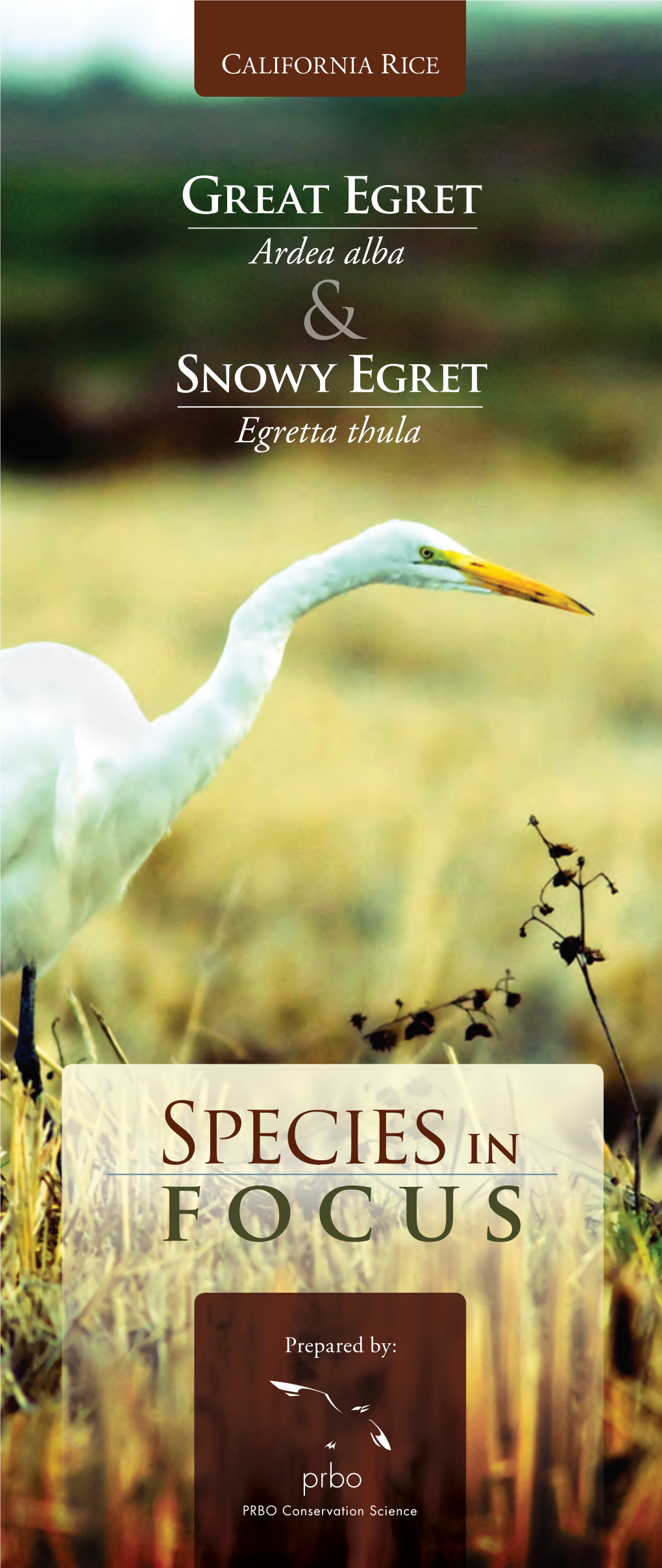

Species in Focus: Great Egret & Snowy Egret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snowy Egret Egretta Thula

Wyoming Species Account Snowy Egret Egretta thula REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S1S2 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: Not ranked STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS The Wyoming Natural Diversity Database has assigned Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) a state conservation rank ranging from S1 (Critically Imperiled) to S2 (Imperiled) because of uncertainty about population trends for this species in Wyoming. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are currently two recognized subspecies of Snowy Egret, which are weakly distinguished by minor size differences: E. t. thula breeds in eastern North America, the Greater Antilles, and throughout South America, while E. t. brewsteri breeds in western North America west of the Rocky Mountains 1, 2. Both subspecies are likely found in Wyoming 3, but this has not been confirmed. Description: Identification of Snowy Egret is possible in the field. It is a medium heron; adults weigh approximately 370 g, range in length from 56–66 cm, and have wingspans of approximately 100 cm 1. Males are slightly larger, but the sexes are otherwise similar in appearance 1. Breeding adults have uniform white plumage with long plumes of delicate feathers on the nape, breast, and lower back that are used in courtship displays; a long S-curved neck; yellow eyes; bright lores that range from dark yellow to red; a long black bill; long black legs; and dark yellow or orange feet 1, 4. -

