THE MISCELLANEOUS MEANING of GANGSTA RAP in 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners

Published: Nzinga, K.L.K., & Medin, D.L. (2018). The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 312-342. http://booKsandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/15685373-12340033 The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners Kalonji L.K. NZINGA Douglas L. MEDIN Northwestern University A Cross-cultural approach to moral psychology starts from researchers withholding judgments about universal right and wrong and instead exploring community members’ values and what they subjeCtively perCeive to be moral or immoral in their loCal Context. This study seeks to identify the moral ConCerns that are most relevant to listeners of hip- hop music. We use validated psyChologiCal surveys inCluding the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek 2009) to assess whiCh moral ConCerns are most central to hip-hop listeners. Results show that hip-hop listeners prioritize concerns of justiCe and authentiCity more than non-listeners and deprioritize ConCerns about respeCting authority. These results show that the ConCept of the “good person” within the hip-hop subculture is fundamentally a person that is oriented towards soCial justiCe, rebellion against the status quo, and a deep devotion to keeping it real. Results are followed by a disCussion of the role that youth subCultures have in soCializing young people to prioritize Certain virtues over others as they develop their moral identity. 1. Introduction Many AmeriCan rappers inCluding KendriCk Lamar (2010), Snoop Dogg (2015), and Busta Rhymes (2006) have delivered the following CatCh phrase in their lyriCs: “You Can take me out the hood, but you Can’t take the hood out of me.” They proClaim that there are Certain aspeCts of the “hood” lifestyle and value system that, onCe they are part of you, direCt how you perCeive the world and behave in it. -

Death Row Records

The New Kings of Hip-Hop Death Row Records “You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge.” —N.W.A. Contents Letter from the Director ................................................................................................... 4 Mandate .......................................................................................................................... 5 Background ...................................................................................................................... 7 Topics for Discussion ..................................................................................................... 10 East Coast vs. West Coast .................................................................................... 10 Internal Struggles................................................................................................. 11 Turmoil in Los Angeles ........................................................................................ 12 Positions ........................................................................................................................ 14 Letter from the Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS XII! I am a part of the class of 2022 here at Washington University in St. Louis, and I’ll be serving as your director. Though I haven’t officially declared a major yet, I’m planning on double majoring in political science and finance. I’ve been involved with Model UN since my freshman year of high school, and I have been an active participant ever since. I am also involved -

The Endless Fall of Suge Knight He Sold America on a West Coast Gangster Fantasy — and Embodied It

The Endless Fall of Suge Knight He sold America on a West Coast gangster fantasy — and embodied it. Then the bills came due BY MATT DIEHL July 6, 2015 Share Tweet Share Comment Email This could finally be the end of the road for Suge Knight, who helped bring West Coast gangsta rap to the mainstream. Photo illustration by Sean McCabe On March 20th, inside the high-security wing of Los Angeles' Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center, the man once called "the most feared man in hip-hop" is looking more like the 50-year-old with chronic health issues that he is. Suge Knight sits in shackles, wearing an orange prison jumpsuit and chunky glasses, his beard flecked with gray, listening impassively. It's the end of the day's proceedings, and Judge Ronald S. Coen is announcing the bail for Knight, who is facing charges of murder, attempted murder and hit-and-run: "In this court's opinion, $25 million is reasonable, and it is so set." A gasp erupts from Knight's row of supporters — some of whom sport red clothing or accessories, a color associated with the Bloods and Piru street gangs. The most shocked are Knight's family, who have attended nearly all of his court dates: his parents, along with his fiancee, Toilin Kelly, and sister Karen Anderson. "He's never had a bail like that before!" Anderson exclaims. SIDEBAR 30 Most Embarrassing Rock-Star Arrests » As attendees exit and Knight is escorted out by the bailiffs, Knight's attorney Matthew Fletcher pleads with Coen to reconsider. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

