The Kenya Coast: a Regional Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pollution of Groundwater in the Coastal Kwale District, Kenya

Sustainability of Water Resources under Increasing Uncertainty (Proceedings of the Rabat Symposium S1, April 1997). IAHS Publ. no. 240, 1997. 287 Pollution of groundwater in the coastal Kwale District, Kenya MWAKIO P. TOLE School of Environmental Studies, Moi University, PO Box 3900, Eldoret, Kenya Abstract Groundwater is a "last-resort" source of domestic water supply at the Kenyan coast because of the scarcity of surface water sources. NGOs, the Kenya Government, and international aid organizations have promoted the drilling of shallow boreholes from which water can be pumped using hand- operated pumps that are easy to maintain and repair. The shallow nature and the location of the boreholes in the midst of dense population settlements have made these boreholes susceptible to contamination from septic tanks and pit latrines. Thirteen percent of boreholes studied were contaminated with E. coli, compared to 30% of natural springs and 69% of open wells. Areas underlain by coral limestones show contamination from greater distances (up to 150 m away) compared to areas underlain by sandstones (up to 120 m). Overpumping of the groundwater has also resulted in encroachment of sea water into the coastal aquifers. The 200 ppm CI iso-line appears to be moving increasingly landwards. Sea level rise is expected to compound this problem. There is therefore an urgent need to formulate strategies to protect coastal aquifers from human and sea water contamination. INTRODUCTION The Government of Kenya and several nongovernmental organizations have long recog nized the need to make water more easily accessible to the people in order to improve sanitary conditions, as well as to reduce the time people spend searching for water, so that time can be freed for other productive economic and leisure activities. -

Registered Voters Per Constituency for 2017 General Elections

REGISTERED VOTERS PER CONSTITUENCY FOR 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS COUNTY_ CONST_ NO. OF POLLING COUNTY_NAME CONSTITUENCY_NAME VOTERS CODE CODE STATIONS 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 86,331 136 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 69,307 109 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 126,151 198 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 104,017 165 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 87,326 140 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 107,091 186 002 KWALE 007 MSAMBWENI 68,621 129 002 KWALE 008 LUNGALUNGA 56,948 118 002 KWALE 009 MATUGA 70,366 153 002 KWALE 010 KINANGO 85,106 212 003 KILIFI 011 KILIFI NORTH 101,978 182 003 KILIFI 012 KILIFI SOUTH 84,865 147 003 KILIFI 013 KALOLENI 60,470 123 003 KILIFI 014 RABAI 50,332 93 003 KILIFI 015 GANZE 54,760 132 003 KILIFI 016 MALINDI 87,210 154 003 KILIFI 017 MAGARINI 68,453 157 004 TANA RIVER 018 GARSEN 46,819 113 004 TANA RIVER 019 GALOLE 33,356 93 004 TANA RIVER 020 BURA 38,152 101 005 LAMU 021 LAMU EAST 18,234 45 005 LAMU 022 LAMU WEST 51,542 122 006 TAITA TAVETA 023 TAVETA 34,302 79 006 TAITA TAVETA 024 WUNDANYI 29,911 69 006 TAITA TAVETA 025 MWATATE 39,031 96 006 TAITA TAVETA 026 VOI 52,472 110 007 GARISSA 027 GARISSA TOWNSHIP 54,291 97 007 GARISSA 028 BALAMBALA 20,145 53 007 GARISSA 029 LAGDERA 20,547 46 007 GARISSA 030 DADAAB 25,762 56 007 GARISSA 031 FAFI 19,883 61 007 GARISSA 032 IJARA 22,722 68 008 WAJIR 033 WAJIR NORTH 24,550 76 008 WAJIR 034 WAJIR EAST 26,964 65 008 WAJIR 035 TARBAJ 19,699 50 008 WAJIR 036 WAJIR WEST 27,544 75 008 WAJIR 037 ELDAS 18,676 49 008 WAJIR 038 WAJIR SOUTH 45,469 119 009 MANDERA 039 MANDERA WEST 26,816 58 009 MANDERA 040 BANISSA 18,476 53 009 MANDERA -

