Andrew Saint, 'The Marble Arch', the Georgian Group Jounal, Vol. VII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Pears, ‘Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 117–134 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 BUILDING HOWICK HALL, NOrthUMBERLAND, 1779–87 RICHARD PEARS Howick Hall was designed by the architect William owick Hall, Northumberland, is a substantial Newton of Newcastle upon Tyne (1730–98) for Sir Hmansion of the 1780s, the former home of Henry Grey, Bt., to replace a medieval tower-house. the Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845), Prime Newton made several designs for the new house, Minister at the time of the 1832 Reform Act. (Fig. 1) drawing upon recent work in north-east England The house replaced a medieval tower and was by James Paine, before arriving at the final design designed by the Newcastle architect William Newton in collaboration with his client. The new house (1730–98) for the Earl’s bachelor uncle Sir Henry incorporated plasterwork by Joseph Rose & Co. The Grey (1733–1808), who took a keen interest in his earlier designs for the new house are published here nephew’s education and emergence as a politician. for the first time, whilst the detailed accounts kept by It was built 1781 to 1788, remodelled on the north Newton reveal the logistical, artisanal and domestic side to make a new entrance in 1809, but the interior requirements of country house construction in the last was devastated in a fire in 1926. Sir Herbert Baker quarter of the eighteenth century. radically remodelled the surviving structure from Fig. 1. Howick Hall, Northumberland, by William Newton, 1781–89. South front and pavilions. -

Picturesque Architecture 2Nd Term 1956 (B3.6)

Picturesque Architecture 2nd Term 1956 (B3.6) In a number of lectures given during the term Professor Burke has shown how during the 18th century, in both the decorative treatment of interiors and in landscape gardening, the principle of symmetry gradually gave way to asymmetry; and regularity to irregularity. This morning I want to show how architecture itself was affected by this new desire for irregularity. It is quite an important point. How important we can see by throwing our thoughts back briefly for a moment over the architectural past we have traced during the year. The Egyptian temple, the Mesopotamian temple, the Greek temple, the Byzantine church, the Gothic church, the Renaissance church, the Baroque church, the rococo country house and the neo- classical palace were all governed by the principle of symmetry. However irregular the Gothic itself became by virtue of its piecemeal building processes, or however wild the Baroque and the Rococo became in their architectural embellishments, they never failed to balance one side of the building with the other side, about a central axis. Let us turn for a moment to our time. Symmetry is certainly not, as we see in out next slide, an overriding rule of contemporary planning. If a symmetrical plan is chosen by an architect today, it is the result of a deliberate choice, chosen for being most suited for the circumstances, and not, as it was in the past, an accepted architectural presupposition dating back to the very beginnings of architecture itself. Today plans are far more often asymmetrical than symmetrical. -

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19Th C

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19th c. Displaced from their farms by technological developments, the industrial laborers - many of them women and children – suffered miserable living and working conditions. Romanticism: late 18th c. - mid. 19th c. During the Industrial Revolution an intellectual and artistic hostility towards the new industrialization developed. This was known as the Romantic movement. The movement stressed the importance of nature in art and language, in contrast to machines and factories. • Interest in folk culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval era; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote and the mysterious. CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. The English Landscape Garden Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England William Kent. Chiswick House Garden. 1724-9 The architectural set- pieces, each in a Picturesque location, include a Temple of Apollo, a Temple of Flora, a Pantheon, and a Palladian bridge. André Le Nôtre. The gardens of Versailles. 1661-1785 Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH, Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. Gothic Revival Architectural movement most commonly associated with Romanticism. It drew its inspiration from medieval architecture and competed with the Neoclassical revival TURNER, The Chancel and Crossing of Tintern Abbey. 1794. Horace Walpole by Joshua Reynolds, 1756 Horace Walpole (1717-97), English politician, writer, architectural innovator and collector. In 1747 he bought a small villa that he transformed into a pseudo-Gothic showplace called Strawberry Hill; it was the inspiration for the Gothic Revival in English domestic architecture. -

Willersley: an Adam Castle in Derbyshire’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Max Craven, ‘Willersley: an Adam castle in Derbyshire’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXII, 2014, pp. 109–122 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2014 WILLERSLEY: AN ADAM CASTLE IN DERBYSHIRE MAXWELL CRAVEN ichard Arkwright, the cotton pioneer, first came Another aspect was architectural. At first, Rto Derbyshire in , when he set up a cotton Arkwright had been obliged to reside in Wirksworth, spinning mill at Cromford, on a somewhat restricted four miles away and, apart from the leased land on site, over which his operations expanded for a which his mills stood, he did not at first own any decade. His investment repaid the risk handsomely, land at Cromford, although he later built up a and from the s he began to relish his success and landholding piecemeal over the ensuing years. started to adapt to his upwardly mobile situation. Indeed, the manor and much of the land had One aspect of this was dynastic, which saw his only originally been owned by a lead merchant, Adam daughter Susannah marry Charles Hurt of Soresby, from whose childless son it had come to his Wirksworth Hall, a member of an old gentry family two sons-in-law, of whom one was William Milnes of and a partner, with his elder brother Francis, in a Aldercar Hall. He, in turn, bought out the other son- major ironworks nearby at Alderwasley. in-law, a parson, in . It would seem that by Fig. : William Day ( ‒ ) ‘ A View of the mills at Cromford’ , (Derby Museums Trust ) THE GEORGIAN GROUP JOURNAL VOLUME XXII WILLERSLEY : AN ADAM CASTLE IN DERBYSHIRE Milnes had been living in a house on The Rock, a bluff overlooking the Derwent at Cromford, which had previously been the Soresbys’. -

