The Development of Settlement Patterns in Hay River, Northwest Territories, 1892-1971

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Economic Assessment Toolbox (SEAT) Report for the Period 1 January to 31 December 2013 B SEAT REPORT 2013

Snap Lake Mine Socio-Economic Assessment Toolbox (SEAT) Report for the period 1 January to 31 December 2013 B SEAT REPORT 2013 CONTENTS Foreword . 1 Training in 2013 . 37 Executive Summary . 2 Opportunities for Students . 38 Introduction . 4 Scholarships and Summer Students . 38 Background . 4 NWT Post-secondary Scholarships Report Structure . 4 Awarded in 2013 . 39 Acknowledgements . 4 Shelby Skinner Puts Her Learning to Work at Snap Lake . 40 1 THE SEAT PROCESS 5 Keelan Mooney: De Beers Sponsorship . 41 Health and Wellness . 42 SEAT Objectives . 6 Fitness Centre . 42 Approach . 7 Fit for Purpose . 42 Stakeholder Engagement and the SEAT Process . 7 The Power of the Spoon . 43 Community Conversations . 8 Snap Lake Mine Family Visit . 44 NWT Business Policy . 45 2 SNAP LAKE MINE AND ITS COMMUNITIES OF INTEREST 11 Partnering with Northern Business . 45 Profile of Snap Lake Mine . 10 Partners in Business . 46 Employment . 12 Corporate Social Investment . 47 Mine Operations . 12 A Million Good Reasons to Invest . 47 Capital Investment . 12 Committed to Addressing the Social Life of Mine . 12 and Economic Impacts of the Mine . 48 Communities near Snap Lake . 13 Charity Golf Classic . 49 Tłįcho Communities . 14 Stanton Diamond Fundraiser . 49 Yellowknives Dene First Nations Communities . 22 Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation Community . 24 4 SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 51 North Slave Métis Alliance . 26 Plan for Success . 52 Yellowknife . 26 A Million Good Reasons to Invest . 47 3 SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND INVESTMENT 29 APPENDIX 1 - 2013 EMPLOYMENT DATA 57 Employment . 30 Employment by the Numbers . 30 APPENDIX 2 - GLOSSARY AND CONTACT DETAILS 69 Women in Mining . -

Last Putt of 2020

No changes planned after ENR shooting Fort Simpson man wants more firearms training for wildlife officers 1257+:(677(55,725,(6 Two-school educator recognized Volume 75 Issue 19 MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2020 $.95 (plus GST) Homes razed by fires in Inuvik Premier creates 150- job Covid secretariat 'The Dope Experience' hits Inuvik Last putt of 2020 Eric Bowling/NNSL photo Kevin McLeod lines up a perfect putt. Roads End Golf Club in Inuvik closed out its summer with a bang, hosting a mixed tournament that drew 15 teams to com- pete for the final glory of the year on Aug. 27 to 28. See more photos on page 15. Publication mail Contract #40012157 "I thank all of you for adapting to keep each other safe." 7 71605 00200 2 – Chief public health officer Kami Kandola points to the success of the school year this far, page 6. 2 NEWS/NORTH NWT, Monday, September 7, 2020 news Five MLAs stayed home from caucus retreat in Fort Smith Many cited personal reasons for not attending by Blair McBride Jackson Lafferty, MLA for Monfwi, con- Northern News Services firmed to NNSL Media that he wasn't present NWT for the event for personal reasons. Members of the legislative assembly held Rocky Simpson, MLA for Hay River their caucus retreat in Fort Smith from Aug. South, was the fifth member who missed the 28 to 31, but five MLAs didn't attend. gathering of legislators as he was travelling Katrina Nokleby, MLA for Great Slave, outside of the territory, said a representative announced in a Facebook post on Aug. -