'Troublesome' Voices

‘TROUBLESOME’ VOICES Ph.D. Thesis – M. Smith McMaster University – English & Cultural Studies ‘TROUBLESOME’ VOICES: REPRESENTATIONS OF BLACK WOMANHOOD IN STREET LITERATURE AND HIP-HOP MUSIC By MARQUITA R. SMITH, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Marquita R. Smith, August 2015 ii Ph.D. Thesis – M. Smith McMaster University – English & Cultural Studies DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) McMaster University (English & Cultural Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: ‘Troublesome’ Voices: Representations of Black Womanhood in Street Literature and Hip-Hop Music AUTHOR: Marquita R. Smith, B.A. (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey), M.A. (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mary O’Connor NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 196 iii Ph.D. Thesis – M. Smith McMaster University – English & Cultural Studies ABSTRACT This dissertation draws upon literary and cultural studies, hip-hop studies, and hip-hop feminism to explore Black women’s critical engagement with the boundaries of Black womanhood in the cultural productions of street literature and hip-hop music. The term “troublesome” motivates my analysis as I argue that the works of writers Teri Woods and Sister Souljah and of rapper Lil’ Kim create narratives that alternately highlight, reproduce, and challenge racist, classist, and sexist discourse on Black womanhood. Such narratives reveal hip-hop to be a site for critical reflection on Black womanhood and offer context-specific examples of the intersectionality of hip-hop generation women’s experiences. This project also incorporates ethnographic methods to document and validate the experiential knowledge of street literature readers. -

Spring Courses

VOL. 4 NO. 2 THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY DECEMBER, 1992 Spring Courses Family Weekend: t>y The Watchdog gence Of CivifrttUlont A The Extravaganza Cross-Cultural Examina by Perspective Staff Directorof Multicultural Stu What ORdergradaate tion MW10 dent Affairs Janet Moore, and xtursesdealingwith Africans On Saturday, October 31 Director of Security Ron mdor African Americansate 140 J«S(H^>Race,Health, the BSU sponsored its annual Mullen. )cing taught next semester? and Medicine in the United Family Weekend Program/ The event was organized One would think that since States. T1-3 Reception. The standing room by BSU Community Rela bis is such adivetse Univer only event was held in the tions chair and included per sity. a look at the coarse 30ft.363(H){W) Contem Garrett Room, and over 100 formances by the JHU Gos sehedulewouldrevealaveri- porary African l iterature students,family members, and pel Choir, Crista Johnson, ahle plethora of courses ThF 12-1:30 administrators attended. Alpha Kappa Alpha, Alpha iboutBlacks.Not “This was the highest turn Phi Alpha, and Kappa Alpha I submit for your chagrin 190:341(8) Topics in out I’ve seen since I’ve been Psi. During the program ind information thcpinkyfut AmeHcan Political here,’’said senior Carlos Margo Butler was recognized ri undergraduate courses Thought W1-3 Greenlee. for the time and effort she put which the University is of Attending University offi into painting the beautiful fering on Africans and those 190.38 7 (S)AfrieanPolitics cials included University Pro murals which adorn the walls af African ancestry next se Through Fiction T 12-2 vost Joseph Cooper, Dean of ofthe BSU room. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