SNOWY EGRET Egretta Thula Non-Breeding Visitor, Vagrant Monotypic

SNOWY EGRET Egretta thula non-breeding visitor, vagrant monotypic Snowy Egrets breed in most of the contiguous United States and throughout Central and South America (AOU 1998). In the post-breeding season some wander irregularly north to S Canada and SE Alaska, and then withdraw to winter in the s. U.S. and southward. In the Pacific, vagrants have reached Clipperton, the Galapagos, and the Revilligedos Is (Howell et al. 1993, AOU 1998) as well as the Hawaiian Islands (Scott et al. 1983, Pratt et al.1987), where there are four confirmed records. Snowy Egrets and other small white herons and egrets were virtually unknown in the Hawaiian Islands prior to 1950, likely related to decreased source populations resulting from plume hunting during the first third of the century. Several small egrets observed during the mid-1970s through the early 1980s were reported as Snowy Egrets, but Scott et al. (1983) described the similarity in soft-part colors between Snowy Egret and Little Egret of Eurasia, and emphasized the difficulty in separating these in the field (see also AB 36:221). They concluded that an individual reported from Mohouli Pond , Hilo, Hawai'i 15-20 Jan 1975 (E 37:151, 43:79) and 1-2 at Kanaha Pond 5 Dec 1980-7 Apr 1981 were only identifiable as Snowy/Little egrets (cf. Pyle 1977), but that one on O'ahu in 1980 with nuptial plumes (see below) could be confirmed as a Snowy Egret. They also concluded Snowy Egret was more likely than Little Egret to reach Hawaii, since most migrants and vagrants to the Southeastern Islands are North American in origin; however, several observations in 1982-1990 were thought possibly to be Little Egrets. -

Ardea Cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Ardea cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Grey heron, Ardea cinerea. [http://www.google.tt/imgres?imgurl=http://www.bbc.co.uk/lancashire/content/images/2006/06/15/grey_heron, downloaded 14 November 2012] TRAITS. Grey herons are large birds that can be 90-100cm tall and an adult could weigh in at approximately 1.5 kg. They are identified by their long necks and very powerful dagger like bills (Briffett 1992). They have grey plumage with long black head plumes and their neck is white with black stripes on the front. In adults the forehead sides of the head and the centre of the crown are white. In flight the neck is folded back with the wings bowed and the flight feathers are black. Each gender looks alike except for the fact that females have shorter heads (Seng and Gardner 1997). The juvenile is greyer without black markings on the head and breast. They usually live long with a life span of 15-24 years. ECOLOGY. The grey heron is found in Europe, Asia and Africa, and has been recorded as an accidental visitor in Trinidad. Grey herons occur in many different habitat types including savannas, ponds, rivers, streams, lakes and temporary pools, coastal brackish water, wetlands, marsh and swamps. Their distribution may depend on the availability of shallow water (brackish, saline, fresh, flowing and standing) (Briffett 1992). They prefer areas with tall trees for nesting UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour (arboreal rooster and nester) but if trees are unavailable, grey herons may roost in dense brush or undergrowth. -

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2

IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2 Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group Djerba Island, Tunisia, 14th - 18th November 2018 Editors: Jocelyn Champagnon, Jelena Kralj, Luis Santiago Cano Alonso and K. S. Gopi Sundar Editors-in-Chief, Special Publications, IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group K.S. Gopi Sundar, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Luis Santiago Cano Alonso, Co-chair IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Invited Editors for this issue Jocelyn Champagnon, Tour du Valat, Research Institute for the Conservation of Mediterranean Wetlands, Arles, France Jelena Kralj, Institute of Ornithology, Zagreb, Croatia Expert Review Board Hichem Azafzaf, Association “les Amis des Oiseaux » (AAO/BirdLife Tunisia), Tunisia Petra de Goeij, Royal NIOZ, the Netherlands Csaba Pigniczki, Kiskunság National Park Directorate, Hungary Suggested citation of this publication: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) 2019. Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. ISBN 978-2-491451-00-4. Recommended Citation of a chapter: Marion L. 2019. Recent trends of the breeding population of Spoonbill in France 2012- 2018. Pp 19- 23. In: Champagnon J., Kralj J., Cano Alonso, L. S. & Sundar, K. S. G. (ed.) Proceedings of the IX Workshop of the AEWA Eurasian Spoonbill International Expert Group. IUCN-SSC Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group Special Publication 2. Arles, France. INFORMATION AND WRITING DISCLAIMER The information and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors. -