County Urban Governance Tools

County Urban Governance Tools This map shows various governance and management approaches counties are using in urban areas Mandera P Turkana Marsabit P West Pokot Wajir ish Elgeyo Samburu Marakwet Busia Trans Nzoia P P Isiolo P tax Bungoma LUFs P Busia Kakamega Baringo Kakamega Uasin P Gishu LUFs Nandi Laikipia Siaya tax P P P Vihiga Meru P Kisumu ga P Nakuru P LUFs LUFs Nyandarua Tharaka Garissa Kericho LUFs Nithi LUFs Nyeri Kirinyaga LUFs Homa Bay Nyamira P Kisii P Muranga Bomet Embu Migori LUFs P Kiambu Nairobi P Narok LUFs P LUFs Kitui Machakos Kisii Tana River Nyamira Makueni Lamu Nairobi P LUFs tax P Kajiado KEY County Budget and Economic Forums (CBEFs) They are meant to serve as the primary institution for ensuring public participation in public finances in order to im- Mom- prove accountability and public participation at the county level. basa Baringo County, Bomet County, Bungoma County, Busia County,Embu County, Elgeyo/ Marakwet County, Homabay County, Kajiado County, Kakamega County, Kericho Count, Kiambu County, Kilifi County, Kirin- yaga County, Kisii County, Kisumu County, Kitui County, Kwale County, Laikipia County, Machakos Coun- LUFs ty, Makueni County, Meru County, Mombasa County, Murang’a County, Nairobi County, Nakuru County, Kilifi Nandi County, Nyandarua County, Nyeri County, Samburu County, Siaya County, TaitaTaveta County, Taita Taveta TharakaNithi County, Trans Nzoia County, Uasin Gishu County Youth Empowerment Programs in urban areas In collaboration with the national government, county governments unveiled -

An Overview of Mental Health Care System in Kilifi, Kenya

Bitta et al. Int J Ment Health Syst (2017) 11:28 DOI 10.1186/s13033-017-0135-5 International Journal of Mental Health Systems RESEARCH Open Access An overview of mental health care system in Kilif, Kenya: results from an initial assessment using the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems Mary A. Bitta1*, Symon M. Kariuki1, Eddie Chengo2 and Charles R. J. C. Newton1,3 Abstract Background: Little is known about the state of mental health systems in Kenya. In 2010, Kenya promulgated a new constitution, which devolved national government and the national health system to 47 counties including Kilif County. There is need to provide evidence from mental health systems research to identify priority areas in Kilif’s men- tal health system for informing county health sector decision making. We conducted an initial assessment of state of mental health systems in Kilif County and documented resources, policy and legislation and spectrum of mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Methods: This was a pilot study that used the brief version of the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instru- ment for Mental Health Systems Version 2.2 to collect data. Data collection was based on the year 2014. Results: Kilif county has two public psychiatric outpatient units that are part of general hospitals. There is no stan- dalone mental hospital in Kilif. There are no inpatients or community based facilities for people with mental health problems. Although the psychiatric facilities in Kilif have an essential drugs list, supply of drugs is erratic with frequent shortages. There is no psychiatrist or psychologist in Kilif with only two psychiatric nurses for a population of approxi- mately 1.2 million people. -

Sediment Dynamics and Improvised Control Technologies in the Athi River Drainage Basin, Kenya

Sediment Dynamics in Changing Environments (Proceedings of a symposium held 485 in Christchurch, New Zealand, December 2008). IAHS Publ. 325, 2008. Sediment dynamics and improvised control technologies in the Athi River drainage basin, Kenya SHADRACK MULEI KITHIIA Postgraduate Programme in Hydrology, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Nairobi, PO Box 30197, 00100 GPO, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] Abstract In Kenya, the changing of land-use systems from the more traditional systems of the 1960s to the present mechanized status, contributes enormous amounts of sediments due to water inundations. The Athi River drains areas that are subject to intense agricultural, industrial, commercial and population settlement activities. These activities contribute immensely to the processes of soil erosion and sediment transport, a phenomenon more pronounced in the middle and lower reaches of the river where the soils are much more fragile and the river tributaries are seasonal in nature. Total Suspended Sediments (TSS) equivalent to sediment fluxes of 13 457, 131 089 and 2 057 487 t year-1 were recorded in the headwater areas, middle and lower reaches of the river, respectively. These varying trends in sediment transport and amount are mainly due to the chemical composition of the soil coupled with the land-soil conservation measures already in practice, and which started in the 1930s and reached their peak in the early 1980s. This paper examines trends in soil erosion and sediment transport dynamics progressively downstream. The land-use activities and soil conservation, control and management technologies, which focus on minimizing the impacts of overland flow, are examined to assess the economic and environmental sustainability of these areas, communal societal benefits and the country in general. -

The Water Crisis in Kenya: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

Global Majority E-Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1 (June 2011), pp. 31-45 The Water Crisis in Kenya: Causes, Effects and Solutions Samantha Marshall Abstract Located on the eastern coast of Africa, Kenya, a generally dry country with a humid climate, is enduring a severe water crisis. Several issues such as global warming (causing recurrent and increasingly severe droughts as well as floods), the contamination of drinking water, and a lack of investment in water resources have enhanced the crisis. This article provides an overview of Kenya’s water crisis, along with a brief review of the literature and some empirical background. It reviews the main causes of the water crisis and how it affects the health of millions of Kenyans. Furthermore, the article summarizes some of the main solutions proposed to overcome the crisis. I. Introduction There are about 40 million people living in Kenya, of which about 17 million (43 percent) do not have access to clean water.1 For decades, water scarcity has been a major issue in Kenya, caused mainly by years of recurrent droughts, poor management of water supply, contamination of the available water, and a sharp increase in water demand resulting from relatively high population growth. The lack of rainfall affects also the ability to acquire food and has led to eruptions of violence in Kenya. In many areas, the shortage of water in Kenya has been amplified by the government’s lack of investment in water, especially in rural areas. Most of the urban poor Kenyans only have access to polluted water, which has caused cholera epidemics and multiple other diseases that affect health and livelihoods. -

