Pwc Solent Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Summary

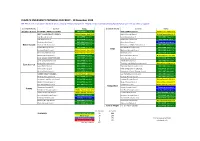

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 10 December 2019 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council Campaign in progress West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge -

Housing Market Partnership for Hart District Council, Rushmoor Borough

Housing Market Partnership for the administrative areas of Hart, Rushmoor and Surrey Heath Terms of Reference (Version 3) Purpose 1. To ensure the Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessments are robust and credible in that they will deliver the core outputs and follow the process checklist as appended 2. To receive and consider reports from commissioned consultants (where appropriate) and feedback from the wider stakeholder group 3. To share and pool information and intelligence, including relevant contextual intelligence and policy information on housing land availability, housing market and financial data 4. To support core members in the analysis and interpretation of the assessment data 5. To consider the implications of the assessments, including signing off the assessment reports, core outputs and agreeing follow up action 6. To agree a process by which the SHLAA findings can be regularly reviewed Membership At its outset, the membership will comprise representatives from the following bodies: Hart District Council Rushmoor Borough Council Surrey Heath Borough Council Berkeley Homes Barton Willmore Mitchell and Partners Gregory Gray Associates Annington Property Ltd Barratt Southern Counties Mitchell and Partners Re-Format Architects Sentinel HA Accent Peerless First Wessex Housing Lovell Partnerships The Rund Partnership Rippon Development Services MGA Planning Rio Homes and Estates These are the organisations that attended either the first meeting, the second meeting, or both. Other key stakeholders1 can join the partnership should they wish to do so by contacting either Hart District Council, Rushmoor Borough Council, or Surrey Heath Borough Council. New members will be invited as necessary to ensure that the housing market area is represented with at least one house builder and preferably with other key stakeholders such as local property and planning agents, Registered Social Landlords and key landowners. -

NE Hants Domestic Abuse Service Directory

Updated February 2020 © North East Hampshire Domestic Abuse Forum Service Directory 2 CONTENTS OF DIRECTORY Page 3 Definition of domestic abuse 5 Safety Planning 6 Commissioned Domestic Abuse Support for those living in Hampshire 8 Local support services for domestic abuse victims 35 Out of area or national services 42 Support for male victims of domestic abuse 44 Support for ethnic minority groups 49 Support for those in LGBT relationships 52 Information for helping deaf or hard of hearing victims 53 Help available for perpetrators 55 Help for those with drug and / or alcohol dependency 58 Support for children and young people affected by domestic abuse 63 Information for those being harassed by e-mail, social network sites or phones Key Domestic Abuse Support Services Contacts Hampshire: Hampshire DA – 0330 0165112 Southampton: PIPPA – 02380 917917 Portsmouth: Stop Domestic Abuse – 02392 065494 Isle of Wight: You Trust – 0800 234 6266 Surrey: Your Sanctuary – 01483 776822 Berkshire: BWA – 0118 9504003 National Helpline Numbers 24 hour National Domestic Violence Helpline: 0808 2000 247 Male Advice Line: 0808 801 0327 National LGBT Domestic Abuse Helpline 0800 999 5428 RESPECT National Helpline for domestic abuse perpetrators 0808 802 4040 © North East Hampshire Domestic Abuse Forum Service Directory 3 DOMESTIC ABUSE DEFINITION The Government definition of domestic violence and abuse is: 'Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. This can encompass, but is not limited to, the following types of abuse: Psychological Physical Sexual Financial Emotional 'Controlling behaviour is: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour. -