Flamingo ABOUT the GROUP

Flamingo ABOUT THE GROUP Bulletin of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) was established in 1978 at Tour du Valat in France, under the leadership of Dr. Alan Johnson, who coordinated the group until 2004 (see profile at www.wetlands.org/networks/Profiles/January.htm). Currently, the group is FLAMINGO SPECIALIST GROUP coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN- SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. The FSG is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non- scientists) concerned with the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research and conservation worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation amongst these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly IUCN - SSC, Ramsar, WWF International and BirdLife International. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from field surveys to breeding biology, diseases, tracking movements and data management. There are currently 165 members around the world, from India to Chile, and from France to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Assistant Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Mr. Nigel Jarrett Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Tel: +44 (0)1453 891177 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 890827 [email protected] [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. -

Resource-Dependent Weather Effect in the Reproduction of the White Stork Ciconia Ciconia

Resource-dependent weather effect in the reproduction of the White Stork Ciconia ciconia Damijan Denac1 Denac D. 2006. Resource-dependent weather effect in the reproduction of the White Stork Ciconia ciconia. Ardea 94(2): 233–240. Weather affects the breeding success of White Stork Ciconia ciconia, but the effect has not been studied in the context of different food resources or habitat quality. The aim of this study was to determine whether the impact of weather conditions on breeding success was dependent on habitat quality. The effect of weather on reproduction was analysed in two populations that differed significantly in the availability of suitable feeding habitats. Multiple regression analyses revealed that of the weather variables analysed (average temperature and rainfall in April, May and June), rainfall in May and temperature in June explained a sig- nificant part of the variation in numbers of fledged chicks per pair, but only in the population with poorer food resources. The lack of weather influence in the population with richer food resources was tentatively explained by the larger brood sizes. More effective heat conservation in larger broods, and thus lower chick mortality during cold weather, could be the underlying mechanism for the different response to weather in the two populations. Key words: breeding success, Ciconia ciconia, habitat quality, resource dependent weather-effect, White Stork 1National Institute of Biology, Vecv na pot 111, SI–1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION optimal feeding habitats, whereas fields, especially cornfields, are suboptimal (Sackl 1987, Pinowski et The influences of food as a resource and weather al. -

A Year Following Egrets

❚ 10 The Ardeid ❚■ Insights from birds with GPS tags A Year Following Egrets by David Lumpkin o a Great Egret (Ardea alba), Tomales Bay the deployment of our tags, all three Tis full of food, but that food is not always egrets remained near Toms Point in available. Every two weeks, around the full northern Tomales Bay, where we and new moons, the lowest tides and greatest could regularly download data foraging opportunity coincide with the early with the handheld receiver Figure 1. Egret 9 flying over Cypress morning, making breakfast on the bay an easy then eagerly rush back Grove the day after it was captured in affair. During low tides, hundreds of acres of to the office to upload September 2018. intertidal eelgrass are exposed, allowing egrets the data to a computer to stab at herring during spawning events or and see what the birds had been doing. About a to hunt pipefish, which try to wrap themselves month after tagging, suddenly two of the three a freshwater pond at Toms Point. I watched around the egret’s bill to avoid being swal- egrets could no longer be found on Tomales him forage there several times. Though this lowed. As the tide cycle shifts and morning tides Bay. Worried something might have happened pond was well covered by aquatic plants, he was become higher, the eelgrass is exposed for fewer to them, and perplexed that they might leave an consistently able to find small fish, picking them hours per day, reducing foraging opportunities area where they likely had active nests, I drove out from tiny gaps in foliage. -

Roseate Spoonbill Breeding in Camden County: a First State Nesting Record for Georgia

vol. 76 • 3 – 4 THE ORIOLE 65 ROSEATE SPOONBILL BREEDING IN CAMDEN COUNTY: A FIRST STATE NESTING RECORD FOR GEORGIA Timothy Keyes One Conservation Way Brunswick, GA 31520 [email protected] Chris Depkin One Conservation Way Brunswick, GA 31520 [email protected] Jessica Aldridge 6222 Charlie Smith Sr. Hwy St. Marys, GA 31558 [email protected] Introduction We report the northernmost breeding record of Roseate Spoonbill (Platalea ajaja) on the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. Nesting activity has been suspected in Georgia for at least 5 years, but was first confirmed in June 2011 at a large wading bird colony in St. Marys, Camden County, Georgia. Prior to this record, the furthest northern breeding record for Roseate Spoonbill was in St. Augustine, St. John’s County, Florida, approximately 100 km to the south. This record for Georgia continues a trend of northward expansion of Roseate Spoonbill post-breeding dispersal and breeding ranges. Prior to the plume-hunting era of the mid to late 1800s, the eastern population of Roseate Spoonbill was more abundant and widespread than it is today (Dumas 2000), breeding across much of south Florida. Direct persecution and collateral disturbance by egret plume hunters led to a significant range contraction between 1850 and the 1890s (Allen 1942), limiting the eastern population of Roseate Spoonbills to a few sites in Florida Bay by the 1940s. A low of 15 nesting pairs were documented in 1936 (Powell et al. 1989). By the late 1960s, Roseate Spoonbills began to expand out of Florida Bay, slowly reclaiming some of the territory they had lost. -

