A Georgian Suburb Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queens Crescent, Kentish Town

Queens Crescent, Kentish Town NW5 Internal Page1 Single Pic Inset A beautiful 4 bedroom 2 bathroom family home on a quiet tree lined Crescent conveniently located between Hampstead Heath and Kentish Town. FirstThis familyparagraph, home editorialhas been style, refurbished short, consideredto a high standard headline by the benefitscurrent owners of living and here. comprises One or two on thesentences ground thatfloor conveyof an open what you would say in person. plan reception room with a fireplace, fully integrated eat-in Secondkitchen diner,paragraph, private additional garden and details guest of W/C.note aboutOn the the first floor are property.2 double Wordingbedrooms to andadd avalue large and family support bathroom, image whilst selection. on the Temsecond volum floor is aresolor 2 furthersi aliquation double rempore bedrooms puditiunto (1 with an qui en-suite utatis adit,bathroom). animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. ThirdThe house paragraph, has a additional loft that could details be ofconverted note about subject the property. to the Wordingnecessary to planningadd value permissions. and support image selection. Tem volum is solor si aliquation rempore puditiunto qui utatis adit, animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. 4XXX2 1 X GreatQueens Missenden Crescent is1.5 located miles, London 0.3 miles Marlebone to Chalk Farm 39 minutes, AmershamUnderground 6.5 Station miles, M40 (Northern J4 10 miles,Line) and Beaconsfield 0.4 miles to11 Kentishmiles, M25Town j18 West 13 miles, Station. Central It is also London within 36 easy miles reach (all distances of Hampstead and timesHeath, are Belsize approximate). -

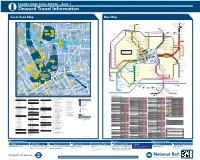

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1

245 EVERSHOLT STREET London NW1 Freehold Property For Sale Well let restaurant and first floor flat situated in the Euston Regeneration Zone Building Exterior 245 EVERSHOLT STREET Description 245 Eversholt Street is a period terraced property arranged over ground, lower ground and three upper floors. It comprises a self-contained restaurant unit on ground and lower ground floors and a one bedroom residential flat at first floor level. The restaurant is designed as a vampire themed pizzeria, with a high quality, bespoke fit out, including a bar in the lower ground floor. The first floor flat is accessed via a separate entrance at the front of the building and has been recently refurbished to a modern standard. The second and third floor flats have been sold off on long leases. Location 245 Eversholt Street is located in the King’s Cross and Euston submarket, and runs north to south, linking Camden High Street with Euston Road. The property is situated on the western side of the north end of Eversholt Street, approximately 100 metres south of Mornington Crescent station, which sits at the northern end of the street. The property benefits from being in walking distance of the amenities of the surrounding submarkets; namely Camden Town to the north, King’s Cross and Euston to the south, and Regent’s Park to the east. Ground Floor Communications The property benefits from excellent transport links, being situated 100m south of Mornington Crescent Underground Station (Northern Line). The property is also within close proximity to Camden Town Underground Station, Euston (National Rail & Underground) and Kings Cross St Pancras (National Rail, Eurostar and Underground). -

Life Expectancy

HEALTH & WELLBEING Highgate November 2013 Life expectancy Longer lives and preventable deaths Life expectancy has been increasing in Camden and Camden England Camden women now live longer lives compared to the England average. Men in Camden have similar life expectancies compared to men across England2010-12. Despite these improvements, there are marked inequalities in life expectancy: the most deprived in 80.5 85.4 79.2 83.0 Camden will live for 11.6 (men) and 6.2 (women) fewer years years years years years than the least deprived in Camden2006-10. 2006-10 Men Women Belsize Longer life Hampstead Town Highgate expectancy Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Camden Town with Primrose Hill St Pancras and Somers Town Hampstead Town Camden Town with Primrose Hill Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Belsize West Hampstead Regent's Park Bloomsbury Cantelowes King's Cross Holborn and Covent Garden Camden Camden Haverstock average2006-10 average2006-10 Gospel Oak St Pancras and Somers Town Highgate Cantelowes England England Haverstock 2006-10 Holborn and Covent Garden average average2006-10 West Hampstead Regent's Park King's Cross Gospel Oak Bloomsbury Shorter life Kentish Town Kentish Town expectancy Kilburn Kilburn Note: Life expectancy data for 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 90 88 86 84 82 80 78 76 74 72 70 wards are not available for 2010-12. Life expectancy at birth (years) Life expectancy at birth (years) About 50 Highgate residents die Since 2002-06, life expectancy has Cancer is the main cause of each year2009-11. -

