EU Rules for Organic Wine Production Background, Evaluation and Further Sector Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasmopara Viticola Berkeley Et Curtis)

441 Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 26 (No 2) 2020, 441–444 Resistance of hybrid wine grape breeding forms to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola Berkeley et Curtis) Iliana Ivanova*, Ralitsa Mincheva, Galina Dyakova, Gergana Ivanova-Kovacheva Institute of Agriculture and Seed Science “Obraztsov Chiflik” – Rousse, Rousse 7007, Bulgaria *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Ivanova, I., Mincheva, R., Dyakova, G., & Ivanova-Kovacheva, G. (2020). Resistance of hybrid wine grape breed- ing forms to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola Berkeley et Curtis). Bulg. J. of Agric. Sci., 26(2), 441–444 In the period 2014-2016, at the experimental vineyard of the Institute of Agriculture and Seed Science “Obraztsov Chiflik” – Rousse, the resistance of hybrid wine grape breeding forms to downy mildew with causative agent Plasmopara viticola (Berkeley et Curtis) oomycetes fungus was studied. Objects of the study were the hybrids: 25/12 (Pamid Rousse 1 × Kaylash- ki Misket), 5/51 (Naslada × Chardonnay) and 5/83 (Naslada x Chardonnay). Misket Otonel cultivar was chosen as control. The aim was the reaction of hybrid wine breeding forms of vine to downy mildew caused by Plasmopara viticola (Berkeley et Curtis) to be determined. The phytopathological assessment of the attack of Plasmopara viticola on leaves was carried out according to the OIV 452 scale, and on berries and clusters – according to the OIV 453 scale, where the resistance was represented in 5 grades 1-3-5-7-9, as 1 was maximum resistance. The following traits were registered: index of attack (%), correlation coefficient between disease progression and yield obtained, weight of cluster (kg), maturation period, sugar content (%), acid content (g/l). -

Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking

fermentation Article Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking Chun Tang Feng, Xue Du and Josephine Wee * Department of Food Science, The Pennsylvania State University, Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Building, State College, PA 16803, USA; [email protected] (C.T.F.); [email protected] (X.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-814-863-2956 Abstract: Native microorganisms present on grapes can influence final wine quality. Chambourcin is the most abundant hybrid grape grown in Pennsylvania and is more resistant to cold temperatures and fungal diseases compared to Vitis vinifera. Here, non-Saccharomyces yeasts were isolated from spontaneously fermenting Chambourcin must from three regional vineyards. Using cultured-based methods and ITS sequencing, Hanseniaspora and Pichia spp. were the most dominant genus out of 29 fungal species identified. Five strains of Hanseniaspora uvarum, H. opuntiae, Pichia kluyveri, P. kudriavzevii, and Aureobasidium pullulans were characterized for the ability to tolerate sulfite and ethanol. Hanseniaspora opuntiae PSWCC64 and P. kudriavzevii PSWCC102 can tolerate 8–10% ethanol and were able to utilize 60–80% sugars during fermentation. Laboratory scale fermentations of candidate strain into sterile Chambourcin juice allowed for analyzing compounds associated with wine flavor. Nine nonvolatile compounds were conserved in inoculated fermentations. In contrast, Hanseniaspora strains PSWCC64 and PSWCC70 were positively correlated with 2-heptanol and ionone associated to fruity and floral odor and P. kudriazevii PSWCC102 was positively correlated with a Citation: Feng, C.T.; Du, X.; Wee, J. Microbial and Chemical Analysis of group of esters and acetals associated to fruity and herbaceous aroma. -

45. REASONS for WINE TOURISM in BULGARIA M. Pereviazko, K.O

45. REASONS FOR WINE TOURISM IN BULGARIA M. Pereviazko, K.O. Veres National University of Food Technologies Wine tourism industry in Western Europe, especially in France and Italy are much more developed than in Bulgaria. But this is not due to the quality of drinks. Geographically, Bulgaria is located in the same climate zone as Spain, France and Italy - the major wine regions of the world. Just like these countries, It is considered one of the centers of cultivation of grapes. Scientists believe that the Thracians in the territory of modern Bulgaria made first wine in Europe. Eater the Greeks to find out from the Thracians secret receipt of grapes divine drink and arrogated to themselves the right of the pioneers of winemaking. Why do people prefer wine tourism not just drink wine at home what bought in the store? First of all, people should be remembered that wine, as opposed to people do not like to travel. As experts consider, in a way it can "get sick." So before the 93 entertain friends by wine from faraway countries, give him a chance to "rest" at least a week. The beauty of wine tourism is not sightseeing. Meeting people who produce this drink it is remains in the memory. Real manufacturer is in love with his work, and talk with them is very interesting. Some aesthetes prefer to stay in the castles of winemakers, to communicate with these eminent people. Observation of the production of wine can cause at least surprising in an untrained person. Guests can still see how the grapes are crushed underfoot in small wineries in Bulgaria. -

