Great Cities New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

⁄Sþç}˛Ðn‚9Ô£ Rð˘¯Þ

559191 bk BEACH EU 25/05/2004 04:34pm Page 16 To her whose voice and loving hands fl Though I take the wings of morning, Op. 152 Can soothe our heart’s unrest, (1941) MERICAN LASSICS We bring these flowers, fragrant, fair, Though I take the wings of morning A C Our life her love hath blest! To the utmost sea, MAY FLOWERS Lyrics by Ana Mulford Addison Moody Yet my soul hath no sojourning Music by Amy Beach g1933 A.P. SCHMIDT CO. To outdistance Thee. Copyright Renewed and Assigned to SUMMY-BIRCHARD AMY BEACH MUSIC, a division of SUMMY-BIRCHARD INC. Though I climb to highest heaven, All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission of Warner Bros. ’Tis Thy dwelling high; Publications U.S. Inc. Though to death’s dark chamber given, Thou art standing by. fi I sought the Lord, Op. 142 (1937) Songs I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew If I say, the darkness hides me, He moved my soul to seek Him, seeking me; Turns my night to day; It was not I that found, O Saviour true; For with Thee no dark can find me, No, I was found of Thee. Shadows must away! The Year’s at the Spring Thou didst reach forth Thy hand and mine enfold; Even so, Thy hand shall lead me, I Sought the Lord I walked and sank not on the stormy sea; Flee Thee as I will; ’Twas not so much that I on Thee took hold, And Thy strong right arm shall hold me: As Thou, dear Lord, on me. -

Firebird, Winger & Watts

FIREBIRD, WINGER & WATTS A E G I S CLASSICAL SERIES S C I E N C E S FOUNDATION EST. 2013 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, AT 7 PM | FRIDAY & SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 15 & 16, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY GIANCARLO GUERRERO, conductor THANK YOU TO ANDRÉ WATTS, piano OUR PARTNER CLAUDE DEBUSSY Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune SERIES PRESENTING PARTNER [Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun] EDWARD MACDOWELL Concerto No. 2 in D minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 23 I. Larghetto calmato II. Presto giocoso III. Largo - Molto allegro INTERMISSION KIP WINGER Conversations with Nijinsky Chaconne de feu Waltz Solitaire Souvenir Noir L’Immortal IGOR STRAVINSKY Suite from The Firebird (1919 revision) I. Introduction and Dance of the Firebird II. Dance of the Princesses III. Infernal Dance of King Kastchei IV. Berceuse A E G I S V. Finale S C I E N C E S FOUNDATION EST. 2013 INCONCERT 21 TONIGHT’S CONCERT AT A GLANCE CLAUDE DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun • Inspired by French writer Stéphane Mallarmé’s 1876 poem, Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of the Faun is a single-movement piece in which Debussy evokes the source material through lush woodwind colors. The iconic flute theme gently sets the scene for an impressionistic musical tableau of a faun playing the panpipes in the woods. The metric ambiguity of the piece, along with sparing use of brass and percussion, adds to the distinctive feel. • The composer’s musical interpretation pleased Mallarmé, who praised the work, saying, “The music prolongs the emotion of the poem and fixes the scene more vividly than colors could have done.” EDWARD MACDOWELL Piano Concerto No. -