Great Slave 4 5111 4904 (5 5012 5102 4407 4914

4910 4909 4920 5010 4816 4903 4922 4601 4909 4912 4909 4919 4609 4702 4902 4904 4922 4919 5003 4909 4904 4922 5009 . 4911 4919 e 5013 4922 4701 v ve 4917 A A 4908 4903 4701 5010 4910 4915 5009 w 9 4922 5010 a 4 4701 5016 r 4912 4922 4 4301 4919 4709 6 D 4701 5013 5018 S l 4907 4919 4922 5003 4916 5015 5020 t. o 4807 o 4303 4909 4909 4921 4306 4807 5010 h 5009 5017 c 4810 4801 5012 5024 4305 4807 4913 4308 S 4908 4918 5009 5019 5004 5014 5024 4807 4920 4910 4915 5009 4501 4807 5016 5021 4310 4307 4807 4902 . 4919 5003 5006 4807 4912 5011 4 5023 ve 4807 4907 5006 5018 5102 5518 4807 4919 5013 7 A 4914 4902 5003 S 1 4309 ) 4909 4919 t 5 5104 4312 5518 4807 . 5012 5015 . 5003 5020 5106 5520 5519 ve 4911 5023 5103 4311 4914 4807 A 4910 5012 5022 5108 4314 9 5305 4807 4908 4915 4918 5009 4313 (4 5014 5023 5105 5110 4316 5527 4915 ive 5023 5107 r 4910 4315 D 4917 5016 5109 5112 4503 5522 l 4912 5004 5023 5525 a 5102 44 St 5210 i 4907 5018 511FALL4 2020. 5521 r 4909 4914 4919 5010 5020 5111 o 5016 m 5104 e 4909 5113 4401 M 4916 5001 5020 5103 5116 5018 5108 s 5001 5020 5524 n 4908 5019 5115 a 4913 5105 Electoral District of r 4913 5117 4403 te 5102 5004 e 5105 5110 4601 4402 4814 4910 5 ) 5021 5119 V 4912 2 4917 . -

Interview Summary

Interview Summary Interviewee: Ronnie Semansha Date: November 4, 2009 Location: Chateh Administration Office Interviewers: Kathrin Janssen, Adena Dinn “This [BC] is our traditional lands” -Ronnie Semansha Hunting and Trapping Ronnie hunts for moose in British Columbia (BC) near Kotcho Lake along the winter access road that spans from Rainbow Lake to Fort Nelson. He once shot a moose adjacent to Cabin Lake. He also uses the Sierra Yoyo Desan road and the winter access road that loops around Kotcho Lake for hunting. He takes this route once a week beginning on Friday afternoons when he is finished work. Ronnie also hunts in the area near Kwokullie Lake; he travels there via the winter access on the 31st baseline. Ronnie strictly hunts for moose in BC, and noted that there are hardly any caribou left. He explained that there used to be lots of caribou in BC but there has been a drop in recent times. Fishing Ronnie noted that there are pickerel in Kotcho Lake and explained that there are all different kinds of fish out there [BC]. Travel Routes Ronnie travels to BC using the winter access roads. He noted that there were two roads that he generally used, one from Rainbow Lake to Fort Nelson and one that cuts North to the Zama area (along the 31st baseline). When he does go out, other community members will often accompany him and everyone chips in a little for gas and supplies. However, he generally goes out for just one day and does not require supplies beyond fuel. Transcript 13 If he cannot travel to a certain area via the winter roads then Ronnie will often use a skidoo and the cutlines to access those areas. -

Official Voting Results 2007

2007 Election of the Sixteenth Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories Official Voting Results Published by the Chief Electoral Officer Office of the Chief Electoral Officer November 23, 2007 The Honourable Paul Delorey Speaker Legislative Assembly of the NWT P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Dear Mr. Speaker, Official Voting Results Pursuant to section 265 of the Elections and Plebiscites Act, it is my pleasure to provide you with the official voting results for the general election held on October 1, 2007 for the 16th Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. This report provides poll-by-poll results for the 16 electoral districts in which an election was held and details the acclamations of candidates in three electoral districts. Sincerely, S. Arberry Chief Electoral Officer Mailing Address: #7, 4915 - 48th Street, Yellowknife, NT X1A 3S4 Phone: (867) 920-6999 or 1-800-661-0796 • Fax: (867) 873-0366 or 1-800-661-0872 e-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.electionsnwt.ca Table of Contents Official Voting Results Summary of Votes Cast by Electoral District .................................................................................................................. 1 Poll-by-Poll Results Deh Cho ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Frame Lake .................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

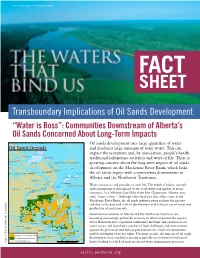

Transboundary Implications of Oil Sands Development “Water Is Boss”: Communities Downstream of Alberta’S Oil Sands Concerned About Long-Term Impacts

