Differential Effects of a Cognitive Interference Task After Encoding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-Term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms Ahmed Mohammed Saleh Alduais (Corresponding author) Department of Linguistics, Social Sciences Institute Ankara University, 06100 Sıhhiye, Ankara, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Yasir Saad Almukhaizeem Department of Linguistics and Translation, College of Languages and Translation King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Received: 29/05/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Accepted: 18/08/2015 The research is financed by Research Centre in the College of Languages and Translation Studies and the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Abstract Purpose: To see if there is a correlation between interference and short-term memory recall and to examine interference as a factor affecting memory recalling of Arabic and abstract words through free, cued, and serial recall tasks. Method: Four groups of undergraduates in King Saud University, Saudi Arabia participated in this study. The first group consisted of 9 undergraduates who were trained to perform three types of recall for 20 Arabic abstract and concrete words. The second, third and fourth groups consisted of 27 undergraduates where each group was trained only to perform one recall type: free recall, cued recall and serial recall respectively. -

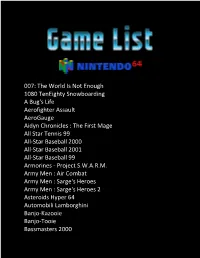

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

THE ART of Puzzle Game Design

THE ART OF Puzzle Design Scott Kim & Alexey Pajitnov with Bob Bates, Gary Rosenzweig, Michael Wyman March 8, 2000 Game Developers Conference These are presentation slides from an all-day tutorial given at the 2000 Game Developers Conference in San Jose, California (www.gdconf.com). After the conference, the slides will be available at www.scottkim.com. Puzzles Part of many games. Adventure, education, action, web But how do you create them? Puzzles are an important part of many computer games. Cartridge-based action puzzle gamse, CD-ROM puzzle anthologies, adventure game, and educational game all need good puzzles. Good News / Bad News Mental challenge Marketable? Nonviolent Dramatic? Easy to program Hard to invent? Growing market Small market? The good news is that puzzles appeal widely to both males and females of all ages. Although the market is small, it is rapidly expanding, as computers become a mass market commodity and the internet shifts computer games toward familiar, quick, easy-to-learn games. Outline MORNING AFTERNOON What is a puzzle? Guest Speakers Examples Exercise Case studies Question & Design process Answer We’ll start by discussing genres of puzzle games. We’ll study some classic puzzle games, and current projects. We’ll cover the eight steps of the puzzle design process. We’ll hear from guest speakers. Finally we’ll do hands-on projects, with time for question and answer. What is a Puzzle? Five ways of defining puzzle games First, let’s map out the basic genres of puzzle games. Scott Kim 1. Definition of “Puzzle” A puzzle is fun and has a right answer. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Research Article Arthur P. Shimamura

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article MEMORY AND COGNITIVE ABILITIES IN UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS: Evidence for Successful Aging Arthur P. Shimamura,' Jane M. Berry,^ Jennifer A. Mangels,' Cheryl L. Rusting,^ and Paul J. Jurica* 'University of California, Berkeley, 'University of Richmond, and ^University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Abstract—Professors from the University of California at Schaie, 1990, 1994) That is, professors may develop efficient Berkeley were administered a 90-min test battery of cognitive use of cognitive abiliues or strategies that may prevent or mit- performance that included measures of reaction time, paired- igate aging effects associate learning, working memory, and prose recall Age ef- University professors between the ages of 30 and 71 years fects among the professors were observed on tests of reaction were administered a battery of memory and cognitive tests The time, paired-associate memory, and some aspects of working particular tests were chosen because they were known to be memory Age effects were not observed on measures of proac- sensitive markers of age-related changes (e g , choice reaction tive interference and prose recall, though age-related declines time, free recall) or known to be associated with circumscnbed are generally observed m standard groups of elderly individu- neurological dysfunction (e g , medial temporal or frontal lobe als The findings suggest that age-related decrements in certain impairment) Several hypotheses were entertained with regard cognitive functions may be mitigated in intelligent, -

Examining the Relationship Between Free Recall and Immediate Serial Recall: the Serial Nature of Recall and the Effect of Test Expectancy

Memory & Cognition 2008, 36 (1), 20-34 doi: 10.3758/MC.36.1.20 Examining the relationship between free recall and immediate serial recall: The serial nature of recall and the effect of test expectancy PARVEEN BHATARAH London Metropolitan University, London, England GEOFF WARD University of Essex, Colchester, England AND LYDIA TAN City University London, London, England In two experiments, we examined the relationship between free recall and immediate serial recall (ISR), using a within-subjects (Experiment 1) and a between-subjects (Experiment 2) design. In both experiments, partici- pants read aloud lists of eight words and were precued or postcued to respond using free recall or ISR. The serial position curves were U-shaped for free recall and showed extended primacy effects with little or no recency for ISR, and there was little or no difference between recall for the precued and the postcued conditions. Critically, analyses of the output order showed that although the participants started their recall from different list positions in the two tasks, the degree to which subsequent recall was serial in a forward order was strikingly similar. We argue that recalling in a serial forward order is a general characteristic of memory and that performance on ISR and free recall is underpinned by common memory mechanisms. Free recall and immediate serial recall (ISR) are two correct order on 50% of the trials. The classic explanation immediate memory tasks in which participants are pre- for the memory span is that it reflects the capacity limita- sented with lists of words to study, one word at a time, tions of the STS, in terms of either the number of chunks and then, after the presentation of the last word in a list, of items that can be recalled (e.g., Miller, 1956) or the they must try to recall as many of the items as they can. -