Music of Samuel Barber

July 24, 2016 :: Las Puertas :: Albuquerque :: #418 Music of Samuel Barber (1910–1981) 6-year-old Moxie is attending her A performance to share the music of Samuel Barber, composer of the opera very first Chatter concert. Vanessa, performed for the first time this summer at The Santa Fe Opera. G-Ma and Poppa love Moxie. Rebecca Krynski Cox soprano | Jarrett Ott baritone Robert Tweten piano Del Sol String Quartet featuring Benjamin Kreith, Rick Shinozaki violin Charlton Lee viola | Kathryn Bates cello CHATTER SUNDAY Three Songs Opus 10 (1936) Sunday, July 31 @ 10:30am III I Hear an Army Peter Gilbert Intermezzi, world premiere Love at the Door (1934) Philip Glass Etudes No. 3, 2, 8, and 9 Four Songs Opus 13 (1940) III Sure on this Shining Night Aaron Jay Kernis Air for Violin and Piano Frederic Rzewski ABQ Slam Team poets Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues Emanuele Arciuli piano Dover Beach Opus 3 (1931) David Felberg violin String Quartet Opus 11 (1936) Rich Boucher poet I Molto allegro e appassionata II Molto adagio (attacca) CHATTER SUNDAY III Molto allegro (come prima) 50 weeks every year at 10:30am Las Puertas, 1512 1st St NW, Abq Celebration of Silence :: Two Minutes Subscribe to eNEWS at ChatterABQ.org Videos at YouTube.com/ChatterABQ Share/follow us on social media: Hermit Songs Opus 29 (1953) · facebook.com/ChatterABQ I At Saint Patrick’s Purgatory VI Sea-Snatch · twitter.com/ChatterABQ II Church Bells at Night VII Promiscuity · instagram.com/ChatterABQ III St. Ita’s Vision VIII The Monk and His Cat Tix at ChatterABQ.org/boxoffice IV The Heavenly Banquet IX The Praises of God V The Crucifixion X The Desire of Hermitage Chatter is grateful for the support of the National Endowment for the Arts About Vanessa by Samuel Barber :: A Company Premiere Sung in English with Opera Titles in English and Spanish. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: the Nature of Music May, 2021 Dear Fellow Educators

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: The Nature of Music May, 2021 Dear Fellow Educators, As spring arrives each year, I am reminded of the powerful relationship between nature and music. Both start as a single seed (or note!) and go on to blossom into something beautiful. Each plant, like each piece of music, is both a continuation of what came before and the start of something new. With Earth Day just a few weeks before our May concert, we wanted to use this Youth Concert as a way to explore and honor our planet through the lens of classical music. During our program, The Nature of Music, you and your students will hear music inspired by rivers, wildflowers, birds, and a busy bumblebee! Musicians have often used the earth’s natural beauty as inspiration for their music, and they try to use musical sounds to paint a picture for our ears, much like an artist would use different colors to paint a picture for our eyes. Each lesson will help your students explore and experience this connection. This concert will be offered virtually (available May 16 – June 4) but we are also accepting reservations for in-person viewing! Our two back-to-back concerts will be on Wednesday, May 5 at 10am and 11:30am. Please contact me or email my colleague in sales, Sabrina Siggers (contact information below), to reserve your classes reservation. You can see up-to-date Meyerson safety protocol below. We humans have a responsibility to respect and care for animals, plants, and the earth’s natural resources. -

Colorado-Wyoming District Stephen Dilts Karen Mohr Chris Mohr Lynn Harrington Committee

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON COLO≤ DO-WYOMING DISTRICT AUDITIONS SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifnals. National fnalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifnals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each frst-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifnals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met. -

This Album Presents American Piano Music from the Later Part of the Nineteenth Century to the Beginning of the Twentieth

EDWARD MacDOWELL and Company New World Records 80206 This album presents American piano music from the later part of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. Chronologically it ranges from John Knowles Paine’s Fuga Giocosa, published in 1884, to Henry F. Gilbert’s Mazurka, published in 1902. The majority are from the nineties, a time of great prosperity and self-satisfaction in a nation of philanthropists and “philanthropied,” as a writer characterized it in The New York Times. Though the styles are quite different, there are similarities among the composers themselves. All were pianists or organists or both, all went to Europe for musical training, and all dabbled in the classical forms. If their compatriots earlier in the nineteenth century wrote quantities of ballads, waltzes, galops, marches, polkas, and variations on popular songs (New World Records 80257-2, The Wind Demon), the present group was more likely to write songs (self-consciously referred to as “art songs”) and pieces with abstract titles like prelude, fugue, sonata, trio, quartet, and concerto. There are exceptions. MacDowell’s formal works include two piano concertos, four piano sonatas, and orchestra and piano suites, but he is perhaps best known for his shorter character pieces and nature sketches for piano, such as Fireside Tales and New England Idyls (both completed in 1902). Ethelbert Nevin was essentially a composer of songs and shorter piano pieces, most of them souvenirs of his travels, but he, too, worked in the forms that had become most prestigious in his generation. The central reason for the shift away from dance-inspired and entertainment pieces to formal compositions was that American wealth created a culture that created a musical establishment. -