Great Egret Ardea Alba

Great Egret Ardea alba Joe Kosack/PGC Photo CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the great egret is listed state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migra- tory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: The Pennsylvania Game Commission counts active great egret (Ardea alba) nests in every known colony in the state every year to track changes in population size. Since 2009, only two nesting locations have been active in Pennsylvania: Kiwanis Lake, York County (fewer than 10 pairs) and the Susquehanna River’s Wade Island, Dauphin County (fewer than 200 pairs). Both sites are Penn- sylvania Audubon Important Bird Areas. Great egrets abandoned other colonies along the lower Susque- hanna River in Lancaster County in 1988 and along the Delaware River in Philadelphia County in 1991. Wade Island has been surveyed annually since 1985. The egret population there has slowly increased since 1985, with a high count of 197 nests in 2009. The 10-year average count from 2005 to 2014 was 159 nests. First listed as a state threatened species in 1990, the great egret was downgraded to endan- gered in 1999. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS: Great egrets are almost the size of a great blue heron (Ardea herodias), but white rather than gray-blue. From bill to tail tip, adults are about 40 inches long. The wingspan is 55 inches. The plumage is white, bill yellowish, and legs and feet black. Commonly confused species include cattle egret (Bubulus ibis), snowy egret (Egretta thula), and juvenile little blue herons (Egretta caerulea); however these species are smaller and do not nest regularly in the state. -

Snowy Egret Egretta Thula One of California's Most Elegant Birds, The

Herons and Bitterns — Family Ardeidae 133 Snowy Egret Egretta thula One of California’s most elegant birds, the Snowy Egret frequents both coastal and inland wetlands. Since the 1930s, when it recovered from persecution for its plumes, it has been common in fall and winter. Since 1979, it has also established an increasing num- ber of breeding colonies. Yet, in contrast to the Great Egret, the increase in Snowy Egret colonies has not been accompanied by a clear increase in the Snowy’s numbers. Though dependent on wetlands for forag- ing, the Snowy Egret takes advantage of humanity, from nesting in landscaping to following on the heels of clam diggers at the San Diego River mouth, snap- ping up any organisms they suck out of the mud. Breeding distribution: The first recorded Snowy Egret colonies in San Diego County were established at Buena Vista Lagoon in 1979 (J. P. Rieger, AB 33:896, 1979) and Photo by Anthony Mercieca in the Tijuana River valley in 1980 (AB 34:929, 1980). By 1997 these were no longer active, but during the atlas Two of the largest colonies lie near San Diego and period we confirmed nesting at eight other sites. Because Mission bays. The colony on the grounds of Sea World, Snowy Egrets often hide their nests in denser vegetation behind the Forbidden Reef exhibit (R8), was founded than do the Great Egret and Great Blue Heron, assessing in 1991 and contained 42 nests and fledged 44 young in the size of a Snowy Egret colony is more difficult than for 1997 (Black et al. -

Snowy Egret Egretta Thula Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata an Adult Snowy Egret Is 20 to 27 Inches Long

snowy egret Egretta thula Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata An adult snowy egret is 20 to 27 inches long. It is a Class: Aves white-feathered, small, thin egret. It has a yellow Order: Pelecaniformes patch between its eye and black bill, but during the breeding season the patch is red. The legs are black, Family: Ardeidae and the feet are yellow. ILLINOIS STATUS endangered, native BEHAVIORS The snowy egret is a rare migrant through Illinois The endangered status is due to the massive number and a summer resident in southwestern Illinois of snowy egrets that were killed in the late 1800s for along the Mississippi River. It winters from the their feathers (plume hunting). The snowy egret was southern coastal United States to South America. never very common in Illinois before this period of The snowy egret lives near marshes, lakes, ponds, plume hunting and has not recovered well since. sloughs, flooded fields and lowland thickets or forests. This bird feeds mainly on crayfish, fishes, frogs and insects. It is active in seeking prey and may be seen fluttering over the water or running through the water to catch food. This bird spends much time wading along the water's edge. Like the other herons, its neck is held in an "S" formation during flight with its legs trailing straight out behind its body. It nests with other snowy egrets in a tree colony, called a rookery. Nests contain three to four blue-green eggs. The call of the snowy egret is "wulla-wulla-wulla." ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management.