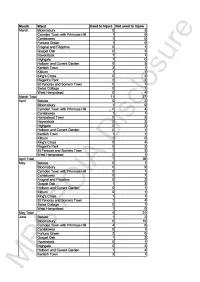

Month Ward Used to Injure Not Used to Injure March Bloomsbury 0 3

Month Ward Used to Injure Not used to injure March Bloomsbury 0 3 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 1 5 Cantelowes 1 0 Fortune Green 1 0 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 1 Gospel Oak 0 2 Haverstock 1 1 Highgate 1 0 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 3 1 Kilburn 1 1 King's Cross 0 2 Regent's Park 2 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 0 1 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 0 4 March Total 11 27 April Belsize 0 2 Bloomsbury 1 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 4 Cantelowes 1 1 Hampstead Town 0 2 Haverstock 2 3 Highgate 0 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kentish Town 1 1 Kilburn 1 0 King's Cross 0 4 Regent's Park 0 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 West Hampstead 0 1 April Total 7 36 May Belsize 0 1 Bloomsbury 0 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 1 Cantelowes 0 7 Frognal and Fitzjohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 1 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kilburn 0 1 King's Cross 1 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 4 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 1 0 May Total 4 31 June Belsize 1 2 Bloomsbury 0 1 0 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 4 6 Cantelowes 0 1 Fortune Green 2 0 Gospel Oak 1 3 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 2 Holborn and Covent Garden 1 4 Kentish Town 3 1 MPS FOIA Disclosure Kilburn 2 1 King's Cross 1 1 Regent's Park 2 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 Swiss Cottage 0 2 West Hampstead 0 1 June Total 18 39 July Bloomsbury 0 6 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 5 1 Cantelowes 1 3 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 2 0 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 4 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 1 0 King's Cross 0 3 Regent's Park 1 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 0 Swiss Cottage 1 2 West -

Camden Town High Street London, UK

Camden Town High Street Lively Living on London, UK Camden High Street Deanna Goldy | Claire Harlow Colorful and funky, Camden Town High Street draws around 300,000 visitors each weekend. Camden Town High Street is located in Camden, a bor- ough just east of the heart of London. Camden is among the most diverse neighbor- hoods in London and High Street is well-known and loved for its artisans, unique shops, lively markets and alternative culture. Left Top: Camden High Street, from Google Street View Left Bottom: Vicinity of Greater London, from cityoflond.gov.uk Right: Camden High Street and immediate context, from Google Maps CAMDEN TOWN, LONDON “Working together strengthens and promotes a sense of community.” -Camden Together Neighborhood Character Ethnic Diversity: 27% non-white (Black African, Bangladeshi, Indian, Black Caribbean Chinese among others), 20% non-British white, 53% British white Languages spoken: more than 120 languages spoken including English, Bengali, Sylheti, Somali, Albanian, Arabic, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Lingala Historic preservation: 39 Conservation Areas and over 5,600 structures and buildings listed as architectural or historical interest Religion: 47% Christian, 12% Muslim, 6% Jewish, 4% Buddhist, Hindu and other, 22% non-religious, 10% no response to question Social Deprivation: 66% “educated urbanites”, 29% “inner city adversity” Famous residents of Camden Town: George Orwell, Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, photo credit http-_k43.pbase.com_u44_louloubelle_large_28774912. and Liam Gallagher, lead -