Local Government and the Challenges of Service Delivery: the Nigeria Experience

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 15, No.7, 2013) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND THE CHALLENGES OF SERVICE DELIVERY: THE NIGERIA EXPERIENCE Oluwatobi ADEYEMI Department of Local Government Studies, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile- Ife, Nigeria ABSTRACT Nigeria is a Federation of thirty-six States and a Federal Capital Territory located in Abuja. It consists of 774 Local Government Councils. The Constitution recognizes Local Government as the third tier of government whose major responsibility is to ensure affective service delivery to the people, and also enhance sustainable development at the grassroot. The incapacity to generate its own revenue sources leads to its continued dependence on federal allocation, the result of which makes it a stooge rather than a partner in developmental process among the tiers of government in Nigeria leading to little evidence of performance at local level. This study examines the constitutional/functional roles of local government councils in Nigeria in relation to service delivery. It provides a prospect of identifying the factors that has hampered the effectiveness of this institution at grassroots governance in Nigeria. The paper, however provide recommendations in form of solutions to these challenges at the local level. Keywords: Local Government, Services Delivery, Centralization, Decentralization, Fiscal Federalism, Citizen Centered Local Governance, Sustainable Development: 84 INTRODUCTION Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with a population of 140 million (Amakom, 2009), 64 percent of whom live in rural areas. In the pursuit of development at the grassroot, local government was created to provide level of measurable services to rural dwellers. -

Local Government Association of the Northern Territory

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY HOUSE OF REPRESENIATIVE8~STANDJ~cQMMII1TEEON~~ ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER AFFAIRS SUBMISSION TO THE PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO CAPACITY BUILDING IN INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS AUGUST 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. What is this submission about? I 2. What does the Local Government Association stand for and who are its members? 2-3 3. How can capacity be improved? 3-4 4. How can organizations better deliver services? 5-7 5. How can government agencies improve management structures and policy directions? 8-9 2 1. What is this submission about? This submission is about capacity building in Aboriginal Communities in the Northern Territory. It is in response to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs inquiry into capacity building in Indigenous communities. This submission emphasises the role that local government and local governing bodies play in relation to the issue of building capacity in Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory. The reason for this, is that in many instances Councils constitute the only, or most focal, administrative organisation in Indigenous communities and therefore, the view taken here is that questions about capacity building in such communities are very much linked to the role and function of Councils. The Association is very much committed to capacity building for Councils in the Northern Territory indeed, it constitutes an objective of the Association (see next section). The Association is very much a service organisation to local government in the Northern Territory and it would like to expand its range of services so that it can be in a position to offer them at a level similar to that afforded to Councils by their respective associations interstate. -

Community Engagement Toolkit for Planning

Community engagement toolkit for planning August 2017 © State of Queensland. First published by the Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, 1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000, Australia, July 2017. Licence: This work is licensed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Australia Licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute this material in any format, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning) and indicate if any changes have been made. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution: The State of Queensland, Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning on 13 QGOV (13 74 68). Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. -

129 Stoke Road, Gosport, PO12

129 Stoke Road, Gosport, PO12 1SD Investment Summary Gosport is an established coastal town situated on a peninsular to the west of Portsmouth Harbour and the city of Portsmouth. Located 0.5 miles west of Gosport town centre and 6.3 miles south of junction 11 of the M27. Let to the substantial 5A 1 Dun & Bradstreet covenant of Waitrose Limited until 16th July 2025 (5.83 years unexpired). Waitrose have been in occupation since 1973. Passing rent of £220,000 per annum (£9.19) with a fixed uplift to £250,000 (£10.44) in July 2020. Large site area of 0.88 acres. Potential to consider long term redevelopment of the site, subject to necessary planning consent. The adjoining building 133 Stoke Road has permission under permitted development to be converted to 18 one-bedroom residential flats. We are instructed to seek offers in excess of £2,500,000 (Two Million Five Hundred Thousand Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level reflects anet initial yield of 8.27%, a reversionary yield of 9.40% (July 2020) and after purchaser costs of 6.38%. 129 Stoke Road, Gosport, PO12 1SD Petersfield M3 A32 A3057 Eastleigh A3 M27 B3354 Droxford SOUTHAMPTON South Downs AIRPORT National Park M271 B2150 Location A32 A334 SOUTHAMPTON Hedge End Gosport is a coastal town in South Hampshire, situated on a A3(M) Wickham peninsular to the west of Portsmouth Harbour and the city of Waterlooville Portsmouth to which it is linked by the Gosport Ferry. Hythe M27 A326 A27 The town is located approximately 13 miles south west of Fareham A27 Portsmouth, 19 miles south east of Southampton and 6 miles south Havant Titchfield Portchester Cosham east of Fareham. -

List of 100 Priority Places

Priority Places Place Lead Authority Argyll and Bute Argyll and Bute Council Barnsley Sheffield City Region Combined Authority Barrow-in-Furness Cumbria County Council Bassetlaw Nottinghamshire County Council Birmingham West Midlands Combined Authority Blackburn with Darwen Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council Blackpool Blackpool Council Blaenau Gwent Blaenau Gwent Council Bolton Greater Manchester Combined Authority Boston Lincolnshire County Council Bradford West Yorkshire Combined Authority Burnley Lancashire County Council Calderdale West Yorkshire Combined Authority Canterbury Kent County Council Carmarthenshire Carmarthenshire Council Ceredigion Ceredigion Council Conwy Conwy County Borough Council Corby Northamptonshire County Council* Cornwall Cornwall Council County Durham Durham County Council Darlington Tees Valley Combined Authority Denbighshire Denbighshire County Council Derbyshire Dales Derbyshire County Council Doncaster Sheffield City Region Combined Authority Dudley West Midlands Combined Authority Dumfries and Galloway Dumfries and Galloway Council East Ayrshire East Ayrshire Council East Lindsey Lincolnshire County Council East Northamptonshire Northamptonshire County Council* Falkirk Falkirk Council Fenland Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority Gateshead Gateshead Council Glasgow City Glasgow City Council Gravesham Kent County Council Great Yarmouth Norfolk County Council Gwynedd Gwynedd Council Harlow Essex County Council Hartlepool Tees Valley Combined Authority Hastings East Sussex County Council -

Reef Guardian Councils of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment

145°E 150°E 155°E S S ° ° 0 0 1 1 Torres Shire Council Northern Peninsular Area Regional Council Reef Guardian Councils of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment Reef Guardian Councils and Local Government Areas ! Captain Billy Landing Area of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment 424,000 square kilometres %% G BGRBMRMP P LocLaolc Galo Gveorvnemrnemnte nAtr eAarea CaCtachtcmhmenetnt Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council BBAANNAANNAA S SHHIRIREE 66.7.7 BBAARRCCAALLDDININEE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 33.5.5 LEGEND BBLLAACCKKAALLLL T TAAMMBBOO R REEGGIOIONNAALL 00.2.2 Coral Sea BBUUNNDDAABBEERRGG R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.5.5 BBUURRDDEEKKININ S SHHIRIREE 11.2.2 Reef Guardian Council CCAAIRIRNNSS R REEGGIOIONNAALL 00.4.4 Reef Guardian Council area CCAASSSSOOWWAARRYY C COOAASSTT R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.1.1 CENTRAL HIGHLANDS REGIONAL 14.1 extending beyond the Great CENTRAL HIGHLANDS REGIONAL 14.1 CCHHAARRTTEERRSS T TOOWWEERRSS R REEGGIOIONNAALL 1144.9.9 Barrier Reef Catchment boundary CCHHEERRBBOOUURRGG A ABBOORRIGIGININAALL S SHHIRIREE 00.0.0 Local Government Area CCOOOOKK S SHHIRIREE 99.1.1 boundary DDOOUUGGLLAASS S SHHIRIREE 00.6.6 EETTHHEERRIDIDGGEE S SHHIRIREE 00.1.1 Coen ! Great Barrier Reef FFLLININDDEERRSS S SHHIRIREE 00.1.1 ! Port Stewart Marine Park boundary FFRRAASSEERR C COOAASSTT R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.1.1 GGLLAADDSSTTOONNEE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 22.4.4 Indicative Reef boundary GGYYMMPPIEIE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.5.5 HHININCCHHININBBRROOOOKK S SHHIRIREE 00.7.7 Hope Vale Great Barrier Reef Aboriginal Shire Council HHOOPPEE V VAALLEE A ABBOORRIGIGININAALL S SHHIRIREE -