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley On 6 February 1813 a bold and imaginative group of music professionals, thirty in number, established the Philharmonic Society of London. Many had competed directly against each other in the heady commercial environment of late eighteenth-century London – setting up orchestras, promoting concerts, performing and publishing music, selling instruments, teaching. Their avowed aim in the new century, radical enough, was to collaborate rather than compete, creating one select organization with an instrumental focus, self-governing and self- financed, that would put love of music above individual gain. Among their remarkable early rules were these: that low and high sectional positions be of equal rank in their orchestra and shared by rotation, that no Society member be paid for playing at the group’s concerts, that large musical works featuring a single soloist be forbidden at the concerts, and that the Soci- ety’s managers be democratically elected every year. Even the group’s chosen name stressed devotion to a harmonious body, coining an English usage – phil-harmonic – that would later mean simply ‘orchestra’ the world over. At the start it was agreed that the Society’s chief vehicle should be a single series of eight public instrumental concerts of the highest quality, mounted during the London season, February or March to June, each year. By cooperation among their fee-paying members, they hoped to achieve not only exciting performances but, crucially, artistic continuity and a steady momentum for fine music that had been impossible before, notably in the era of the high-profile Professional Concert of 1785-93 and rival Salomon-Haydn Concert of 1791-2, 1794 and Opera Concert of 1795. -

Manchester Group of the Victorian Society Newsletter Christmas 2020

MANCHESTER GROUP OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER CHRISTMAS 2020 WELCOME The views expressed within Welcome to the Christmas edition of the Newsletter. this publication are those of the authors concerned and Under normal circumstances we would be wishing all our members a Merry Christmas, not necessarily those of the but this Christmas promises to be like no other. We can do no more than express the wish Manchester Group of the that you all stay safe. Victorian Society. Our programme of events still remains on hold due to the Coronavirus pandemic and yet © Please note that articles further restrictions imposed in November 2020. We regret any inconvenience caused to published in this newsletter members but it is intended that events will resume when conditions allow. are copyright and may not be reproduced in any form without the consent of the author concerned. CONTENTS 2 PETER FLEETWOD HESKETH A LANCASHIRE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIAN 4 FIELDEN PARK WEST DIDSBURY 8 MANCHESTER BREWERS AND THEIR MANSIONS: 10 REMINISCENCES OF PAT BLOOR 1937-2020 11 NEW BOOKS: ROBERT OWEN AND THE ARCHITECT JOSEPH HANSOM 11 FROM THE LOCAL PRESS 12 HERITAGE, CASH AND COVID-19 13 COMMITTEE MATTERS THE MANCHESTER GROUP OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY | 1 PETER FLEETWOOD-HESKETH, A LANCASHIRE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIAN Richard Fletcher Charles Peter Fleetwood-Hesketh (1905-1985) is mainly remembered today for his book, Murray's Lancashire Architectural Guide, published by John Murray in 1955, and rivalling Pevsner's county guides in the Buildings of England series. Although trained as an architect, he built very little, and devoted his time to architectural journalism and acting as consultant to various organisations including the National Trust, the Georgian Group and the Thirties Society. -

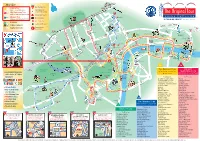

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

How to Find Us Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA

How to find us etc.venues Marble Arch is located on Edgware Road in the heart of the West End. By underground Central line to Marble Arch Station – when you exit the station, turn right on to Oxford Street and then right again on to Edgware Road walking past the Odeon Cinema. etc.venues Garfield House, 86-88 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA Marble Arch is in Garfield House, on the right hand side next to the Tescos. Tel: 020 7793 4200 Fax: 020 7793 4201 By train Email: [email protected] Paddington station is approximately 20 minutes walk. Use the Praed Street exit and turn left on Sat nav: 51.51542, -0.163319 to Praed Street and continue until you walk on to Edgware Road. Turn right onto Edgware Road and continue towards Marble Arch. GLO etc.venues Marble Arch is at the other end of A5 T S Y B Edgware Road on the left. Alternatively bus W B U R O CEST R R O routes 36 or 436 go from outside Paddington A W H N Garfield House on Praed Street and on to Edgware Road and S E T E ST R P 86-88 Edgware Road take approximately 10 minutes to Marble Arch. O RG GE London W2 2EA L G ACE EDG REAT By bus S TESCOTESCO EYMOU WAR etc.venues Marble Arch sits on many bus METROMETRO CU Y ST A41 KELE routes including 7, 10, 73, 98, 137, 390, 6, 23, E M E R R B BERL P E R 94, 159, 30, 94, 113, 159, 274, 2, 16, 36, 74, U P P RD L ACE 82, 148, 414, 436 AN 4 D A520 PL G H T ST Parking R A ST CONNAU M OU CE There is a NCP car park situated within close S EY proximity to Marble Arch - visit www.ncp.co.uk A5 ODEANODEAN MARBLEMARBLE MARBLEMARBLE ARCHARCH for more details. -