Bellblue Portfolio

Bellblue Portfolio A portfolio of mainly income-producing HMOs, and mixed-use retail & residential buildings all situated within affluent North & North West London suburbs including Kensal Rise, Kilburn, Willesden, Stroud Green and Camden. Available as a portfolio or individually. Opportunities to increase the rental income and add value by way of letting of the current vacant units, refurbishment & modernisation, implementing existing planning consents & obtaining new planning consents (STP). Portfolio Schedule Property Description Income PA ERV Guide Price Gross Yield 26 Chamberlayne Retail & 7 studio £91,296 £116,000 £1,450,000 6.30% Road, Kensal Rise, flats above (Reversionary NW10 3JD Yield 8.0%) 76 Chamberlayne Retail with 3 £73,224 £80,000 £1,275,000 5.74% Road, Kensal Rise, studio & 1 x2-bed (Reversionary NW10 3JJ flats above Yield 6.27%) 88 Chamberlayne HMO – 8 studio Vacant £123,000 £1,525,000 *subject to Road, Kensal Rise, flats with PP to refurb/build NW10 3JL extend costs 112 Chamberlayne Retail with 4 £112,360 £136,000 £1,825,000 6.16% Road, Kensal Rise, studio & 4 1-bed (Reversionary NW10 3JP flats above Yield 7.45%) 7 Clifford Gardens, HMO – 5 studio & £72,936 £107,000 £1,500,000 4.86% Kensal Rise, NW10 2 1-bed flats above (1 unit vacant) (Reversionary 5JE Yield 7.13%) 17 St Pauls Avenue, HMO – 6 studio & £96,180 £123,000 £1,550,000 6.21% Willesden, NW2 5SS 2 1-bed flats above (Reversionary Yield 7.94%) 3 Callcott Road, HMO – 8 studio £95,868 £123,000 £1,595,000 6.01% Kilburn, NW6 7EB flats above (Reversionary Yield 7.71%) -

Camden Profile

Camden Demographic Profile 2007 Camden Profile Link to Demographic Databook June 2021 Overall Size and Composition1 are from overseas. 28% of students live in uni- Comprising almost 22 square kilometres in the versity halls of residence or properties; while heart of London, Camden is a borough of di- 39% reside in the area south of Euston Road3. versity and contrasts. Business centres such as Holborn, Euston and Tottenham Court The latest ‘official’ estimate of Camden's resi- Road contrast with exclusive residential dis- dent population is 279,500 at mid-20204. This tricts in Hampstead and Highgate, thriving Bel- is the nationally comparable population esti- size Park, the open spaces of Hampstead mate required for government returns and na- Heath, Parliament Hill and Kenwood, the tionally comparable performance indicators. youthful energy of Camden Town, subdivided houses in Kentish Town and West Hamp- For overall strategy and for planning stead, as well as areas of relative deprivation. services, Camden uses the GLA demo- graphic projections – See Future Change The Council has designated 40 Conservation in Population on p2). Areas that cover approximately half the bor- ough, while more than 5,600 buildings and ONS estimates show that of our neighbours, structures are listed as having special archi- Barnet and Brent have larger populations; Ha- tectural or historic interest. Camden is well ringey, Westminster, Islington and the City are served by public transport, including three smaller. Camden is just a fragment of Greater main-line railway stations (St Pancras, King’s London, occupying only 1.4% by area – mak- Cross and Euston); and St Pancras Interna- ing it London’s 8th smallest borough by area, tional; with extensive bus, tube and suburban but 5th highest by population density (128 per rail networks – soon to include the Crossrail hectare). -

Kentish Town East Children's Centre Weekly Programme and Activity

Kentish Town East Children’s Centre Weekly Programme and Activity Timetable Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Fun for all Fun for all Baby play Midwifery Midwifery (drop-in for under 5s) (drop-in for under 5s) (drop-in for under 1s) Antenatal appointment only Antenatal appointment only 9:30-11:30am 9:30-11:30am 10am-12pm Call 020 3447 9567 for more Call 020 3447 9567 for more Agar Children’s Centre Agar Children’s Centre Agar Children’s Centre information information 9am-2pm 9am-2pm Agar Children’s Centre Agar Children’s Centre Rhyme time Rhyme time Child and Baby Health Hub Baby Feeding Drop-in (term-time only) (term-time only) (walk in clinic) 10am-12pm 11am-11:30am 10.30am-11:00am 9:30-11:30am Agar Children’s Centre Highgate Library Kentish Town Library Kentish Town Health Centre Baby play Child health clinic Singing stories Toddler time (drop-in for under 1s) (1st and 3rd Tuesdays in the (term-time only) (drop in for under 2’s) 1:30-3:30pm month) 2-3pm 10am-12pm Agar Children’s Centre 1:30-3:30pm Highgate Library Agar Children’s Centre Agar Children’s Centre Young parents together (drop-in for parents under 25) 1-3pm Harmood Children’s Centre If you would like more information please contact Agar Children’s Centre on 020 7974 4789 Kentish Town East and West Weekly Programme and Activity Timetable (please note some drop-ins may charge for attendance. These drop-ins are not funded by Camden Council) Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Busy tots learn lots Under 5s drop-in Movers and shakers Under 5s drop-in Busy tots learn -