WORLD YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Andreas Delfs, Conductor

99th Program of the 88th Season Interlochen, Michigan * WORLD YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Andreas Delfs, conductor with guest soloist James Ehnes, violin Sunday, July 19, 2015 8:00pm, Kresge Auditorium 7:00pm pre-concert talk Violin Concerto, Op. 14 .................................................................................... Samuel Barber Allegro (1910-1981) Andante Presto in moto perpetuo James Ehnes, violin Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 .................................................................... Richard Strauss Einleitung, oder Sonnenaufgang (Introduction, or Sunrise) (1864-1949) Von den Hinterweltlern (Of Those in Backwaters) Von der großen Sehnsucht (Of the Great Longing) Von den Freuden und Leidenschaften (Of Joys and Passions) Das Grablied (The Song of the Grave) Von der Wissenschaft (Of Science and Learning) Der Genesende (The Convalescent) Das Tanzlied (The Dance Song) Nachtwandlerlied (Song of the Night Wanderer) The audience is requested to remain seated during the playing of the Interlochen Theme and to refrain from applause upon its completion. * * * PROGRAM NOTES Samuel Barber, Violin Concerto, Op. 14 In comparison to his colleagues Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and George Gershwin, American composer Samuel Barber’s unique compositional voice may be the most cosmopolitan. His sophisticated Romanticism has a universal quality that is related to the European tradition and yet remains distinctly American. Perhaps this is why his soaring lyricism, rhythmic complexity, and harmonic language appealed to early–and mid–20th- century luminaries such as Fritz Reiner, Arturo Toscanini, Vladimir Horowitz, and Dimitri Mitropoulos. He achieved success early in his career, writing his first opera at age 10, and, at 14, entering Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, where he excelled in composition, piano, and voice. At 18, he won the Joseph H. -

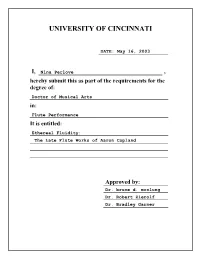

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961). -

SAMUEL BARBER Evening During Term in the College Chapel and Presents an Annual Concert Series

559053bk Barber 15/6/06 9:51 pm Page 5 Choir of Ormond College, University of Melbourne Deborah Kayser Deborah Kayser performs in areas as diverse as ancient Byzantine chant, French and German Baroque song and In June and July of 2005 the Choir of Ormond College gave its eleventh international concert tour, visiting classical contemporary music, both scored and improvised. Her work has led her to tour regularly both within AMERICAN CLASSICS Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Poland and Italy. Other tours have included New Zealand, Singapore, Japan, Australia, and internationally to Europe and Asia. She has recorded, as soloist, on numerous CDs, and her work is Holland, England, Scotland, Switzerland and Belgium. These tours have received outspoken praise from the public frequently broadcast on ABC FM. As a member of Jouissance, and the contemporary music ensembles Elision and and critics alike. The choir was formed by its Director; Douglas Lawrence, Master of the Chapel Music, in 1982. Libra, she has performed radical interpretations of Byzantine and Medieval chant, and given premières of works There are 24 Choral Scholars: ten sopranos, four altos, four tenors, and six basses. The choir sings each Sunday written specifically for her voice by local and overseas composers. Her performance highlights include works by SAMUEL BARBER evening during term in the College chapel and presents an annual concert series. Each year a number of outside composers Liza Lim, Richard Barrett and Chris Dench, her collaboration with bassist Nick Tsiavos, and oratorio and engagements are undertaken. These have included concerts for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, Musica choral works with Douglas Lawrence.