Photo: David Dodge, The Pembina Institute FACT SHEET Transboundary Implications of Oil Sands Development “Water is Boss”: Communities Downstream of Alberta’s Oil Sands Concerned About Long-Term Impacts Yellowknife (! Lutselk'e (! Oil sands development uses large quantities of water Oil Sands Deposit and produces large amounts of toxic waste. This can Great Slave Lake impact the ecosystem and, by association, people’s health, Fort Providence (! Fort Resolution (! traditional subsistence activities and ways of life. There is ie River ackenz M Hay River S la Northwest Territories (! v growing concern about the long-term impact of oil sands e R iv e r development on the Mackenzie River Basin, which links Fort Smith (! Fond-du-Lac (! the oil sands region with communities downstream in Lake Athabasca Alberta and the Northwest Territories. er Alberta iv R ce Fort Chipewyan a (! Pe Saskatchewan Water sustains us and provides us with life. The health of plants, animals Lake Claire High Level Fox Lake Rainbow Lake (! (! and communities is determined by the availability and quality of water (! Fort Vermilion (! La Crête (! resources. As a Mikisew Cree Elder from Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, once said, “water is boss.” Although other land uses also affect water in the Mackenzie River Basin, the oil sands industry poses perhaps the greatest risk due to the pace and scale of development and its heavy use of water and Manning Fort McMurray La Loche (! ! (! r ( e production of contaminants. iv R a c s a Buffalo Narrows Peace River b (! a Downstream residents in Alberta and the Northwest Territories are (! h Wabasca t Fairview (! A (! becoming increasingly politically active in an effort to protect the region’s High Prairie water. -

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories DFO L b ary / MPO Bibliotheque 1 1 11 0801752111 1 1111 1 1 D.B. Stewart' Central and Arctic Region Department of Fisheries and Oceans Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 'Arctic Biological Consultants Box 68, St. Norbert Postal Station 95 Turnbull Drive Winnipeg, MB, R3V 1L5. 1999 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2493 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901-1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426-1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports. -

South Saskatchewan River Legal and Inter-Jurisdictional Institutional Water Map

South Saskatchewan River Legal and Inter-jurisdictional Institutional Water Map. Derived by L. Patiño and D. Gauthier, mainly from Hurlbert, Margot. 2006. Water Law in the South Saskatchewan River Basin. IACC Project working paper No. 27. March, 2007. May, 2007. Brief Explanation of the South Saskatchewan River Basin Legal and Inter- jurisdictional Institutional Water Map Charts. This document provides a brief explanation of the legal and inter-jurisdictional water institutional map charts in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB). This work has been derived from Hurlbert, Margot. 2006. Water Law in the South Saskatchewan River Basin. IACC Project working paper No. 27. The main purpose of the charts is to provide a visual representation of the relevant water legal and inter-jurisdictional institutions involved in the management, decision-making process and monitoring/enforcement of water resources (quality and quantity) in Saskatchewan and Alberta, at the federal, inter-jurisdictional, provincial and local levels. The charts do not intend to provide an extensive representation of all water legal and/or inter-jurisdictional institutions, nor a comprehensive list of roles and responsibilities. Rather to serve as visual tools that allow the observer to obtain a relatively prompt working understanding of the current water legal and inter-jurisdictional institutional structure existing in each province. Following are the main components of the charts: 1. The charts provide information regarding water quantity and water quality. To facilitate a prompt reading between water quality and water quantity the charts have been colour coded. Water quantity has been depicted in red (i.e., text, boxes, link lines and arrows), and contains only one subdivision, water allocation. -

Hay River Region

The Hay Water RiverMonitoring Activities in the Hay River Region Kátåo’dehé at Enterprise Kátåo’dehé is the South Slavey Dene name for the Hay River. In Chipewyan, the Hay River is Hátå’oresche. In Cree, it is Maskosï-Sïpiy. The Hay River is a culturally significant river for Northerners and an integral part of the Mackenzie River Basin. Given its importance, there are several monitoring initiatives in the region designed to better understand the river and to detect changes. The information collected through these programs can also help to address questions that people may have. While amounts vary from year to year, the volume of water in the Hay River has remained relatively stable since monitoring began in 1963. Only a slight increasing trend in winter flow was revealed. Some changes in water quality were also found, such as increasing trends in phosphorus and decreasing trends in calcium, magnesium and sulphate. This means that the levels of these substances have changed since sampling began in 1988. Further work is needed to understand the ecological significance of these trends. Overall, the water quality and quantity of the Hay River is good. Continued monitoring activities will increase our knowledge of this important river and identify change. It is important that all water partners work closely together on any monitoring initiatives. 1 Water Monitoring Activities in the Hay River Region For information regarding reproduction rights, please contact Public Works and Government Services Canada at: (613) 996-6886 or at: [email protected] www.aandc.gc.ca 1-800-567-9604 TTY only 1-866-553-0554 QS-Y389-000-EE-A1 Catalogue: R3-206/2014E ISBN: 978-1-100-233343-7 © Her Majesty the Queen in right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, 2014 This Publication is also available in French under the title: La Rivière Hay : activités de surveillance de l’eau dans la région de la rivière Hay. -

Report on the Peace River and Tributaries in 1891, by Wm

I PART VII. PEACE RIVER AND TRIBUTARIES f 1 Q ] i[i ^ ;<: Jj« ;;c >': Jj< V 0E (Purchased pr da ^ovu 'Pierce (jpttectioTL, at Ouun/s University qkwjl 4 PART VII. REPORT ON THE PEACE RIVER AND TRIBUTARIES IN 1891, BY WM. OGILVIE. Ottawa, Tth April, 1892. To the Honourable The Minister of the Interior Sir,—I respectfully submit the following report of my operations for the season of 1891. On the 5th of June of that year instructions were issued to me from the Surveyor- General's Office directing me to make a thorough exploration of the region drained by the Peace River and its tributaries, between the boundary of British Columbia and the Rocky Mountains, and to collect any information that may be of value relating to that region. The nature and extent of my work was, of necessity, left largely to myself, as also was the method of my surveys. As it was desirable that I should, if practicable, connect the end of my micrometer survey of the Mackenzie River made in 1888 with that made on the Great Slave River in the same year, which I was then unable to accomplish on account of high water, I took along the necessary instruments, but owing to circum- stances which will be detailed further on I found it impossible to complete this work. Immediately upon intimation that this work was to be intrusted to me I ordered a suitable canoe from the Ontario Canoe Company, Peterborough, after having ascertained that I could obtain it more quickly there than elsewhere. -

Arctic Environmental Strategy Summary of Recent Aquatic Ecosystem Studies Northern Water Resources Studies

Arctic Environmental Strategy Summary of Recent Aquatic Ecosystem Studies Northern Water Resources Studies Arctic Environmental Strategy Summary ofRecent Aquatic Ecosystem Studies August 1995 Northern Affairs Program Edited by J. Chouinard D. Milburn Published under the authority of the Honourable Ronald A. Irwin, P.C., M.P., Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Ottawa, 1995 QS-8507-030-EF-Al Catalogue No. R72-244/1-1995E ISBN 0-662-23939-3 © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada FOREWORD The Arctic Environmental Strategy (AES), announced in April 1991, is a six-year $100 million Green Plan initiative. The overall goal ofthe AES is to preserve and enhance the integrity, health, biodiversity and productivity ofour Arctic ecosystems for the benefit ofpresent and future generations. Four specific programs address some ofthe key environmental challenges: they are waste cleanup, contaminants, water management, and environment and economy integration. The programs are managed by the Northern Affairs Program ofthe Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND); however, there is a strong emphasis on partnerships with northern stakeholders including Native organizations, other federal departments and the territorial governments. The AES Action on Water Program specifically strives to enhance the protection ofnorthern freshwaters through improved knowledge and decision-making. Water Resources managers in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories administer this Program which focuses on freshwater aquatic ecosystems. This report is the first detailed compilation ofstudies.conducted under the AES Action on Water Program. It covers work done from 1991 to 1994. Many studies have been concluded, while others are ongoing. Although data may not be available for all studies, or results are preliminary at this time, this report presents detailed background, objectives and methodology. -

Young Elector Participation in the 2015 Territorial General Election

Young Elector Participation in the 2015 Territorial General Election Nara Dapilos Youth Programs Coordinator Office of the Chief Electoral Officer May 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... Youth Voter Turnout in the Northwest Territories ................................................................................................. 1 Voter Turnout by Electoral District (ED) ...................................................................................................... 1 Young Adult Male vs. Female Voter Turnout ............................................................................................... 2 Voter Turnout by Population Estimate ................................................................................................................ 3 Yellowknife Voter Turnout ................................................................................................................................. 4 Conclusion: Potential Outcomes ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction This research paper is intended to analyze election participation of young adults in the Northwest Territories based on data from the 2015 general election. Figure 1 shows a comparison between the NWT population estimate and the number of registered electors in 2015 by age. Within the 18- to 35-year-old age