Burtons St Leonards Newsletter Autumn 2019

James Burton Decimus Burton 1761-1837 Newsletter Autumn 2019 1800-1881 A GLORIOUS TRIP TO KEW Elizabeth Nathaniels We set off for Kew from St Leonards on a lovely spring day, Tuesday, 30 April. Joining us on the trip was Pat Thomas Allen, one of the authors of the attractive little booklet Travelling with Marianne North, describing the remarkable work of the daughter of a Hastings MP, who re- corded plants and scenery world-wide, and who is duly commemorated in Kew’s gallery named after her. Also with us was David Cruickshank, who plans to create a Marianne North trail in Jamaica, where there are historic links with Kew. During the trip on the coach, our Chairman, Christopher Maxwell-Stewart, and I said a few words about some of the treasures which awaited us. For him, these included a special exhi- bition of the large and intricate glass designs of Dale Chihuly dotted around the grounds, with their glistening brilliant colours and swirly shapes. For me, as ever, my prime interest lay in the work of Decimus Burton whose vast Temperate glass house (1863) (below) – the world’s largest Victorian glasshouse - had been recently restored under the immaculate care of Donald Insall &Associates. The drawing of the octagon may be seen in the archives at Kew. On arrival, free to do as we wished, David Cruickshank, Patrick Glass and I took the outra- geously touristic route by stepping aboard one of the rail-less ‘trains’ which circulate through- out the gardens, every half-hour, allowing passengers to stop off and get on again at will. -

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 140 | MARCH 2002 the College in 1969 with a BA (Honours) Geography

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 140 | MARCH 2002 the College in 1969 with a BA (Honours) Geography. He is now Vice-Chairman of Citigroup, the leading global financial services £4m gift for King’s company. He was formerly Chair- man and Chief Executive Officer of Salomon Brothers, and Vice- Chairman of the New York Stock Exchange. Sir Deryck Maughan said, ‘Va and I are proud to make this donation to the Library at King’s. I came to the College as an undergraduate because of its record of excellence in teaching and research. My education here provided the foundation for my government and business career. ‘We are delighted to be able to largest ever gift from a graduate in the history of the College help the College create an out- standing library, which we hope will provide the same opportuni- ties for independent discovery to future generations of students, whatever their means or back- ground.’ The Library, a distinguished Grade II* listed building, which was formerly the Public Record Office, is a 19th century Gothic masterpiece. It was designed by Sir James Pennethorne to house the nation’s records and incorpo- rates a round reading room simi- lar in style to that in the British Museum. ing’s is celebrating a gener- Above: The The refurbishment of this ous £4 million donation. This Maughan Library gift, the largest ever from K Right: Sir Continued on page 2 a graduate in the history of the Deryck and Lady College, has been made by Sir Maughan Deryck and Lady Maughan. Their donation is for the College’s magnificent new Library in Chancery Lane, which will be named in their honour as the Maughan Library. -

'James and Decimus Burton's Regency New Town, 1827–37'

Elizabeth Nathaniels, ‘James and Decimus Burton’s Regency New Town, 1827–37’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XX, 2012, pp. 151–170 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2012 JAMES AND DECIMUS BURTON’S REGENCY NEW TOWN, ‒ ELIZABETH NATHANIELS During the th anniversary year of the birth of The land, which was part of the -acre Gensing James Burton ( – ) we can re-assess his work, Farm, was put up for sale by the trustees of the late not only as the leading master builder of late Georgian Charles Eversfield following the passing of a private and Regency London but also as the creator of an Act of Parliament which allowed them to grant entire new resort town on the Sussex coast, west of building leases. It included a favourite tourist site – Hastings. The focus of this article will be on Burton’s a valley with stream cutting through the cliff called role as planner of the remarkable townscape and Old Woman’s Tap. (Fig. ) At the bottom stood a landscape of St Leonards-on-Sea. How and why did large flat stone, locally named The Conqueror’s he build it and what role did his son, the acclaimed Table, said to have been where King William I had architect Decimus Burton, play in its creation? dined on the way to the Battle of Hastings. This valley was soon to become the central feature of the ames Burton, the great builder and developer of new town. The Conqueror’s table, however, was to Jlate Georgian London, is best known for his work be unceremoniously removed and replaced by James in the Bedford and Foundling estates, and for the Burton’s grand central St Leonards Hotel. -

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk