Rivers and Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Dayton Duncan Sees the National Parks As the “Declaration of Independence Applied to the Landscape.” Now He and Ken Burns Ha

any years later, as his son faced the Mmountain goats, Dayton Duncan C’71 would remember that distant time when his own parents took him to discover the national parks. He was nine years old then, and nothing in his Iowa upbringing had prepared him for that camping trip to the touchstones of wild America: The lunar grandeur of the Badlands. The bear that stuck its head into their tent in Yellowstone. The muddy murmur of the Green River as it swirled past their sleeping bags at Dinosaur National Monument. Sunrise across Lake Jenny in Grand Dayton Duncan sees the national Teton, an image that would cause parks as the “Declaration his mother’s eyes to grow misty for decades to come … of Independence applied to the landscape.” Now he and Ken Burns have made an epic movie about them. By Samuel Hughes 34 SEPT | OCT 2009 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE THE PHOTOGRAPHPENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE BY SEPTJARED | OCT 2009LEEDS 35 Now it was the summer of 1998, and national parks, and a few weeks later Ken Burns film. For one thing, the Duncan had brought his family to spent three incandescent nights in national parks were a uniquely American Glacier, Montana’s rugged masterpiece Yosemite camping with the legendary invention; for another, their history was of lake and peak and pine. Having spent conservationist John Muir. After the rife with outsized characters and unpre- some blissful days there 13 years before president and the high priest of the dictable plot twists—and issues that still with his then-girlfriend, Dianne, he was Sierras awoke their last morning covered resonate today. -

Nebraska's Territorial Lawmaker, 1854-1867

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Frontier Solons: Nebraska's Territorial Lawmaker, 1854-1867 James B. Potts University of Wisconsin-La Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Potts, James B., "Frontier Solons: Nebraska's Territorial Lawmaker, 1854-1867" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 648. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/648 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FRONTIER SOLONS NEBRASKA'S TERRITORIAL LAWMAKERS, 1854,1867 JAMES B. POTTS In the thirty-seven years since Earl Pomeroy Nevertheless, certain facets of western po maintained that the political history of the mid litical development, including the role of ter nineteenth century American West needed ritorial assemblies, still require "study and "further study and clarification," Howard R. clarification." With few exceptions, territorial Lamar, Lewis Gould, Clark Spence, and other histories have focused upon the activities of fed specialists have produced detailed studies of po erally appointed territorial officials--governors, liticallife in the western territories. Their works secretaries, and, occasionally, judges---and upon have shed light on the everyday workings and the territorial delegates. 2 Considerably less study failures of the American territorial system and has been made of the territorial legislatures, have elucidated the distinctive political and locally elected lawmaking bodies that provide economic conditions that shaped local insti useful perspectives from which to examine fron tutions in Dakota, Wyoming, and other western tier political behavior and attitudes. -

Group Results Sporting Spaniels (English Springer) 19 BB/G1 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza

Tri‐Star KC Saturday, October 10, 2020 Group Results Sporting Spaniels (English Springer) 19 BB/G1 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza. SR89255201 Spaniels (Cocker) Parti‐Color 15 BB/G2 GCHB CH Very Vigie Nobody Is Perfect. SS07199801 Retrievers (Curly‐Coated) 5 BB/G3 GCHS CH Kurly Kreek Copperhead Road DJ DN. SR86611009 Spaniels (Clumber) 5 BB/G4 GCHB CH Cajun & Rainsway's Razzle Dazzle. SR94893803 Hound Greyhounds 10 BB/G1 CH Grandcru Clos Beylesse. HP58406901 Bluetick Coonhounds 7 BB/G2 GCHG CH Evenstar-Wesridge's One Hail Of A Man. HP53416301 American Foxhounds 7 BB/G3 GCH CH Kiarry My Grass Is Blue. HP53814901 Dachshunds (Wirehaired) 28 BB/G4 GCHG CH Colleen's Nancy At Carowynd. HP50213302 Working Samoyeds 15 BB/G1 GCHS CH Vanderbilt 'N Printemp's Lucky Strike. WS54969409 Boxers 56 BB/G2 GCHP2 CH Cinnibon's Bedrock Bombshell. WS51709601 Rottweilers 23 BB/G3 GCHG CH Cammcastle's The One And Only General Of Valor WS55807202 Portuguese Water Dogs 20 BB/G4 GCHP CH Torrid Zone Smoke From A Distant Fire BN RN CGCA CGCU Terrier Welsh Terriers 9 BB/Gs/BIS GCHG CH Brightluck Money Talks. RN29480501 Scottish Terriers 18 BB/G2 GCHP CH Whiskybae Haslemere Habanera. RN29251603 Staffordshire Bull Terriers 5 1/W/BB/BW/G3 Jetstaff's I Won't Back Down. RN34500006 Dandie Dinmont Terriers 9 BB/G4 GCH CH King's Mtn. Henry Higgins. RN31869601 Toy Pekingese 11 BB/G1/RBIS GCHB CH Pequest Wasabi. TS38696002 Shih Tzu 9 1/W/BB/BW/G2 Dan Su N Wenrick Cash Money In Fancy Pants. TS42884202 Pomeranians 35 BB/G3 CH Mountain Crest James Dean. -

October to December 2012 Calendar

October to December 2012 DIVISION OF PUBLIC PROGRAMS EVENTS, EXHIBITIONS, AND PROGRAMS EXHIBITION OPENINGS OCTOBER Fall The huge Black Sunday storm—the LOWER EAST SIDE TENEMENT worst storm of the decade-long Dust MUSEUM, New York, NY Bowl in the southern Plains—just before it engulfed the Church of God Shop Talk in Ulysses, Kansas, April 14, 1935. Long-term. www.tenement.org Daylight turned to total blackness in mid-afternoon. From the October to January 2013 documentary film The Dust Bowl PORT DISCOVERY CHILDREN’S airing November 18 on PBS (check MUSEUM, Baltimore, MD local listings). Courtesy,Historic Adobe Museum. Gods, Myths, and Mortals: www.pbs.org/kenburns/dustbowl Discover Ancient Greece Traveling. Organized by the Children’s Museum of Manhattan. www.cmom.org October 1 to January 6, 2013 STEPPING STONES MUSEUM FOR CHILDREN, Norwalk, CT October 10 to December 7 October 10 to November 30 Native Voices: New England UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, CULVER EDUCATIONAL Tribal Families AMHERST W.E.B. DUBOIS LIBRARY, FOUNDATION, Culver, IN Traveling. Organized by the Children’s Museum of Boston. www.bostonkids.org Amherst, MA Lincoln: The Constitution and Pride and Passion: The African the Civil War October 3 to November 2 Traveling. American Baseball Experience LOURDES COLLEGE, Sylvania, OH Traveling. Organized by the American Library October 10 to November 30 Manifold Greatness: The Association. www.ala.org HOWARD COUNTY LIBRARY, Creation and Afterlife of the October 10 to November 30 Columbia, MD King James Bible CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY Traveling. Organized by the Folger Lincoln: The Constitution and Shakespeare Library and the American Library CHANNEL ISLANDS, Camarillo, CA the Civil War Association. -

New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Corporation

NEW YORK STATE THOROUGHBRED BREEDING AND DEVELOPMENT FUND CORPORATION Report for the Year 2008 NEW YORK STATE THOROUGHBRED BREEDING AND DEVELOPMENT FUND CORPORATION SARATOGA SPA STATE PARK 19 ROOSEVELT DRIVE-SUITE 250 SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY 12866 Since 1973 PHONE (518) 580-0100 FAX (518) 580-0500 WEB SITE http://www.nybreds.com DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR John D. Sabini, Chairman Martin G. Kinsella and Chairman of the NYS Racing & Wagering Board Patrick Hooker, Commissioner NYS Dept. Of Agriculture and Markets COMPTROLLER John A. Tesiero, Jr., Chairman William D. McCabe, Jr. NYS Racing Commission Harry D. Snyder, Commissioner REGISTRAR NYS Racing Commission Joseph G. McMahon, Member Barbara C. Devine Phillip Trowbridge, Member William B. Wilmot, DVM, Member Howard C. Nolan, Jr., Member WEBSITE & ADVERTISING Edward F. Kelly, Member COORDINATOR James Zito June 2009 To: The Honorable David A. Paterson and Members of the New York State Legislature As I present this annual report for 2008 on behalf of the New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Board of Directors, having just been installed as Chairman in the past month, I wish to reflect on the profound loss the New York racing community experienced in October 2008 with the passing of Lorraine Power Tharp, who so ably served the Fund as its Chairwoman. Her dedication to the Fund was consistent with her lifetime of tireless commitment to a variety of civic and professional organizations here in New York. She will long be remembered not only as a role model for women involved in the practice of law but also as a forceful advocate for the humane treatment of all animals. -

Diagnosis of ADHD Is Important

November 2007 Accurate Diagnosis of ADHD is Important Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is C. Some impairment from the symptoms is pre‐ the most common childhood neuro‐behavioral disorder, sent in 2 or more settings (eg, at school, work with 4‐12 percent of all school age children being af‐ or home). fected. Early recognition, assessment and management of D. There must be clear evidence of clinically sig‐ this condition is important, as proper interventions can nificant impairment in social, academic, or positively influence the educational and psychosocial de‐ occupational functioning. velopment of most children with ADHD. Any effective E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during management plan must begin with an accurate and well‐ the course of a pervasive developmental dis‐ established diagnosis. order, schizophrenia, or other psychotic dis‐ Like any other medical condition, the diagnosis of order and are not better accounted for by an‐ ADHD must start with a phase of information collection, other mental disorder (e.g. mood disorder, which then is interpreted in the context of: anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or 1. A framework for diagnostic decision making personality disorder). 2. Clinician’s professional experience and judgment Children who meet diagnostic criteria for the behav‐ 3. Child’s educational and psychosocial development ioral symptoms of ADHD, but who demonstrate no func‐ and tional impairment, do not meet the diagnostic criteria for 4. Family situation ADHD. A framework for diagnostic decision‐making cannot Such information regarding the core symptoms of serve as the sole diagnostic tool but can provide useful ADHD in various settings, the age of onset, duration of guidance for primary care clinicians faced with such di‐ symptoms, and degree of functional impairment should agnostic challenges routinely. -

Jim Levy, Irish Jewish Gunfighter of the Old West

Jim Levy, Irish Jewish Gunfighter of the Old West By William Rabinowitz It’s been a few quite a few years since Chandler, our grandson, was a little boy. His parents would come down with him every winter, free room and board, and happy Grandparents to baby sit. I doubt they actually came to visit much with the geriatrics but it was a free “vacation”. It is not always sun and surf and pool and hot in Boynton Beach, Fl. Sometimes it is actually cold and rainy here. Today was one of those cold and rainy days. Chandler has long since grown up into a typical American young person more interested in “connecting” in Cancun than vegetating in Boynton Beach anymore. I sat down on the sofa, sweatshirt on, house temperature set to “nursing home” hot, a bowl of popcorn, diet coke and turned on the tube. Speed channel surfing is a game I used to play with Chandler. We would sit in front of the T.V. and flip through the channels as fast as our fingers would move. The object was to try and identify the show in the micro second that the image flashed on the screen. Grandma Sheila sat in her sitting room away from the enervating commotion. She was always busy needle- pointing another treasured wall hanging that will need to be framed and sold someday at an estate sale. With my trusty channel changer at my side, I began flipping through the stations, scanning for something that would be of interest as fast as possible. -

Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains Edited by George C

Tri-Services Cultural Resources Research Center USACERL Special Report 97/2 December 1996 U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction Engineering Research Laboratory Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort, with contributions by George C. Frison, Dennis L. Toom, Michael L. Gregg, John Williams, Laura L. Scheiber, George W. Gill, James C. Miller, Julie E. Francis, Robert C. Mainfort, David Schwab, L. Adrien Hannus, Peter Winham, David Walter, David Meyer, Paul R. Picha, and David G. Stanley A Volume in the Central and Northern Plains Archeological Overview Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 47 1996 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 1996 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archeological and bioarcheological resources of the Northern Plains/ edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort; with contributions by George C. Frison [et al.] p. cm. — (Arkansas Archeological Survey research series; no. 47 (USACERL special report; 97/2) “A volume in the Central and Northern Plains archeological overview.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56349-078-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Great Plains—Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America—Anthropometry—Great Plains. 3. Great Plains—Antiquities. I. Frison, George C. II. Mainfort, Robert C. III. Arkansas Archeological Survey. IV. Series. V. Series: USA-CERL special report: N-97/2. E78.G73A74 1996 96-44361 978’.01—dc21 CIP Abstract The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Northwestern Great Plains states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota is reviewed here. -