Big, Bold Red Wines Aromatic White Wines Full-Bodied

“ A meal without wine is like a day without sunshine." WINE LIST - Brillat-Savarin At the CANal RITZ, we believe that wine should be accessible, affordable and enjoyable. This diverse selection of wines has been carefully designed to complement our menu and enhance your dining experience. Fresh, Lively Red Wines Available CHEERS! S A N T É! S A LU T E! in a Pinot Noir 2017, Blanville. Languedoc, France Generous fruit and spice notes. Glass, a Rioja 2017 Cosecha, Pecina. Spain ½ Litre Fresh, juicy and unoaked Tempranillo. bottle Gamay 2018, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) and a A delicious and oh so drinkable Ontario wine Full Bottle Medium-Bodied Red Wines Syrah 2017, Camas. France (organic) Light, Dry White Wines A delicious organic wine from the Limoux region in the Pinot Grigio 2018, Giusti. Veneto, Italy South of France. Refreshingly crisp with zesty citrus and mango flavours. Sangiovese 2016, Dardo. Tuscany, Italy Riesling 2017, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) Juicy red berry fruit, soft and silky on the palate, plush Dry as a bone and delicious, from one of Ontario’s tannins and flavourful. leading wineries. Chianti 2016, Lanciola. Tuscany, Italy Pinot Grigio 2017, Fidora. Veneto, Italy (organic) Made with dried grapes, this “Ripasso” style wine has This certified organic wine is refreshing with a distinct plenty of ripe fruit. minerality and crisp lemon and pear finish Frappato 2016, Vino Lauria. Sicily, Italy (organic) This deliciously atypical Sicilian wine is livelier than most wines from this hot island. Aromatic White Wines Sauvignon Blanc 2018, Middle Earth. New Zealand Rosso di Montalcino 2016, Fanti. -

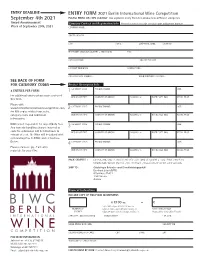

BIWC Entryform-2021-2021-7-2 Copy

ENTRY DEADLINE ENTRY FORM 2021 Berlin International Wine Competition September 4th 2021 PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE CLEARLY Use separate entry form for products in different categories Award Announcement Company Contact and Registration Info Please be sure to include contact name and phone number Week of September 20th, 2021 COMPANY NAME: STREET ADDRESS: CITY: STATE: ZIP/POSTAL CODE: COUNTRY: TELEPHONE: (INCLUDE COUNTRY + AREA CODE) FAX: CONTACT NAME: TITLE OR POSITION: CONTACT TELEPHONE: CONTACT CELL: CONTACT EMAIL ADDRESS: MAIN CORPORATE WEBSITE: SEE BACK OF FORM FOR CATEGORY CODES Product Description Info CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: 4 ENTRIES PER FORM 1 For additional entries please make copies of REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE this form. Please visit: www.berlininternationalwinecompetition.com 2 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: for PDF copies of this form, rules, category codes and additional REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE information. BIWC is not responsible for import/duty fees. CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Any material handling charges incurred as 3 costs for submission will be billed back to REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE entrant at cost. No Wine will be judged with outstanding fees to BIWC and or Customs Broker. 4 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Please retain a copy of all entry materials for your files. REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE PACK SAMPLES : (3) 750, 700, 500, or 333ml bottles for each entry along with a copy of this entry form. -

Bulgaria's Evolving Wine Market Presents New Opportunities Bulgaria

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 1/19/2018 GAIN Report Number: BU1810 Bulgaria Post: Sofia Bulgaria’s Evolving Wine Market Presents New Opportunities Report Categories: Wine Approved By: Jonn Slette Prepared By: Mila Boshnakova Report Highlights: Post forecasts Bulgaria’s 2017 grape crop at 250,000 metric tons (MT), most of which will be used to produce about 140 million liters of commercial wine. The Bulgarian wine sector continues to evolve, driven by investments in the sector, increasing disposable incomes, tourism, and thriving retail and hotel, restaurant, and catering (HORECA) sectors. Wine consumption increased in 2016 and consumer trends point to a growing preference for higher- quality wines. January-October 2017 data indicate a 24-percent increase in wine imports by volume and 21 percent by value. Poland, Sweden, China, and Russia were the top export markets for Bulgarian wine (value terms) in 2016 and in 2017. General Information: PRODUCTION FAS Sofia estimates that Bulgaria’s 2017 grape harvest will reach 250,000 MT, of which about 210,000 MT will be processed into 140 million liters of commercial wine. Other estimates predict that grape production will reach 350,000 MT and 150 million liters of commercial wine. At the end of November 2017 (source: Ministry of Agriculture (MinAg) Weekly Bulletin #49), harvest reports estimated 47,800 hectares (HA) yielded 238,000 MT of grapes, with an average yield of about 5.0 MT/HA. Weather during the year was mixed. -