Conference Overview

The 17th IGSC Proudly Presents Keynote Speaker: Henk Rogers, Entrepreneur “My Story and Vision for the Future” Henk B. Rogers is a Dutch-born entrepreneur and clean energy visionary, who has dedicated the past decade of his career to the research, development, advocacy and implementation of renewable energy sources in his adopted home of Hawaii. Rogers studied computer science at the University of Hawaii and spent his early career in Japan as a video game developer and publisher, gaining distinction for producing the country’s first Role-Playing Game, The Black Onyx. Rogers went on to revolutionize the video game industry by securing the rights for the blockbuster, Tetris. Today, Rogers serves as chairman of Blue Planet Software, the sole agent for the Tetris franchise; founder of Blue Planet Foundation, the state’s leading nonprofit clean energy advocate; founder of Blue Startups, Hawaii’s first venture accelerator for local technology entrepreneurs; founder of Blue Planet Research, which is working on off-grid solutions and exploring the hydrogen economy; and founder of the International MoonBase Alliance. In 2014, he founded Blue Planet Energy Systems to advance his mission of ending the use of carbon-based fuel worldwide, with Hawaii leading the charge. 17th East-West Center International Graduate Student Conference on the Asia-Pacific Region Imin International Conference Center Honolulu, Hawai‘i February 15 – 17, 2018 Program Cover design by Jonah Preising The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. -

Intrusions in Episodic Recall: Age Differences in Editing of Overt Responses

Journal of Gerontology: PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES Copyright 2005 by The Gerontological Society of America 2005, Vol. 60B, No. 2, P92–P97 Intrusions in Episodic Recall: Age Differences in Editing of Overt Responses Michael J. Kahana,1 Emily D. Dolan,1 Colin L. Sauder,1 and Arthur Wingfield2 1Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. 2Volen Center for Complex Systems, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts. Two experiments compared episodic word-list recall of young and older adults. In Experiment 1, using standard free-recall procedures, older adults recalled significantly fewer correct items and made significantly more intrusions (recall of items that had not appeared on the target list) than younger adults. In Experiment 2, we introduced a new method, called externalized free recall, in which participants were asked to recall any items that came to mind during the recall period but to indicate with an immediate key press those items they could identify as intrusions. Both age groups generated a large number of intrusions, but older adults were significantly less likely than young adults to identify these as nonlist items. Results suggest that an editing deficit may be a contributor to age differences in episodic recall and that externalized free recall may be a useful tool for testing computationally explicit models of episodic recall. O UNDERSTAND the mechanisms underlying episodic process that limits responses to those items that were in the T memory, we must understand both correct responses and target list. SAM thus embraces the classic generate–recognize memory errors. In word-list recall tasks, errors reflect both view that participants do in fact think of many items that were omissions from a to-be-recalled memory set plus intrusions in not on the target list, but that they reject those responses prior to the form of erroneous recall of items that had not appeared in the producing them for overt recall (Anderson & Bower, 1972; target list. -

Memory Search

Memory Search Michael J. Kahana Department of Psychology University of Pennsylvania Draft: Do not quote Abstract Much has been learned about the dynamics of memory search in the last two decades, primarily through the lens of the free recall task. Here I review the major empirical findings obtained using this memory-search paradigm. I also discuss how these findings have been used to advance theories of memory search. Specific topics covered include serial-position effects, recall dynam- ics and organizational processes, false recall, repetition and spacing effects, inter-response times, and individual differences. At our dinner table each evening my wife and I ask our children to tell us what hap- pened to them at school that day; our older ones sometimes ask us to tell them stories from our day at work. Answering these questions requires that we each search our memories for the day's events, and evaluate each memory's interest value for the dinner table conversa- tion. Our search must target those memories that belong to a particular context, usually defined by the time and place in which the event occurred. In the psychological laboratory, this task is referred to as free recall, and is studied by first having subjects experience a series of items (the study list), Then, either immediately or after some delay, subjects attempt to recall as many items as they can remember irrespective of the items' order of presentation. Unlike other memory tasks, free recall does not provide a specific retrieval cue for each target item. Typically, items are common words presented one at a time on a computer monitor.