The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910)

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 5-1995 Quest for Empire: The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910) Jennifer L. Cutsforth '95 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Cutsforth '95, Jennifer L., "Quest for Empire: The United States Versus Germany (1891-1910)" (1995). Honors Projects. 28. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/28 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. ~lAY 12 1991 Quest For Empi re: The Uni ted states Versus Germany (1891 - 1910) Jenn1fer L. Cutsforth Senlor Research Honors Project -- Hlstory May 1995 • Quest for Emp1re: The Un1ted states versus Germany Part I: 1891 - 1900 German battleships threaten American victory at Man'ila! United States refuses to acknowledge German rights in Samoa! Germany menaces the Western Hemispherel United States reneges on agreement to support German stand at Morocco! The age of imperi aIi sm prompted head 1ines I" ke these in both American and German newspapers at the turn of the century, Although little contact took place previously between the two countries, the diplomacy which did exist had been friendly in nature. -

STEVE MEISNER BIO 01/22/2004 Born: April 17, 1961 1966, Began

Steve Meisner Bio, page 1 205 N. Hazel Street, Whitewater, WI 53190-2119 (262) 473-7184 (e-mail) "[email protected]" web page at "www.stevemeisner.com" STEVE MEISNER BIO 01/22/2004 Born: April 17, 1961 1966, Began study of Piano Accordion at age 5 and performing on stage at age with father Verne Meisner. 1967-68, Won 1st place 2 years at Whitewater 4th of July talent contest ages 6 & 7. 1970, Began study of Cornet at age 9 and performing with the Washington Grade School Band. 1973, Began study & performing on Bass Guitar at age 12. 1974, Began study & performing on Button (diatonic) Accordion at age 13 performing with Verne Meisner. 1975, Featured on first recording with Verne Meisner "Autumn Leaves" and won 1st place 2 years at the Chicago & Milwaukee Button Box Competitions at age 14 & 15. 1976, Performing full time at age 15 with the Verne Meisner Orchestra and the New Frontier Dance Group. Began study of Tuba at age 15 performing with the Whitewater High School Band. 1977-78, Performing at age 16 with the Spike Micale Band, and age 17 with the Joey Klass Band. Won 1st place in Solo and band competition and at age 16. Began formal Piano lessons & music theory at age 16 performing on recordings. 1978, Organized and orchestrated the Steve Meisner Band at age 17 performing together for more than 25 years. Regular performances with Verne Meisner. 1985, Married Barbara Lindl May 19th at age 24. 3 Children: Whitney, Lindsey, Austin 1988, Began study of Drums at age 27 performing on stage and recordings. -

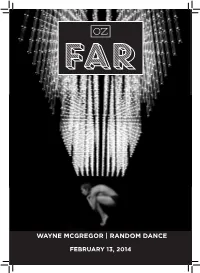

Wayne Mcgregor | Random Dance

WAYNE MCGREGOR | RANDOM DANCE FEBRUARY 13, 2014 OZ SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler A MESSAGE FROM OZ Welcome and thank you for joining us for our first presentation as a new destination for contemporary performing and visual arts in Nashville. By being in the audience, you are not only supporting the visiting artists who have brought their work to Nashville for this rare occasion, you are also supporting the growth of contemporary art in this region. We thank you for your continued support. We are exceptionally lucky and very proud to have with us this evening, one of the worlds’ most inspiring choreographic minds, Wayne McGregor. An artist who emphasizes collaboration and a wide range of perspectives in his creative process, McGregor brings his own brilliant intellect and painterly vision to life in each of his works. In FAR, we witness the mind and body as interconnected forces; distorted and sensual within the same frame. As ten stunning dancers hyperextend and crouch, rapidly moving through light and shadow to a mesmerizing score, the relationship between imagination and movement becomes each viewer’s own interpretation. An acronym for Flesh in the Age of Reason, McGregor’s FAR investigates self-understanding and exemplifies the theme from Roy Porter’s novel by the same name, “that we outlive our mortal existence most enduringly in the ideas we leave behind.” Strap in.