Italian Market of Organic Wine: a Survey on Production System Characteristics and Marketing Strategies

Italian market of organic wine: a survey on production system characteristics and marketing strategies Alessandra Castellini*, Christine Mauracher**, Isabella Procidano** and Giovanna Sacchi** * Dept. of Agricultural Sciences DipSA, Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna [email protected] ** Dept. of Management, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice [email protected] Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the 140th EAAE Seminar, “Theories and Empirical Applications on Policy and Governance of Agri-food Value Chains,” Perugia, Italy, December 13-15, 2013 Copyright 2013 by [authors]. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. 1 1. Introduction Wine is commonly recognised as a particular type of processed agrifood product, showing several different characteristics. Above all a close relationship is commonly assigned between wine and land of origin, the environment and the ecosystem in general (including not only natural aspects but also human skills, tradition, etc.), based on a complex web of interrelation between all the involved elements/operators. Since the 70s the interest on “clean wine-growing” has been increasing among the operators; this fact has also caused the development and the improving of organic processes for wine production (Iordachescu et al., 2009). For long time the legislation framework on the organic wine regulations has been incomplete and inefficient: EC Reg. 2092/911 and, after this, EC Reg. 834/20072 were extremely generic and through these Regulations it has been only possible to certify as “organic” the raw material (grapes from organically growing technique) and not the whole wine-making process. -

Labeling Organic Wine

LABELING ORGANIC WINE All organic alcohol beverages must meet both Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and USDA organic regulations. TTB requires that alcohol beverage labels be reviewed through the Certificate of Label Approval (COLA) application process. Learn more at http://www.ttb.gov/wine. Organic-specific labeling requirements will be described in the subsequent pages. Required Elements of a Wine Label 1 Brand name 5 Bottler’s name and address 2 Class/type (such as red wine or grape varietal) 6 Net contents 3 Alcohol content 7 Sulfite declaration 4 Appellation (required in most cases). 8 Health warning statement For specific requirements related to each of these elements, other requirements, and information on labeling imported products, visit www.ttb.gov. 3 HOSIS ORP AM ET del M f an ALC. 12% BY VOL. 12% BY ALC. n zi 07 20 delic ately b dness alancing bol . xture with nuance and te y S e MORPHO I n y META SIS r ttled b u + bo S uced o prod ornia j 5 calif O r ma, u ono H yo s P e 1 R id 7 gu O o M s t CONTAINS ONLY NATURALLY M E T A ne OCCURRING SULFITES. wi gutsy Certied organic by ABC Certiers 8 2 GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) ACCORDING TO THE SURGEON GENERAL, WOMEN SHOULD NOT DRINK el ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES DURING PREGNANCY BECAUSE fa nd zin OF THE RISK OF BIRTH DEFECTS. (2) CONSUMPTION OF 07 unty, californi ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES IMPAIRS YOUR ABILITY TO 20 ma co a 4 ono DRIVE A CAR OR OPERATE MACHINERY, AND MAY s CAUSE HEALTH PROBLEMS. -

European Union

University of Craiova BalkanCOALIȚIA Civic CoalitionCIVICĂ PENTRU BALCANI Romanian Association for Technology Transfer and Innovation (A.R.o.T.T.) Adress: 12 Stefan cel Mare street, 200130, Craiova, Person of contact: Gabriel Vlăduţ Tel: +40 251 412 290; Fax: +4 0251 418 882; E-mail: [email protected]; www.arott.ro Investing in your future! Romania-Bulgaria Cross Border Cooperation Programme 2007-2013 is co-financedby the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund. Project title: „Wine Way“ Editor of the material: ARoTT Date of publishing: dd noiembrie 2012 The content of this material does not necessarily represent the official position of the European Union. www.cbcromaniabulgaria.eu EUROPEAN UNION Innovation, Technology Transfer EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND GOVERNMENT OF ROMANIA GOVERNMENT OF BULGARIA Wine Way Cross Border Cooperation Programme Common borders. Common solutions. WINE WAY Contents Table of Contents ..........................................................3 Corcova Roy & Damboviceanu ...........................................5 Research and Development Station for Plant Growing on Dabuleni Sand ...................................6 “The Crown Estate” Wine-Cellar of Segarcea ........................8 “Banu Mărăcine” Research Station .....................................9 Viti-Pomicola Samburesti SA – Samburesti Estates ................ 10 Vinarte Estates ........................................................... 12 Vine-Wine Segarcea ..................................................... 13 Cetate -