Premier Marinas

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best possible experience on our website - read more or close this message Property About Us Contact Us Marinas Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Gosport Port Solent Southsea Chichester Brighton Eastbourne Onsite and Local Services The Premier Advantage Berthing Options Annual Berthing Winter Berthing Daily Visitor Berthing Dry Stack Dry Berthing Refer a Friend Boatyards Get a Quote Pit Stop Packages Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Port Solent Endeavour Quay Southsea Chichester Eastbourne Brighton Offers from our Tenants Contractor Registration Marine Insurance News & Events Marina News Marina Events Mariners Notices Newsletter Weather & Tides Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Gosport Port Solent Southsea Chichester Brighton Eastbourne My Premier Commercial Property Careers About Us Contact Us Enter search... Premier Marinas Marinas Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Gosport Port Solent Southsea Chichester Brighton Eastbourne Onsite and Local Services The Premier Advantage Berthing Options Annual Berthing Winter Berthing Daily Visitor Berthing Dry Stack Dry Berthing Refer a Friend Boatyards Get a Quote Pit Stop Packages Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Port Solent Endeavour Quay Southsea Chichester Eastbourne Brighton Offers from our Tenants Contractor Registration Marine Insurance News & Events Marina News Marina Events Mariners Notices Newsletter Weather & Tides Falmouth Noss on Dart Swanwick Gosport Port Solent Southsea Chichester Brighton Eastbourne My Premier Give Feedback Daily Visitor Berthing DAILY -

Heart of Hampshire Devolution and the Future of Local

www.pwc.co.uk Final Heart of Hampshire Devolution and the future of local government Confidential November 2016 Future of local government in the Heart of Hampshire Final Contents Important notice .......................................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary...................................................................................................................... 5 Future of local government in the Heart of Hampshire ............................................................................................. 5 Key points from the analysis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Key conclusions and securing a devolution deal ....................................................................................................... 11 Overall conclusion ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Purpose of this report ....................................................................................................................................... 13 1.2. Hampshire and the Isle of Wight .................................................................................................................... -

POLS Course Guide Fall-2021.Pdf

School of Education and Behavioral Sciences Fall 2021 Courses in the Department of Political Science POLS 1101 American Government (Area E, US and Georgia constitutions requirement) Macon, Cochran, Dublin, Warner Robins, Online – various faculty This course is an introduction to the government and political system of the United States, with an emphasis on contemporary American society, including topics such as the U.S. and Georgia constitutions, federalism, civil liberties and civil rights, public opinion, political parties, voting, Congress, the presidency and executive branch, and the courts. POLS 2101 Introduction to Political Science (Area E, required in major and minor) Cochran – TBD, MW 11:00 a.m.–12:15 p.m., CRN 83999 Macon – Dr. John Hall, MW 9:30–10:45 a.m., CRN 84169 This course is a general overview of the political science discipline, introducing basic concepts studied by political scientists such as power, culture, ideology, institutions, and political behavior, as well as orienting students to how political scientists study these questions and the main fields of study within the discipline. POLS 2201 State and Local Government (Area E, required in major, elective in minor) Online – Dr. Julie Lester, CRN 85351 Examines the theory and practice of governing at the state and local level in the United States, including the role of federalism, the varying internal organization of states, the powers of state and local governments, the branches of state government, forms of county/parish and municipal government, and key policy areas that are dealt with by state and local government. POLS 2301 Introduction to Comparative Politics (Area E, required in major, elective in minor) Cochran – Dr.