469880Esw0whit10cities0rep

Report No. 46988 Public Disclosure Authorized &,7,(62)+23(" GOVERNANCE, ECONOMIC AND HUMAN CHALLENGES OF KENYA’S FIVE LARGEST CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized December 2008 Water and Urban Unit 1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank __________________________ This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without written authorization from the World Bank. ii PREFACE The objective of this sector work is to fill existing gaps in the knowledge of Kenya’s five largest cities, to provide data and analysis that will help inform the evolving urban agenda in Kenya, and to provide inputs into the preparation of the Kenya Municipal Program (KMP). This overview report is first report among a set of six reports comprising of the overview report and five city-specific reports for Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Nakuru and Eldoret. The study was undertaken by a team comprising of Balakrishnan Menon Parameswaran (Team Leader, World Bank); James Mutero (Consultant Team Leader), Simon Macharia, Margaret Ng’ayu, Makheti Barasa and Susan Kagondu (Consultants). Matthew Glasser, Sumila Gulyani, James Karuiru, Carolyn Winter, Zara Inga Sarzin and Judy Baker (World Bank) provided support and feedback during the entire course of work. The work was undertaken collaboratively with UN Habitat, represented by David Kithkaye and Kerstin Sommers in Nairobi. The team worked under the guidance of Colin Bruce (Country Director, Kenya) and Jamie Biderman (Sector Manager, AFTU1). The team also wishes to thank Abha Joshi-Ghani (Sector Manager, FEU-Urban), Junaid Kamal Ahmad (Sector Manager, SASDU), Mila Freire (Sr. -

Flash Update

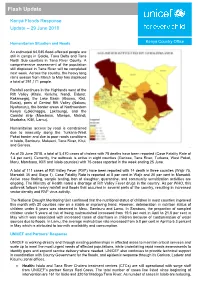

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of May 2021 marks the cessation of the Long- Rains over most parts of the country except for the western and Coastal regions according to Kenya Metrological Department. During the month of May 2021, most ASAL counties received over 70 percent of average rainfall except Wajir, Garissa, Kilifi, Lamu, Kwale, Taita Taveta and Tana River that received between 25-50 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of May as shown in Figure 1. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1 indicates rainfall performance during the month of May as Figure 1.May Rainfall Performance percentage of long term mean(LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Metrological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of June 2021. Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to be sunny and dry with occasional rainfall expected from the third week of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for June. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall that is expected throughout the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be below the long-term average amounts for June. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional cool and cloudy Figure 2.Rainfall forecast (overcast skies) conditions with occasional light morning rains/drizzles. -

Kenya – Malindi Integrated Social Health Development Programme - Mishdp

Ufficio IX DGCS Valutazione KENYA – MALINDI INTEGRATED SOCIAL HEALTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME - MISHDP INSERIRE UNA FOTOGRAFIA RAPPRESENTATIVA DEL PROGETTO August 2012 Evaluation Evalutation of the “Kenya – Development integrated Programme” Initiative DRN Key data of the Project Project title Malindi–Ngomeni Integrated Development Programme Project number AID N. 2353 Estimated starting and May 2006 /April 2008 finishing dates Actual starting and May 2006 / December 2012 finishing dates Estimated Duration 24 months Actual duration 80 months due to the delays in the approval of the Programme Bilateral Agreement, allocation of funds, and delays in the activities implementation. Donor Italian Government DGCD unit administrator Technical representative in charge of the Programme: Dr Vincenzo Racalbuto Technical Area Integrated development Counterparts Coast Development Authority (CDA) Geographical area Kenya, Coastal area, Malindi and Magarin districts*, with particular attention to the Ngonemi area During the planning and the start of the project, Magarini district was part of the Malindi district, in the initial reports, in fact, Magarini is referred to as Magarini Division of the Malindi District. Since the mid 2011 the Magarini Division becomes a District on its own Financial estimates Art. 15 Law 49/87 € 2.607.461 Managed directly € 487.000 Expert fund € 300.000 Local fund € 187.000 TOTALE € 3.094.461 KEY DATA OF THE EVALUATION Type of evaluation Ongoing evaluation Starting and Finishing dates of the June-August 2012 evaluation mission Members of the Evaluation Team Marco Palmini (chief of the mission) Camilla Valmarana Rapporto finale Agosto 2012 Pagina ii Evalutation of the “Kenya – Development integrated Programme” Initiative DRN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Malindi Integrated Social Health Development Programme (MISHDP) has been funded by a grant of the DGCD, according to article 15 of the Regulation of the Law 49/87, for an amount of € 2.607.461, in addition to € 487.000 allocated to the direct management component. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M.