Fresh Connect Marketing Plan 2020

Fresh Connect Marketing Plan 2020 Operational Budget: Individual Paid Ads Fresh Connect Week Flier Facebook: A budget of $5.00 per day for 2 weeks (Week: Start Nov. 22nd and Week Nov. 29) - $70.00 Instagram: A budget of $5.00 per day for 30 days (Week: Start Nov. 11) - $150.00 _________________________________________________________ Smaller Ad Placements (Fundraising/Spons placement content) Facebook: A budget of $5.00 per day for 5 days (2 Posts in total) - $50.00 Instagram: A Budget of $5.00 per day for 7 days (2 Posts in total) - $70.00 _________________________________________________________ Graphic Designer: Logo and additional expenses for fliers - $220.00 Physical Posters (Digital Printing Center) 30 Posters (8x11 or 11x17) - Waiting on the center to reach out Total: $560.00 Platform Daily Price Duration Total Days Posts Total Week Flier Facebook $5 Nov22 - 14 $70 Dec 5 Instagram $5 Nov11 - 30 $150 Dec 10 Smaller Ad Facebook $5 5 2 $50 Placements Instagram $5 7 2 $70 Unit Price Amount Total Logo $100 1 $100 Graphic Designer Flyer $30 3 $120 Physical Posters 30 In Total: $560 EVENT / CONTENT Calendar: FOR THE MONTH OF NOVEMBER Funding proposal documentation must include (but is not limited to) the following: Team Objectives ● Objective 1: Increase the amount of social interaction we get on social media by utilizing ads and interactions. We hope to raise Facebook's followers up to 700 from 243 and Instagram from 176 to 500 by December 7th. ● Objective 2: To market as many artists as we can through proposals, video interactions and articles. We will showcase each featured artist twice a week on Facebook and Instagram closer to the programming(2-3 weeks before December 7th). -

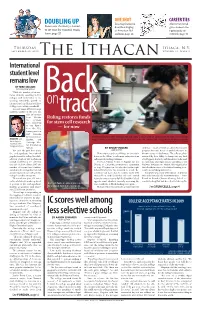

The Ithacan 2010-09-30

ONE SHOT CAREER TIES DOUBLING UP Los Angeles intern Alumni weekend Sisters use chemistry on court describes singing gives students the to set tone for women’s tennis at American Idol opportunity to team, page 23 audition, page 13 network, page 10 Thursday Ithaca, N.Y. September 30, 2010 The Ithacan Volume 78, Issue 6 International student level remains low BY MIKE MCCABE CONTRIBUTING WRITER While the number of interna- tional students enrolling in U.S. colleges and universities is in- Back creasing nationwide, growth in international enrollment at Ithaca on College is at a relative standstill. In total, about 586,000 foreign students studied in the U.S. last year, an increase track from 568,000 the previous Ruling restores funds year, according for stem cell research to visa figures from the U.S. — for now I m m i g r at i o n and Customs Enforcement’s Cornell University staffer Christian Abratte takes a closer look at animal cells through a microscope MAU G IRE said Student and Sept. 21 in the Cornell Stem Cell Lab. Research at the lab could be affected by fluctuating federal funds. the college is CLAUDIA PIETRZAK/THE ITHacaN reaching out to Exchange Visi- foreign countries. tor Information System. BY KELSEY FOWLER embryos — most of which are given for research But over the past four years, STAFF WRITER purposes from the donor or would otherwise be the undergraduate international University researchers still face an uncertain thrown out as medical waste. The cells are char- population at the college has shift- future as the debate over human embryotic stem acterized by their ability to change into any kind ed from a high of 156 students in cell research funding continues. -

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 COOLIDGE AVE

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 COOLIDGE AVE. U.S. POSTAGE LOS ANGELES, CA 90066 PAID Culver City, CA Permit No. 69 First Class Mail Dated Material ORDER FORM Please enter my subscription to FOLK DANCE SCENE for one year, beginning with the next published issue. Subscription rate: $15.00/year (U.S. First Class), $18.00/year in U.S. currency (Foreign) Published monthly except for June/July and December/January issues. NAME _________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________ PHONE (_____)_____–________ CITY _________________________________________ STATE __________________ E-MAIL _________________________________________ ZIP __________–________ Please mail subscription orders to the Subscription Office: 2010 Parnell Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90025 (Allow 6-8 weeks for subscription to go into effect if order is mailed after the 10th of the month.) Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 38, No. 2 March 2002 Folk Dance Scene Committee Club Directory Coordinators Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Beginner’s Classes Calendar Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Club Time Contact Location Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 CABRILLO INT'L FOLK Tue 7:00-8:00 (858) 459-1336 Georgina SAN DIEGO, Balboa Park Club Contributing Editor Richard Duree [email protected] (714) 641-7450 DANCERS Thu 7:30-8:30 (619) 445-4907