Return to Terroir

RETURN TO TERROIR “Biodynamy, wine growing for the future” TASTING Is biodynamic Wine-growing a Myth or a Realit y? By Nicolas Joly – Coulée de Serrant There is no doubt that more and more fascinated private individuals and professionals are discovering a source of complexity, a surge of vitality, and an additional purity in the increasing number of biodynamic wines. There is also no doubt that this type of agriculture, which differs from biological agriculture insofar as it adds very small amounts of preparations per hectares, quantities varying from one to one hundred grams, that have usually been dynamised in water, can upset those who try to understand it. How can such small quantities have any real effect on the quality of wine? Wouldn’t the result be the same with simple biological agriculture? Faced with these questions, the group of those in favour and those against puff themselves up by publicly making boasts on a regular basis, as behind the scenes both sides prepare for battle. In order to pass from the profound convictions which generate belief to knowledge and thus a more rigorous demonstration, there is finally a step to be taken here. It is on this approach that partially depends the authenticity of the quality of our future wines. Let us begin by observing the corpse of an animal that has just died. In a few weeks its simple elements will again be part of the earth. Thus the question to ask is: where are the energies which constructed this organism in such a sophisticated manner? Who took the calcium to sculpt the bone? Who took the silica to form the hair? Don’t these forces exist in other ways besides forming embryos? A seed, an egg. -

Natural, Organic & Biodynamic Wine

Natural, Organic & Biodynamic Wine “NATURAL” Wine: • General, broad reference to wines made in low-tech, non-interventionist style, e.g…. o Low or no use of chemicals in vineyard o Native yeasts used in fermentation o Low or no use of sulfur in winery o No chemical or technical “adjustments” to the final wine • Technically, zero regulations about what can/can’t be declared “natural” “ORGANIC” Wine: • Organic defined by USDA National Organic Program (NOP) as a product that uses no pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, genetically modified organisms, or ionizing radiation • To be labeled as organic in US, must be inspected and approved by USDA • TTB, USDA and NOP labeling laws for wines sold in the US: o Organic: at least 95% organically produced ingredients and NO added sulfur allowed (or less than 10 ppm) o 100% Organic: 100% organically produced ingredients and NO added sulfur allowed (or less than 10 ppm) § Additional approved labeling: USDA Organic seal; “Certified Organic by ____” o Made from organic grapes: MUST note “contains sulfites” § Is it a problem if “made from organic grapes” can also include up to 30% non- organic grapes or “other ingredients”? § Is it a problem if many wines are made entirely organically yet with sulfur and so can’t be labeled organic when sold in US? § In the EU, wines with up to 100 ppm of sulfites can be labeled organic “BIODYNAMIC” Wine: • Biodynamic agriculture is a sustainable system proposed by Rudolf Steiner that involves using natural preparations in the field and following the lunar calendar for viticulture/vinification steps o Natural preparations are all organic, herb-, root- or animal-based products o Lunar calendar suggests fruit/flower/root/leaf days corresponding to certain tasks such as picking, pruning, racking, bottling • Many producers practice biodynamics but are not certified (expensive process) • Major certifying body is Demeter; certified wines can carry seal on their label All class outlines are copyright of Corkbuzz Wine Studio. -

The Need for Cooperation and Collaboration in the Spanish Natural Wine Industry

Vol. 3, No. 1 FINDING COMMON GROUND: THE NEED FOR COOPERATION AND COLLABORATION IN THE SPANISH NATURAL WINE INDUSTRY Rosana Fuentes Fernández, Campus Universitario Villanueva de Gállego, Spain INTRODUCTION atural wines represented an emerging wine segment that appeared to be growing in popularity among the Generation Y (Millennials) and Generation Z, demographic N groups that tended to be health and environmentally conscious consumers. Natural wines were loosely defined as those made from grapes grown by small, independent farms and harvested by hand from sustainable, organic, or biodynamic vineyards. These wines typically contained no additives or sulfites, and therefore were believed to be a healthier alternative to their mass-produced counterparts. For growers and producers, natural wine was a philosophy, a way of life, a route “chosen out of conviction and a desire to nurture the most fundamental force of all—Life” (Legeron, 2017: 95). Traditional wine-making techniques (pre-WWII) were a time-honored and essential part of what makes a wine “natural.” Many of these wine-making techniques were passed down from generation to generation. Additionally, the vineyards themselves tended to have very old vines. As such, the European Union (EU) appeared to be on the forefront of producing natural wines since many small, traditional wine businesses were located there. Wine consumption trends showed that consumers were increasingly drinking less wine, but at the same time were more health conscious, and this philosophy was impacting their purchasing decisions (IWSR, 2019; Sorvino, 2019). This was a significant trend for the natural wine segment. However, natural wine producers faced many challenges: limited resources, geographic isolation, lack of consumer education, and difficult growing conditions.