First Floor, 89-91 Bayham Street, , LONDON

Self Contained Offices To Let - Camden Town NW1 To let as a whole or as two separate office suites First Floor, 89-91 Bayham Street, LONDON, NW1 0AG Area Net Internal Area: 209 sq.m. (2,248 sq.ft.) Rent £40,000 to £75,000 per annum (approx. £3,333 to £6,250 monthly) subject to contract Property Description The property comprises self contained offices, which are situated on the first floor of a three storey mixed use building. The property has a net internal area of 208.93 sq m (2,249 sq ft). The property is capable of being let in two separate suites, with each configured to a mix of open plan accommodation and partitioned offices / meeting rooms. Each suite benefits from central heating, perimeter trunking, air conditioning, good natural light and kitchen & WC facilities. Key Considerations: > New lease(s) available > Capable of being let in two separate suites of 1,058 sq.ft and 1,191 sq.ft > Vibrant Camden Town location > Excellent transport communications > 250m to Camden Town London Underground Station > 400m to Mornington Crescent London Underground Station Accommodation Area sq.m. Area sq.ft. Comments Right suite 98.27 1,057 Left suite 110.65 1,191 https://www.gilmartinley.co.uk/properties/to-rent/offices/camden/london/nw1/29011 Our ref: 29011 Self Contained Offices To Let - Camden Town NW1 To let as a whole or as two separate office suites Property Location The property is located in the heart of Camden Town on the West side of Bayham Street; a one-way street running immediately parallel with Camden High Street. -

CAMDEN LOCK QUARTER Morrisons, Chalk Farm Road, Camden, NW1 8AA

CAMDEN LOCK QUARTER Morrisons, Chalk Farm Road, Camden, NW1 8AA A SIGNIFICANT CENTRAL LONDON DEVELOPMENT PROMOTION OPPORTUNITY Overview OVERVIEW • A unique Central London Planning Promotion opportunity • Substantial Freehold and Long Leasehold site extending to circa. 3.2 Hectares (circa. 8 Acres) • Located within the heart of Camden Town • A potential wholesale redevelopment site with opportunity to maximise site bulk and massing • Suitable for a range of mixed uses, including Residential and Retail, subject to gaining the necessary consents • An opportunity to work alongside one of Britain’s most established supermarket brands, Wm Morrison Supermarkets, to promote the site and unlock significant value. CAMDEN LOCK IS SITUATED WITHIN THE CENTRAL LONDON BOROUGH OF CAMDEN, LOCATED APPROXIMATELY TWO MILES TO THE NORTH OF LONDON’S WEST END LOCATION Location Camden Town is a vibrant part of London and is globally renowned for its markets, independent fashion, music and entertainment venues. It is home MILLIONS OF VISITORS ARE to a range of businesses, small and large, notably in the media, cultural and creative sectors attracted by its unique atmosphere. DRAWN TO CAMDEN EACH Camden is considered to be one of the major creative media and advertising YEAR FOR ITS THRIVING hubs within London. It has a strong business reputation and is a magnet to software consultancies, advertising firms and publishing houses. It is also MARKETS AND FAMOUS considered a key linchpin in the Soho – Clerkenwell media triangle. ENTERTAINMENT VENUES. Approximately 30,000 full time students live in the Borough of Camden, attracted by the large number of colleges and universities within close Unlike shopping areas such as Oxford Street and Regent Street which proximity. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them.